Introduction↑

One of the hallmarks of the Great War was the high number of military and civilian casualties it caused. Over more than four years of fighting between nearly two dozen countries, it is estimated that 8.5 million men died, about 21 million were injured, and 7.7 million went missing or were captured.[1]

The task of ascertaining the precise number of casualties is difficult not only because of the high number involved, but also due to the absence or deficiency of the necessary documentary records. On the other hand, political or military interests must be taken into account, since they may have resulted in overvaluing or underestimating losses suffered. Consequently, the figures presented may be inflated or deflated, depending on the case, for example for propaganda purposes or when discussing war reparation amounts. The use of different criteria in counting victims also tends to produce different results.

Framework↑

In the Portuguese case, the number of victims was much lower than in other belligerent countries, although it left a heavy mark at a national level. The size of the mobilized contingent, the late entry into war (9 March 1916) and the peripheral location of the country, far from the main and deadly battlefields, explain this fact. However, when comparing Portuguese casualties (36 percent) with those of other nationalities in percentage terms in relation to the total mobilized, it becomes clear that the toll was heavier than, for example, Bulgarian (22.2 percent), Greek (11.7 percent), Japanese (0.2 percent) or even American (8.2 percent) losses.[2]

The Portuguese losses are also characterized by the fact that they occurred in several operational theaters[3] located on two continents (Europe and Africa) and in different campaigns (against the Germans and the indigenous people of Africa in rebellion). Casualties began before Portugal's official entry into the war[4] and they resulted from the classic trench war fought on the Western Front as well from the unique, elusive and innovative subversive war of movement led by Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck (1870-1964), the German commander who fought the Allies in German East Africa and Mozambique. Other casualties were inflicted by German attacks, far from the frontline, against ports, cities and ships in the Atlantic. German submarines attacked ships in the ports of Funchal, Ponta Delgada and the island of São Vicente in Cape Verde, causing the loss of human lives and material damages through sinking ships and bombing buildings on land. The most deadly attack took place in Funchal on 3 December 1916. Three ships were sunk and forty people were killed, most of them French sailors.

To these civilians one must add the casualties among the indigenous population of the Portuguese colonial territories, namely in southern Angola and above all in northern Mozambique, where the war started earlier than in Europe (the Portuguese participation in France began only in 1917, but the fighting with the Germans in Africa began in 1914) and where it may have caused between 35,000 and 105,000 casualties (dead and missing).[5] These figures are only estimates. Many analysts consider the latter figure excessive, inflated by the Portuguese government to substantiate the claim for reparations by Germany in the post-war period. The lack of adequate censuses and the fluid circulation of the native peoples among the various colonial territories also contributed to these inaccurate estimates.[6] In fact, this strict clarification, even in relation to exclusive military human losses, has never been an easy task and different numbers have been presented over the decades following the end of the conflict.

However, some facts are absolutely consensual and commonly accepted. More Portuguese soldiers and their auxiliaries died in Africa, particularly in Mozambique, than in Europe. Furthermore, these deaths were mostly caused by endemic diseases (such as dysentery, malaria, fevers and anemia) and not from fighting against the Germans and the rebellious indigenous populations. Such casualties were largely the result of the improvisation observed both in the preparation of troops and in the conduct of military operations in territories with an adverse terrain and climate, almost devoid of the resources and means of communication that could sustain the forces in large-scale operations.

Along the Western Front the situation was reversed. Deaths occurred mostly in combat in the frontline trenches, as a result of the immobility of the armies and the enormous intensity of the encounters provoked by the use of weapons with great lethal capacity. It was in France that most of the Portuguese army’s injuries and disabilities were incurred, mainly due to the use of intensive firepower against static positions, the confinement of men to small spaces, and the use of poison gas. It was also the case that many men who were suffering serious illnesses at the time of their recruitment were nevertheless accepted into military service and dispatched to France. Those who died of disease were mainly victims of tuberculosis, bronchopneumonia, pneumonia and influenza.

Finally, the number of missing servicemen was highest in Mozambique and resulted from the vastness of the inhospitable territories, where the marches and counter-marches of the campaigning forces took place, as well as the high number of indigenous troops and porters used and the long duration of the campaign.

But what, in fact, were Portugal’s human losses?

