Introduction↑

France was the main stage upon which the operations of the Western front played out and was also where the outcome of the war was decided in 1918, after having been consumed by it since 1914.[1] This trench war was punctuated with great battles of attrition that involved a combined effort by the world’s largest industrial powers. In terms of both men - from five continents - and materiel, it was surely in France that the unleashing of modern industrial war reached its paroxysm.

Over the past twenty years, research into France during the period from 1914-1918 has become a vibrant and global field of study. While there are still many aspects to address, writing a synthesis today involves delving into a rich and abundant bibliography.

A Great Power Slowly Emerging from Isolation↑

France in 1914 was a great power. The defeated country of 1870 seemed like a distant memory. Proclaimed on 4 September 1870, the Third Republic had managed to sever its ties with the Second Empire, deemed responsible for the defeat to Prussia and its allies, but it had also managed to preserve some traditions that encouraged the country’s gradual recovery. The republic was therefore able to cash in on the thrust of urban and economic modernization, colonial conquests and benefit from the global influence of Paris.

France was present on all continents; it had over 55.5 million inhabitants outside of mainland France and stretched over 10.5 million square kilometres. The “colonial party” had been heavily criticized in the 1880s, but was broadly accepted by the turn of the century. Even prior to 1914, the question of using a far larger number of colonial troops than ever before should a conflict arise had been openly addressed, notably by Colonel Charles Mangin (1866-1925) in his book La force noire (1910).

Colonization had made it in part possible to forget the humiliating defeat suffered at the hands of the German Second Reich, the new strongman of Europe. While the colonial adventure was somewhat risky - as the 1898 Franco-British Fashoda incident in Sudan and the two Franco-German crises in Morocco in 1905 and 1911 had shown - , these issues had nonetheless been overcome.

The aggressive “global policy” of Wilhelm II, German Emperor (1859-1940) which broke with Otto von Bismarck’s (1815-1898) cautious Realpolitik, helped France put an end to the isolation in which it had found itself from 1870 to 1890. French diplomacy seized the opportunity to sign the Franco-Russian alliance in 1892, followed by the “Entente Cordiale” with the British in 1904. This group formed the Triple Entente (1907) to counter the Triple Alliance (1891) of Germany, Austria-Hungary and Italy.

Although, in hindsight, this two-sided system of alliances has often been presented as a factor that encouraged escalation, it was no means the only cause. It can just as easily be seen as a force to neutralize the European powers. And yet following the second Moroccan crisis in 1911, distrust between the chancelleries and amongst public opinion in each country was again a growing issue.

An Army of Citizen-Soldiers↑

Driven less by the need for revenge than it was by a desire for national defence, France’s military recovery began long before 1911. A series of laws adopted between 1872 and 1905 created a mandatory, universal two-year military service;[2] following heated debate, this was extended to three years in 1913. Alongside this, the army modernized. The French army was capable of very rapidly mobilizing 1.7 million men. For boys, the army gradually became a second republican school. By celebrating itself during holidays and military parades, like during Bastille Day celebrations on 14 July, the army found its niche in the newly formed national conscience of citizens.[3] For republicans, the army was no longer simply the spearhead of the nation at arms; it presented itself as an army of citizen-soldiers prepared to defend the homeland, nothing like the army defeated in Sedan.

A Republic within a Prosperous Country↑

The patiently constructed republican identity of the early 20th century was both the cement of the country and one of its main strengths. In the end, only intransigent Catholics, very locally-rooted notables and right-wing leagues - and among the latter, particularly the Action Française created in 1899 - continued to be uncompromisingly anti-republican.

This consensus based on shared values certainly did not mean there were no tensions or struggles, as the string of successive governments starting in 1910 and the success of new opposition political parties notably illustrated. The Socialist Party - the French Section of the Workers’ International (SFIO) - with its charismatic leaders, like Jean Jaurès (1859-1914), and the Confédération générale du travail (CGT) union, which both aimed to concurrently represent the interests of the working class, saw their audience-base increase. While one part of the SFIO and particularly the CGT embraced anti-state and revolutionary rhetoric, socialism in France was for the most part a profoundly republican movement and school of thought.

