Introduction↑

In the late 19th century, structural changes affected manufacturing work and workers’ household economies in Portugal, as in the other southern European countries. Urbanization contributed to the creation of a physical and social context that potentiated a broader sense of unity and solidarity between workers.[1] At the dawn of the 20th century, the labour movement assumed new proportions and featured new protagonists.

It was the factory proletariat that gave an unprecedented massive scale to strikes, although, particularly in late industrializing countries like Portugal, skilled workers and their organizational resources played a crucial role. Artisans' traditional organizations, inherited from the Ancien régime, adapted to the new organization of work, incorporating the demands of unskilled workers who became the majority of industrial employees. Claims related to wages in particular increased as unions tried to ensure the convergence of interests between different social strata within working-class.[2] In the beginning of the 20th century, the Portuguese labour movement became more radical in its aims and actions, aiding to create a favourable juncture for the republican revolution of 5 October 1910.[3]

The advent of the republican regime represented an attempt to modernize the political system in the face of these structural transformations but it was unable to foster a new social balance.[4] A strike was declared in December 1910, and simultaneously an employers’ lock out in a decree strongly criticized by the labour movement. Despite popular support, republican leaders responded repressively to the first massive wave of strikes (1910-1913), with the first deaths in March 1911, an event which became known as the divorce between the republic and the workers.[5]

According to the classical historian Fernando Medeiros, during Portuguese participation in the First World War, the labour movement was virtually gagged by the so-called crack trade unionist Afonso Costa (1871-1937), though this did not prevent the social unrest due to the increasing cost of living. The revolutionary syndicalists were accused of being the first instigators of public disorder and the National Workers’ Union (UON) was dissolved at the beginning of 1915. In March 1916, the government of the union sacrée established censorship of the press and postal service but tried to seduce the more moderate wing of the labour movement to support the war effort in change for social reforms carried out by the new Ministry of Labour and Social Providence.[6]

The structural imbalance in Portugal’s food supply and its deficient transport network impeded the effectiveness of interventionist policies concerning supplies, carried out by the Democratic Party or the union sacrée. The question of subsistence engaged the discontent of the working class but also of those dependent on fixed incomes and agrarian elites harmed by the war economy, which converged for the emergence of antiparliamentary and anti-liberal phenomena, such as the dictatorship of Pimenta de Castro (1915; 1846-1918) and of Sidónio Pais (1917-1918; 1872-1918).[7]

The “terrible year” of 1917, in which the strike movement was heavily repressed by the army, saw the downfall of the old republic. The military coup of Sidónio Pais had significant popular support and ushered in a new strategy regarding the social question. The Revolutionary Junta freed social prisoners and promised to negotiate with the organized labour movement, creating a temporary appeasement of the workers which would not survive another winter of hunger and epidemics.[8]

The republic’s repressive repertoire, particularly during the war, was characterized by the common suspension of constitutional guaranties. In this aspect, Sidónio Pais’ dictatorship was not a novelty. However, the new republic experimented a new type of repressive system based on army loyalty, the militarization of the civic police, and the creation of a preventive (political) police.[9]

The Winters of Our Discontent: the Struggle Against Speculation and Hoarding↑

Although there is no official data on the popular upheavals during the war, in the 1980s Carlos da Fonseca published the first and unique chronology of Portuguese social movements, including both strikes and popular upheavals.[10] Recent studies of the First World war period confirm his work.[11] Both da Fonseca’s work and more recent studies relied on the national press as the main primary source.

According to these surveys, the protests and riots, with assaults to food stores in Lisbon and Porto, immediately followed the departure of the first expeditionary forces to Angola and Mozambique in September 1914. The intensity of popular struggle reached its peak during the four wartime winters. After the Swards Movement, in January 1915, and during the Pimenta de Castro dictatorship, protests, riots, and isolated strikes spread from north to south, including the Atlantic islands. After the defeat of the dictatorship (May 1915), in which popular mobilization was determinant, assaults and strikes became more sporadic. In October a general strike in the Setúbal region involved violent confrontations with the forces of order; it was repeated in the Guimarães industrial area in November. General strikes during this period were also announced in Lisbon, Porto, Braga, Portalegre, and Vila Nova de Famalicão with less impact.

