Introduction: The Significance of Labor↑

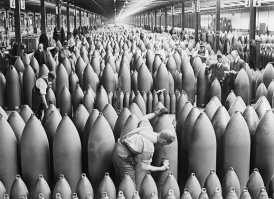

As a conflict of immense size and scale, the First World War was centered around the mobilization of massive quantities of human labor. For all belligerent powers, the management of this human labor in all its forms was a significant problem, as countries struggled to balance the various needs of their armies and their respective societies and economies. In particular, the offensive strategy that developed early in the war, which relied on huge quantities of shells and other war materiel, demonstrated the importance of industry and industrial labor for the conduct of the war. The continued consumption of materiel and human lives throughout the war demanded an extensive mobilization of material and human resources. The mobilization of industry and industrial labor helped to define, in part, the war’s impact on societies across the globe, making the First World War a “total war”.

Historical study of the significance of labor during the war has focused on the economic and industrial problems the war posed, examining the ways that the war altered the organization of industries to meet wartime needs. In order to examine this problem, historians have focused on the ways in which armies themselves directly intervened in the organization of industries and labor for the purposes of meeting immediate military needs. This study has led historians to examine the ways that this industrial reorganization changed relationships between states and economies, as well as other political consequences of wartime labor demands. In addition, historians have increasingly examined the social impacts of this industrial reorganization by focusing on the laborers themselves, raising questions about short-term and long-term changes in gender relations due to the war’s mobilization of both male and female labor. Most recently, historians have taken this focus on laborers to examine the work done by colonized peoples in Africa and Asia, by contract laborers from China, and by coerced populations in occupied territories, all of which demonstrate the global reach of the First World War.

The Organization of Labor↑

The central role played by industrial production in the First World War led to a series of changes in the ways in which countries organized labor. Within all of the major belligerent powers, the war altered the division of labor in society, patterns of employment, the size and scale of industries and conditions of work.

Problems of Production and Labor↑

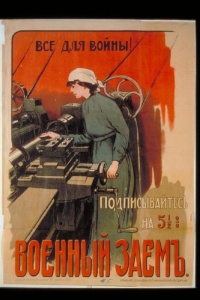

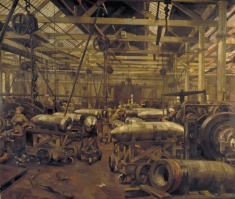

For Russia and France in particular, one of the central industrial problems posed by the First World War was the production of sufficient quantities of munitions and other war materials. In Russia, this problem was exacerbated by the massive size of its army compared to its relatively modest pre-war industrial production. While Russia had undergone an extremely rapid period of industrialization dating back to the 1880s, both total and per capita industrial output in Russia still lagged behind Germany, France, and Britain by the outbreak of the war. With the conscription of around 5.1 million men in the second half of 1914 alone, Russian army demands immediately led to a major shortage of all forms of labor at home, and most acutely in industry. Private industry was mobilized for the production of shells, previously the responsibility of state arsenals, but a meeting in September 1914 revealed that Russian private industry was only capable of producing one-third of the estimated number of shells needed, leading Russia’s Main Military Administration (GAU) to employ American firms to produce additional arms and shells.[1]

France had far greater industrial productive capacity than Russia at the outbreak of the war and remained the largest Allied producer of arms throughout the war, despite having to import coal, coke, iron, and steel.[2] Like Russia, France’s pre-war munitions production was undertaken primarily by state arsenals, a situation that was reversed within the first year of the war, when private corporations became the dominant arms producers. Like all of French industry, the munitions industry experienced shortages of labor throughout the war, particularly from the spring of 1915 onwards. Unlike Russia, though, France had struggled to meet the labor needs of industrial production for several decades prior to the outbreak of the war, largely due to its slow population growth. The First World War exacerbated this earlier trend, leading to various attempts by the French state to reform industrial production under the leadership of Etienne Clémentel (1864-1936), the Minister of Commerce between 1915 and 1919, and Albert Thomas (1878-1932), the first minister of the newly-created Ministry of Armaments and War Production.[3]

Problems of production and labor for both France and Russia were intensified by the loss of major industrial regions during the war – the north-east of France and Russia’s European territories, particularly in Poland and the Baltics. For France, this meant the loss of important coal and steel producing regions, leading French industries to increase their reliance on imports of these materials. For Russia, the territorial loss was more significant, with a loss of approximately one-third of its factories, 10 percent of its iron and steel production, and 40 percent of its chemical industry.[4] While the Russian Empire was able to move some of its stock and laborers from its lost territories to regions further east, more than half of the industrial capacity from these territories was lost, further compounding Russia’s problems with production and labor.

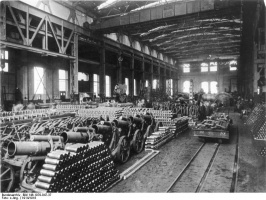

Germany also faced challenges of meeting its production needs early in the war, largely due to the Allied naval blockade, which cut off supplies of key materials for the production of munitions. In addition, like France and Russia, Germany experienced a decline in the labor force due to conscription, although this decline was not as significant over the course of the entire war as the labor shortages faced by France or Russia.[5] Nevertheless, German industries at the beginning of the war faced a similar dilemma to those in France and Russia – how to produce sufficient quantities of war materials for the conduct of a war on such a massive scale. While the Allied naval blockade was initially concerned with acquiring sufficient materials for munitions production, Germany also struggled with mobilizing sufficient numbers of industrial laborers to meet production needs.

Thus, for the major belligerent powers, industrial production was a central problem throughout the First World War.[6] The contours of this problem varied, as did the ways in which different countries encountered and responded to the problem of mobilizing industrial laborers.

