Introduction↑

New Zealand’s women were enmeshed in the Great War. Whether or not they supported it or had family members fighting, the conflict changed daily life, infusing everything from shop displays to the women’s pages of every magazine. What women wore became laden with meaning and social events were re-oriented around fundraising. Changes to work and family were most immediate for New Zealand’s women. The group of women for whom worked changed most dramatically were medical professionals – nurses, doctors, masseuses and occupational therapists – who served both overseas and in New Zealand.

Propaganda and Rhetoric↑

New Zealand women were subject to the same propaganda images as women in Britain and the other dominions, with very little official propaganda being produced in New Zealand. The figures of Britannia, the Belgian refugee and her children, and appeals to men to enlist “for your wives’ and children’s sake” were all familiar to New Zealand women.[1] As with women in other combatant nations, appeals to women – from those both supporting and opposing war – were made on the basis of their maternal role. The family metaphor was employed liberally in every sector of women’s mobilization, from fundraising for “our boys” to nursing and rehabilitating the wounded. The Red Cross image and slogan of “the greatest mother in the world” (first drawn for the American Red Cross) incorporated the overwhelmingly young and single Volunteer Aid Detachment worker into the “natural” role of motherhood. Not only was this an acceptable motivation for women entering war, but it helped to de-sexualise the situation of young men and women in the intimate relationship of nursing.

Newspapers regularly ran stories of “women’s part” in the war, especially emphasising the role of women in Britain in munitions work and other non-traditional occupations. Women’s columns provided advice on “what to send to Egypt” as well as reporting on the new fashion for kepis in London in the winter of 1914-15.[2] Advertisers too, used military language and flags in their appeals to female customers, as well as emphasising the Britishness of their companies. Where their British parent companies supplied the military, their patriotism was trumpeted in their advertising. Emphasising the need for wartime thrift, shops encouraged women to “join the Army of satisfied customers...when every penny should be spent to the best advantage.”[3]

Political and Patriotic Organisations↑

New Zealand’s women had been enfranchised in 1893 and had a significant history of political participation through a wide range of organisations, ranging from the Women’s Christian Temperance Union to the National Council of Women, some of which turned to supporting the war effort. The Victoria League for example, formed in New Zealand in 1905, was an organisation in which elite pakeha (European) and Maori women were very active during the conflict. Most notably, members Lady Annette Liverpool (1875-1948) and Miria Woodbine Pomare (1877-1971) established the “Lady Liverpool & Mrs Pomare’s Maori Soldiers’ Fund” to support the men of the Maori contingent. There were twenty-eight committees of Maori women around the country “providing entertainment and care parcels, some containing food that Maori soldiers would appreciate, such as mutton birds.”[4]

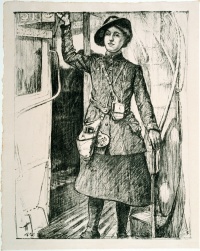

During the war, several new organisations emerged such as the Women’s Anti-German League and the Women’s National Reserve branch. Modelled on similar British organisations, the Women’s Anti-German League was established in January 1916 and focused its campaigns on people of German descent living in New Zealand. They protested against the employment of enemy aliens, pressured the government to amend naturalisation laws, and, harnessing women’s economic power in the household, urged consumers to only buy British goods.[5] The Women’s National Reserve was launched in August 1915, to demonstrate that, in addition to the reserve of manpower recorded in the National reserve war census, New Zealand also had a reserve of women-power. The Women’s Reserve invited women to register their names for employment in professional and clerical fields, farming, shops, factories and domestic employment. For women who had never worked, but were happy to be trained as letter carriers or tram conductors, there was a category of "general" employment.[6] While the prime minister was quick to claim that the National Reserve had not been intended to include women, political cartoonists used the appearance of the group to further pressure men who had not already volunteered for military service.

Women’s peace and anti-militarist groups also pre-dated the war. Several were founded in New Zealand in response to the South African War (1899-1902), and had campaigned against the introduction of compulsory military training for boys and young men introduced in 1909. The philosophies underpinning women’s objections to militarism included religious beliefs, socialism, and a widespread opinion that the maternal role made women natural advocates for peace. More generally, they argued that women and children’s welfare was always at risk during war. When the Great War was declared, they were re-energised. The Canterbury Women’s Institute, National Peace Council and the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom shared a small but dedicated membership.[7] They petitioned the government, held conferences and meetings (which were often rowdily broken up by returned soldiers), and offered practical help to men wanting to evade conscription after its introduction in August 1916. Sarah Saunders Page (1863-1950) wrote constantly to Prime Minister William Massey (1856-1925) protesting the introduction of repressive wartime regulations that suspended civil rights and denied citizens their "right of free thought, free speech and public discussion on the questions of utmost importance to the community."[8]