In the first two months of 1916 popular discontent indicated an increasing trend towards transgressive repertoires of collective action. These uprisings were accompanied by an outbreak of sectoral strikes with no apparent connection or central direction, since in this period the newborn national organization remained dismantled. A new upsurge of protests over food are reported in the winter of 1917, culminating in the potato revolution, a popular uprising which trembled the Lisbon and Oporto regions in the late May, with dozens of stores and warehouses assaulted. The government decreed a state of siege and clashes with the Republican Guard resulted in several casualties.

Apart from press releases, correspondence between the local, regional, and national authorities, as well as police reports, reveal important aspects related to this repertoire of collective action. The typology of protest differed in rural and urban areas. The first, described as riots, intended to prevent landlords from hoarding and the second, usually described as assaults, intended to force merchants to comply with the official prices. “Stolen” goods were recorded to have been paid for and there was no significant physical violence. In March 1917 in Vilanova de Cerveira, people “took over the cereal and sold it at public auction.” In December 1916 in the village of Fanhões (in suburban Lisbon), people “took over the bread and the weight balances and sold it at $9 the kilo” and even “delivered $800 to the parish to pay for any damage.”[12]

Several examples of local government reports regarding workers’ and the general population’s demands illustrate how these struggles were threatening, undermining public order and creating tensions within the state. Local community bonds enabled the success of collective action aimed at the apprehension and distribution of goods and were usually guaranteed by the complicity of administrative and police authorities. For example, the country administrator ordered the seizure of foodstuffs in the Lisbon region on 2 February 1917; the Seixal municipal council threatened to resign on 30 January 1917 in support of the people’s claims concerning bread price and quality; and on 23 August 1917 the local priest encouraged assaults in Viana do Castelo.[13]

It is also well documented that the civilian police participated in robberies of bakeries and grocery stores during the potato revolution in Lisbon and that the military refused to repress them. Taking into account the importance of community ties in a city like Lisbon during the first quarter of the 20th century, it’s understandable that the Customs Guard forces refused to crack down on robberies and fraternized with the assailants, while women shouted: “the Guard stands by people.”[14]

The present scrutiny of protests related to consumption and food riots in Portugal also suggest that this typology of collective action does not entail sudden and spontaneous outbursts of anger and despair. On the contrary, the resistance of populations against speculation and hoarding integrates a movement with multiple forms of struggle – propaganda sessions, rallies, presentations to the government, demonstrations, strikes, among others[15] – that only in extreme situations include violent actions. It is the state’s use of force and violence to avoid strikes, demonstrations, or public meetings that induced transgressive repertoires of collective action.[16]

Producers and Consumers Unite: the Connections Between Food Riots and Strikes↑

From the spring of 1917, popular uprisings gave rise to a new cycle of labour struggles, starting with a general strike in the construction sector on the exact same day as the potato revolution. After that, during the spring of 1917, sectoral and general strikes took place in all regions, in parallel with popular uprisings. Protests intensified during the summer, culminating with the postal and telegraph services strike, one of the first to spread through the whole country and which drove an attempt to organize a general strike. It ended with the strikers’ military mobilization and more than a thousand imprisoned.[17]

The reports concerning this cycle of social unrest came to the conclusion that the food riots merged with the labour movement, specially from the spring of 1917, when the workers conferences that took place in Lisbon and Porto, organized by the reborn UON, prioritized the struggle against the untenable cost of living. There were general strikes over the cost of living organized by the local trade union federations such as one in Braga, on 2 and 3 July 2 1917, during which a commission of unionists presented the people´s claims to the civil governor[18] and one in Silves, on 6 December 1917, when workers abandoned their work, requiring the immediate intervention of the subsistence commission.[19]

