Introduction↑

Key aspects of the African American experience in the First World War include the circumstances surrounding the mobilization of African American soldiers; various responses of black leadership figures to the quickly spreading global conflict; various degrees of racial discrimination; the overall military experience of African American soldiers in the U.S. and France; and the impact of the First World War on the modern Civil Rights Movement.

Like most Americans, very few African Americans understood the implications of the European conflict on the course of everyday life in America, especially during a time when race relations in the United States were quickly eroding. With the election of President Woodrow Wilson (1856-1924), a Democrat, for a second term in 1916, previous gains made by blacks came under attack. Race leaders like William Monroe Trotter (1872-1934), who had been strong advocates for Wilson’s first term, urged blacks, who had traditionally voted Republican, to support the reelection of the nation’s twenty-eighth president based on his promises of “fair and equal treatment for all.”[1] Unfortunately, those promises were never realized. Under the Wilson Administration, some agencies within the federal government introduced a policy of racial segregation, a decision that reduced the number of jobs available to African Americans in the nation’s capital, including in the Post Office Departments, the Bureau of Engraving, and the Navy.[2] This discrimination increased the already odious environment of racial prejudice that empowered white Americans to abuse African Americans at will, further denying the promises of democracy to a segment of the population that lacked the protections guaranteed by the Constitution of the United States.

President Woodrow Wilson also endorsed David Llewelyn Wark Griffith’s (1875-1948) racist film The Birth of a Nation (1915), which promoted a mythical representation of black humanity as biologically inferior and morally depraved and supported the vigilante style of the Ku Klux Klan as a measure to regulate black progress. Responding to the growing popularity of the film, the preeminent historian and representative of African Americans, William Edward Burghart Du Bois (1868-1963), painted a bleak portrait of the future for race relations in America: “I personally reprobate the exhibition as having on the whole a very unfortunate influence, and possibly the effects may be far more reaching than we can at present anticipate.”[3] Du Bois was correct in his assessment; incidents of racial violence and the lynching of blacks would increase both during and after World War I (WWI). Close to 380,000 African American men would be inducted into the United States army, with 200,000 serving in Europe and a little more than 40,000 seeing combat at the frontlines.

The Response of African Americans to the War↑

The beginning of the war in Europe halted most European immigration to the United States. A labor depression in the South and a growing need for labor in the factories in the northern industrial cities further encouraged American factory owners to actively recruit black labor from the South. White agents boarded southern-bound trains to Florida, Alabama, Georgia and Tennessee to offer jobs to the willing masses, most of whom needed very little convincing to accept the opportunity to leave the South, where the brutal act of lynching was a feature of the culture and the landscape.

By the winter of 1916, the Great Migration had been underway for nearly two years, with hundreds and then thousands of blacks moving to cities such as New York, Pittsburg, Detroit and Chicago, swelling their respective populations. In armament factories and meat packing plants, and as domestic labor in the homes of whites, African Americans commanded higher wages in the northern states than they would have received in the South. The opportunity to have running water, access to education and medical care helped establish migration patterns that blacks would maintain throughout the first half of the 20th century. In turn, industries welcomed the new source of labor, which kept productivity high. Unfortunately, the employment of newly arrived blacks as competition to white American and immigrant workers and as strikebreakers in the urban steel and manufacturing industries led to several violent confrontations. Episodes such as the East St. Louis riots of 1917, which left more than 100 African Americans dead and hundreds severely injured, was the result of an escalation of prevalent racial attitudes and labor tensions. These factors, among others, represented a series of unintended consequences, many of which would impact the future of blacks in America for generations.

Prior to WWI, nearly 90 percent of all African Americans lived in the Southern United States in the shadow of slavery, with most working the same lands that their forbearers had toiled in as human chattel. These newly arrived transplants to the northern industrial centers helped establish a foundation for the future social, economic and political infrastructures needed for the development of a powerful black middle-class. As such, they became capable of challenging the stifling system of oppression and Jim Crow segregation responsible for impeding the advancement of the community.

