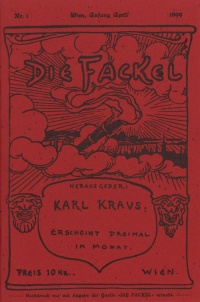

Before the War: The Torch, 1899–1914↑

Born in Bohemia, Karl Kraus (1874-1936) spent the majority of his life in Vienna. He started out his literary career in theater and was affiliated with the literary group Young Vienna before breaking off in 1897. Two years later, Kraus founded his own satirical journal, entitled Die Fackel (The Torch), which he published frequently but irregularly until his death in 1936. For the first eleven years of its circulation, Die Fackel included contributions from various personalities that comprised fin-de-siècle Germany and Austria. From 1911 onward, Kraus assumed sole authorship of the journal.

Kraus ridiculed some of the leading literary and journalistic figures of the day for what he perceived to be their criminal abuses of language. Among these figures were Hermann Bahr (1863–1934), the unofficial spokesman of Young Vienna, and Moriz Benedikt (1849–1920), the proprietor of the Neue Freie Presse (New Free Press), Austria-Hungary’s most influential newspaper and the mouthpiece of the Social Democrats. Though Kraus despised the nationalist right and their press organs, he directed the majority of his satire at the liberal press, since it was there where he saw deceit and hypocrisy at their most pervasive.

During and after the War↑

"In These Great Times"↑

Kraus fell silent for the first six months of the war until publishing "In dieser großen Zeit" ("In These Great Times") in December 1914. This essay excoriated the press for producing a language that diminished its readers’ capacities to imagine a world in which war was not possible. This was Kraus’s primary critique: that while its ostensible purpose was to inform the public, the press instead thought for, and thereby exerted control over the public. Kraus believed that modern Europe had become alienated from its own humanity, the domination of the press over the imagination serving as the most salient example of this phenomenon.

The Last Days of Mankind: 1915–1922↑

From 1915 to 1922, Kraus wrote his magnum opus, Die letzten Tage der Menschheit. Tragödie in fünf Akten mit Vorspiel und Epilog (The Last Days of Mankind: Tragedy in Five Acts with Prologue and Epilogue), a dramatic lampoon of the First World War. Half of the drama’s dialogue consists of actual quotations from newspapers or conversations that Kraus overheard on the streets of Vienna. Kraus employed quotation to a highly effective degree, believing that as a satirist, his primary charge was to reproduce the violent and obscene language that informed and perpetuated the war.

The drama adheres to certain conventions of classical tragedy, but in its use of montage, photography, expressionist, and cinematic elements, it could be considered a work of modernism. Allegedly suitable only for a “theater on Mars” (the god of war),[1] the drama stages a cacophonous arrangement of propaganda and journalistic taglines, in which the historical and the fictional collide. Generals, editors, writers, artists, politicians, statesmen, soldiers, doctors, popes, subscribers, and patriots all make appearances, and none is spared satirical treatment. All of them, for Kraus, shouldered responsibility for the war.

The running dialogue between the “Grumbler” (Kraus’s alter ego) and the “Optimist” lends the drama a sense of unity. In these exchanges, the Optimist usually presents his interlocutor with a moderate to right-wing proposition regarding the war’s developments, only to have it exposed as internally unsustainable by the Grumbler. The Grumbler thus shows himself to be less a moralizing figure than a dialectician who envisions the war as an apocalyptic event.

Kraus’s fear of an endless catastrophe proved prescient. In 1934 he supported the Austro-Fascist Engelbert Dollfuss (1892–1934), whom he believed to be the last bulwark against the National Socialists. This decision estranged Kraus from many of his admirers in the radical left, among them Walter Benjamin (1892–1940) and Bertolt Brecht (1898–1956). Kraus died a relatively unpopular figure in 1936.

Ari Linden, University of Kansas

Section Editor: Frederik Schulze

Notes

- ↑ Kraus, Karl: The Last Days of Mankind, in: Zohn, Harry (ed.): In These Great Times. A Karl Kraus Reader, Chicago 1990, p. 159.

Selected Bibliography

- Kraus, Karl, Benjamin, Walter / Goldmann, Lucien; Hatvany, Paul et al. (eds.): Karl Kraus, Paris 1975: Ed. de l'Herne.

- Kraus, Karl: Die letzten Tage der Menschheit. Tragödie in fünf Akten mit Vorspiel und Epilog, Munich 1964: Dt. Taschenbuch-Verlag.

- Perloff, Marjorie: Avant-garde in a different key. Karl Kraus's the last days of mankind, in: Critical Inquiry 40/2, 2014, pp. 311-338.

- Timms, Edward: Karl Kraus, apocalyptic satirist. The post-war crisis and the rise of the swastika, New Haven 2005: Yale University Press.

- Timms, Edward: Karl Kraus, apocalyptic satirist. Culture and catastrophe in Habsburg Vienna, New Haven 1986: Yale University Press.