Changes in Patterns of Employment and Industrial Organization↑

Across the major belligerent powers, industries and employment were altered to meet the needs of wartime production. In some states, such as Russia and Italy, the total industrial workforce increased between the start and end of the war, while in others, such as in Germany and Britain, the total industrial workforce decreased. Overall, the numbers of laborers employed in particular industries related to wartime and combat needs increased, while other industries experienced significant decreases in employment.[7]

The re-orientation of production towards war-related industries – such as metallurgical industries, machine-building industries, chemical industries, electrical industries, and petroleum industries – was a pattern that occurred in all major belligerent countries. Employment decreased in industries such as textiles, food production, construction, and mining, at the same time as war-related industries saw increases in employment. For example, in the Italian city of Turin, Fiat expanded its workforce dramatically from 3,500 in August 1915 to 16,000 in December 1916 to over 40,000 by the end of the war, drawing in women, youth, and agricultural workers to be mobilized for automobile production.[8] Similarly, in Paris, Renault quadrupled its workforce over the course of the war to over 20,000 workers, part of a broader shift to war-related production that included approximately 300,000 workers in the Paris region by 1917.[9]

Related to this structural change in the workforce was an increase in large-scale production with factories employing larger numbers of workers. Shifts within countries’ total labor force from smaller-scale production and with factories or workshops employing smaller numbers of workers, towards larger factories employing between fifty to 100, or over 100, workers reflected the shift to war-related industries. These industries were, after all, part of the so-called “second industrial revolution” in the three or four decades preceding the war, and were more likely to be organized on a large scale even prior to the war. The expansion of those industries during the war, therefore, led to a corresponding shift towards large-scale production, where laborers increasingly worked in large factories, which continued to increase in size during the war. For example, the average metal-working factory in Russia increased from 160 workers in 1913 to 234 workers in 1916.[10]

In addition to these two structural changes in the workforce and industrial organization, many countries also saw increases in semi-skilled and unskilled workers, with declines in numbers of skilled workers. This shift is, however, much more complex and more difficult to assess than the previous two changes in industrial organization. First of all, the categories of skilled, semi-skilled, and unskilled, have been increasingly called into question by labor historians, as the boundaries between levels of skill are often understood to be fluid and contested, reflecting political struggles rather than material conditions of production. Second, the extent to which unskilled and semi-skilled work increased at the expense of skilled work varied across particular industries and countries. In France, this shift to semi-skilled and unskilled labor during the war appears to have been quite significant, both in terms of the numbers of workers and their relative proportion in the total workforce. Similarly, in the case of the Italian firm Fiat, discussed above, the expansion of the workforce corresponded to a de-skilling of labor, where the trades associated with automobile production shifted from being dominated by a skilled, working-class elite, to large numbers of rapidly-trained, and therefore semi-skilled, new workers.

Wages, Working Conditions, and Living Standards↑

The development of structural shifts within the major belligerent countries’ workforces away from skilled labor takes on particular significance because it is related to changes in wages, working conditions, and living standards. In particular, one major trend in wages across most belligerent powers was the decrease in wage differentials between skilled, semi-skilled, and unskilled work. In Germany, while nominal wages increased for most industrial workers throughout the war, they did so to varying degrees. Both male and female workers in war-related industries saw the greatest increases in nominal wages, with the biggest increases going to women in metal manufacturing, who saw a 324 percent increase, and men in the electrical industry, who saw a 298 percent increase in nominal wages. At the same time, averages wage differentials between unskilled and skilled workers in Germany decreased throughout the war, and in the second half of the war wage differentials between male and female workers declined as well, producing a more uniform wage rate across all industrial labor.[11] These two trends of increasing nominal wages and decreasing wage differentials among skilled, unskilled, and semi-skilled workers, as well as between male and female workers in Germany were paralleled in Russia and Britain, if not all major belligerent powers.[12]

However, while this general pattern of decreasing wage differentials among all industrial workers developed across industries in the aggregate, the relative wages of unskilled, semi-skilled, and skilled workers varied among particular industries. For example, wage differentials decreased in the British engineering industry, but within the British shipbuilding industry, differences in wages between skilled and unskilled work persisted throughout the war.[13] Thus, it is difficult to generalize about a leveling of all industrial work as a result of the war, particularly from looking only at nominal wages.

What is clear about wages across Europe during the First World War, though, is that real wages saw significant declines. Much of this decline in real wages was due to increasing prices of consumer goods, particularly food, which came about, in part, due to countries’ shifting labor towards war-related production. In Vienna, one of the most important industrial centers of the Dual Monarchy of Austria-Hungary, foodstuff prices rose between 300 and 1,000 percent between 1914 and 1918. This lead to a decrease in real wages to 64 percent of their pre-war levels in 1916-17, and to a low point of 37 percent of their pre-war levels in 1917-18.[14] Average real wages declined less dramatically in France, by 20 percent between 1914 and 1918, and while figures are less clear for Germany, various measures seem to indicate a decline of about 25 percent in real wages there as well.[15] One exception to this pattern occurs in Russia, where real wages in the munitions industry increased between 1914 and 1916, compared to a decrease of 15 percent in real wages in non-war-related industries, for an overall net increase of about 8 percent.[16] However, in the city of Petrograd, one of Russia’s major industrial centers during the war, and later a center of revolutionary activity, real wages fell by approximately 25 percent between 1913 and the start of the Russian Revolution in February 1917. Some of this apparent disparity in the Russian experience is explained by the massive fall that real wages took place in Russia over the winter of 1916-1917, a period of food deprivation across much of Europe, known as “turnip winter” (Kohlrübenwinter) in Germany. Thus, the decline in real wages across continental Europe was not a linear or uniform one over the course of the entire war. In some cases, real wages increased early in the war and saw a significant decline in the last two years of the war, producing a net decline for the entirety of the war. In other countries, such as Britain, real wages declined for the first half of the war but saw an increase for some groups after mid-1916, largely due to state subsidies, maximum price regulations, and other economic controls.[17]