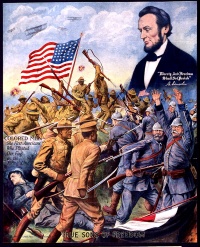

Shortly after the United States declared war on Germany, the Selective Service Act was enacted on 18 May 1917. The act required men between the ages of twenty-one and thirty-one, including African American men, to register with the United States government at their local recruitment stations. African American intellectuals and race advocates saw military service as the ultimate sacrifice and proof of one’s citizenship and loyalty. They differed on whether African Americans should demand immediate equal rights as a condition for their wartime military service.

Some civil rights leaders established a firm philosophical position against serving a country that systematically denied African Americans their citizenship and basic human rights. For African American leaders like William Monroe Trotter, A. Philip Randolph (1889-1979) and the Jamaican-born Marcus Garvey (1887-1940), the war was a contest among the imperial powers of Germany, France and England to expand their stranglehold on resources abundant in Africa, India and South America.

Du Bois agreed, to a point. As early as 1915, Du Bois wrote most lucidly about the impact of the war on the darker peoples of the world and how their futures were bound to be shaped by the outcome of the war.[4] In The Crisis, the official publication of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), Du Bois used his editorial pen to demand on behalf of the American Negro the right to serve as soldiers and officers on the battlefields of Europe. He believed that during America’s time of need, African Americans needed to demonstrate their “unfaltering loyalty” to realize the “larger finer objects of this world battle.”[5] In a very famous editorial that he would later regret writing, Du Bois urged African Americans to put their “special grievances” aside and “close ranks” with white Americans for the duration of the crisis.

Like Du Bois, the Jewish American chairman of the NAACP, Joel Spingarn (1875-1939), who had been a strong advocate for African American rights and privileges, recognized the importance of military service as public confirmation of citizenship and manhood. In support of black advancement in the war, the Baltimore Afro-American argued for the participation of black men in the war effort, recognizing the global conflict as the “greatest opportunity for the colored man since the Civil War.”[6] Furthermore, Spingarn believed that African American soldiers needed black officers with unimpeachable character and moral standards who could train men not only for combat in France, but for the challenges ahead in a dramatically changing American society as well. However, in order to do this, civil rights leaders had to put aside their demand for an end to segregation and accept separate training facilities. Sending black officers to train in “Jim Crow” camps provoked tremendous controversy within the black community.

In August 1917, Chandler Owen (1889-1967) and A. Philip Randolph founded The Messenger, a magazine dedicated to challenging the hypocrisy of American democratic ideals. In their publication, Owens and Randolph argued that “Patriotism has no appeal to us; justice has. Party has no weight with us; principle has,” especially in the United States, where black people had been traditionally denied equality and basic human rights.[7] The African American journalist Kelly Miller's (1863-1939) open letter to Woodrow Wilson further articulated the fundamental contradictions in having African American men fight for democracy in Europe, when at home they were subject to “cruelty and outrage on the part of [their] white fellow citizen who assumes lordship over [them].”[8] The controversy would continue as black men, who were required under law to register like their white counterparts, made up the bulk of draftees in some southern towns.

Local draft boards denied African American men the draft exemptions typically given to fathers and men who were the single source of income for their families. Unhealthy black men not fit for service were sent to training camps, while healthy, unattached white males stayed home as a result of the local draft boards fraudulently identifying black residents as the most qualified for service.[9] Yet this unfortunate discrimination opened a floodgate of opportunities that could not have been anticipated. The fact that African American men were able to claim their manhood publicly through military service challenged and changed how they viewed themselves as men and as citizens, as well as how they viewed the possibilities for future opportunities. Although hard to conceive of at the time, the United States was on the verge of long overdue changes to the body politic.