According to the unionists, this relationship induced the rise of a new political consciousness. The Aurora newspaper, reporting on the tumults in Coimbra at the end of 1917, concluded: “The working classes, after a huge protest movement carried on by the people of this city, that in a gesture of revolt broke into the food warehouses, thanks to the local unions federation activity, begin to awaken (…), understanding that only a conscious organization of its forces will be able to destroy the capitalist regime.”[20]

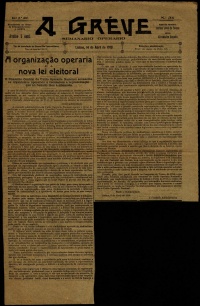

The military coup of December 1917, led by Sidónio Pais, created new expectations among the workers’ leaders. As the union journal wrote: “the revolutionary junta, by abolishing censorship and releasing the social prisoners, has demonstrated not wanting to turn against the organised labour.”[21] Trade unionists delivered Machado dos Santos (1875-1921), member of the revolutionary junta, a summary of the workers’ claims that was subsequently adopted in numerous rallies throughout the country,[22] proposing solutions to scarcity, a wide freedom of association, the establishment of a maximum 8-hour working day, among others.[23]

The prohibition of public meetings and the closure of the trade union national headquarters disappointed expectations and revealed the true character of the new regime.[24] Unionists continued to strengthen labour organization, based on the consumers’ national movement, which culminated in a general strike of all consumers on 18 November 1918. According to the Trade Unions’ Secretary-General, Alexandre Vieira, “never in Portugal, as then, has one worked so intense and widely in the preparation of a strike.”[25]

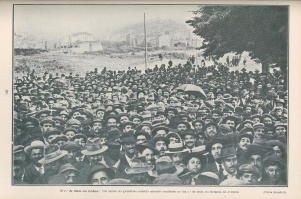

Preparing for the general strike was a vast process of mobilization, such as Portugal had never experienced. Hundreds of initiatives were organized: rallies, meetings, protests, and manifesto distributions in the major cities and manufacturing centres – Lisbon, Porto, Coimbra, Viana do Castelo, Guimaraes, Covilhã, Faro, Funchal, etc. – as well as among rural workers – in Évora, Beja, Portalegre, Sousel, Estremoz, Ferreira do Alentejo, Coruche, Aljustrel, Redondo, Sines, etc.[26] From these initiatives emerged a list of claims directed at the state, involving the defence of producer and consumer interests. In parallel with these general claims, and despite government repression, important sectoral strikes for wages to keep up with inflation were carried out, for example, by rail[27] and tobacco workers.[28]

This unprecedented mobilization resulted in hundreds of new workers’ organizations, which emerged with major mobilization capacity in the early months of 1919, when Sidonismo was defeated and the left-wing governments of the post-war era sought to implement a new program of social reforms.[29] During 1919-1920, along with broad movements over consumption, Portugal’s two main cities and their hinterlands were shaken by extensive struggles over production, which turned repeatedly into general strikes, such as when cork workers achieved an 8-hour day and a 40 percent salary increase[30] or when, 70,000 people went on strike in the Lisbon region between March and April 1920 in solidarity with construction workers.[31] Railway workers’ struggles were particularly dramatic due to their scope, impact, and duration, as well as because of the means of repression implemented by the government.[32]

Popular struggles over food also increased and spread across the country. Among many examples, there was a general strike over the cost of living which paralyzed Viana do Castelo on 3 April 1919. According to the union national newspaper A Batalha, “After assembling the workers in the trade unions headquarters and discussing the causes of the misery we are all in, it was named a commission to report to the district authorities the assembly resolutions which were not to get back to work until the claims were satisfied (…).” The civil governor promised strong measures to prevent hoarding but the strike only ended when, on the next day, the authorities sent the infantry to find the corn that had been stored across the rural parishes.[33]

