Introduction↑

The United States did not enter the Great War until 1917 and suffered far fewer casualties than other belligerents. President Woodrow Wilson (1856-1924) unprecedentedly, travelled to Europe to participate in peace talks and defined hope for a stable future through his liberal vision of collective security brought about by a League of Nations. Ultimately, the US failed to join the League and remained detached from the European political system. Still, a strong American presence developed in the “Old World.” One of the most powerful representations of the US abroad came from the monuments and cemeteries erected in European lands. Throughout the interwar years, even during the Great Depression, the government of the United States finalized its expansive World War I commemorative projects in Europe. Considerable numbers of American citizens travelled to see these sites of memory abroad.

The Great War, and its memory, are ever present in European society today. By contrast, World War I has a far more ambivalent place in the US. It was a war without clear goals, its peace tainted by disillusionment and it was eventually overshadowed by World War II. The central questions asked by American scholars who study the memory of World War I are, “Does the Great War have a place in American collective memory?” and, “Is the American memory of World War I distinguishable from World War II?”[1]

Burial and Repatriation of War Dead↑

Americans understood that significant numbers of military personnel would die in Europe once their country entered the Great War. However, most expected the return of dead for burial in home soil. This was the precedent established in the Spanish-American War, the Filipino Insurrection and the Boxer Rebellion. Secretary of War Newton D. Baker (1871-1937) strengthened this expectation after publicly promising at the onset of the war that all American dead from the Western Front would come home.[2] The logistics of war trumped personal wishes, however. American war dead became a problem for the high command. Precious cargo space for war materials could not be sacrificed for corpses, caskets and burial equipment at the height of massive US offensives. Shortly after arriving in Europe the commander of the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF), General John J. Pershing (1860-1948), ordered all US casualties to be interred near battlefields until hostilities had ended.[3]

The actions of the French and American governments made the return of corpses even more indefinite following the November 1918 Armistice. The French government passed a law prohibiting all exhumations of war dead from its soil for three years, beginning in 1919. This action was based on practical necessity. France estimated that nearly 5 million dead were in its soil. Quick repatriation of all of these dead would stunt France’s reconstruction from war and further the emotional depression of the French people. French Marshal Philippe Pétain (1856-1951) hoped that Americans would leave their dead in the soil of their historic ally. He assured Pershing of France’s desire to honor American victims on her soil.[4] Pershing saw that Allied nations were already establishing military cemeteries and monuments on the Western Front. He feared that the complete removal of US military remains would erase the memory of American sacrifice for Europe from the continent. Shortly after the war he cabled the War Department in Washington, DC and opined that if American dead “could speak for themselves, they would wish to be left undisturbed with their comrades.”[5] He subsequently tasked members of his personal staff with formulating a plan to effectively commemorate the sacrifices of the AEF. At the same time, the US Congress began debating the cost efficiency of total repatriation versus overseas commemoration.

The American public divided sharply on what should happen with its war dead abroad. Prominent Americans like General Pershing and Theodore Roosevelt (1858-1919) argued that soldiers should rest where they fell. Roosevelt himself chose to leave the body of his son Quentin, a deceased combat pilot, buried in France. Other Americans expected the US government to fulfil its promise and return their dead home. Groups like the "Bring Home Our Soldier Dead League" formed to lobby the government to transfer corpses back to the United States. Americans opposed to leaving remains in France often feared that the French only saw US cemeteries as a means to generate revenue through tourism. In the end, a mixed repatriation policy was adopted. American next-of-kin were given the choice between repatriation and an overseas burial. Secretary of State Robert Lansing (1864-1928) convinced the French government to allow US repatriations to take place prior to the three-year exhumation ban’s end.

As Americans made repatriation decisions, the Graves Registration Service chose ideal sites for permanent US military cemeteries in Europe. Of the approximately 116,000 US dead in World War I, 30,922 (roughly 37 percent) were interred in eight permanent cemeteries located in France, Belgium, and England.[6] In 1923, the United States Congress established the American Battle Monuments Commission (ABMC) to maintain all US World War I monuments and military cemeteries abroad.

Gold Star Pilgrimages↑

The American government desired the military cemeteries and monuments it erected in Europe to be filled with mourners. While much care went into creating aesthetically powerful sites of memory, they alone were not enough to impart feelings of American sacrifice to foreigners.[7] It was the presence of the living that added something extra to these sites. Grieving American women, called Gold Star Mothers and Wives, provided the most tangible examples of US sacrifice. From 1930 through 1933, contingents of American female mourners arrived in France on federally sponsored pilgrimages. At a cost of over 5 million dollars, approximately 7,000 American mothers and widows traveled to Europe to visit the graves of the dead they relinquished to their government.[8] These Gold Star Mother pilgrimages stand out in US history. After no other American military conflict, including World War II, did the federal government take on the financial burden of sending mourners to the graves of their kin. The pilgrimages also happened during the height of the Great Depression. This was indicative of the importance that American society placed on catering to the needs of its grieving women. In this nascent period of female suffrage, American women effectively mobilized their political power to ensure their pilgrimages took place.