Military Experience↑

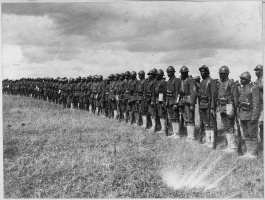

Before the first training camp opened, African American men experienced resistance from military officials, commissioned white officers and white soldiers, all of whom regarded their presence as unsatisfactory and a threat to entrenched American race relations. Racist beliefs that black soldiers could not be depended on to serve with dignity and honor due to their so-called inherent weaknesses in character, mental capacity and moral turpitude shaped the experiences of all drafted and enlisted men. Adopting a policy of strict segregation to maintain and preserve discipline, the War Department organized separate units in direct response to the problems anticipated between white soldiers, who would not accept black soldiers as equals, and black soldiers, who would refuse to be intimidated by whites and their sense of entitlement. The conditions of the facilities for black troops were tragic, and, in most cases, resembled southern chain gang camps.

In the South especially, black troops were denied adequate medical treatment, clothing and housing. In some instances, shelter for African American troops “often consisted of tents without the flooring or boxing usually provided for whites housed under canvas, and sometimes without stoves in winter weather.”[10] Overpopulated barracks, the lack of proper sanitation facilities and infrequent medical attention quickly advanced the spread of preventable diseases. The health, morale and overall welfare of black troops mattered less to military officials, since most black soldiers were destined to serve in the rear as the muscle needed to supply America’s white soldiers on the field of battle with the necessary supplies, rather than as fighting troops.[11]

As early as June 1917, black labor battalions, or stevedores, were responsible for loading the hulls of cargo ships with supplies bound for France. Black stevedores had also arrived in the port cities of Brest, St. Nazaire and Bordeaux, where they unloaded ships laden with supplies for the front. These noncombatant soldiers were also responsible for road building, constructing ammunition dumps, cooking, building warehouses and salvaging materials from the theater of war. The assumed low status of black soldiers also made them vulnerable to ill-treatment by their white counterparts, many of whom asserted their sense of superiority in the belief that no black man had any rights that a white man was bound to respect. Even in France, white men accustomed to exercising their assumed dominance over blacks did so with impunity. Sadly, in some instances, white soldiers and officers participated in murdering black soldiers as a form of sport.[12]

Black Officer’s Training Camp and the Western Front↑

While black soldiers relegated to the Services of Supply (SOS) served as the muscle needed to transform America’s potential military force into a state of readiness on the ground, a great experiment was underway at Fort Des Moines, Iowa, the site of the Colored Officers Training Camp (COTC). These men were to lead units in the all-black 92nd, one of two lone divisions reserved for black combatants. Accommodating 1,250 candidates between the ages of twenty-five and forty, the camp was supported by General Leonard Wood (1860-1927) and Secretary of War Newton D. Baker (1871-1937).[13] Of the African American men selected, a great majority came from black colleges and universities, such as Howard University, Hampton Agricultural and Industrial Institute, Lincoln University, Atlanta University, Morehouse College, Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute and Morgan College. Under the direction of General Charles Ballou (1862-1928), the COTC candidates were trained to endure the physical and mental rigors of war. Ballou insisted that “strong bodies, keen intelligence, absolute obedience to order, unflagging industry, exemplary conduct, and character of the highest order” were required for success.[14] Yet, even with their college training, commitment to the war effort and the endorsement of officials in Washington, whites resisted the implications of the “so-called Negro” being capable of leadership, courage and bravery under fire. Most were fearful of the possibility of a repeat of the 1917 Houston, Texas incident involving Regular Army black troops, which resulted in the deaths of sixteen white civilians and thirteen black soldiers, who were hanged for murder.

Originally planned as a three month endeavor running from July to September, the COTC at Fort Des Moines was extended for more than a month, causing nearly half the men to quit with the belief that the “War Department never intended to commission colored men as officers in the army.”[15] The disappointed candidates returned home without fanfare. However, the 639 candidates who remained prepared for the long haul. A month later, on 14 October 1917, the COTC graduated 106 captains, 329 first lieutenants and 204 second lieutenants, all ready for assignment. Praising the accomplishments of the newly commissioned officers, special assistant to Secretary of War Baker, Emmett J. Scott (1873-1957) of the Tuskegee Institute, spoke directly to the men at the official ceremony, arguing that “wherever you go, and wherever you serve, I know you will bear in mind that in a very real sense, you and those who serve with you, have in your keeping the good name of a proud, expectant and confident people.”[16]

After receiving their assignments, the 639 officers dispersed to take their places in one of seven camps where the various units of the 92nd Division were located. Unfortunately, the 92nd Division included a number of white southern officers who maintained their beliefs in the inferiority of African Americans and vehemently rejected the authority of the newly commissioned officers. As a result of the failing of United States Military to reign in and replace the racist commanding officers, the deployment of the 92nd to the Western Front is remembered as one of the saddest chapters related to black soldiers in the war effort.