Beyond the political and social tensions and affairs, the regime was broadly accepted both in the countryside and in factories. France’s renewed prosperity, which ramped up markedly after 1900, also contributed to the country’s internal stability. The pre-war years were among the best the country had experienced. The Franc was stable, strong and convertible into gold. France presented the contrasted image of being both a rural society - over 55 percent of inhabitants lived in municipalities of less than 2,000 inhabitants and over 40 percent worked in the primary sector - but also resolutely modern in the urban and industrial spheres. France was the fourth largest industrial power in the world at the time. This balance helped ensure both the economic and social stability of the country.

The prosperity of its economy drove improvements in French standards of living which were second only in the world to Great Britain. A corollary as much as a part of this phenomenon (quite like the effects of education and literacy), birth rates and fecundity began to decrease more rapidly after 1900. Family planning and the number of children people had were less and less hinged on fatality, “the laws of nature” and religious orders. The family model of one, two or at most three children was increasingly common and had practically become the norm by the eve of the war.

This model slowly became a topic of concern as France differed more and more from its neighbours in this respect at a time when the influence of a country was measured in terms of its demographic thrust. While in absolute terms, with 39.6 million inhabitants in the 1911 census, France was still as populated as Great Britain and more so than Italy, it was smaller than Germany - and the latter had an entirely different family model based on large families.

This demographic parameter aside, France was the image of a country that was rich, powerful, politically stable and whose culture was undeniably influential. And yet this “great nation” entered the war without really managing (or maybe even wanting) to inflect on the course of events.

Entering the War↑

Some recent research has begun to reassess the role played by France in the crisis of July 1914.[4] France indeed played a role in the start of the conflict, notably via the promise made to Russia by President Raymond Poincaré (1860-1934) about France’s unwavering support. This, however, occurred quite late in the game. The origins of the crisis that led to the war were in the Balkans, where French interests were secondary and indirect, despite the fact that France had always been a traditional ally to Serbia. When Austria-Hungary gave Serbia the ultimatum on 23 July, the same day that Poincaré left Russia to return from an official trip, the dual monarchy’s idea was to use the situation to teach Serbia a lesson via a short and localized conflict, and to allow Germany, which promised its full-fledged support, to test out Russia’s political will.[5] The ultimatum expired on 25 July at 6pm; when the Austrians chose this moment, they were aware that Poincaré would not yet be back in France. They as such hoped to delay any consultation between France and Russia. Three days later, on the morning of 28 July, the dual monarchy declared war on Serbia. France, like all European countries, was then faced with the question of how to react should the conflict escalate.

Like most European leaders, Raymond Poincaré has occasionally been accused of wanting the war or at least of not having done much to prevent it from breaking out. Yet the situation was such that France by no means played a leading role in the crisis of July 1914. The trip to Russia by the President, President of the Council René Viviani (1863-1925) and Minister of Foreign Affairs cut them off from the rest of the government and, de facto, stifled their ability to act at least until their return to Dunkirk on 29 July. On top of this, there were major differences of opinion between Poincaré and Viviani. The latter was much more hesitant about the attitude to adopt vis-à-vis Russian initiatives, whereas Poincaré wanted to reassure his Russian counterparts to preserve the Franco-Russian alliance. Poincaré was further persuaded that Germany was fundamentally insincere and that it wanted to go to war in any case and at all cost, which did not push him towards moderation.

Once it became clear that Russia was going to ignore the calls for caution and mobilize unilaterally, Poincaré accepted, apparently without much emotion, the prospect of war. In the end, the responsibility of France, its President and government hinged more on their relative absence from the international scene in July 1914 and then on their acceptance of a war deemed inevitable, than on their supposed war mongering, as claimed by the left and pacifists after 1918.

Resolve↑

To grasp the state of mind of the population in early August 1914, we need to take into account both short- and medium-term factors. Through various crises and challenges, the Third Republic had managed to create a sense of citizenship and united republican patriotism. Although this patriotism was for the most part defensive, there were nonetheless occasional surges which sometimes morphed into nationalism. However, as the debate in 1913 over increasing military service from two to three years and the legislative elections of April-May 1914 (in which the Socialist party gained ground while the right wing lost seats) had shown, France in 1914 was not a revengeful or overly aggressive country.