Historians have analyzed the Gold Star pilgrimages primarily through the lenses of gender and race. At their most basic level, the pilgrimages highlight stereotypical 20th century perceptions of female fragility and need for masculine care. Notions that grieving women, not men, deserved a pilgrimage to graves abroad showed the perceived delicacy of their sex and the primordial nature of a mother’s love. Male leaders in Washington planned for the female pilgrim’s care at every step. Invitations went to the women deemed eligible by the government, their travel was taken care of and the month-long trip took place in luxury that the majority of women had never experienced. Each pilgrim also had access to a team of nurses and guided tours by Army officers. American Gold Star Mothers received vigilant care but certainly were not complacent in the pilgrimage process. Female mourners did not merely require pilgrimages for closure more than men but they effectively argued that maternal loss garnered a “privileged status,” deserving more empathy than sacrifices made by fathers or even widows in some instances.[9]

Race also played a visible role in the Gold Star pilgrimages. The American Battle and Monuments Commission (ABMC) adopted desegregated burial practices but American women visited graves under the prevailing customs of Jim Crow. Congress ultimately decided that white pilgrims and black pilgrims should not travel together but promised African Americans that “no discrimination whatsoever” would be made and that “each group would receive equal accommodations, care, and consideration.”[10] Segregation was primarily justified by the cultural inability of American passenger ships to accommodate both races equally on the same voyage. African Americans did receive hospitable treatment throughout their voyages but it was far from equal. They traveled on less luxurious vessels, were kept off of white train cars in France (American policy), assigned special black nurses and guides and inundated with white American typecasts - like being greeted by black jazz musicians and fed meals of fried chicken and imported watermelon.[11] Of the approximately 1,600 African American women possibly eligible for the trip, only a few hundred received invitations to travel abroad.[12] Of the select few, not all made the segregated pilgrimage, in part because the National Association for Colored People urged women to boycott in protest of federally-sponsored racial segregation. Between 1930 and 1931, 168 African American mothers participated in the pilgrimages compared to 5,251 white mothers.[13]

The Gold Star pilgrimages also functioned as missions of public diplomacy. Part of the American government’s intent with the pilgrimages was to place mourning women on Europe’s soil. Grieving women engaging with American sites of memory in France improved the image of the United States. American dead demanded continued Franco-American respect despite the rise of anti-Americanism, economic depression and growing militant nationalism that increased in Europe through the interwar period. Republican New York Congressman Fiorello LaGuardia (1882-1947), was instrumental in obtaining funding for these pilgrimages. He envisioned the trips not just as a mission “to give mothers relief [...] but to do a great deal for world peace.”[14] Ultimately, La Guardia felt that the pilgrimages might show that the “companionship of sorrow is more enduring than the comradeship of victory.”[15] For three years, the French saw a continuous flow of American women among them. They stood out among the crowd: wearing purple arm bands monographed with “pilgrim,” riding in large touring buses and following uniformed officers. The presence of American women signified that the United States really had not forgotten the commitments it had promised.

Private and Public Mourning↑

Jay Winter stressed in his groundbreaking Sites of Memory, Sites of Mourning that historians overemphasize the political character of war commemoration.[16] According to Winter, political studies are useful for improving our general understanding of the symbolic exchanges between the living and the dead; however, overstating the politics of these places erases their true historical meaning. Nations, communities, and individuals erected such sites of memory for mourning. Above all else, they served as places the grieving could visit and confront the “brutal facts of death in war.”[17] This is certainly true in both Europe and the United States. However, the mourning that Europeans experienced in the aftermath of World War I was infinitely greater than that of the United States. Essentially no household in Europe escaped loss in the Great War. Monuments saturated the landscape from the most remote locales to the national level. Additionally, the killing fields of the Western Front were easily accessible to European mourners.

The American mourning experience was very different. American deaths took place an ocean away. The public fracture over repatriation of overseas burials was representative of a fissure in the way America collectively remembered the war. Local communities throughout the United States erected doughboy monuments to mourn their losses, much like Europe. The piecemeal return of bodies prevented a unified memory from being established for Americans at home, however. Other than Arlington National Cemetery, no other grand World War I cemetery existed. American bodies often returned home to their family grave plots, diluting a national memory. The only federally commissioned memorial to the Great War in the US is a small park on the National Mall named Pershing Park. It commemorates the sacrifices of the AEF but is just as much a memorial to their commander. Monuments to World War I exist throughout the United States but to truly understand the country’s commemorative goals, one needs to look to Europe and the work of the ABMC. This form of federally funded public mourning greatly overshadows the efforts of private mourning in the United States.