Working in the Battle Zones and Britain↑

Unlike other nursing services, the New Zealand Army Nursing Service (NZANS) struggled to be accepted by the New Zealand government. Six nurses had accompanied the New Zealand force that occupied the German colony of Samoa in 1914, but the NZANS was not formally established until early 1915. Although more than 400 nurses had offered their services in the first month of the war, the first contingent of NZANS did not leave New Zealand until April 1915 on the SS Rotorua.[9] They were distributed throughout hospitals in Alexandria and Cairo upon their arrival in Egypt. New Zealand’s first hospital ship Maheno followed soon after, bound for the Dardanelles. New Zealand nurses served in a variety of war theatres including France, Salonika, and Egypt and in hospitals in Britain and France. Hospital ships, casualty clearing stations and field hospitals were all venues for New Zealand nursing sisters. Conditions were often difficult and the work took its toll.

The most significant loss of life of New Zealand nurses was when the British transport ship Marquette was torpedoed on 23 October 1915. Thirty-six New Zealand nurses were among the 700 passengers and crew. Ten of the nurses drowned, and the others endured up to twenty hours in the water waiting for rescue. Their stories, and the praise for their actions under fire reported by officers on board, fellow survivors and rescuers, were widely reported in the New Zealand press.[10] In total, approximately 650 nurses served with the NZANS.

Rather than waiting for the offers of NZANS to be accepted, however, many New Zealand nurses left for Britain, paying their own passage, while other New Zealand women enlisted in Australia with the Australian Army Nursing Service.[11] New Zealand nurses also served with the Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service and the British and French Red Cross.

The first generation of female doctors also turned their hands to war work. At home, several women doctors took on the patients of their male colleagues, thus freeing them for enlistment. Others travelled overseas. Dr. Agnes Bennett (1872-1960), having had her offer of service rejected by the New Zealand army, travelled to Britain with her sister who was a trained nurse. Agnes Bennett served in hospitals in Cairo and then with the Scottish Women’s Hospitals in Serbia, while her sister nursed with the British.[12] Ettie Rout (1877-1936), a founding editor of the socialist newspaper Maoriland Worker, established the New Zealand Volunteer Sisterhood and raised enough money to send a group of women to Egypt in October 1915, and followed in December 1915. Although not medically trained, Rout saw the pressing need for venereal disease prevention and became a staunch advocate for venereal disease education among troops. She corresponded with doctors, educated herself on the latest treatments for and preventatives against venereal disease, and put together prophylactic kits including ointments and condoms. Frustrated by the army’s refusal to educate or equip soldiers, Ettie wrote a series of articles for the New Zealand press (only one of which was ever published) in an attempt to embarrass the government into acting. The army finally did adopt venereal disease education, and Ettie’s packs, but there was a tacit understanding that the New Zealand population must never be informed of this.[13]

In addition to medical work, women’s work in Britain, Egypt and Europe took a variety of forms. Thousands of civilian women worked for the British Red Cross in Britain, many of whom were visiting Britain or travelling in Europe when war broke out. Finding themselves effectively stranded for a time, many volunteered and some decided to remain and take up war work of some kind. Poet Ursula Bethell (1874-1945) was travelling in Switzerland when war broke out, and she spent the war in London teaching and volunteering as a waitress in the evenings at the New Zealand Soldiers’ Club.[14] Noeline Baker (1878-1958), who had been in London since 1905, worked in Surrey where she established a training farm for women and coordinated women agricultural workers.[15] Others, including the wives of officers travelled to Britain specifically to help. After Elizabeth Stewart’s (1880-1967) husband died of disease contracted on Gallipoli, Elizabeth remained in Egypt and then Britain working in the New Zealand hospitals. Musicians toured France giving concerts for troops, and women worked as ward orderlies, cooks and laundresses in hospitals. The numbers of New Zealand women working in Britain and Europe are impossible to quantify but a variety of sources, including memoirs, the newspaper for Australians and New Zealanders in London the British Australasian and defence department correspondence, reveals hundreds of women anxious to "do their bit" for the empire and "our boys".