Media coverage in the middle of the summer of 1914 was not very conducive to fairly assessing the gravity of the situation, either. The assassination in Sarajevo that had been front page news in late June gradually disappeared from media reports. The trial of Madame Henriette Caillaux (1874-1943) who had shot dead Gaston Calmette (1858-1914), editor in chief of Le Figaro, to clear the name of her husband, leader of the Radical Party, had begun on 22 July. News of the Austrian ultimatum to Serbia the next day, followed by Austria-Hungary’s declaration of war on 28 July, the day before the verdict, as such came in the midst of a busy news period.

The death of Jean Jaurès, who was assassinated on the evening of 31 July by Raoul Villain (1885-1936), was seen as both an internal political event and a product of the current international crisis. In the days leading up to his death, Jaurès had called on workers, unions and socialist parties to do everything possible to stop the spread of the crisis, while also making multiple statements in support of the policy approach taken by the French government. The situation became even more complicated for socialists following news of the Russian mobilization on the morning of 31 July. They could see that this would risk definitively dragging France into war since Germany would likely respond to Russian mobilization by also mobilizing. Jaurès and his friends were as such torn between their utmost hostility towards Tsarist Russia, their desire for peace and their support for the government. On 28 July, the CGT union announced that it would not lead a general strike movement against the war and on the evening of 31 July, following the crushing news about the death of the socialist leader, it solemnly reiterated the unanimous position taken by members of its confederal committee.

On 1 August, Germany declared war on Russia, France’s ally, and France mobilized. That morning, the French as such had to come to terms with the death of Jaurès, the country’s mobilization and grasp the scope of the inevitable turn taken in the conflict. It is therefore understandable that the prevailing emotion after the declaration of war was that of astonishment.

A series of mixed emotions followed on the heels this astonishment: enthusiasm for some, resignation or resolution[6] for the majority. There were certainly many loud displays of patriotism, notably around train stations, at intersections and on the terraces of cafés in large cities. These resulted in the vandalizing of several shops deemed (correctly or incorrectly) to be owned by “enemies”, like for example shops belonging to the Swiss brand Maggi which were ransacked and looted. The reality of the collective sentiment, however, was much closer to what historian Marc Bloch (1886-1944) has described as follows: “The men for the most part were not hearty; they were resolute, and that was better.”[7] France’s mobilization was conducted in an orderly fashion and nearly 3.5 million men donned a military uniform within a few days. The country indeed tipped into the war extremely quickly.

War at the Front↑

In 1914, the war began in France with a series of catastrophic battles. The first month of the conflict had effects that lasted right up to the end of 1918 since the German advance resulted in the country being split in three: war-front France, occupied France and behind-the-lines France. Plan XVII, which was meant to advance very quickly and break through the front along France’s eastern borders in Alsace and Lorraine, ended in defeat despite the taking of Mulhouse, which was quickly lost again. Only a small portion of Alsace, around the town of Thann, remained in French hands throughout the war. With the exception of the defensive battle of Grand Couronné, which staved off the capturing of Nancy, the other battles almost all ended in defeat. Overall, August and September 1914 were among the deadliest months of the war. Following the Battle of the Marne, after only six weeks of combat, the French had already lost about 100,000 men. On 22 August 1914 alone, 27,000 French soldiers were killed, making it the deadliest day in French military history. While the average number of French losses during the First World War was roughly 900 soldiers per day, this increased to about 2,400 deaths per day over this six-week period.

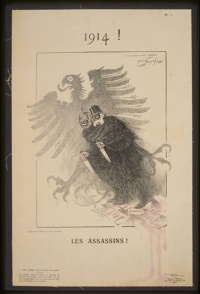

These first weeks were also brutal for civilians. The German atrocities committed by worn-out troops (wrongly) convinced that they were the target of irregular soldiers resulted in over 900 deaths in the civilian population and dozens of burned out villages, notably in the Meurthe-et-Moselle department.[8] This worked to terrorize the population and increase the flow of refugees, but it also helped cement the French population’s support for its soldiers. “German barbarism” and references to the atrocities of 1914 were indeed the most popular topics found in propaganda (in the broadest sense) right up to 1918.