This discrepancy between increasing nominal wages and decreasing real wages contributed to growing discontent among industrial workers across the belligerent states, a discontent that was further reinforced by changing working conditions. In particular, the length of the working day and work week was often increased. In Austria-Hungary, the working day in war-related industries was increased to thirteen hours, while legislation limiting work on Sundays and holidays was repealed. In Italy, the work week was officially extended to seventy hours, while in practice it was closer to seventy-five hours. Similarly, in Germany and Russia, the average working day and work week increased over its pre-war levels, and in France the twelve hour work day became the norm in factories engaged in war-related production, such as the factories of Renault in the Paris region.[18] At the same time as the working day and work week was extended in these countries, the pace of work was often increased, in some cases using various techniques of “scientific management” pioneered by Frederick Taylor (1856-1915), accelerating a trend in working conditions that had developed in the decade or so before the war. One consequence of combining a speed up in production with a longer working day appears to have been an increase in industrial accidents during the War. In Renault’s Boulogne-Billancourt factory outside of Paris, for example, twenty-six workers died when new machinery was being installed.[19] Similar accidents and increasing mortality and injury rates were noted in many industries of the other major belligerent powers during the war.[20]

These increases in industrial accidents, combined with the longer working day and work week, and overall decreases in real wages, indicate that living standards for many, if not most, industrial workers declined during the war. The extent of this decline varied depending on many factors, including location, industry, relief offered by state economic controls, and the discrepancies between particular periods of the war.

Mobilizing Women and Men as Laborers: Gendered Divisions and Distributions of Labor↑

While most belligerent countries made attempts to keep skilled, male, industrial workers employed in production early in the war, this became increasingly difficult as the war continued and casualties mounted. In addition, the shift towards war-related industries meant that larger numbers of workers were needed in those industries and fewer workers were needed in other industries. One of the first major changes in employment during the war was increased unemployment for workers in some of those non-war related industries, such as the garment and textile industries. The German government passed several laws in 1915 and 1916 reducing production and hours for the textile industry and then offered assistance for unemployed workers in the textile and garment industries.[21] Unemployment in these industries, in Germany or elsewhere, affected women far more than men, as women made up the overwhelming majority of the labor force in the garment and textile industries. Thus, one of the early impacts of the war on the gendered distribution of labor was to decrease women’s employment and increase men’s employment.

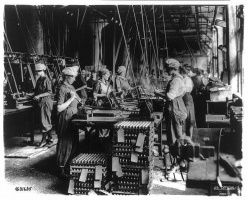

However, this gendered distribution of labor continued to be further altered throughout the war, as working-class women across the major belligerent countries were increasingly recruited to work in war-related industries. In Russia, women employed in the metallurgical and machine-building industries increased from about 6 to 18 percent of the total labor force between 1913 and 1916, and similar gains were seen in the engineering and chemical industries, leading women to increase their total presence in the industrial labor force from 30 percent in 1913 to 40 percent in 1916.[22] In Paris, women made up 18 percent of the workers in war-related industries in 1915, a figure that rose above 25 percent in 1917. However, France also found a way to maximize its male labor force during the war by sending conscripts who were skilled industrial workers back from the front to work in industry while remaining under military discipline. Such “mobilized workers” (mobilisés) made up 30 percent of the labor force at the Renault factories in 1917; another 30 percent of workers in these factories were women.[23] In Britain, women were increasingly employed in munitions factories following the creation of the Women’s War Registrar in the summer of 1915, and a 1919 report by the War Committee on Women in Industry placed the number of women who were munitions workers in Britain by the end of the war at approximately 900,000. However, women were employed across all industries and forms of employment during the war, and rose to nearly half of Britain’s total labor force by the period between July 1916 and June 1917.[24]

This substantial increase in the percentage of women in the British labor force raises questions about the extent to which women who had not previously worked outside the home entered the labor force during the war. In most countries, women engaging in industrial work throughout the war appear to have shifted employment, either from one form of industrial employment to another or from non-industrial employment (such as domestic service) to industrial work. This was particularly the case for women who became employed in factories engaged in war-related production. In Austria, for example, while women worked in many jobs “which had been seen as typical men’s jobs like welding, cutting, pressing, the handling of boring-machines and lathes, etc.,” many of those women working in munitions factories entered those jobs after working to produce army uniforms as outworkers at home.[25] Indeed, the persistence of “outwork” or “homework” during the war – where women engaged in production in their own homes, and coordinated such homework with work as caregivers and maintaining households – continued to be a significant way that women participated in the industrial workforce. In Germany, most women entering the industrial workforce for the first time during the war engaged in some form of homework, albeit homework that was significantly altered to meet the demands of military production, where homeworkers made “gunlock covers, baskets for shells and cartridges, military blankets, gasmasks, fur coats, sandbags, uniforms and shoes.”[26]

Women who did engage in factory work in war-related industries experienced a mix of continuity and change in the material conditions of work and its cultural construction during the war. In Britain, trade unions, industrialists, and the government agreed upon the “dilution” of labor in war-related production, allowing for changes in production that shifted labor towards semi-skilled and unskilled labor. Female workers were often referred to as “dilutees” or “substitutes,” reflecting a dual-status as women and less-skilled workers. Similarly in France, women entering factories in war-related industries became known as “replacement workers” (remplaçantes), the most famous of which were female munitions workers (munitionettes). The use of women as “replacement workers” was encouraged by the French state during the battle of Verdun in the spring of 1916, when Minister of Munitions Albert Thomas wrote to the heads of industries contracting with the government and ordered them to replace men with women and “to develop new technical processes to increase production and help the women in their work.”[27] Thomas’s comment indicates a parallel attempt taken in France to the British “dilution” of labor and a similarity in the cultural construction of women’s work in war-related industries.

