From Scholar to Soldier↑

Thomas Edward (T.E.) Lawrence (1888-1935) was born out of wedlock to a member of the Anglo-Irish aristocracy and the family nurse. Many accounts of his remarkable life have stressed his illegitimate birth as the driving force behind his wartime exploits and the fame and glory that they brought. However, he also joined the Arab Bureau in Cairo well prepared for its work by an excellent Oxford education that included a 1,600 kilometer tour on foot of the Levant while researching what was to be a prize-winning thesis on Crusader Castles in 1909. Archaeological work gave him fluency in colloquial Arabic and a familiarity with the people of the rural, and then still tribal, hinterlands of the Levant and Northern Iraq. Once the First World War broke out, this background proved crucial, especially after Lawrence was transferred to military intelligence in Cairo in the fall of 1914.

Into Battle: The Arab Campaign↑

Lawrence’s first foray into the battlefields of the Middle East came in April 1916 as part of an abortive mission to bribe the commander of the Ottoman forces besieging Kut. However, Lawrence’s real impact on the course of the war came after he was transferred to the Arab Bureau in late 1916 and went on a mission to the Hejaz to assess the status of the Arab Revolt and determine the causes of its slow progress north after the capture of Rabegh and Yanbu. Lawrence attached himself to the staff of Faysal I, King of Iraq (1885-1933), the commander of the northern armies of the Arab Revolt, becoming his official advisor in December 1916. Lawrence took credit for pushing Faysal to advance into Syria, where the forces of the revolt could operate among a population sympathetic to Arabism, and on the eastern flank of British forces advancing into Palestine in 1917-1918. Arab sources in particular have questioned this account, pointing out that a move into Syria had in any case been the strategy of Faysal, who had made contact with the Arab secret societies in Damascus as early as 1915. Lawrence was at the time little more than a junior liaison officer – albeit one who commanded considerable amounts of gold and military supplies, resources that were, far more than nationalism, the real currency of the revolt.

Whatever the truth of these competing claims, Lawrence’s post-war writings (and those of sympathetic military historians) propagated a view of the Arab Revolt as a successful guerilla campaign and an exemplary application of the strategy of the “indirect approach.” On this account, the capture of Aqaba in July 1917 was achieved by means of an assault from the landed side of the Red Sea port, after a circuitous advance through the Wadi Sirhan had achieved complete strategic surprise. The bombings of the trains and culverts of the Hejaz railway were undertaken to bleed the Ottoman army, disrupting its extended supply lines without cutting them, while all the time diverting men and materials from the main confrontation in Palestine. Recent archaeological research supports claims that the Arab Revolt may have diverted as many as 40,000 Ottoman troops from the front lines in Palestine, while the nationalist sentiment that it fomented in Syria and Iraq undermined the Ottoman war effort further by encouraging the desertion of hundreds of thousands of Arab conscripts. Yet Lawrence himself described the Arab Revolt as a “sideshow of a sideshow.” Lawrence acknowledged that his attempt to relieve Edmund Allenby (1861-1936) by destroying the railway bridges at Deraa in October 1917 ended in failure. The Arabs were unable to extend significant support to the two unsuccessful Trans-Jordan raids that were mounted on Ottoman positions in the Balqa’ in the spring of 1918. It was only the Turkish collapse after Allenby’s victory at Megiddo that opened the way for the forces of the revolt to enter Damascus on 1 October 1918 – and even there, they were preceded into the city by Australian troops.

War’s Aftermath: Sharifian Solution and Obscurity↑

Lawrence played an important role in gaining British support for the Arab government established under Faysal in Damascus at the end of the war. He then appeared as a key advisor to Faysal during the Peace Conference at Versailles in February 1919. Even after the division of the Fertile Crescent between Britain and France and the expulsion of Faysal from Damascus in August 1920, Lawrence continued to campaign for greater Arab independence. He quite consciously exploited his wartime repute to call for a pattern of mandate government in which local rulers played a leading part. This “Lawrencian” approach proved attractive to Whitehall once imperial overstretch and the costs of putting down the June-October 1920 uprising in Iraq recommended a resort to more cost-effective methods in the areas left under British control after St. Remo (1920).

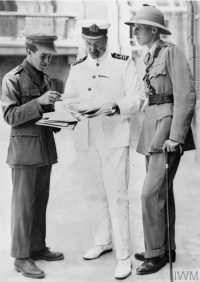

Lawrence emerged as the most influential advisor in the newly established Middle East Department after joining Winston Churchill (1874-1965) in the Colonial Office in February 1921 as an adviser. At the Cairo Conference convened in March of the same year, Lawrence was instrumental in implementing a ‘Sharifian solution’ that installed Faysal and his older brother, Abdullah, King of Jordan (1882-1951) as, respectively, the rulers of Iraq and Trans-Jordan (where Lawrence served as Chief British Representative for the last three months of 1921) under British tutelage. On his last official mission to the Middle East in early 1922, Lawrence tried in vain to induce Husayn ibn Ali, King of Hejaz (c.1853-1931) to recognize Britain’s Mandate in Palestine in return for a treaty with Britain that would protect his Hashemite of the Hejaz from the looming threat of Wahhabism.

After leaving the Colonial Office in July 1922, Lawrence withdrew from the public eye, serving under assumed names in the Tank Corps and the Royal Air Force (RAF). He was killed in a motorcycle accident in 1935 shortly after being discharged from the armed forces. The scale of the state funeral in which he was laid to rest, and the status of those who attended it, testified to his hold on the popular imagination. Thick layers of “Lawrenciana” have continued to accumulate around his name ever since, making it difficult to reach a balanced historical judgment of his wartime exploits or of his influence on the post-war Middle East.

Tariq Tell, American University of Beirut

Selected Bibliography

- Anderson, Scott: Lawrence in Arabia. War, deceit, imperial folly and the making of the modern Middle East, London 2014: Atlantic Books.

- Faulkner, Neil: Lawrence of Arabia's war. The Arabs, the British and the remaking of the Middle East in WWI, New Haven 2016: Yale University Press.

- Mack, John E.: A prince of our disorder. The life of T. E. Lawrence, London 1976: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

- Mūsá, Sulaymān: T. E. Lawrence. An Arab view, London; New York 1966: Oxford University Press.

- Wilson, Jeremy: Lawrence of Arabia. The authorized biography of T. E. Lawrence, London 1989: Heinemann.