The ABMC that evolved from Pershing’s Battle Board in 1923 was an organization with a clear commemorative vision. Chaired by General Pershing himself, the ABMC adopted somewhat draconian measures. The federal government seemed ever-present in the lives of Americans after the First World War. In the Congressional hearings to establish the ABMC, congressmen insisted on the government’s obligation to commemorate in the modern era. One congressman stated that “the public should not be bothered” about erecting monuments because it was now “clearly the duty of the Government to erect suitable memorials to its soldiers.”[18] Leadership in the ABMC spent considerable time touring American Civil War battlefields at Antietam and Gettysburg to develop a clear vision of how its World War I battlefields on the Western Front should be commemorated. They ultimately concluded that American Civil War battlefields lacked a cohesive memory and narrative because they were inundated with private memorials. The ABMC saw this same practice happening in Europe. In the immediate aftermath of the war, American units erected crude monuments to commemorate their action. This practice only continued for a short time. Once the ABMC was established, a formal agreement was struck with the French government not to allow any US memorials to be placed on French soil without ABMC approval. The ABMC would create the official memory of American sacrifice on European soil and determine what private monuments already placed would stay or be removed.

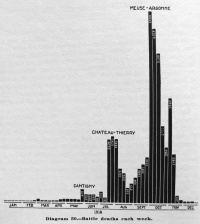

The ABMC created a multi-faceted commemorative plan. It erected several large monuments to commemorate large US battles such as Belleau Wood, Château-Thierry, St. Mihiel, and the Meuse-Argonne. It also staffed a historical team to write the official histories of AEF divisional service in World War I and an accurate guidebook for American tourists visiting their World War I battlefields. The most important element of the ABMC’s commemorative work was, by far, its eight cemeteries. These sacred locations would offer concrete symbols of American sacrifice as defined by the ABMC. Some of the most predominant symbols chosen by the ABMC for its cemeteries were: Judeo-Christian sacrifice, racial equality, social equality, democratic soldiery and the power of the federal government. Many of these, primarily Judeo-Christian themes and perceptions of racial equality, were not reflective of the realities of American society. The heavy-handed tactics of the ABMC created a unified but controversial memory of American sacrifice for Europe. French towns frequently became upset when the ABMC removed monuments erected by small units; American veterans’ groups sometimes felt closed off from their own memories; and segments of the American public felt the ABMC’s memory was unrepresentative of the real United States.[19] The Second World War began not long after the ABMC’s World War I work was completed. This brought a new wave of commemoration and a lull in critiques of the ABMC’s World War I work.

Conclusion↑

The public commemoration led by the ABMC greatly (and intentionally) overshadowed private American commemorative efforts after World War I. Understanding American World War I memory is not possible without an understanding of government commemorative motives. The United States entered the world stage in World War I but failed to become fully invested in European politics in the war’s aftermath. In the absence of a strong American presence overseas, its memory of sacrifice in World War I became a way for the US to project its commitment to Europe. America’s World War I sites of memory in Europe became locations for leaders, and citizens, in France and the US to reiterate their commitments to one another. Through the turbulent interwar years, ABMC monuments became places to allay anti-Americanism and call for international peace. The ABMC’s commemorative projects were completed just years before World War II. Following that war, the ABMC’s scope and mission only expanded.

Richard Allen Hulver, West Virginia University

Section Editor: Edward G. Lengel

Notes

- ↑ Trout, Stephen: On the Battlefield of Memory: The First World War and American Remembrance, 1919-1941, Tuscaloosa 2010; Budreau, Lisa: Bodies of War: World War I and the Politics of Commemoration in America, 1919-1933, New York 2010; Snell, Mark (ed.): Unknown Soldiers: The American Expeditionary Forces in Memory and Remembrance, Kent 2008; and Piehler, Kurt: Remembering War the American Way, Washington, DC 1995.

- ↑ Hayes, Ralph: Care of the Fallen: A Report to the Secretary of War on American Military Dead Overseas, Washington, DC 1920, p. 11. See also Budreau, Bodies of War 2010, p. 21.

- ↑ Hayes, Care of the Fallen 1920, p. 20.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 23.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 24.

- ↑ See www.ABMC.gov. Accessed on 10 March 2015.

- ↑ See Robin, Ron: Enclaves of America: The Rhetoric of American Political Architecture Abroad, 1900-1965, Princeton 1992.

- ↑ Budreau, Bodies of War 2010, p. 207.