1 May 1919 strikes were also organized around the cost of living. In commemoration of Labour Day, the scope of geographical mobilization broadened, as did its radicalization and politicization. More rallies than in 1918 took place throughout the country in urban and rural working-class communities, with the dominant motto speaking to the cost of living, but invariably ending with slogans such as: “Long live the workers of the world and the Russian Revolution.”[34]

Conclusion↑

According to Charles Tilly’s (1929-2008) model, food riots or hunger claims were typical forms of pre-industrial societies that were replaced, throughout the 19th century, by meetings, rallies, demonstrations, strikes, and other forms of organized struggle.[35] However, during the First World War, these repertoires resurged not only in Portugal but almost throughout Europe and the United States, which can be explained by the exceptional circumstances and hardships to which people were subjected.

This phenomenon however differed substantially from peasant resistance during the Ancien régime, which in Portugal tended to be spontaneous, localized, and led by members of the elite.[36] One of the main differences is that the war years’ popular upheavals cannot be separated from the emergent labour movement. As Lester Golden and Lynne Taylor argue by analysing the food riots in Catalonia, a symbiotic relationship was created between modern and disciplined working-class struggle and solidarity bonds built in local communities.[37] Usually these protests occurred in reaction to inflation in the prices of foodstuffs or the cost of living and, although they are organized based on social networks, political organizations with a close relationship to the community could be mobilized and their ideas and strategies adapted.[38]

On the other hand, as Manuel Pérez Ledesma verifies using the Charles Tilly model, in this period hunger revolts turned into a modern mass movement: supralocal; autonomous, directed by centralized trade unions; modelling, in the sense that the process and mobilization included manifestos, meetings, demonstrations, and finally the strike; and directed to the state to achieve a reduction of prices.[39]

The empirical data related to the social unrest during and after the war in Portugal points to a bottom-up movement, in which local union leaders mobilized and politicized popular struggle over the cost of living. It is clear that the relationship between the people’s struggle against speculation and hoarding and the collective action driven by professional associations, especially at a local scale, with the creation of hybrid forms of struggle such as community strikes demanding supplies and the seizure and distribution of goods by workers’ associations, among others. Union participation and leadership in consumer protests aligned with an unprecedented expansion of the labour movement, a jump in scale which the foundation of the General Confederation of Labour in September 1919 expresses.

Joana Dias Pereira, Universidade Nova de Lisboa

Section Editor: Filipe Ribeiro de Meneses

Notes

- ↑ Among many others Vidal, Frédéric: Les habitants d’Alcântara: Histoire sociale d’un quartier de Lisbonne au début du 20éme siècle. Villeneuve d’Ascq 2006; Smith, Angel: Anarchism, Revolution and Reaction: Catalan labour and the crisis of the Spanish State, 1898-1923. New York 2007; Bañales, José Luis Oyon: La ruptura de la ciudad obrera y popular. Espacio urbano, inmigración y anarquismo en la Barcelona de entreguerras, 1914-1936, in: Historia Social 58 (2007), pp. 123-150.

- ↑ Among many others Antonioli, Maurizio / Ganapini, Luigi: I sindacati occidentali dall'800 ad oggi in una prospettiva storica comparata. Pisa 1995; Mann, Keith: Forging political identity: silk and metal workers in Lyon, France, 1900-1939. New York 2010.

- ↑ Pereira, Joana Dias: A produção social da solidariedade operária: o caso de estudo da Península de Setúbal. Lisboa 2013.

- ↑ Cabral, Manuel Vilaverde: Forças sociais, poder político e crescimento económico de 1890 a 1914. Lisbon 1979, p. 281.

- ↑ O Sindicalista, 1910-1913.

- ↑ Medeiros, Fernando: A sociedade e a economia portuguesas nas origens do salazarismo. Regra do Jogo 1978, p. 149.

- ↑ Pires, Ana Paula: Portugal e a I Guerra Mundial: a República e a economia de Guerra. Lisbon 2011.