The Numbers↑

Deaths↑

In the case of Portuguese soldiers in France, the first number advanced, in 1919, was a minimum of 1,601 deaths. Later, in 1924, a maximum figure of 2,288 deaths was presented. Subsequently, in the 1930s, this number was reduced to between 2,086 and 2,090 deaths.[7] For Africa, there was always greater stability in reported numbers. In Angola, 810 deaths were almost always reported, except in one case. In an undated source, 885 deaths are indicated.[8] In Mozambique, most sources and authors reported 4,811 deaths, sometimes rounded down to 4,800. There is, however, a case where a lower number (4,723) is indicated, precisely by the same source that reported the lowest number of deaths in France, just after the end of the war.[9] Still another case, the aforementioned undated source, gives a slightly higher number (4,847). Altogether, 5,533 to 5,732 men died in Africa, according to these sources and authors.

The mortal casualties suffered by the navy are rarely mentioned and when they are, the number referred to is unanimous: 142 deaths.[10]

Data made available online from April 2014 on the virtual Memorial to the Fallen in the Great War,[11] which was collected from various documentary sources and compiled in different archives, has helped to provide a more rigorous determination of Portuguese casualties, allowing for a more precise determination of who died. Some information is given as well for each mortal casualty. Thus, unlike the previously collected data, which was of a purely statistical nature, concrete and more detailed elements are now available. On the virtual memorial, each number corresponds to an individual whose identity is known.

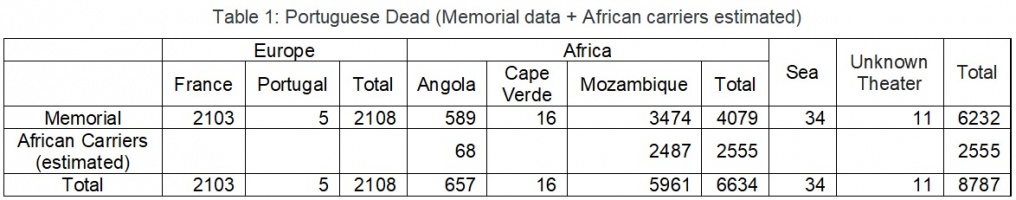

At least 6,232 Portuguese died, including European and indigenous military personnel and civilians in the service of the armed forces (see the table "Portuguese war losses"). 2,101 died in France, 568 in Angola, six in Cape Verde, and 3,345 in Mozambique in the service of the army, the air corps and various other militarized corps. 209 navy personnel also died aboard ships and on land.[12] However, counting the navy, considering the operational theaters in which its men served and died, the final figures are: 2,103 in France, 589 in Angola, sixteen in Cape Verde, thirty-four at sea, 3,474 in Mozambique, five in Portugal and eleven whose theater of operations is unknown. Finally, if the estimates of deceased native carriers (sixty-eight Angolans and 2,487 Mozambicans)[13] not mentioned on the virtual memorial are added to these confirmed values – which only accounts for those deaths for which there is identification – then we estimate that 8,787 Portuguese died (6,232 confirmed and 2,555 estimated), distributed as follows: 2,103 in France, 657 in Angola, sixteen in Cape Verde, thirty-four at sea, 5,961 in Mozambique, five in Portugal and eleven whose theater of operations is unknown.

Such a calculation does not include the civilian victims of the German bombardments of Funchal (Madeira) and Ponta Delgada (Azores), the sinking of merchant ships by submarines, and the 35,000 to 105,000 casualties among the indigenous population of Angola and Mozambique. Because they are based on uncertain estimates, subject to discussion and making little distinction between killed and missing, these have not been taken into account.

According to the information contained in the virtual memorial, the dead are almost all privates and similar ranks (91.5 percent). Most of them served in the infantry (about 75 percent) and half of them (50.1 percent) died in a single year: 1918. It should also be noted that half of the deaths in Mozambique (50.8 percent) occurred between the beginning of the second half of 1917 and the end of the first half of 1918. The individuals who died were mostly of European origin (77.6 percent) and, mainly from the north (45.3 percent) and center (42.5 percent) of Portugal. By district, the three most affected were Oporto (17.5 percent), Braga (11.8 percent) and Coimbra (7.2 percent), losing 844, 572 and 348 men respectively. As far as municipalities are concerned, three of them exceeded 100 dead. Porto, once again, was by far the most affected with 238 deaths; it was followed by Lisbon (156) and Santo Tirso (110).[14]

Wounded and Missing↑

With regard to the wounded and missing, there is no consensus as to their actual number. For the former, the values put forward range from 5,800 to 7,700 individuals, because different sources do not always indicate data for all theaters of operations; in addition, they do not always count navy personnel, thus making it impossible to compare correctly and giving rise to greater discrepancies than those that actually exist.

