Introduction↑

It is fair to say that Britain’s Royal Air Force (RAF), officially born on 1 April 1918, owed its origins to wartime exigencies, public pressure, supply difficulties, the competition for resources, and the advocacy of airpower visionaries. Combining the overlapping functions of the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS), it became the world’s first independent air arm and eventually led to profound changes in airpower organization, theory, and doctrine around the world. Not surprisingly, perhaps, the earliest moments of the RAF’s existence were marked by turmoil, bureaucratic confusion, and rapid changes of leadership. That these challenges were overcome and by the end of World War I the RAF had become the world’s largest air service – with approximately 300,000 officers and airmen and more than 22,000 aircraft – is a tribute to the vision and commitment of its creators.

↑

Responding, in part, to a small but vibrant group of aeronautical enthusiasts, British military aviation began in 1911, some eight years after the Wright brothers’ first flight. British army engineers formed an air battalion of aircraft, airships, and balloons. This tiny unit eventually became the RFC. The Royal Navy followed three years later with a naval wing, recognized in July 1914 as the RNAS. It was strongly supported by Winston Churchill (1874-1965) as First Lord of the Admiralty. Accordingly, the outbreak of World War I saw two relatively independent British air forces. The RFC’s location and responsibility was in France and Belgium. Its principal mission was to provide reconnaissance to the army. The RNAS was based in Britain and was supposed to provide air defense. Given its youth, its role in naval operations was less clearly defined.

Inefficacy of British Aviation↑

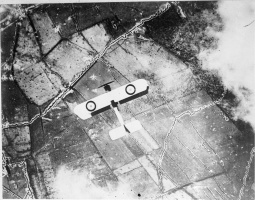

Events of the war led to dramatic changes in the evolution and impact of airpower over land and sea. RFC reconnaissance and artillery spotting missions over the frontlines in France led quickly to fighter combat and the development of the air superiority and tactical ground support missions. The RNAS championed long-range bombing, carrier-born operations, aerial torpedo attacks, and anti-submarine warfare. But Germany pioneered the introduction of strategic bombardment. Even if the physical impact was severely limited by technology, by employing zeppelins in 1915 and 1916, and a year later long-range bombers to attack London, the Germans nevertheless outraged the British public. The attacks and resulting civilian casualties led to calls for revenge and a justifiable frustration at Britain’s own capabilities.

This factor, along with the increasing demand for the most up-to-date aircraft, experienced pilots and crewmen, maintenance personnel, and the supply of other severely strained resources quickly made it apparent that Britain’s two competing aviation bureaucracies were inefficient and damaging the overall war effort. Simply put, when it came to airpower, the War Office and the Admiralty were unable to cooperate sufficiently. As a result, in the summer of 1917 the government directed British army General Jan Christian Smuts (1870-1950) to examine British air defense and the overall organization of air operations. Brilliantly supported by Sir David Henderson (1862-1921), the first commander of the RFC in France, Smuts produced a document often referred to as the “Magna Carta” of airpower. In a remarkable sequence of events, this study, which called for a unified and independent air force, was carried out and presented in only eight days. Given the circumstances, it was immediately accepted by the government.

Conclusion↑

After a very short period of turmoil, marked by a succession of dramatic and controversial senior personnel changes, the Royal Air Force was established and led by an Air Ministry. Lord William Weir (1877-1959) became Secretary of State for Air and Major General Sir Frederick Sykes (1877-1954) became the Chief of the Air Staff. Despite the agitation and initial confusion, the brand new Royal Air Force successfully met the challenges occasioned by the German spring offensives of 1918 and subsequent months of campaigning. It fought effectively and eventually took the war to Germany. By any measure the RAF contributed to Germany’s defeat and justified its formation. In the context of history, it has served as a prototype for independent air forces world-wide.

Mark Wells, United States Air Force Academy

Section Editor: Mark E. Grotelueschen

Selected Bibliography

- Cox, Sebastian / Gray, Peter W. (eds.): Air power history. Turning points from Kitty Hawk to Kosovo, London; Portland 2002: Frank Cass.

- Lawson, Eric / Lawson, Jane: The first air campaign, August 1914-November 1918, Conshohocken 1996: Combined Books.

- Morrow, Jr., John Howard: The Great War in the air. Military aviation from 1909 to 1921, Washington, D.C. 1993: Smithsonian Institution Press.

- Wells, Mark K. (ed.): Air power. Promise and reality, Chicago 2000: Imprint Publications.