Working in New Zealand↑

For those who could not afford to go to Britain, or did not have the inclination, there was plenty to be done in New Zealand. Despite the outflow of men, women’s participation in the paid workforce did not change dramatically during the war according to the census. Indeed, it was in the decade before the war that significant expansion of employment opportunities for women occurred. The number of women recorded as engaged in paid employment in the 1911 census was double that recorded in 1891.[16] In addition, the percentage of working women engaged in the "domestic" sector had declined from 46 percent to 38 percent in the same period.[17] During the war years employment in the domestic sector continued to decline, while the "professional" sector grew to employ nearly one-in-five working women by 1921.[18]

The census is at best a partial picture, however, and when supplemented by memoirs, oral histories and newspapers, it is clear that work did change character for many women during the war. Women’s established role in textile production and in the preserving sheds of fruit and meat processing factories became redirected to war production by early 1915. By mid-1915 for example, all ten of New Zealand’s woollen mills were producing exclusively for the military: indeed, by the end of the war newspapers were reporting a nationwide shortage of woollen goods on the civilian market.[19] The inroads female teachers had made into primary school education in the pre-war years were extended slightly into secondary teaching (much to the horror of parents and governors of boys’ schools) as masters joined up. Women’s role in agriculture, always under-represented in the census, expanded as womenfolk and children took on more work, often unpaid. Jessie Wallace worked on her brother-in-law’s orchard during the war. She recalled,

Not all women could recall their wartime work with such sanguinity. Katarina Te Tau (1899-1998), an academically gifted fifteen-year-old when war broke out, was forced to leave school. She recalled with some bitterness that the war resulted in her

Heavy industry remained fiercely protected by unions however, and without a munitions industry, there were no openings for women in skilled industrial occupations in New Zealand. The arbitration court ruled in 1916 that women performing work in skilled trades such as butchering and baking must receive equal pay and conditions to men, cementing the lockout of women from the point of view of both employers and unions.[22] Instead, women filled the burgeoning vacancies in clerical work in banks, small businesses and, finally, the public service. The New Zealand public service had been a male-dominated workforce with fewer than sixty female employees in a service of almost 5,000 in 1908. By 1916, the Public Service Commissioner was forced to relax regulations excluding women, and by war’s end the majority of the 3,000 new temporary positions had been filled by women.[23]

Despite the rhetoric of a unified society working tirelessly for their soldier-boys, the war took its toll. For working-class women, rapidly rising inflation made life increasingly difficult by 1916. In the traditional industry of textile production, female workers were pushed to their limits by insatiable military demand for blankets and fabric. In March 1916, women at the Wellington Woollen Mills began a strike after negotiations failed to secure an end-of-year bonus from the profitable company. The workers claimed they were "working 60 hours a week for soldiers" but were no longer earning a "living wage". The strike, because of the unusual number of women involved, tapped into many social anxieties, including the spectre of prostitution. One newspaper asked whether women’s earnings were "conducive to keeping them in good health and keeping them straight." The women’s patriotism was also called into question but their defenders maintained the strikers "were the same girls who at the time of the [fundraising] carnival had given the whole of their time and money...and now they are called unpatriotic!" The women ultimately won a 10 percent wage rise, but their union was simultaneously fined £50 for participation in an illegal strike.[24]

Patriotic organisations received thousands of applications for financial assistance from soldiers’ relatives, especially as the cost of living rose substantially by 1917. "Lady visitors" for one committee reported even respectable families in financial difficulties, praising mothers for nonetheless keeping houses and children clean despite privation. Women took in boarders, washing and ironing, others’ children, as well as relying on contributions from older daughters and sons in order to make ends meet.[25] Women’s political organisations used such evidence of privation caused by the absence of male breadwinners to agitate for a "mothers’ pension" along the lines of the American model, or some form of child support. Their persistence into the post-war period resulted in the Family Allowance legislation being introduced in 1926. The war had not transformed women’s work in New Zealand, but had made clear the pitfalls of a social model based on male "breadwinners".[26]

Volunteer Work↑

Mobilizing men for military service required the mobilization of civilians to equip and support them. The voluntary effort in New Zealand was enormous and almost all-encompassing. Women’s patriotic organisations sprang up immediately on the outbreak of war, several of them using the Red Cross title, although the foundations of the Red Cross in New Zealand “are not clear-cut.”[27] Despite the organisational complexity, the Red Cross emerged as the largest voluntary organisation of the war, with hundreds of branches across the country, and others of the more than 500 patriotic organisations contributing to their fundraising efforts.[28]

Sewing was the first order of the day, while the prevalence of factory-made knitted items meant that a generation of women and children had to be taught to knit. Then the knitting of socks and pyjama draw-cords (elastic was not commonly used in clothing until the 1940s) became a constant occupation. A wartime poem described the ubiquitous clicking of needles, describing socks “knitted in the tramcar/knitted in the street/knitted by the fireside/ knitted in the heat...knitted by the seaside/ knitted in the train….”[29] Literally millions of items were cut, rolled, hemmed, knitted, sewed, labelled, packed and posted overseas through the voluntary efforts of women. But this massive effort was not without its tensions: young working women could feel resentful that after a full day’s work on their feet at the factory, more leisured middle-class women expected them to come to evening meetings and sew into the night. Cartoons and letters to the editors of newspapers also revealed a certain amount of domestic resentment as women prioritised sewing for strangers perhaps to the detriment of the patching and repairs of their own family’s clothing.