In 1919, an estimate of 5,219 wounded soldiers was produced in France. This figure rose slightly in the following year to 5,244. Much later calculations indicate more than 5,300 wounded, reaching a maximum of 5,359. In Angola, the first estimates pointed to 311 wounded, while more recent authors refer to 683, adding to the wounded, certainly by mistake, the military personnel unfit for service (372), whose incapacity need not have arisen in combat. The same situation seems to occur in Mozambique. The wounded initially estimated were 301, while the most recent authors refer to 1,584 or 1,600. If one takes into account that the total number the military considered unfit for service was 1,283, as is mentioned by these authors, one can assume that there was an “error” in the accounting, since the sum of both values (301 and 1,283) yields precisely 1,584 individuals. Mere coincidence? One cannot know for sure since, as is true in the case of mortal victims, there is no systematic, nominative and credible survey identical to that provided by the virtual Memorial to the Fallen in the Great War. Thus, between 600 and 2,300 soldiers can be said to have been wounded in Africa. Finally, thirty wounded navy personnel must be added to the army figures.[15]

With regard to the missing soldiers (those whose whereabouts were unknown, presumed dead), the uncertainty as to their real numbers is evident, once again, in the values found in diverse sources and authors. These range from 5,600 to 5,900 individuals. However, in this case there may be an inflation of values, for the simple reason that the overwhelming majority of the disappeared (5,467) are Mozambican natives who worked as carriers. Their forced recruitment, the ill-treatment to which they were subjected, their removal from their families, their detachment from a war they did not understand and which was not theirs, as well as the fear of being wounded or killed, are more than sufficient reasons to advance the possibility that a good part of these disappearances corresponded not to deaths, but to acts of desertion. Whenever Mozambican carriers had the chance to flee, they took advantage of it, returning to their homes. It should not be forgotten that most of the disappearances, as previously mentioned, occurred in Mozambique, where the war was intense and long. This required the employment of large numbers of carriers, whose total number could amount to 60,000 men.[16] In fact, among the missing soldiers in Mozambique, only nine were Europeans.[17]

In France, 191 Portuguese soldiers were reported as missing in 1937, when the List of Portuguese Deaths in the Great War in Germany, Belgium, France, and the Netherlands was published by the Foreign War Graves Service of the Ministry of War. However, their initial number in 1919 was 499, falling in the following year to 147, then rising to 222 in 1932, and falling back to 199 in 1933.[18]

In the list of casualties are also included the aforementioned disabled soldiers who, by decision of the health boards, were judged to be unfit, totally or partially, for military service, as a result of injuries received or otherwise. Mutilated soldiers are also included, whose physical deficiencies acquired in combat or by accident accompanied them for the rest of their life, incapacitating them or, at least, leading to their return home and the resumption of the life they led before the war. In the case of Portuguese soldiers in France, the figures for the disabled are very detailed and, although there is some divergence of values, it is slight and understandable. It was first advanced in 1919 as 7,223 and reached, according to the most recent estimates, a total of 7,280 military personnel. Of these, 5,738 (78.8 percent) were considered incapable of any service, to whom the highest degree of disability was attributed, permanently removing them from the ranks. The second largest portion is made up of those who are at the extreme opposite, that is, those who despite some degree of incapacity (the smallest), were nevertheless assigned to ancillary services. They are 1,008 and correspond to 13.8 percent of the total of the disabled.