By mid-September 1918, the 368th Regiment of the 92nd Division, along with the 77th American Division and the French 4th Army, moved into position near the Argonne Forest in preparation for an offensive against the German army. Prior to this assault, the all-black regiment had had very little training in maneuvers under heavy shelling, lacked the proper equipment to cut through the thick entanglements, and were not supplied with the necessary “signal flares and grenade launchers.”[17] These factors made them ill-prepared to maintain their organizational effectiveness in combat. What’s more, the trust black soldiers had in their white commanding officers was continuing to erode as “many of the field officers seemed far more concerned with reminding their Negro subordinates that they were Negroes” than preparing them to execute the orders handed down from General Headquarters.[18] On 28 September, the 368th came under intense German fire, and in the confusion of combat several companies “withdrew in disorder,” choosing to retreat to the trenches in an effort to regroup.[19] Not only was the regiment accused of cowardice, but the accusation was extended to the entire 92nd Division.

Conversely, the most recognized and well-known black infantry regiment to serve during the First World War was the 369th of the 93rd Division. Historically known as the Harlem Hellfighters, the 369th was originally formed out of the 15th New York National Guard Regiment created by William Hayward (1877-1944) in 1916. The regiment included men from all walks of life, including laborers, doctors, lawyers, hustlers, baseball players, educators and musicians. Hotel bellhops like Needham Roberts (1901-1949) and red cap porters like Henry Johnson (1897-1929) signed up to better their financial situations and serve the interests of their communities, while simultaneously taking advantage of the opportunity to be recognized as men. In an effort to develop a topnotch regimental band to help with recruitment and maintenance of morale, Colonel Hayward recruited black composer and musician James Reese Europe (1881-1919) and music arranger Noble Sissle (1889-1975). Europe’s reputation as a bandleader and his ability to draw a crowd presented Hayward with an opportunity to convince African Americans in and around Harlem to join the 15th in defense of their right to fight for democracy and the possibilities connected to their serving for a greater good.

As early as 15 July 1917, the 15th New York National Guard had 2,000 men, including forty-seven officers, three of whom were African American. On 12 March 1918, the all-black regiment was assigned to the French army as replacement troops – one of four infantry regiments from the 93rd Division who served with the French for the duration of the war. It is here that the 369th made a name for itself. Serving at the front for 191 consecutive days, the Harlem Hellfighters defended not only the French lines against the German assault, but the honor and pride of all African Americans whose futures would be impacted by the outcome of the war as well. Indeed, the heroism of Private Henry Johnson, whose valiant efforts to save fellow soldier Needham Roberts from being captured by a German raiding party earned him the French Croix de Guerre, supported the notion that African American soldiers were not only brave, but were honorable and loyal too. Another notable example of exemplary service was Corporal Freddie Stowers (1896-1918) of Company C of the 371st, who died in the line of duty leading his men into battle against overwhelming odds. Unfortunately, Stowers would not be recognized for his bravery until 1991, when President George H. W. Bush posthumously awarded the WWI hero the Medal of Honor, America’s highest honor for military service.

