Background↑

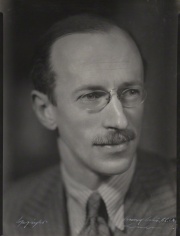

Basil Henry Liddell Hart (1895-1970), who first adopted "Liddell Hart" as his surname in 1921, served as an infantry officer on the Western Front. His historical significance lies, however, in his contribution as a journalist and historian in reshaping attitudes to the war in Britain during the late 1920s and early 1930s.

In the autumn of 1913 he began to read modern history at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, but at the outbreak of war he was caught up in the first wave of patriotic enthusiasm. He took a temporary commission in the University Officer Training Corps; and, in December 1914, he was gazetted as a Second-Lieutenant in the King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry. In mid-1915 he experienced the Western Front for the first time; during his second tour in the winter of 1915 in the Ypres salient he was concussed by an exploding shell and sent home. He returned to France in Spring 1916, but was gassed on 18 July in Mametz Wood during the Somme Offensive. For the remainder of the war, he served in home commands; he was promoted to Captain in April 1917.

Post-war Career↑

Liddell Hart began his career as a military writer after the war under the protective hand of two military patrons, Major-General Ivor Maxse (1862-1958) and Brigadier-General Winston Dugan (1876-1951). Parallel to his official duties, he began to write articles for military journals. As a result of his wartime injuries, and following receipt of a regular commission in 1921, two attempts to continue his military career, first with the Royal Army Educational Corps in 1921, then with the Royal Tank Corps in 1923, failed due to his medical record. He was placed on half-pay in 1923; he was officially discharged from military service in 1927. On 10 July 1925, he was able to launch his career as a journalist when he was appointed military correspondent for the Daily Telegraph. By the time he had left the army for good, he was already known as a military writer and journalist. It was during his time at the Daily Telegraph (which ended in March 1935 with his appointment as the Times military correspondent) that he most influenced attitudes towards the Great War.

Attitude towards the World War↑

In addition to the numerous articles he wrote, Liddell Hart’s impact upon attitudes towards the Great War came through several books, especially Reputations: Ten Years After (1928), The Real War 1914-1918 (1930), and Through the Fog of War (1937), although many of his books were simply collections of his newspaper articles. There were contradictions in Liddell Hart’s view of the war, exemplified by his dedication to John Buchan (1875-1940) as "My First Guide and Friend in Literature" in The British Way in Warfare (1932); Buchan was the best representative of uncritical, patriotic historical writing on the war in the immediate post-war period. Liddell Hart’s judgements of commanders were more critical and tinged with pacifism, although he retained a certain deference towards those he criticised. In The Real War, he contributed to a shift in opinion from adulation of commanders towards a more realistic view of the performance of the British army, especially in the Third Ypres Offensive of 1917. His writing on military theory, most notably his concept of "the indirect approach", espoused in his book The Decisive Wars of History (1929), was influenced by his experience of the Western Front. He devoted much of his writing before 1940 to arguing for positions which he thought would prevent a repeat of the casualties of 1914-1918, such as the argument that Britain should concentrate on its navy and avoid a war on the European continent, although paradoxically he was also an enthusiastic supporter of mechanization.

Later Life↑

Due to his claim in the late 1930s that the defensive was stronger than the offensive in land warfare, Liddell Hart fell out of favour after the fall of France in June 1940. He spent the rest of the war in relative obscurity, working mainly as a journalist. He did also produce some interesting books in this period. After the Second World War, he was able to rescue his reputation as a military commentator, in part through his advocacy of West German rearmament and through historical studies such as his History of the Second World War (1970). His continuing interest in the First World War was demonstrated in Volume I of his history of the Royal Tank Regiment, The Tanks (1959).

Alaric Searle, University of Salford

Section Editor: Jennifer Wellington

Selected Bibliography

- Bond, Brian: Liddell Hart. A study of his military thought, London 1977: Cassell.

- Bond, Brian (ed.): The First World War and British military history, Oxford; New York 1991: Clarendon Press; Oxford University Press.

- Danchev, Alex: Alchemist of war. The life of Basil Liddell Hart, London 1998: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

- Liddell Hart, Basil Henry: A history of the world war, 1914-1918, London 1934: Faber & Faber.

- Liddell Hart, Basil Henry: The real war, 1914-1918, London 1930: Faber & Faber.

- Mearsheimer, John J.: Liddell Hart and the weight of history, Ithaca 1988: Cornell University Press.