The Committee and its Origins↑

On 4 February 1918, the committee of the Swiss Federation of Trade Unions (Schweizerischer Gewerkschaftsbund, SGB), the executive board of the Social Democratic Party of Switzerland (SPS), the social democratic faction of the national council, and representatives of the social democratic press founded a committee in Olten, a hub in the Swiss railway network. Its members were Rosa Bloch-Bollag (1880-1922); the editor of the Basler Vorwärts, Friedrich Schneider (1886-1966); the president of the Swiss metalworkers’ and watchmakers’ association, Konrad Ilg (1877-1954); the secretary of the Swiss Federation of Trade Unions, Karl Dürr (1875-1928); the secretary of the Swiss railway crews’ association, August Huggler (1877-1944); and the secretary of the Swiss woodworkers’ association, Franz Reichmann (1880-1941). On 3 March, Fritz Platten (1883-1942), the secretary of the Social Democratic Party of Switzerland, Charles Schürch (1882-1951), the secretary of the French-speaking section of the Swiss Federation of Trade Unions, and Ernest Paul Graber (1875-1956), the editor of La Sentinelle, also joined. On 12 April, the president of the workers’ union of Swiss transportation operators, Werner Allgöwer (1879-1966), followed. In October, he was replaced by the president of the association of Swiss railway employees, Harald Woker (1883-1944); the secretary of the association of Swiss railway employees, Emil Düby (1874-1920); and the president of the association of Swiss signallers, Bernhard Kaufmann (1873-1940). Platten and Reichmann resigned without replacement, in August and October 1918, respectively.

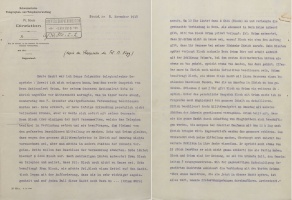

The federal government’s plan for compulsory civilian service, which some feared would militarise work, prompted the foundation of the committee. However, the actual causes were tied to the massive war profits of a small minority whilst large parts of the labour force sunk into impoverishment, and the labour organisations’ exclusion from political decisions as a result of the federal government’s extraordinary war-time powers. Led by Grimm, the committee, which had no statutory authority, developed into the actual executive of the labour organisations. It temporarily pushed the SGB, sectoral unions and SPS into the background. From 4 February to 14 November 1918, it met a total of 21 times, mostly in Bern. It repeatedly sent new requests to the federal authorities, such as a 15-point economic programme with a strong emphasis on food supply (in March), no further increases in milk prices (in April), and eleven demands, especially against the restriction of political rights, for better food supply, wage increases and shorter working hours (in July). By threatening to strike and preparing for it, it obtained various concessions. As the committee had no clearly defined powers, it was more vulnerable to the pressure of radical left-wing currents than the SPS and SGB. It attempted to both restrain these and spread propaganda for the general strike among moderate workers and in rural areas. Right-wing bourgeois circles, especially in western Switzerland, from the beginning tried to discredit the committee as an instrument for a coup and called it "soviet d'Olten". On 7 November 1918, the OAK reacted to a troop deployment to occupy Zurich with a call for a protest strike which on 10 November was extended to a general strike with the proclamation “To the working people of Switzerland!”. It made demands for nine reforms, including unionist (48-hour week), social-political (old age insurance), general policy (re-election of the national council, women’s suffrage), and war-related claims (the obligation to work, army reform, food supply, export monopoly, wealth tax).

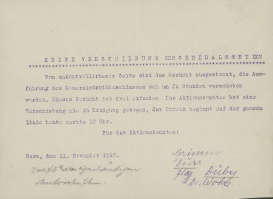

After the military occupation of several cities and an ultimatum from the federal government, the OAK terminated the strike in the early morning of 14 November. In the absence of any criminal offenses, the members of the committee faced trial in a military court in spring 1919. On 10 April, the court sentenced Grimm, Schneider and Platten to six months’ imprisonment each for mutiny, committed through the proclamation of the strike. Attempts to continue an extended Oltener Aktionskomitee in the form of a "Zentrales Aktionskomitee" failed, as did later attempts to form common leadership of the unionist and political labour movements.

The Oltener Aktionskomitee was the first area of the general strike that researchers were able to study after Willi Gautschi (1920-2004) received access to the protocols in the 1950s; at that time, a significant portion of the documents remained sealed in archives as the blocking period had not yet expired.

Bernard Degen, Universität Basel

Section Editor: Roman Rossfeld

Translator: Brier Field

Selected Bibliography

- Degen, Bernard: Richtungskämpfe im Schweizerischen Gewerkschaftsbund, 1918-1924, Zurich 1980: Verlag Reihe W.

- Gautschi, Willi: Das Oltener Aktionskomitee und der Landes-Generalstreik von 1918, Zurich 1955: Affoltern.

- Gautschi, Willi: Der Landesstreik 1918, Zurich 1968: Benziger.

- Gautschi, Willi (ed.): Dokumente zum Landesstreik 1918, Zurich; Cologne 1971: Benziger.

- Oltener Aktionskomitee: Der Landesstreik-Prozess gegen die Mitglieder des Oltener Aktionskomitees vor dem Militärgericht 3 vom 12. März bis 9. April 1919, Bern 1919: Unionsdruckerei.