In both the British and French cases, female “replacement” or “substitute” workers in war-related industries earned lower wages than their male counterparts, but women’s wages in war-related industries were often higher than in industries defined as “women’s work.” Thus, women’s wages in war-related industries resulted in some mixed experiences faced by female industrial workers during the war – wages that suggested their work was not the same as “women’s work” yet also not equivalent to “men’s work.” This ambivalent status of women’s industrial work during the war was reinforced by the growing public discourse late in the war that women working in large-scale industries were acting outside gender norms, and possibly even causing problems for nations and their survival after the war. This attitude was expressed by Louis Loucheur (1872-1931), France’s new Minister of Armaments, on 13 November 1918, just two days after the armistice, when he informed women working in war-related industries:

Loucheur’s statement ended up reflecting what became the long-term trend for the labor force in most belligerent countries. While the war increased the numbers of women in the labor force, particularly in large-scale industrial production in war-related industries, many of those women became unemployed or returned to industries defined as “women’s work” following the end of the war. For example, Citroën cut its workforce in its Javel factory “from approximately 11,700 workers, of whom about 6,000 were women, to 3,300 workers, all male” by February 1919.[29] Also by 1919 in Germany, many more women had become housewives at the end of the war than was expected in estimates made just one year earlier.[30] Similarly, by 1920 in the United States, women made up a smaller percentage of the labor force than they had in 1910.[31] In this sense, the mobilization of women’s labor for the war effort reflected a temporary and limited change in the gendered division and distribution of labor, a change necessary to maximize the numbers of laborers mobilized in order to meet the productive demands of the war. This wartime change, however, did not directly lead to broader social and cultural changes in the gendered order of societies after the conclusion of the war.

Mobilizing Laborers from Across the World↑

The attempts by industrialists and belligerent states to maximize labor for the purposes of increasing productivity also led to the employment of international labor from outside of the involved nations. This included the mobilization (and coercion) of laborers from overseas colonies, the mobilization of labor from China with the assistance of the new Chinese republican regime, and the mobilization of forced labor within territory controlled by belligerent states. These laborers worked in theatres of war, within their respective colonies and occupied territories, and even in the metropoles of belligerent states.

Colonial Labor↑

In employing laborers from their overseas colonies, European states mobilized geopolitical advantages in an attempt to address their labor needs. Many of these labor needs were located within industries and agriculture inside European states, as discussed above. In the Italian firm of Fiat, for example, laborers from Italy’s colony of Libya were forcibly recruited and employed.[32] The state that made the most extensive use of colonial labor in its factories and fields in the metropole was France. By the beginning of 1915, the French government and industrialists started recruiting laborers from France’s colonies, as well as immigrant workers from other European states. These workers had to travel to France to work for private industry and agriculture, with the French government providing assistance in the transportation, lodging, and policing of the foreign labor force .

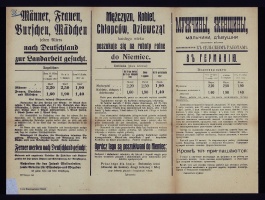

These laborers came from the French colonies of Indochina, Algeria, Morocco, Tunisia, and Madagascar – a selection based on French racial thought that distinguished “martial races” (such as peoples from West Africa) from those more “suited” to labor.[33] Ultimately, over 185,000 laborers from France’s colonies came to work in France, approximately 78,566 from Algeria, 48,955 from Indochina, 35,506 from Morocco, 18,249 from Tunisia, and 4,546 from Madagascar.[34] Initially, the French sought volunteers from the colonies, conducting recruitment campaigns such as the one begun in Vietnam in December 1915, with the assistance of the Vietnamese royal court in Hue, that promised 200 francs to each volunteer, family allowances, pensions, titles, honors, and exemptions from taxes.[35] However, recruitment campaigns similar to this one in North Africa had limited success, and the French authorized the use of military conscription in a decree on 14 September 1916 in order to obtain larger numbers of workers from Algeria and Tunisia. This made French “recruitment” of colonial workers a form of coerced labor, sometimes enforced by establishing quotas of laborers from specific regions of a colony (such as in Indochina) and sometimes by holding labor drafts.[36]

This coercion of colonized peoples in the recruitment process was reinforced in the transport, placement, and supervision of these workers while in France. The French War Ministry created the Colonial Labor Organization Service (Service de l’Organisation de Travail Colonial or SOTC) in January 1916, which was responsible for supervising the entire process from recruitment to employment of colonial laborers, placing colonial laborers directly under military organization. These laborers were shipped from the colonies to Marseille, a particularly arduous journey for those coming from Indochina who were frequently exposed to outbreaks of disease on board ships.[37] In Marseille, colonial workers were organized by a process the French called regimentation (encadrement), in which contingents based on nationality were sent out to industrial and agricultural employers.[38] Most of these colonial workers were employed in factories in war-related industries, especially munitions plants, although some worked at the docks in port cities, on construction of new factories, and even in specific agricultural sites. These workers typically signed contracts with a specified wage rate prior to leaving their colonies, which was equivalent to the wages of a “typical” French worker at the start of the war. However, with the escalation of nominal wages throughout the war, colonial workers became the lowest-paid workers in France, particularly those employed in munitions plants, which tended to have some of the highest wages for unskilled or semi-skilled French industrial workers. In addition to these low wages, the quality of housing and food for colonial workers was often quite poor, with makeshift barracks of various sorts, although these living conditions could vary widely depending on the specific location in France.[39]

While munitions factories were among the largest employers of colonial labor within France, a movement within many of the colonies of the British Empire led to attempts to produce munitions inside those colonies, creating another way in which colonial laborers were mobilized by the war. In a meeting in London on 12 August 1915, the British Ministry of Munitions discussed several colonies’ plans to produce munitions with representatives from India, Australia, South Africa, New Zealand, Ceylon, the Federated Malay States, Nigeria, and Singapore. Of these colonies, the British Ministry of Munitions placed the most hope in India, which had an established steel industry and system of armaments production, and between 1915 and 1917 India manufactured 1.3 million shells.[40] In addition, attempts by the British colonies to produce munitions established economic linkages among India, Australia, and New Zealand. Ultimately, laborers in Canada became the largest group of colonial laborers producing shells for Britain, largely due to practical shipping considerations and Canadian industrial development.[41]