Between the two extremes, from the highest to the lowest degree of physical disability, are included those deemed unfit for active service (404) and the 119 deemed unfit for service in the Portuguese Expeditionary Corps. In addition, one must also consider eleven military personnel for recovery as mutilated.[19]

The number of incapacitated soldiers in Angola ranges from 252 to 372. The latter figure, which was produced in 1920, became consensual. A large majority (354, corresponding to 95.1 percent) was composed of indigenous personnel. However, little is known about the different degrees and causes of the registered disability. The same is true for Mozambique, where the majority of those deemed unfit were also indigenous: 1,248 (97.3 percent). No other numbers are recorded in the different sources and authors, there being, therefore, absolute consensus. Finally, the mutilated or invalids of war are estimated at 1,579 men for all theaters of operations.[20]

Conclusion↑

This article sought to contribute to a better understanding of Portuguese war losses in the Great War, both in Europe and in Africa, namely with regard to their quantification. It does not intend to impose absolute numbers. Based on the virtual Memorial to the Fallen in the Great War – the most recent inventory, based on official sources – the article tried to estimate, not determine, a number of fatalities, as close as possible to reality.

A minimum of 6,232 Portuguese died, including European and indigenous military personnel and civilians in the service of the armed forces, but we estimated that 8,787 Portuguese died (6,232 confirmed and 2,555 estimated). With regard to the wounded and missing, there is no consensus as to their actual number. For the former, the values put forward range from 5,800 to 7,700 individuals. With regard to the missing soldiers, uncertainty as to their real numbers is also evident between different sources and authors. These range between 5,600 to 5,900 individuals. Finally, the number of incapacitated soldiers in military service is estimated at about 8,900 individuals, and the invalids of war are estimated at 1,579 men.

In total, the number of Portuguese casualties (dead, injured, missing, incapacitated and mutilated) in the war is estimated at between 30,500 and 32,900 individuals. This number appears to be low when compared with other countries. However, it had a significant impact on Portugal, considering the total number of soldiers mobilized.

João Moreira Tavares, Universidade Nova de Lisboa

Section Editor: Filipe Ribeiro de Meneses

Notes

- ↑ Afonso, Aniceto: Grande Guerra. Angola, Moçambique e Flandres, 1914-1918 [Great War. Angola, Mozambique and Flanders, 1914-1918], Matosinhos 2006, p. 114.

- ↑ Afonso, Aniceto / Gomes, Carlos de Matos (eds.): Portugal e a Grande Guerra, 1914-1918 [Portugal and the Great War, 1914-1918], Lisbon 2003, p. 547.

- ↑ The theater (or zone) of operations is the part of a territory, of variable size, required for the accomplishment of the campaign forces’ tactical and logistic operations. The Portuguese military fought in Angola, France and Mozambique, as well as in the Azores, Cape Verde, Madeira and the Atlantic Ocean.

- ↑ Around 370 Portuguese soldiers died before Portugal’s official entry into the war.

- ↑ 5,000 in Angola and between 30,000 to 100,000 in Mozambique according to different authors.

- ↑ Oliveira, Arménio N. de (ed.): História do Exército Português (1910-1945) [History of the Portuguese Army (1910-1945)], volume 3, Lisbon 1994, p. 235.

- ↑ See Martins, Dorbalino dos Santos: Estudo de Pesquisa sobre a Intervenção Portuguesa na 1ª Guerra Mundial (1914-1918) na Flandres [Research on Portuguese Intervention in World War I (1914-1918) in Flanders], Lisbon 1995, pp. 541, 542, 543 and 549. The original maps and lists can be found in the Arquivo Histórico Militar for the years 1919 and 1933 respectively. See Arquivo Histórico Militar, Lisbon, PT AHM/DIV/1/35/1064/4 and PT AHM/DIV/1/35/1401/9. For the year 1920 there are records of losses, dated 11 and 25 March. See PT AHM/DIV/2/10/3/3.

- ↑ See Arquivo Histórico Militar, Lisbon, PT AHM/DIV/2/10/1/38.

- ↑ See Arquivo Histórico Militar, Lisbon, PT AHM/DIV/1/35/1064/4.

- ↑ See Afonso / Gomes, Portugal 2003, p. 549. Oliveira, História 1994, p. 270.

- ↑ Memorial aos Mortos na Grande Guerra. Memorial to the Fallen in the Great War, issued by Arquivo Histórico Militar, online: http://www.memorialvirtual.defesa.pt (retrieved: 26 February 2020).

- ↑ Three army soldiers without theater operations set are added to these, making up the 6,232 deceased.