The war in Europe also marked a time of great possibility for African American men to experience aspects of true democracy. In many of the port cities of France and in Paris, African American soldiers were usually accorded the same respect that white soldiers were granted. There were also exceptions; James Reese Europe and his regimental band, for instance, were elevated as celebrities, due in part to their introduction of jazz music to the country through public concerts. In the eyes of the French, African American soldiers were part of the Allied forces that came to liberate their country from the German assault. As a result, numerous African American men enjoyed an unprecedented freedom to move without restrictions in public spaces, eat in some of the best restaurants and patronize businesses without provocation. The sense of dignity and pride inspired by these experiences would be a turning point in the transformation of African American men upon their return to America. Simultaneously, the war in Europe exposed African Americans to blacks from different parts of the world, including Africa, the West Indies and Canada, all of whom had their own ideas and experiences related to blackness and the significance of the war in Europe on their futures. The war had brought together peoples of African descent in a way that had previously been unparalleled. This new Pan-African understanding of the world served as a clarion call for black leadership to cultivate black political power throughout the African diaspora and begin to strategize ways to work towards a universal sense of freedom and democracy.

Conclusion: Impact on Civil Rights Movement↑

Although the war came to a close in Europe with the signing of the Armistice on 11 November 1918, African Americans questioned whether or not the aims of the global struggle for democracy and freedom would promote full citizenship for blacks in America. In The Crisis, regarding the role of the returning African American soldiers, Dubois argued succinctly that “by God in heaven, we are cowards and jackasses if now that the war is over, we do not marshal every ounce of our brain and brawn to fight a sterner, longer, more unbending battle against the forces of hell in our own land.”[20] Southern whites had a clear answer to the question of Negro suffrage. In the Southern Workman, Joshua Blanton relays a New Orleans white man’s public response to the enthusiasm African Americans had after raising money for the war effort through the purchase of bonds and stamps: “You niggers are wondering how you are going to be treated after the war. Well, I'll tell you, you are going to be treated exactly like you were before the war, this is a white man's country and we expect to rule it.”[21] When the troops returned home from France, the hostilities shown to a great majority of them by numerous whites in the South and in the North affirmed the resistance to the changed views that African American soldiers had. By the summer of 1919, the violence being unleashed against recently discharged soldiers still in uniform was a clear indicator of the question of full-citizenship rights and privileges for blacks; a resounding no was echoed throughout the country.

In cities like Washington, D.C., Omaha, Nebraska and Chicago, Illinois, riots broke out when African Americans challenged their previous status as holdovers from slavery. Unwilling to back down from threats of violence, African American men who were trained to fight and defend themselves on the battlefield fought back against attempts to return them to their previous condition as defenseless human chattel. These same men, along with African American women, would become active participants in the liberation process, helping to transform their traditionally marginalized community into an organized and militarized movement for social, economic and political freedom and equality. Organizations such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) actively recruited former soldiers into their ranks, many of whom became prominent leaders. Men like Charles Hamilton Houston (1895-1950), who, like other African American officers, had served in France and experienced the hatred of his fellow American soldiers first hand, decided to use his energy and time to fight for those who “could not strike back” by becoming a lawyer.[22] After graduating from Harvard Law School, Houston became a central figure in the movement against Jim Crow laws that enforced racial segregation in all public facilities, primarily in the Southern and border states. As dean of the Howard University Law School, he would influence the career of his most prestigious student, Thurgood Marshall (1908-1993), who would become a United States Supreme Court Justice and whose impact on the whole notion of separate but equal resulted in the 1954 Brown vs. Board of Education United States Supreme Court decision, which outlawed segregated public schools. Indeed, the fight for racial equality, social justice and the true meaning of democracy would be fought for throughout the twentieth century by a generation born out of the initial global struggle for freedom in the First World War.

Pellom McDaniels III, Emory University

Section Editor: Edward G. Lengel

Notes

- ↑ Lunardini, Christine A.: Standing Firm. William Monroe Trotter's Meetings With Woodrow Wilson, 1913-1914, in: The Journal of Negro History 64/3 (1979), p. 245.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 246.

- ↑ Opinions: The Slanderous Film, in: The Crisis, 11/2 (1915), pp. 76-77.

- ↑ Opinions: The War, in: The Crisis, 10/3 (1915), p. 125.

- ↑ Editorial, in: The Crisis, 14/2 (1917), p. 60.

- ↑ “War Secretary Approves Negro Officers Camp, in: The Afro American (19 May 1917), p. 1.