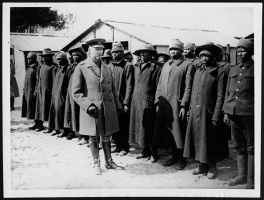

In addition to mobilizing colonial labor for wartime production needs, the British, and to a lesser extent the French, also employed colonial laborers in war-related labor in several theatres of war. Near the Western Front in 1918, for example, Britain mobilized over 300,000 workers in militarized labor corps, companies, and battalions, including the Canadian Labour Battalions, South African Native Labour Corps, Indian Labour Companies, Fijian Labour Company, and the Cape Coloured Battalion.[42] These laborers engaged in wide range of work, including transport, trench digging, construction, engineering, and communications work. Prior to the start of the war, the Indian Labour Companies existed as part of the Indian army and included more than 45,000 workers. Other groups of laborers were quickly recruited, often in a coercive manner with quotas and threats from local magistrates to village leaders.[43] The British employed these laborers extensively near the Western Front but also in other theatres of war, including occupied territories of the Ottoman Empire, where workers from India, Mauritius, Palestine, Persia, and Egypt worked as porters, dockworkers, construction laborers, artisans, and drivers. In addition, both the British and French also recruited local populations from occupied Ottoman territories, including Arabs, Kurds, and Persians, and organized them into labor contingents for building roads and camps, among other forms of work.[44]

Chinese Labor↑

In addition to recruiting laborers from their overseas colonies with various levels of coercion, Britain and France also employed laborers from China. This initiative was developed in part by the active efforts of the relatively new Chinese republican government and Chinese elites. In particular, Liang Shiyi (1869-1933), a policy advisor to the Chinese president Yuan Shikai (1859-1916), presented a “laborers in the place of soldiers” (yigong daibing) strategy as a way of involving China in the war as early as 1915. While Liang’s plan did not have immediate success, it laid the groundwork for later arrangements with the French and the British.[45] The Chinese government established the Huimin Company to recruit laborers for the French in 1916, focusing on laborers from Northern China, and the French also signed separate agreements with other Chinese companies to recruit in Shanghai and the southwestern provinces of Yunnan and Sichuan. The British, however, recruited Chinese laborers directly themselves in the Northern province of Shandong with some support of the Chinese regime in 1917, in exchange for a presence at a future post-war peace conference.[46] Britain and France also made separate arrangements for the transport of laborers from China, with the French sending laborers West across the Indian Ocean and eventually via the Suez Canal to Marseille, and the British sending laborers East across the Pacific Ocean to Canada, then by secret train transport across Canada from Vancouver to Halifax, and finally by ship across the Atlantic Ocean to Northern France.[47]

Approximately 140,000 Chinese workers who arrived in France between 1916 and 1918. The approximately 40,000 Chinese laborers who worked for the French did so in almost ninety separate locations across France, including major industrial centers and port cities. French employment of Chinese workers in war-related industries paralleled their use of laborers from their colonies in North Africa, Southeast Asia, and Madagascar. The contracts created by the Huimin Company specified the wage rate for Chinese workers that - like for colonial workers - soon became among the lowest wages for industrial workers in France due to wartime increases in nominal wages, which were not applied to Chinese (or colonial) workers. In response to meager wages, food rations, and working conditions, Chinese workers organized strikes, often of fairly short duration but with some limited successes.[48]

The approximately 100,000 laborers who worked for the British were concentrated in northern France, and were organized as the Chinese Labour Corps (CLC) and based in the town of Noyelles, which served as a hospital and reception center for newly-arrived laborers. Like workers organized in similar labor corps from British colonies, the concentration of this work relatively close to the Western front meant that most Chinese laborers working for the British engaged in work that was directly related to combat operations, particularly after China renounced its neutrality and officially joined the Allied side in September 1917. Such work included machine repair, road repair and construction, and especially trench digging, for which Chinese workers became particularly well regarded. One British officer commented that: “I have found the Chinese laborers accomplish a greater amount of work per day in digging trenches than white laborers”.[49]

The British employment of CLC close to the Western Front meant that these laborers also worked in cleanup operations after the end of the hostilities, burying bodies, removing barbed wire, and other tasks. The continued presence of the CLC after the end of the war caused some conflict in Belgium, where Flemish views of Chinese laborers turned decidedly negative in contrast to largely positive views of members of the Indian Labour Corps´.[50]

Forced Labor↑

In addition to encountering and interacting with Chinese and Indian laborers working for the British, Belgian civilians in areas occupied by Germany were themselves recruited as laborers. As early as the fall of 1914, German industrialists sought to recruit Belgian workers, particularly highly-skilled workers who had become unemployed following the German occupation. Over the first two years of the war, the German Industrial Office in Brussels (Deutches Industriebüro, or DIB) recruited approximately 30,000 workers, not nearly enough to meet German industry’s needs.[51] In the fall of 1916, Germany began the “forcible recruitment” of Belgian laborers, initially organized into “Civil Workers Battalions” (Zivil-Arbeiter Bataillone, or ZAB) under direct military control. Approximately 62,000 Belgian and northern French workers were forced into the ZAB, and many of these workers were deported to Germany to work in German factories. This coercion of laborers also increased the number of Belgian workers who were “voluntarily” recruited by German industrialists in numbers up to 160,000 by the end of the war.[52]

These efforts to forcibly mobilize Belgian labor were not Germany’s first attempts to employ forced labor. Between the summer of 1915 and the fall of 1916, German officials in the occupied territories of the Baltic and north-eastern Poland (known as Ober Ost) forced tens of thousands of local workers into work in road and railroad repair and construction, agricultural labor, and clearing forests. This initial period of forced labor was augmented in the fall of 1916 with the creation of the ZAB, but workers primarily remained in the occupied territories of Ober Ost, rather than being deported to Germany, like many of the Belgians who were coerced into work at the same time. However, approximately 110,000 workers from the occupied territory of Government-General of Warsaw were recruited by the German Labor Agency (Deutsche Arbeiterzentrale, or DAZ) by spring 1916 and joined the 300,000 Polish women and men who were already working in Germany.[53]