- ↑ Budreau, Lisa: The Politics of Remembrance: The Gold Star Mothers’ Pilgrimage and America’s Fading Memory of the Great War, in: The Journal of Military History, 72/2 (2008), p. 393. Mothers and widows (who did not remarry) received top priority. Remarried widows were completely disqualified.

- ↑ Budreau, Politics of Remembrance 2008, p. 401.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 400. Also see Gold Star Negroes Welcomed in Paris. In: The New York Times, 22 July 1930 in Proquest Historical Newspapers.

- ↑ Budreau, Bodies of War 2010, p. 211.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 215.

- ↑ LaGuardia, Fiorello: Hearing Before A Subcommittee of the Committee on Military Affairs United States Senate, Seventieth Congress, First Session, on H.R. 5494, Bill to Enable the Mothers and Unmarried Widows of the Deceased Soldiers, Sailors, and Marines of the American Forces Interred in the Cemeteries of Europe to Make a Pilgrimage to these Cemeteries, May 14 1928, Part I & II, Washington, DC 1928, Part I, pp. 13-14.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Winter, Jay: Sites of Memory, Sites of Mourning, New York 1996, p. 93.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Sentiments of Stephen G. Porter, House Chairman of Committee on Foreign Affairs, in: American Battle Monuments Commission: Hearings Before the Committee on Foreign Affairs, House of Representatives, Sixty-Seventh Congress, Second and Third Sessions on H.R. 9634 and H.R. 10801, March 15-20, November 28, December 7-9, 1922, Washington, D.C. 1922, pp. 10-11.

- ↑ French Group Resists Pershing on Memorial. In: The New York Times, 12 August 1930 in Proquest Historic Newspapers. And, Robin, Enclaves 1992, pp. 57-60.

Selected Bibliography

- American Battle Monuments Commission (ed.): American armies and battlefields in Europe. A history, guide, and reference book, Washington, D.C. 1938: United States Government Printing Office.

- Blower, Brooke Lindy: Becoming Americans in Paris. Transatlantic politics and culture between the World Wars, Oxford; New York 2011: Oxford University Press.

- Budreau, Lisa M.: Bodies of war. World War I and the politics of commemoration in America, 1919-1933, New York 2010: New York University Press.

- Costigliola, Frank: Awkward dominion. American political, economic, and cultural relations with Europe, 1919-1933, Ithaca 1984: Cornell University Press.

- Hayes, Ralph A.: A report to the Secretary of War on American military dead overseas, Washington, D.C. 1920: Government Printing Office.

- Laderman, Gary: The sacred remains. American attitudes toward death, 1799-1883, New Haven 1996: Yale University Press.

- Piehler, G. Kurt: Remembering war. The American way, Washington, D.C. 1995: Smithsonian Institution Press.

- Robin, Ron Theodore: Enclaves of America. The rhetoric of American political architecture abroad, 1900-1965, Princeton 1992: Princeton University Press.

- Roger, Philippe: The American enemy. A story of French anti-Americanism, Chicago 2005: University of Chicago Press.

- Sledge, Michael: Soldier dead. How we recover, identify, bury, and honor our military fallen, New York 2005: Columbia University Press.

- Snell, Mark A. (ed.): Unknown soldiers. The American Expeditionary Forces in memory and remembrance, Kent 2008: Kent State University Press.

- Todd, Lisa M.: The politics of remembrance. The Gold Star Mothers' pilgrimage and America's fading memory of the Great War, in: The Journal of Military History 72/2, 2008, pp. 371-411.

- Trout, Steven: On the battlefield of memory. The First World War and American remembrance, 1919-1941, Tuscaloosa 2010: University of Alabama Press.

- United States Committee on Foreign Affairs: American battle monuments commission. Hearings before the Committee on foreign affairs, House of representatives, Sixty-seventh Congress, second and third sessions, on H.R. 9634 and H.R. 10801, for the creation of an American battle monuments commission to erect suitable memorials commemorating the services of the American soldier in Europe. March 15-20, November 28, December 7-9, 1922, Washington, D.C. 1922: Government Printing Office.

- United States Committee on Military Affairs: To authorize mothers and unmarried widows of deceased World War veterans buried in Europe to visit the graves. Hearing before a subcommittee of the Committee on Military Affairs, United States Senate, Seventieth Congress, first session, on H.R. 5494, a bill to enable the mothers and unmarried widows of the deceased soldiers, sailors, and marines of the American Forces interred in the cemeteries of Europe to make a pilgrimage to these cemeteries. May 14, 1928, Washington, D.C. 1928: Government Printing Office.

- Winter, Jay: Sites of memory, sites of mourning. The Great War in European cultural history, Cambridge 2000: Cambridge University Press.