- ↑ The Messenger, 1/1 (1917).

- ↑ The Disgrace of Democracy, in: The Afro American (25 August 1917), p. 4.

- ↑ See Barbeau, Arthur E./Henri, Florette: The Unknown Soldiers: Black American Troops in World War I, Philadelphia 1974, pp. 34-38 and Williams, Chad: Torchbearers of Democracy. African American Soldiers in the World War I Era, Chapel Hill 2010, pp. 52-58.

- ↑ Barbeau and Henri, The Unknown Soldiers 1974, p. 51.

- ↑ Williams, Torchbearers of Democracy 2010, p. 111.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 113.

- ↑ Scott, Emmett J.: The American Negro in the War, Washington, D.C. 1919.

- ↑ Barbeau and Henri, The Unknown Soldiers 1974, p. 59.

- ↑ Scott, The American Negro in the War 1919, p. 90.

- ↑ Address of Emmett J. Scott, Special Assistant to the Secretary of War, in: Chicago Defender (20 October 1917), p. 12.

- ↑ Barbeau and Henri, The Unknown Soldiers 1974, p. 150.

- ↑ Slotkin, Richard: Lost Battalions. The Great War and the Crisis of American Nationality, New York 2005.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 288.

- ↑ Levering Lewis, David: W.E.B. DuBois 1868-1919. Biography of a Race, New York 1993, p. 578.

- ↑ Blanton, Joshua E: Men in the Making, in: Southern Workman 48 (January 1919), p. 20.

- ↑ See Houston, Charles Hamilton: A Gallery, sponsored by Cornell Law School. www.law.cornell.edu/houston/houbio.htm.

Selected Bibliography

- Anonymous: The disgrace of democracy, in: The Afro American, 25 August 1917, pp. 4.

- Anonymous: The messenger, in: The messenger 1/1, 1917.

- Anonymous: War secretary approves negro officers camp, in: The Afro American, 19 May 1917, pp. 1.

- Anonymous: Address of Emmett J. Scott, Special assistant to the secretary of war, 20 October 1917, p. 12.

- Barbeau, Arthur E. / Henri, Florette: The unknown soldiers. Black American troops in World War I, Philadelphia 1974: Temple University Press.

- Blanton, Joshua E.: Men in the making, in: The Southern Workman 48, 1919, pp. 17-24.

- Du Bois, W. E. B (ed.): Opinions. The slanderous film, in: Crisis, 1915, pp. 76-77.

- Du Bois, W. E. B. (ed.): Editorial, in: Crisis 14/2, 1917, pp. 60.

- Du Bois, W. E. B (ed.): Opinions. The war, in: Crisis 10/3, 1915, pp. 125.

- Grossman, James R.: Land of hope. Chicago, Black southerners, and the Great Migration, Chicago 1989: University of Chicago Press.

- Lentz-Smith, Adriane Danette: Freedom struggles. African Americans and World War I, Cambridge 2009: Harvard University Press.

- Lewis, David L.: W. E. B. Du Bois, New York 1993: Henry Holt & Co.

- Lunardini, Christine A.: Standing firm. William Monroe Trotter's meetings with Woodrow Wilson, 1913-1914, in: The Journal of Negro History 64/3, 1979, pp. 244-264.

- Mjagkij, Nina: Loyalty in the time of trial. The African American experience during World War I, Lanham 2011: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc..

- Nalty, Bernard C.: Strength for the fight. A history of Black Americans in the military, New York; London 1986: Free Press; Collier Macmillan.

- Scott, Emmett J.: Scott's official history of the American Negro in the World War, Washington, D.C. 1919: War Dept..

- Slotkin, Richard: Lost battalions. The Great War and the crisis of American nationality, New York 2005: H. Holt.

- Wilkerson, Isabel: The warmth of other suns. The epic story of America's great migration, New York 2010: Vintage Books.

- Williams, Chad Louis: Torchbearers of democracy. African American soldiers in the World War I era, Chapel Hill 2010: University of North Carolina Press.