A combination of fatigue within the German troops, the largely utopian nature of the Schlieffen Plan and the combined errors of Helmuth von Moltke (1848-1916) in the general staff and Alexander von Kluck (1846-1934) at the head of the right wing of the German army allowed Joseph Joffre (1852-1931) to regain control and halt the German advance on the Marne (5-12 September 1914).

The battle was followed by a “race to the sea” during which the two warring parties both attempted a vast movement to side-step the other by moving towards the North West. Riddled with fierce battles, notably at Ypres, this race was lost by both sides and the front stabilized from the North Sea to the Swiss border. At the same time, the armies had dug into the ground to such an extent that the front was transformed into a double network of trenches separated by a no man’s land. In this configuration, each side was both a besieger and besieged. Until the spring of 1918 and despite numerous attempts to break through, the defensive position won out over the offensive position, thus resulting in a war that lasted far longer than the most pessimistic prognoses. Between 1914 and 1918, 7.9 million French citizens were called to serve in the armed forces. In addition to these, 600,000 more soldiers from the colonies (who were not French citizens) enlisted in the army and about 500,000 saw combat in Europe.

Over 4.2 million soldiers were wounded, over 500,000 were taken prisoner and roughly 1.4 million were killed.

For soldiers, the war was defined by two types of experiences: very difficult daily life and moments of actual combat which were a form of paroxysm within this everyday life. Soldiers’ lives were above all defined by a day to day existence that was particularly trying, comprised of very long walks, hard labour and difficult conditions, mostly outside and in all seasons. But life was also comprised of long periods of inactivity, discouragement and boredom that were in part filled with reading, writing letters, doing craftwork in the trenches or trying to deal with lice, rats and other vermin. War transformed the bodies of men, too. The term “poilu” (which literally means “hairy”) was the nickname very quickly given to French soldiers during the First World War. It spoke of the consequences that life in the trenches had on their bodies and faces. Facial hair was a symbol of their virility, but also of the physical transformation caused by the war.

While this very difficult daily life occasionally resulted in a sort of “trivialization of war,”[9] soldiers remained under the constant threat of death, which meant that things were very different from times of peace: “For the soldier fighting in the ranks, the war was just a long tête-à-tête with death” wrote writer and soldier Pierre Chaine (1882-1963).

In addition to this gruelling and painful daily life, there was a whole other set of experiences that were often more perilous still: combat. These experiences were extremely diverse: fighting in the open countryside in 1914, the coups de mains of trench warfare, the intense and sustained bombing of artillery preparations, the repeated and sustained attacks of the large battles of attrition during which soldiers’ daily lives were sometimes completely upended, like being snatched up and replaced by an apocalypse that lasted for days or even weeks at a time.

The deadliest year for France was 1915, with about 350,000 deaths, although proportionately 1914 was even deadlier with 300,000 men killed in only five months. The French army sought to break through the front in the Vosges, at Hartmannswillerkopf, at Artois and in Champagne in the spring and in the autumn. The use of artillery preparation and drum fire meant to destroy the enemy’s defences never actually succeeded in breaking through, which explains why French losses were even greater than in 1916, which was when the large total battles of Verdun and the Somme occurred.

Indeed, the scale of fighting changed in Verdun. The most intense phase of the battle lasted from 21 February 1916 to July, but it endured until December. Erich von Falkenhayn (1861-1922) wanted to get the Western front moving again and chose to attack the French in this hilly sector. Roughly 1 million shells of all sizes were fired on the first day alone. The battle remained undecided until June, but the Germans never actually managed to break through the front. Philippe Pétain (1856-1951), followed by his successor Robert Nivelle (1856-1924) organized a continuous fleet of trucks that used the “sacred way”, according to the expression coined by Maurice Barrès (1862-1923), to get men and materiel to the front–roughly 90,000 men and 50,000 tonnes of materiel per week. 6,000-8,000 vehicles drove on the route each day. Already in 1916, the battle of Verdun became a symbol of the Great War. Once the battle had begun and the French resistance been proven, Falkenhayn nonetheless insisted on pursuing the attacks over and over again. Given the failure to advance, he claimed after the fact that the goal had not been to break through or get the front moving but rather to wear down the enemy and “bleed him dry”. And yet this strategy chosen after the fact and by default also failed. Although Falkenhayn had bled the French army, he had done the same to his own troops. The losses were indeed comparable, with 160,000 missing or killed on the French side and over 140,000 on the German side. There were in addition to this 200,000 wounded on both sides.