Germany was not, however, the only state to employ forced labor during the First World War. The large land-based empires involved in the war – Austria-Hungary, the Russian Empire, and the Ottoman Empire – all engaged in various practices of forcing local populations into work, either within their own territories or in newly occupied territories. In 1916, Russia initiated a plan of drafting laborers from the empire’s “foreigners” (inorodtsy) in the Central Asian territory of Turkestan, with the hopes of conscripting 390,000 local laborers to meet the demands of the cotton harvest, among other labor-intensive activities. This labor draft met with intense resistance and was a major contributor to the 1916 revolt in Central Asia, and ultimately the numbers of laborers conscripted was far less than the quota expected by Russian authorities.[54] In addition to the Russian attempts at coercing local populations, Austria-Hungary mobilized forced labor in occupied regions of Italy, Albania, Romania, Montenegro and Serbia, while the Ottoman Empire created “Workers’ Battalions” that included approximately 25,000 to 50,000 Armenians, Greeks, and Syrians, for the purpose of constructing roads and other infrastructure.[55]

Labor Politics from Above and Below↑

The creation of workers’ battalions in occupied territories, colonial workers’ labor corps, and government bodies that supervised the recruitment and organization of Chinese laborers, all demonstrate ways in which wartime states were involved in mobilizing labor. Labor was, therefore, a major political problem during the First World War, and not just a matter of economy and society. Wartime states created new policies and organizations to respond to this political challenge, and labor organizations and political parties engaged in political struggles on behalf of workers.

State Regulation and Social Legislation↑

While they did not engage in direct control of production, most wartime states created specific ministries and organizational systems in an attempt to regulate production in ways most useful to the war effort. Britain created a Committee on Production in early 1915 to investigate industrial problems, and eventually created a separate Ministry of Labour in 1916, with the goal of ensuring labor peace in order to make sure private industry met wartime needs.[56] France created the “consortium system” to control the importing of raw materials and the setting of prices for finished goods, organized under the Ministry of Commerce by Etienne Clémentel. Albert Thomas later created a Worker Service to regulate the workforce in armament factories, eventually directing this under the new Ministry of Armaments in 1916.[57] While this state regulation of labor by Britain and France could produce paternalist labor policies that protected workers – Thomas was a socialist and British unions had a say in the Ministry of Labour – their goal was to maximize wartime production. Similarly, Germany introduced the Auxiliary Service Law (Hilfsdienstgesetz) in December 1916, which required all German men between seventeen and sixty years old to work in war-related production, while at the same time creating arbitration committees and allowing workers to file collective grievances.

Such state efforts to maximize labor productivity led to mixed results in the area of social legislation. In the Austro-Hungarian Empire, for example, regulations limiting work on Sundays and holidays, as well as prohibitions on night work for women and youth were repealed during the war, and factories deemed to be of military importance were placed under the War Production Law (Kriegsleistungsgesetz) with the working day extended to thirteen hours.[58] In Britain and France, however, new kinds of state subsidies were introduced during the war, such as rental control and family subsidies. Germany also introduced family allowances for conscripted soldiers’ families, and unemployment assistance for textile workers, both of which were attempts to regulate labor and encourage more women to work in war-related industrial production.[59] In Germany’s case, however, such social legislation was less successful in expanding the industrial labor force, and providing material assistance to workers than in Britain and France. Nevertheless, new social policies created primarily during the second half of the war reflected an increase in the political significance of labor politics, which was due to both wartime production demands and the expanding political power of labor organizations and workers’ political parties.

Workers’ Politics↑

Many labor organizations and political parties provided early, if somewhat qualified, support for the war. Reform-minded labor leaders in Britain, France, Germany, and the United States saw this support as a way of advancing their interests in response to the expanded need for industrial labor during wartime.[60] Labor organizations’ efforts to engage with the state led to a wartime expansion in trade unionism in Britain and France, and an increasing role of Labour and Socialist Parties in government ministries and organizations.[61]

As the war went on, there were increasing protests in response to state efforts to maximize production, structural changes in industries, and declining real wages, safety and living conditions over the course of the war. While strikes declined significantly across all major belligerent countries for the first year of the war, they began to increase at a slow rate in 1916 and then substantially in 1917. Some of these strikes were clearly responses to major declines in living standards, such as the “hunger strikes” in Austria, which made up 70.2 per cent of all Austrian strikes in 1917.[62] These 1917 strikes had a major impact on the Austro-Hungarian state, leading to the creation of a Public Food Office and a new Ministry of Social Welfare, among other major social and political changes.[63] 1917 also saw strikes and the beginning of the revolution in Russia, in addition to a record number of strikes across the United States and a growing strike wave that precipitated the failed 1918-1919 revolution in Germany. These periods of increasing radicalization of workers’ politics at the end of the war and its immediate aftermath demonstrated the increasing significance of labor unions and dovetailed with splits in socialist political parties along revolutionary versus reformist lines, leading to lasting changes in workers’ political organizations throughout the 20th century.

Conclusion↑

The radicalization of workers’ politics by the end of the First World War, as well as states’ new social policies, reveal some ways that the war caused significant changes in labor politics that continued to define political and social struggles throughout the 20th century. Outside of this change in labor’s political significance, many of the changes in the social organization of industrial labor were largely temporary, due to the conditions of the war itself, such as changes in the gendered division of labor and the mobilization of colonial labor, Chinese labor, and forced labor in occupied territories. The temporary nature of these changes suggests that the war’s impact on the social organization of labor could be seen to some extent as a limited disruption, rather than a major reorientation of societies across the world. Nevertheless, wartime reorganization of industrial labor towards large-scale production, and the increasing significance of semi-skilled and unskilled labor, indicate ways in which the war accelerated social and economic changes across all major belligerent countries, and the expanding significance of labor politics demonstrates the lasting impact of the war well after the fighting was concluded.