- ↑ Samara, Maria Alice: Sob o signo da guerra [Texto policopiado]: "verdes" e "vermelhos" no conturbado ano de 1918. Lisbon 2001.

- ↑ Palácio Cerezales, Diego: Portugal à Coronhada Protesto popular e ordem pública nos séculos XIX e XX. Lisbon 2011, pp. 211-244. It was this “government of order” that the reorganized labour movement had to face in the last months of the war.

- ↑ Fonseca, Carlos da: História do movimento operário e das ideias socialistas em Portugal, Volume 1. Mem Martins 1980, pp. 141-153.

- ↑ Pires, Ana Paula: Portugal e a I Guerra Mundial: a República e a economia de Guerra. Lisbon 2011, pp. 122-297.

- ↑ Portuguese National Archives. Ministry of Interior: General Direction of Civilian and Political Administration. Received correspondence. Pack 73 and 74.

- ↑ Portuguese National Archives. Ministry of Interior: General Direction of Civilian and Political Administration. Received correspondence. Packs 74-76.

- ↑ Portuguese National Archives. Ministry of Interior: General Direction of Civilian and Political Administration. Received correspondence. Poço do Bispo Fiscal Guard Report, Box 45.

- ↑ President of the municipality of Seixal. Documentary Fundo the Lisbon Civil Governor, Box 122.

- ↑ Administrator of the Barreiro municipality. Letter from 13 September 1918. Documentary Fundo the Lisbon Civil Governor, Box 122.

- ↑ A Aurora, 14-23 September, 1917.

- ↑ Portuguese National Archives. Ministry of Interior: General Direction of Civilian and Political Administration. Received correspondence. Pack 76.

- ↑ A Greve, 6 December 1917.

- ↑ Aurora, 29 December 1917.

- ↑ A Greve, 16 December 1917, p. 1.

- ↑ A Greve, 7 January 1918.

- ↑ A Greve, 1917-1918.

- ↑ A Greve, 9 September 1918.

- ↑ Vieira, Alexandre: Para a história do movimento sindicalista em Portugal. Lisboa 1974, p. 125.

- ↑ A Greve, 27 July 1918.

- ↑ A Greve, 6 June and 4 July 1918.

- ↑ A Greve, 27 May and 6 June 1918.

- ↑ A socialist, comrade Augusto, became responsible for the Ministry of Labour, promulgating broad social legislation, including the institution of mandatory social insurance and the 8-hour working day.

- ↑ A Batalha, 3 May 1919.

- ↑ A Batalha, 18 April 1920.

- ↑ A Batalha, 2 July to 15 September 1919.

- ↑ A Batalha, 3April 1919.

- ↑ Several reports from the General Confederation of Labour newspaper – A Batalha [The Battle] – during May 1919.

- ↑ Tilly, Charles: La France conteste. De 1600 à nos jours, Paris 1986.

- ↑ Tengarrinha, José: Movimentos Populares Agrários em Portugal. Lisbon 1994.

- ↑ Golden, Lester: The Women in Command. The Barcelona Womens’ Consumer War of 1918. In: UCLA Historical Journal 6 (1985), pp. 5-32.

- ↑ Taylor, Lynne: Food riots revisited. In: Journal of Social History 30/2 (1996), pp. 483-496.

- ↑ Ledesma, Manuel Pérez: “El Estado y la movilization social en el siglo XIX Español.” In: Castillo, Santiago / de Orruño, José M.ª Ortiz (eds.): Estado, protesta y movimientos sociales, pp. 220-227.

Selected Bibliography

- Cabral, Manuel Villaverde: Portugal na alvorada do século XX. Forças sociais, poder político e crescimento económico de 1890 a 1914 (Portugal at the dawn of the 20th century. Social movements, political power and economic growth from 1890 to 1914), Lisbon 1979: Regra do Jogo.