While the Battle of Verdun was raging, the British and French launched an offensive on the Somme starting on 1 July. This offensive had been planned for a long time, since 6 December 1915. The initial goal of the Anglo-French offensive had been to get things moving again and force the enemy to retreat as quickly as possible by “pushing” him back–the British named this battle the Big Push. The 1 July 1916 offensive at the meeting point of the French and British armies was a catastrophe. In a single day, nearly 20,000 soldiers from British Empire armies were killed and slightly less than 40,000 were wounded. This represented half of the British troops engaged on 1 July. The attacks in the Somme sector which, unlike Verdun, stretched over several dozen kilometres, nonetheless continued until the end of autumn without the set goals ever being met. The final result was even worse than in Verdun since in less than six months there were likely close to 1.2 million casualties in all.

While for the French the Battle of Verdun earned its status as the symbolic battle of the Great War, the Somme was actually even more deserving of the title. It was a global battle in a world war whereas Verdun was an essentially Franco-German affair. Moreover, it was exemplary in showcasing how totalization had taken hold of the Western model of war. The radicalization of the war’s violence resulted in a change in the nature of combat which was becoming impossible in the traditional sense of the term. It also required that the French army gradually adapt between 1914 and 1918 - a painful but ultimately efficient change; this was done both by taking into account “feedback” from the front and via modernization that was both tactical and technical, in connection with the industrial and scientific sectors.[10]

Given the violence experienced but also inflicted, French historians - likely more so than in other countries - have focused a lot on the factors underpinning French soldiers’ ability to hold on. This has in turn led to at times very heated debate over soldiers’ “consent”[11] to the war as one of the factors that might (or might not) explain their endurance. Other factors were of course also at play, such as the ties of solidarity between soldiers within a “primary group”, the internalization of social roles that notably explain why young men at the time found it normal to don a uniform. Expectations and hopes about the pending victory were perhaps also influential.

One of the main factors was the largely defensive perception of the war. Right from August 1914, Germany was perceived as the aggressor. The fact that the war played out right in the middle of the country further reinforced this feeling which in any case persisted throughout the war. Not only did people need to defend themselves and the homeland, they also needed to ensure victory in order to liberate the population in the ten departments that had been invaded.

The Occupied Territories: A Second Front↑

Focused as they were on the essentially political and military facets of the war, historians for a long time overlooked the case of those in occupied France, as well as the refugees who fled the invasion, but these topics are now being increasingly studied.

Although the occupation initially resulted in a decrease in violence against civilians, which had culminated during the period of invasion from August-September 1914, the situation was seen as doubly scandalous: firstly, due to the spectacular measures taken by the occupier (e.g. hostage taking, deportations, executions and forced labour), but also due to the occupier’s invasion into people’s everyday lives (e.g. the switch to German time, restricted movement, requisitions, boarding at people's homes, price hikes and poorer living conditions).

The economic exploitation of the occupied territories resulted in supply difficulties which worsened during the war since this exploitation intensified as the effects of the blockade were felt in Germany. Those occupied indeed quickly became dependent on humanitarian aid, notably from the Commission for Relief in Belgium (CRB). In addition to requisitions, freedom of information and movement were also closely controlled. Not only was it impossible for refugees to return or communicate with the non-occupied departments, but movement within the invaded territories was also difficult and subject to approval. Information was carefully managed and was released by a controlled press that published the views of the occupier, like the Gazette des Ardennes.

Other specific measures under the occupation were even more brutal: 1,500 residents of Amiens were deported to Germany between 1914 and 1918. This was a response to alleged acts of violence by the population during the invasion, but it was above all meant to maintain order. Even when people were evacuated towards France, via Switzerland, and allowed an escape from the unenviable state of occupation, their evacuation was obviously very traumatic. It was even more poorly viewed when people were evacuated towards Germany, particularly when such evacuations appeared to be totally incomprehensible and arbitrary, like the evacuation of 15,000 women at Easter 1916 or when they occurred alongside systematic destruction that was meant to slow the enemy’s advance, like during the voluntary retreats of 1917 and the forced retreats of 1918.