Steven E. Rowe, Chicago State University

Section Editor: Pierre Purseigle

Notes

- ↑ Gatrell, Peter: Russia’s First World War. A Social and Economic History, Harlow 2005, pp. 22-23.

- ↑ Hardach, Gerd: Industrial Mobilization in 1914-1918. Production, Planning, and Ideology, in: Fridenson, Patrick (ed.): The French Home Front, 1914-1918. Providence 1992, pp. 62-63.

- ↑ Godfrey, John: Capitalism at War. Industrial Policy and Bureaucracy in France, 1914-18, New York 1987, pp. 86-91, 184-188.

- ↑ Gatrell, Russia’s First World War 2005, p. 29.

- ↑ Kocka, Jürgen: Facing Total War. German Society, 1914-1918, translated by Barbara Weinberger from Klassengesellschaft im Krieg. Deutsche Sozialgeschichte 1914-1918, Leamington Spa 1984, p. 17.

- ↑ One result of the production problems faced by European states was the opening of markets that allowed for the expansion of Japanese production and shipping by mid-1916, particularly in armaments and textiles. Cf. Dickinson, Frederick R.: War and National Reinvention. Japan in the Great War, 1914-1919, Cambridge, MA 2001, p. 161.

- ↑ Wrigley, Chris (ed.): Challenges of Labour. Central and Western Europe, 1917-1920, London 1993, pp. 4-5.

- ↑ Berta, Giuseppe: The Interregnum. Turin, Fiat and Industrial Conflict between War and Fascism, in: Wrigley (ed.), Challenges of Labour 1993, p. 107.

- ↑ Magraw, Roger: Paris 1917-20. Labour protest and popular politics, in: Wrigley (ed.), Challenges of Labour 1993, pp. 127-128.

- ↑ Gatrell, Russia’s First World War 2005, p. 70.

- ↑ Kocka, Facing Total War 1984, pp. 19-21.

- ↑ Gatrell, Russia’s First World War 2005, pp. 68-69; Waites, Bernard: A Class Society at War. England, 1914-1918, Leamington Spa 1987, pp. 120-122.

- ↑ Reid, Alastair: The Impact of the First World War on British Workers, in: Wall, Richard /Winter, J. M.(eds.): The Upheaval of War. Family, Work, and Welfare in Europe, 1914-1918, Cambridge 1988, pp. 225-227.

- ↑ Hautmann, Hans: Vienna. A City in the Years of Radical Change 1917-20, in Wrigley (ed.), Challenges of Labour 1993, p. 89.

- ↑ Fridenson, Patrick: The Impact of the First World War on French Workers, in: Wall/Winter (eds.), The Upheaval of War 1988, p. 239; Kocka, Facing Total War 1984, pp. 22-26; Wrigley (ed.), Challenges of Labour 1993, p. 7.

- ↑ Gatrell, Russia’s First World War 2005, p. 69.

- ↑ Wall/Winter (eds.): The Upheaval of War 1988, p. 36.

- ↑ Wrigley (ed.), Challenges of Labour 1993, pp. 89, 108-109, 129-130; Kocka, Facing Total War 1984, p. 26; Gatrell, Russia’s First World War 2005, p. 122.

- ↑ Magraw, Paris 1917-20 in Wrigley (ed.), Challenges of Labour 1993, p. 130.

- ↑ Wrigley (ed.), Challenges of Labour 1993, pp.31, 89-90; Kocka, Facing Total War 1984, p. 26.

- ↑ Daniel, Ute: Women’s Work in Industry and Family. Germany, 1914-18, in: Wall/Winter (eds.), The Upheaval of War 1988 p. 281.

- ↑ Gatrell, Russia’s First World War 2005, pp. 67-68.

- ↑ Magraw, Paris 1917-20 in Wrigley (ed.), Challenges of Labour 1993, pp. 127-130.

- ↑ Thom, Deborah: Women and Work in Wartime Britain, in: Wall/Winter (eds.): The Upheaval of War 1988, pp. 304-306; Culleton, Claire A.: Working-Class Culture, Women, and Britain, 1914-1921, New York 2000, p. 1.

- ↑ Sieder, Reinhard: Behind the Lines. Working-Class Family Life in Wartime Vienna, in Wall/Winter (eds.), The Upheaval of War 1988, pp. 117-119.

- ↑ Daniel, Women’s Work in Industry and Family in: Wall/Winter (eds.), The Upheaval of War 1988, pp. 276-277.

- ↑ Darrow, Margaret H.: French Women and the First World War. War Stories of the Home Front, Oxford 2000, p. 187.

- ↑ Darrow, French Women and the First World War 2000, pp. 214-215.

- ↑ Darrow, French Women and the First World War 2000, p. 215.

- ↑ Wall, Richard: English and German families and the First World War, 1914-1918, in: Wall/Winter (eds.), The Upheaval of War 1988, p. 61.

- ↑ Kennedy, David M.: Over Here. The First World War and American Society, Oxford 1981, p. 285.

- ↑ Berta, Giuseppe: The interregnum. Turin, Fiat and Industrial Conflict between War and Fascism, in Wrigley (ed.), Challenges of Labour 1993, pp. 107, 108-109.

- ↑ Proctor, Tammy: Civilians in a World at War, 1914-1918, New York 2010, pp. 41-42.

- ↑ Nogaro, Bertrand/Weil, Lucien: La Main-d’Oeuvre Etrangère et Coloniale Pendant la Guerre, Paris 1926, p. 25.

- ↑ Hill, Kimloan: Sacrifices, Sex, Race. Vietnamese experiences in the First World War, in: Santanu Das (ed.): Race, Empire and First World War Writing, Cambridge 2011, p. 55.

- ↑ Stovall, Tyler: Colour-blind France? Colonial Workers during the First World War, in: Race and Class 35/2 (1993), pp. 38-39.

- ↑ Hill, Sacrifices, Sex, Race in: Das (ed.), Race, Empire and First World War Writing 2011, p. 56.

- ↑ Stovall, Colour-blind France? 1993, p. 41.