- ↑ See Arquivo Histórico Militar, Lisbon, PT AHM/DIV/1/35/1064/4, PT AHM/DIV/2/10/1/38 and PT AHM/DIV/2/10/3/3. Sixty-eight Angolans are also identified as indigenous auxiliaries or even indigenous soldiers.

- ↑ Tavares, João Moreira: Os Mortos da Grande Guerra. O Caso Português [The Dead of the Great War. The Portuguese Case], in: Rocha, Jorge Silva (ed.): Actas do XXVI colóquio de história militar "Portugal 1916-1918. Da guerra à paz" (Proceedings of the XXVI Military History Conference "Portugal 1916-1918. From War to Peace"), Lisbon 2018, pp. 424-426; Tavares, João Moreira: Mortos, feridos e desaparecidos [Dead, Wounded and Missing], in: Lousada, Abílio Pires / Rocha, Jorge Silva (eds.): Portugal na 1ª Guerra Mundial. Uma história militar concisa [Portugal in the First World War. A Concise Military History], Lisbon 2018, pp. 781-787.

- ↑ Afonso / Gomes, Portugal 2003, p. 549 and Oliveira, História 1994, p. 270.

- ↑ In fact, the number of carriers amounted to 90,000, but 30,000 were awarded to British troops. Oliveira, História 1994, p. 233.

- ↑ See Arquivo Histórico Militar, Lisbon, PT AHM/DIV/2/10/3/3.

- ↑ Aniceto Afonso and Carlos Matos Gomes not only indicate 199 missing but also 234, after adding thirty-five identified to the 199 missing who are not identified. Afonso / Gomes, Portugal 2003, pp. 549, 551.

- ↑ Afonso / Gomes, Portugal 2003, p. 551.

- ↑ Correia, Silvia: Inválidos de Guerra [Invalids of War] in: Rollo, Maria Fernanda (ed.): Dicionário de História da I República e do Republicanismo. F-M [Dictionary of History of the First Republic and of Republicanism. F-M], volume 2, Lisbon 2014, p. 497; Oliveira, História 1994, p. 270.

Selected Bibliography

- Afonso, Aniceto: Grande Guerra. Angola, Moçambique e Flandres, 1914-1918 (Great War. Angola, Mozambique and Flanders, 1914-1918), Matosinhos 2008: Quidnovi.

- Afonso, Aniceto / Gomes, Carlos de Matos: Portugal e a Grande Guerra, 1914-1918 (Portugal and the Great War, 1914-1918), Matosinhos 2010: QuidNovi.

- Correia, Silvia: Inválidos de Guerra (Invalids of war), in: Rollo, Maria Fernanda (ed.): Dicionário de história da I República e do republicanismo. F-M (Dictionary of history of the First Republic and of republicanism. F-M), volume 2, Lisbon 2014: Assembleia da República, pp. 497-500.

- Martins, Dorbalino dos Santos: Estudo de pesquisa sobre a intervenção portuguesa na 1a Guerra Mundial (1914-1918) na Flandres (Research on Portuguese intervention in World War I (1914-1918) in Flanders), Lisbon 1995: Direcção de Documentação e História Militar.

- Oliveira, Arménio N. de: História do exército português, 1910-1945 (History of the Portuguese army, 1910-1945), volume 3, Lisbon 1994: Estado Maior do Exército.

- Tavares, João Moreira: Os mortos da Grande Guerra. O caso português (The dead of the Great War. The Portuguese case), in: Rocha, Jorge Silva (ed.): Actas do XXVI colóquio de história militar 'Portugal 1916-1918. Da guerra à paz' (Proceedings of the XXVI military history conference 'Portugal 1916-1918. From war to peace'), Lisbon 2018: Comissão Portuguesa de História Militar, pp. 415-433.

- Tavares, João Moreira: Mortos, feridos e desaparecidos. Um retrato das vítimas (Dead, injured and missing. A portrait of the victims), in: Jornal do Exército, 2018, pp. 68-69.

- Tavares, João Moreira: Mortos, feridos e desaparecidos (Dead, wounded and missing), in: Lousada, Abílio Pires / Rocha, Jorge Silva (eds.): Portugal na 1ª Guerra Mundial. Uma história militar concisa (Portugal in the First World War. A concise military history), Lisbon 2018: Comissão Portuguesa de História Militar, pp. 781-794.