Women were also integral to the fundraising efforts of the Red Cross and other patriotic organisations. Fancy dress balls, pageants, queen carnivals and endless bazaars and concerts were driven by the energies of thousands of women across the country. In 1920, the Red Cross put the combined value of funds raised and goods provided during the conflict at £1,348,876; the equivalent of one pound seven shillings for every man, woman and child at a time when women textile workers earned between two shillings and one pound seven shillings per week.[30]

Conclusion↑

Women’s commitment did not end at the signing of the peace treaty. Indeed, New Zealand was plunged into a new crisis even as the Armistice was declared when the influenza epidemic took hold, killing 8,600 people in a little over two months.[31] Red Cross, St. John’s Ambulance Society and VAD workers and organisations were all crucial to supporting families and communities during the flu, but in the process exposed thousands of caregivers to the virus. Echoing recruitment appeals, St. John’s urged its female members to "remember people are dying from lack of attention. You may be able to save a life. It is worth all the effort and sacrifice you can make. Act promptly."[32] The enormous death toll added to the trauma of a terrible conflict for New Zealanders.

Beyond the crisis of the flu, the burden of healthcare for wounded and traumatised veterans fell heavily on families, especially women. The New Zealand government wound up its repatriation department, including military hospitals, in 1922, clearly demarcating continuing medical care as a family responsibility.[33] Women’s lives changed course as they faced years and sometimes decades of caring for brothers and husbands who suffered from a wide range of disabilities, illness, alcoholism and what came to be called soldier "burn out" or "debility". Long-term unemployment was also a significant effect of the war on men, resulting in precarious lives characterised by moving the family to follow the work, or long periods of separation.

Citizenship had been achieved decades before the outbreak of war, and women’s paid work changed in only minor ways during the conflict. Women’s war efforts were largely mobilized around families, and the effects of the war continued to be felt most strongly in this realm.

Kate Hunter, Victoria University of Wellington

Reviewed by external referees on behalf of the General Editors

Notes

- ↑ For all of these examples, see Gibson, Stephanie: First World War Posters at Te Papa, in: Tuhinga 23 (2012), pp. 69-84, issued by Museum of New Zealand, Te Papa Tongarewa, online: http://collections.tepapa.govt.nz/publication/3737 (retrieved: 28 October 2015).

- ↑ See for example: What to Send to Egypt, in: Star (Christchurch), 1 March 1916, p. 7; London Fashions, in: Star (Christchurch), 3 February 1915, p. 7.

- ↑ W Harris & Sons advertisement, in: Otago Daily Times (Dunedin), 10 February 1916, p. 2.

- ↑ Pickles, Katie: A Link in ‘The Great Chain of Empire Friendship’. The Victoria League in New Zealand, in: Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 33/1 (2005), p. 35.

- ↑ Francis, Andrew: ‘To be truly British we must be anti-German’. New Zealand, Enemy Aliens and the Great War Experience, 1914-1919, Oxford 2012, p. 84.

- ↑ Women’s Branch of the National Reserve, in: Ashburton Guardian, 19 August 1915, p. 6.

- ↑ Woods, Megan: Re/Producing the Nation. Women Making Identity in New Zealand 1906-1925, MA thesis, University of Canterbury 1997, p. 80.

- ↑ Sarah Saunders Page cited in Hutching, Megan: ‘Turn Back This Tide of Barbarism’. New Zealand Women Who Were Opposed to War, 1896-1919, MA thesis, University of Auckland 1990, p. 122.

- ↑ Rogers, Anna: While You’re Away. New Zealand Nurses at War 1988-1948, Auckland 2003, pp. 47f.

- ↑ Rogers, While You’re Away 2003, pp. 94-113.

- ↑ Harris, Kirsty: More than Bombs and Bandages. Australian Army Nurses at Work in World War I, Newport (NSW) 2011; Maclean, Hester: New Zealand Army Nurses, in: Drew, T.B. (ed.): War Effort of New Zealand, Auckland 1923.