- ↑ Stovall, Colour-blind France? 1993, pp. 43-44; Hill, Sacrifices, Sex, Race in: Das (ed.), Race, Empire and First World War Writing 2011, pp. 57-58.

- ↑ Connor, John S.: The Munitions Supply Company of Western Australia and the popular movement to manufacture artillery ammunition in the British Empire in the First World War, in: Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 39/5 (2011), pp. 798, 806.

- ↑ Connor, “The Munitions Supply Company of Western Australia” 2011, pp. 804-806.

- ↑ Proctor, Civilians in a World at War 2010, pp. 53-54.

- ↑ Proctor, Civilians in a World at War 2010, pp. 45-47.

- ↑ Proctor, Civilians in a World at War 2010, p. 55.

- ↑ Xu, Guoqi: Strangers on the Western Front. Chinese Laborers in the Great War, Cambridge, MA 2011, pp. 13-17, 27-29, 199-219.

- ↑ Xu, Strangers on the Western Front 2011, pp. 17-19, 27-29.

- ↑ Xu, Strangers on the Western Front 2011, pp. 55-79.

- ↑ Xu, Strangers on the Western Front 2011, p. 98.

- ↑ Xu, Strangers on the Western Front 2011, p. 89.

- ↑ Dendooven, Dominiek: Living Apart Together. Belgian Civilians and Non-White Troops and Workers in Wartime Flanders, in: Das (ed.), Race, Empire and First World War Writing 2011, pp. 150-152.

- ↑ Thiel, Jens: Between Recruitment and Forced Labour. The Radicalization of German Labour Policy in Occupied Belgium and Northern France, in: First World War Studies 4/1 (2013), pp. 41-42.

- ↑ Thiel, Between Recruitment and Forced Labour 2013, pp. 43-45.

- ↑ Westerhoff, Christian: ‘A Kind of Siberia’. German Labour and Occupation Policies in Poland and Lithuania during the First World War, in: First World War Studies 4/1 (2013), pp. 51-64.

- ↑ Gatrell, Russia’s First World War 2005, pp. 189-191.

- ↑ Thiel, Between Recruitment and Forced Labour 2013, p. 40.

- ↑ Reid, The Impact of the First World War on British Workers, in: Wall /Winter (eds.): The Upheaval of War 1988, p. 228.

- ↑ Godfrey, Capitalism at War 1987, pp. 106-143, 184-186.

- ↑ Hautmann, Vienna 1993, p. 89.

- ↑ Daniel, Women’s Work in Industry and Family in: Wall/Winter (eds.), The Upheaval of War 1988, pp. 267-268, 282-286.

- ↑ Horne, John: Labour at War. Britain and France, 1914-1918, Oxford 1991; Kennedy, Over Here 1981.

- ↑ Reid, The Impact of the First World War on British Workers, in: Wall /Winter (eds.): The Upheaval of War 1988, p. 227; Fridenson, p. 243.

- ↑ Sieder, Behind the Lines 1988, p. 125.

- ↑ Hautmann, Vienna 1993, pp. 92-93.

Selected Bibliography

- Connor, John S.: The war munitions supply company of western Australia and the popular movement to manufacture artillery ammunition in the British Empire in the First World War, in: The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 39/5, 2011, pp. 795-813.

- Culleton, Claire A.: Working class culture, women, and Britain, 1914-1921, New York 2000: St. Martin's Press.

- Darrow, Margaret H.: French women and the First World War. War stories of the home front, Oxford; New York 2000: Berg.

- Das, Santanu (ed.): Race, empire and First World War writing, Cambridge; New York 2011: Cambridge University Press.

- Dickinson, Frederick R.: War and national reinvention. Japan in the Great War, 1914-1919, Cambridge 1999: Harvard University Press.

- Feldman, Gerald D.: Army, industry, and labor in Germany, 1914-1918, Princeton 1966: Princeton University Press.

- Fridenson, Patrick (ed.): The French home front, 1914-1918, Providence 1992: Berg.

- Gatrell, Peter: Russia's First World War. A social and economic history, Harlow 2005: Pearson/Longman.

- Godfrey, John F.: Capitalism at war. Industrial policy and bureaucracy in France, 1914-1918, New York 1987: Berg; St. Martin's Press.

- Horne, John: Labour at war. France and Britain, 1914-1918, Oxford; New York 1991: Clarendon Press; Oxford University Press.

- Kennedy, David M.: Over here. The First World War and American society, New York 1980: Oxford University Press.

- Kocka, Jürgen: Facing total war. German society, 1914-1918, Cambridge 1984: Harvard University Press.

- Nogaro, Bertrand / Wiel, Lucien: La main-d'œuvre étrangère & coloniale pendant la guerre, Paris; New Haven 1926: Les Presses universitaires de France; Yale University Press.

- Proctor, Tammy M.: Civilians in a world at war, 1914-1918, New York 2010: New York University Press.

- Stovall, Tyler: Colour-blind France? Colonial workers during the First World War, in: Race & Class 35/2, 1993, pp. 33-55.

- Thiel, Jens: Between recruitment and forced labour. The radicalization of German labour policy in occupied Belgium and northern France, in: First World War Studies 4/1, 2013, pp. 39-50.

- Waites, Bernard: A class society at war, England, 1914-1918, Leamington Spa; New York 1987: Berg; St. Martin's Press.

- Wall, Richard / Winter, Jay (eds.): The upheaval of war. Family, work, and welfare in Europe, 1914-1918, Cambridge; New York 1988: Cambridge University Press.

- Westerhoff, Christian: ‘A kind of Siberia’. German labour and occupation policies in Poland and Lithuania during the First World War, in: First World War Studies 4/1, 2013, pp. 51-63.

- Wrigley, Chris (ed.): Challenges of labour. Central and western Europe, 1917-1920, London 1993: Routledge.

- Xu, Guoqi: Strangers on the Western Front. Chinese workers in the Great War, Cambridge 2011: Harvard University Press.