Quickly, it was no longer simply goods that were requisitioned, but also manpower. Requisitioned worked were sent to work in Germany, on-site or even near the front. This was nothing short of forced labour.

Given the situation, a certain resistance towards the occupier emerged. It sometimes took the form of small, individual acts of passive resistance, but there were also veritable resistance networks that published clandestine journals, hid allied soldiers or helped them escape into neutral countries, and acts of spying. When the Jacquet network, which ex-filtrated Allied soldiers, was dismantled in 1915, two hundred people were arrested. In all, 225 people were executed in Belgium and France for acts of resistance. Lille resident and Intelligence Service agent Louise de Bettignies (1880-1918), who headed a network of a hundred people, became an icon of the French resistance after her death from illness in a prison in Germany on 27 September 1918.

At the opposite end of the spectrum to such organized resistance, rapprochement occasionally occurred between those occupied and the occupier in some of the most rural areas which endured far less severe occupation regimes than urban areas did. This appears to have been the case in the Somme and the Vosges. Since the occupation was a fundamentally dissymmetrical affair that brought into contact men and civilian populations comprised primarily of women, there were sometimes affective and sexual relations between occupiers and the occupied. Although a broad palate of examples exists, the overall number was most likely quite small. Rape and prostitution aside, promiscuity also led to more or less ephemeral relationships. These were nonetheless viewed with a great deal of suspicion, as seen in the recurring and particularly heated debate over the illegitimate births of “enemy children.”[12] In any case, such phenomena were limited in scope. The trial and punishment of such cases was relatively uncommon and mostly involved people convicted of trafficking with the occupier.

Behind the Lines: The Home Front in the Total War↑

For a long time, historiography really insisted on the differences and tension between the front, occupied territories and life behind the lines. There was indeed very real tension that was expressed various ways. Incomprehension sometimes arose, for example, when soldiers discovered, during leave or periods of convalescence, that life behind the lines carried on, including leisure, artistic and cultural activities. The poilus–particularly those from rural areas–also had trouble understanding the strikes that took place in some factories. They often felt that workers were privileged and that their demands were not very legitimate. Figures such as “war profiteers” or “embusqués” (shirkers)[13] were omnipresent during the war and embodied the tension that existed between the front and those behind the lines who were often suspected of shirking their duties and the equality of all before such responsibilities. Alongside this and somewhat similarly, refugees and those repatriated from the regions invaded by the enemy were occasionally suspected - although this time by the civilian population that had to host them despite being under great duress - of taking advantage of their situation by receiving government benefit, of being spineless for having fled the enemy or, conversely, of having compromised themselves with the enemy and of being a sort of “Northern Boche” (‘Boche du Nord’)[14]. There were positive things, too, however: new forms of solidarity emerged and strong ties and connections united places, notably the war front and life behind the lines.

The massive mobilization at the start of the war tore apart families and couples, and also upset living conditions. The economic sphere was challenged by the state of war. There was a sudden lack of manpower and primary matter was hard to get hold of given the new geography imposed by the war. Unemployment, which was very high in some large cities, was rife during the first months of the war, thus occasionally reinforcing the material shortages felt by soldiers’ families.

While unemployment had dropped by late 1914 and early 1915 with the constantly growing demands of the war economy, another phenomenon of the early war period was much longer lasting behind the lines: mourning invaded the public sphere on the home front. Prior to the law of 27 July 1917 on wards of the nation (“pupilles de la nation”),[15] the charities that dealt with war orphans were quickly of cardinal importance. The first tie to bind the front and back was as such that of being a community of mourning and pain.

The fear of death, compounded by separation, also strengthened affective ties; these were notably expressed in the letters and parcels sent between the war- and home fronts. Millions of letters were posted daily. The civilian and military authorities were well aware of the importance of this epistolary connection and, while they certainly monitored it, they were careful to ensure that the army post office was in optimal form. There was as such a powerful affective tie maintained between the front and back that was never severed. It most likely contributed to the resilience of civilian actors when they were confronted with totalization. This connection also provided those behind the lines with information (that was much more reliable than what was published in the press) about the reality of life at the front and the hardship endured.