- ↑ Hughes, Beryl: Bennett, Agnes Elizabeth Lloyd. Biography, in: Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Te Ara. The Encyclopedia of New Zealand, online: www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/biographies (retrieved: 30 August 2015).

- ↑ Tolerton, Jane: Rout, Ettie Annie. Biography, in: Dictionary of New Zealand Biography, online: www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/biographies (retrieved: 1 September 2015). See also Tolerton, Jane: Ettie. A Life of Ettie Rout, Auckland 1992.

- ↑ Mary, Alison/Laura, Valerie: Ursula Bethell, in: Macdonald, Charlotte/Penfold, Merimeri/Williams, Bridget (eds.): The Book of New Zealand Women. Ko Kui Ma Te Kaupapa, Wellington 1991, pp. 83-86.

- ↑ Baker, Leah: Noeline Baker, in: Macdonald/Penfold/Williams, Book of New Zealand Women 1991, pp. 37ff.

- ↑ Luxford, Sarah: Passengers for the War? The Involvement of New Zealand Women in Employment during the Great War, 1914-18, MA thesis, Massey University 2005, p. 9.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 9.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 17.

- ↑ Hunter, Kate/Ross, Kirstie: Holding on to Home. New Zealand Objects and Stories of the First World War, Wellington 2014, p. 82.

- ↑ Jessie Wallace in Edmonds, Lauris (ed): Women in Wartime. New Zealand Women Tell Their Story, Wellington 1986, p. 105.

- ↑ Katarina Wharerauaruhe Te Tau. Interview with Judith Fyfe, 27 January 1983. Oral Archive 220, Wairarapa Archives, Masterton, New Zealand.

- ↑ Olssen, Erik: Building the New World. Work, Politics and Society in Caversham 1880s-1920s, Auckland 1995, p. 81; Robertson, Stephen: Women Workers and the New Zealand Arbitration Court, 1894-1920, in: Labour History 61 (1991), pp. 34f.

- ↑ Nolan, Melanie: Keeping New Zealand’s Home Fires Burning, in: Crawford, John/McGibbon, Ian (eds.): New Zealand’s Great War. New Zealand, the Allies and the First World War, Auckland 2007, p. 496.

- ↑ Hunter/Ross, Holding on to Home 2014, pp. 82f.

- ↑ Nolan, Keeping the Home Fires 2007, pp. 508ff.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 513.

- ↑ Tennant, Margaret: Across the Street, Across the World. A History of the Red Cross in New Zealand, 1915-2015, Wellington 2015, p. 30.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 36f. See also Woods, Re/Producing 2005, p. 82.

- ↑ Printed note to accompany socks in Patriotic Fund parcels, in Hunter / Ross, Holding on to Home 2014, p. 94.

- ↑ Tennant, Across the Street 2015, p. 41; For women’s wages in the textile industry see Hunter/Ross, Holding on to Home 2014, p. 82.

- ↑ Rice, Geoffrey/Bryder, Linda: Black November. The 1918 Influenza Pandemic in New Zealand, Christchurch (1988) 2005.

- ↑ Hunter/Ross, Holding on to Home 2014, p. 246.

- ↑ Walker, Elizabeth: ‘The Living Death’. The Repatriation Experiences of New Zealand’s Disabled Great War Servicemen, MA thesis, Victoria University of Wellington 2013.

Selected Bibliography

- Edmonds, Lauris (ed.): Women in wartime. New Zealand women tell their story, Wellington 1986: Government Printing Office.

- Hunter, Kate / Ross, Kirstie: Holding on to home. New Zealand stories and objects of the First World War, Wellington 2014: Te Papa Press.

- Hutching, Megan: 'Turn back this tide of barbarism'. New Zealand women who were opposed to war, 1896-1919, thesis, Auckland 1990: University of Auckland.

- Luxford, Sarah: Passengers for the war? The involvement of New Zealand women in employment during the Great War, 1914-1918, thesis, Palmerston North 2005: Massey University.

- Nolan, Melanie: 'Keeping New Zealand home fires burning'. Gender, welfare and the First World War, in: Crawford, John / McGibbon, Ian C. (eds.): New Zealand's Great War. New Zealand, the Allies, and the First World War, Auckland 2007: Exisle Publishing, pp. 493-515.

- Patrick, Rachel: An unbroken connection? New Zealand families, duty, and the First World War, thesis, Wellington 2014: Victoria University of Wellington.

- Rogers, Anna: While you're away. New Zealand nurses at war 1899-1948, Auckland 2003: Auckland University Press.

- Tennant, Margaret: Across the street, across the world. A history of the Red Cross in New Zealand, 1915-2015, Wellington 2015: New Zealand Red Cross Society.