- Fonseca, Carlos da: História do movimento operário e das ideias socialistas em Portugal (History of the Labour movement and the socialist ideas in Portugal), Mem Martins 1980: Publicações Europa-América.

- Freire, João: Anarquistas e operários. Ideologia, ofício e práticas sociais. O anarquismo e o operariado em Portugal, 1900-1940 (Anarchists and workers' ideology, office and social practices. Anarchism and the working class in Portugal, 1900-1940), Porto 1992: Edições Afrontamento.

- Ganapini, Luigi / Antonioli, Maurizio: I Sindacati occidentali dall'800 ad oggi in una prospettiva storica comparata, Pisa 1995: Biblioteca Franco Serantini.

- Golden, Lester: The women in command. The Barcelona womens' consumer war of 1918, in: UCLA Historical Journal 6, 1985, pp. 5-32.

- Haimson, Leopold H. / Sapelli, Giulio (eds.): Strikes, social conflict, and the First World War. An international perspective, Milan 1992: Fondazione Giangiacomo Feltrinelli.

- Ledesma, Manuel Pérez: El Estado y la movilization social en el siglo XIX Español, in: Castillo, Santiago / Ortiz de Orruño Legarda, José María (eds.): Estado, protesta y movimientos sociales. Actas del 3er Congreso de Historia Social de España, Vitoria-Gasteiz, julio de 1997, Bilbao 1998: Universidad del País Vasco, Servicio Editorial.

- Mann, Keith: Forging political identity. Silk and metal workers in Lyon, France, 1900-1939, New York 2010: Berghahn Books.

- Medeiros, Fernando: A sociedade e a economia portuguesas nas origens do salazarismo (The Portuguese society and economy at the origins of Salazar’s regime), Lisbon 1978: Regra do Jogo.

- Oyón, José Luis: La ruptura de la ciudad obrera y popular. Espacio urbano, inmigración y anarquismo en la Barcelona de entreguerras, 1914-1936, in: Historia Social 58, 2007, pp. 123-150.

- Palacios Cerezales, Diego: Portugal à coronhada. Protesto popular e ordem pública nos séculos XIX e XX (Portugal à coronhada: Popular protest and public order in the XIX and XX centuries), Lisbon 2011: Tinta da China.

- Pereira, Joana Dias: A produção social da solidariedade operária. O caso de estudo da península de Setúbal numa perspectiva comparada (The social production of workers' solidarity. Case study of the Setúbal peninsula in a comparative perspective), in: Working Papers IHC 5, 2014, pp. 1-20.

- Pires, Ana: Portugal e a I Guerra Mundial. A República e a economia de guerra (Portugal and the First World War. The republic and the war economy), Casal de Cambra 2011: Caleidoscópio.

- Samara, Maria Alice: Sob o signo da Guerra. 'Verdes' e 'vermelhos' no conturbado ano de 1918 (Under the sign of the war: 'green' and 'red' in the troubled year of 1918), thesis, Lisbon 2001: Universidade Nova de Lisboa.

- Smith, Angel: Anarchism, revolution, and reaction. Catalan labour and the crisis of the Spanish state, 1898-1923, Oxford 2007: Berghahn.

- Taylor, Lynne: Food riots revisited, in: Journal of Social History 30/2, 1996, pp. 483-496.

- Tengarrinha, José: Movimentos populares agrários em Portugal (Popular agrarian movements in Portugal), Mem Martins 1994: Publicações Europa-América.

- Tilly, Charles: La France conteste. De 1600 à nos jours, Paris 1986: A. Fayard.

- Vidal, Frédéric: Les habitants d'Alcântara. Histoire sociale d'un quartier de Lisbonne au début du 20e siècle, Villeneuve d'Ascq 2006: Presses universitaires du septentrion.

- Vieira, Alexandre: Subsídios para a história do movimento sindicalista em Portugal de 1908 a 1919 (Subsidies for the history of the trade union movement in Portugal from 1908 to 1919), Lisbon 1977: Edições Base.