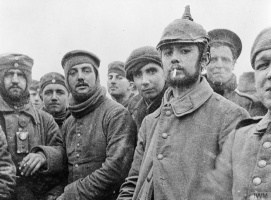

Christmas 1914↑

On Christmas 1914, several truces were declared between armies that had been fighting a deadly war for several months along different parts of the front. Soldiers - for the most part conscripts and volunteers - were far from their loved ones and subjected to the harsh conditions of trench life. They had to contend with a lasting war and the reality of daily casualties, weather conditions, arduous battles to correct positions and deadly attacks to attempt to break through enemy lines. Christmas was a celebration shared by both sides and recalled for both the comforts of home and a desire for peace. From trench to trench, men called out and threw each other newspapers, tobacco and food. They challenged each other with rounds of songs and shared traditional Christmas carols. German, French and British soldiers’ accounts mention actual encounters in no man’s land, including some impromptu football matches. These Christmas truces were particularly covered in the British and German press.

Broader Context↑

The Christmas truces appear to fit into the broader context of movements to limit the violence of war, as historian Tony Ashworth has notably shown regarding the British front throughout the war. A system of “live and let live” existed between enemy trenches at several periods and in several sectors along the front. Such fraternization was also a form of both individual and collective disobedience towards military authority and allowed soldiers to conceive of the enemy as a comrade. Several French, German and English-speaking historians have pointed to attempts by soldier-citizens to exercise their right to contest. Despite depersonalization and feelings of animosity that likely fuelled the violence of trench warfare, cases of fraternization including the Christmas truces underscore the ability of soldiers to assess the relevance of the war and, in some cases, to deem fraternization more legitimate. And yet such behaviour was nonetheless kept in check by the social and military norms of war, the high degree of supervision (particularly in the Italian army, for example) and feelings of anger directed at the enemy, all of which were reinforced by military strategies to perpetuate the combativeness of men.

Alexandre Lafon, Université de Toulouse 2 – Jean-Jaurès

Section Editor: Emmanuelle Cronier

Translator: Jocelyne Serveau

Selected Bibliography

- Ashworth, Tony: Trench warfare 1914-1918. The live and let live system, New York 1980: Holmes & Meier.

- Barthas, Louis, Cazals, Rémy (ed.): Les carnets de guerre de Louis Barthas, tonnelier (1914-1918), Paris 1978: F. Maspéro.

- Bourke, Joanna: An intimate history of killing. Face-to-face killing in twentieth-century warfare, New York 1999: Basic Books.

- Ferro, Marc (ed.): Frères de tranchées, Paris 2005: Perrin.

- Loez, André: Fraternisations: Les 100 mots de la Grande Guerre, Paris 2013: Presses universitaires de France, pp. 58-59.

- Watson, Alexander: Enduring the Great War. Combat, morale and collapse in the German and British armies, 1914-1918, Cambridge; New York 2008: Cambridge University Press.