The Foundations of Raemaekers work↑

Louis Raemaekers (1869-1956) was born in Roermond, a town in the Netherlands neighbouring the German border, where his father was a prominent member of the liberal camp in the conflict between liberalism and clerical Catholicism. After his training as an art teacher, he became the director of an art school for craftsmen in a provincial town in the centre of the country. In his free time, he worked as a painter of landscapes and portraits and had success as an illustrator and poster designer. In 1906, when he was invited to make editorial cartoons for a national newspaper, it became clear he had found his calling.

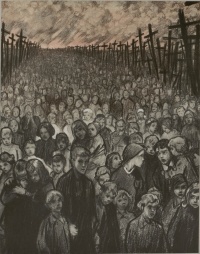

Raemaekers’ working method and style was in the tradition of French and Dutch painters of the late 19th century. Above all, he was influenced by the Swiss artist Théophile-Alexandre Steinlen (1859-1923), who resided in Paris for most of his working years. He got acquainted with Steinlen’s work in the early years of the century, but his influence became most apparent in Raemaekers’ editorial cartoons and wartime drawings. Like Steinlen, Raemaekers used charcoal and Conté crayon, materials that were particularly suited to his rapid way of working, and depicted his figures with strong, dark strokes against a generally blank background. However, what appealed most to Raemaekers was the emotional charge in Steinlen’s drawings and the social compassion he expressed in his work.

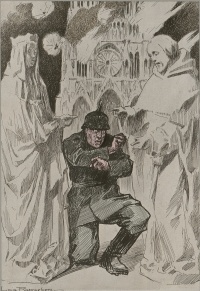

Raemaekers made use of extensive visual symbolism such as national, historical, cultural and Christian symbols, which attests to the ease with which he made use of his broad interests and to his knowledge of these subjects. His frequent references to the Bible and to Christianity were not a reflection of Raemaekers’ own convictions. He came from a very liberal Catholic background and throughout his adult life he was not a churchgoer. His use of well-known biblical metaphors should instead be seen in a historical and cultural perspective and should not be understood to carry a deeper religious significance. Raemaekers was never formally connected to any political party nor did he express any affiliation with any political parties. His political views may have been in line with his conservative-liberal background, when possible, he read newspapers of all kinds of political persuasions.

First World War↑

At the outbreak of the First World War, when the German army invaded Belgium, Raemaekers’ keen sense of justice led him to take the side of the weakest. He expressed himself in scathing, dramatic cartoons for the Dutch newspaper De Telegraaf that quickly found an audience. His attitude, coupled with his fierce drawings attracted the attention of the Dutch government, who carefully monitored the neutral status of the Netherlands. When Raemaekers clearly pointed his finger at Germany as the brutal invaders of Belgium and France, one of his drawings was confiscated. However, Dutch law permitted such accusations as long as the country was not in state of war, so Raemaekers was never formally accused.

Raemaekers’ cartoons quickly drew the attention of neighbouring countries and the foreign press. In occupied Belgium, they were published in clandestine newspapers like La Cravache, De Vrije Stem and Patrie!. In Britain and France, they appeared in the Daily Mail and Le Journal. His first exhibition in London opened in December 1915, attracted many visitors, and received kudos from the press. In France, small albums of picture postcards earned him fame, and in early 1916, he was awarded a medal of the Legion of Honour.

The German government had also become aware of this critic of their war operations, even to the point where they apparently issued a price on his head, although this has never been confirmed by a German source. Nevertheless, this legend became a major factor when Raemaekers moved to London and was engaged by Britain’s War Propaganda Bureau (also known as Wellington House) to play a key role in Allied propaganda efforts. The fact that Raemaekers was citizen of a neutral country and had irritated the Germans, convinced the public that his observations of the alleged German atrocities were true.

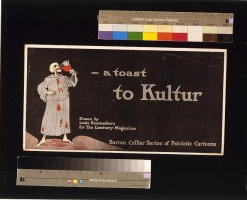

From 1916 onward, his work appeared in pamphlets and albums, and on posters and cigarette cards. His drawings were even recreated as tableaux vivants, and British artists drew copies of his cartoons before live audiences. Wellington House issued Raemaekers Cartoons with a collection of his best work, a leaflet that was translated into eighteen languages and distributed around the world; dozens of exhibitions were organised on all five continents.[1]

During his trip to the United States in 1917, hundreds of American newspapers published Raemaekers’ cartoons. He brought the atrocities of the war into American homes. Soon, the public, not always fully aware of what had happened on those far away battlefields, endorsed the American declaration of war. The popularisation of his work is regarded as one of the largest propaganda efforts of the First World War.[2] Raemaekers gave countless interviews and spoke to numerous influential Americans, acquiring a reputation as “the one man who, without any assistance of title or office, indubitably swayed the destinies of peoples...”.[3]

Raemaekers’ Life after the First World War↑

After returning to London he spent the remaining months of the war working quietly, interrupted only by several trips to the front. He enjoyed being close to the trenches and made hundreds of sketches of soldiers and war situations.

After the war Louis Raemaekers and his wife settled in Brussels. He continued to work for the Dutch De Telegraaf and added the Belgian Le Soir to his list of employers. He focused mainly on the political situation in post-war Europe, but his voice was lost. Most people wanted to forget the horrors of the war. In the Netherlands, where during the war he was criticized for his alleged anti-Dutch actions, it took years before he was finally rehabilitated. That only happened when the threat from Nazi Germany confirmed his anti-German attitude.

At the outbreak of the Second World War Raemaekers and his wife fled to the United States. He wanted to resume his old propaganda work but was unable to keep up with the day-to-day politics. After 1945, he spent another few years in Brussels. In 1953, he finally returned to live in the Netherlands. Raemaekers he died in 1956 in The Hague.

The passion with which Raemaekers strove against everything that was, in his eyes, “wrong”, was rooted deeply in his childhood. The great emotional impact of his work, combined with his neutral background, made him reliable in the eyes of his readers. His clear and harrowing depictions of the war and the strength of the propaganda, made Raemaekers’ message convincing for many people. It made him a key figure in the production of allied propaganda.

Ariane de Ranitz, Independent Scholar

Section Editor: Emmanuel Debruyne

Notes

Selected Bibliography

- Abbenhuis, Maartje: The art of staying neutral. The Netherlands in the First World War, 1914-1918, Amsterdam 2006: Amsterdam University Press.

- Horne, John / Kramer, Alan: German atrocities 1914. A history of denial, New Haven 2001: Yale University Press.

- Raemaekers, Louis: Raemaekers' cartoons, London; New York; Toronto 1916: Doubleday, Page & Co.

- Raemaekers, Louis: The Great War. A neutral's indictment. 100 cartoons, London 1916: Fine Art Society.

- Ranitz, Ariane de: Louis Raemaekers. 'Armed with pen and pencil'. How a Dutch cartoonist became world famous during the First World War, Roermond 2014: Louis Raemaekers Foundation.

- Sanders, Michael / Taylor, Philip M.: British propaganda during the First World War, 1914-18, London 1982: Macmillan.