There were other ways, too, for those behind the lines to learn about the suffering endured at the front. War literature and narratives were published and became a popular genre. Soldiers on leave also provided information about life at the front or at least about comrades who were still behind the lines, even if it was sometimes difficult to communicate with close friends and family.[16] The rear was also quickly transformed into a giant hospital. The flow of wounded men was such that primary and secondary schools and barracks had to be turned into hospitals; beds were requisitioned in civilian hospitals and some convalescing soldiers were even sent to people’s homes. The presence of wounded and mutilated men on the home front made tangible the effects of the war’s violence.

These connections and flows were further strengthened through organized solidarity efforts. War charities flourished; for those behind the lines, they were a favoured means to participate in the conflict, along with war loans. Some were directly piloted by state bodies, like the very numerous solidarity days organized to raise funds for a whole series of causes: e.g., the poilus, prisoners, the wounded, orphans, refugees and those repatriated from the occupied departments.

Many charities were run by a combination of state, local authority and civil society actors. Churches, associations, unions and companies owned by prominent members of the bourgeoisie created all sorts of charities, sometimes together, but also occasionally in competition with each other. This one-upping of solidarity on the home front was based on a sense of ethics shaped by the example set by soldiers who “offered civilians a model for daily life that was dictated by duty, sacrifice and solidarity.”[17] Both explicit and implicit, this model sometimes made people feel guilty about not being on the front lines; it pushed them to showcase their involvement on the home front and embodied “the ambivalence of those behind the lines with regard to participation in the war effort.”[18] And yet the importance of the home front was compounded as the war dragged on and entered into a totalizing process; in the end, the war was not won on the front lines alone, but also with the massive investment of companies in the war effort and through the government’s ability to maintain its demands to the extent that could be tolerated, even if this balance was quite fragile at times, notably in 1917.

No one had anticipated that the war would last so long. And yet, against all plans, the war set in for the long term. Military and political leaders quickly realized the need to leverage the economy for the war effort. As early as 20 September 1914, the war minister Alexandre Millerand (1859-1943) had asked that French 75 production be ramped up tenfold, from 10,000 to 100,000 pieces per day. The nomination in May 1915 of socialist Albert Thomas (1878-1932) to the position of under-secretary of state for artillery, munitions and military equipment was an additional step towards streamlining the war economy and its piloting by the government, in collaboration with industry as well as the unions. The fact that the geography of the war had cut off France from part of its historical industrial regions in the North and East only compounded the emergency. The arsenals were not sufficient to address demand so enormous war factories were built from scratch, like the Citroën factory on Quai de Javel in Paris. A great deal of companies adapted their production for the war. In Lyon, the Gillet firm was the main supplier of war gas, notably of mustard gas; whereas in addition to trucks for the army, Berliet produced Renault tanks. In Clermont-Ferrand, Michelin supplied airplanes for the army.

At the start of the war, there were 50,000 workers in the armament sector in France. By the war’s end, there were 1.7 million people working in this sector, including over 420,000 women. The war economy was indeed a boon for employment. The unemployment problem at the war’s outset was resolved and labour shortages were actually quickly felt. Lengthening the work day was not sufficient to palliate the lack of manpower; it was necessary to quickly find other solutions. The Dalbiez law of 17 August 1915 allowed men to be appointed to the home front when it was deemed that they would be more useful behind the lines than at the front. Women also massively entered the industrial sector once reserved for men. Foreign and colonial workers–both at the front and behind the lines–were another pool from which labour was recruited. According to estimates, the Service de l’Organisation des Travailleurs Coloniaux (SOTC–Colonial Labour Organization Service) as such brought 200,000 “colonial workers” to mainland France, in addition to a non-negligible number of workers recruited via other channels.

The employment of people from these new categories was seen as temporary and connected to the war context; this limited, as we are well aware in the case of women, the medium term effects of such changes. Regardless, during the actual war years, a new social balance and new social figures, like the “munitionettes”, appeared.

1917: Danger on all Fronts↑

By 1917, several compounded factors (including the general sense of lassitude, failures at the Somme, the context of deepening political crisis, the effort required of those on the home front, mourning and sacrifice, worsened living conditions, inflation and shortages due to the war economy, as well as other more cyclical causes such as particularly cold winters) appeared to be wearing away at the country’s social fabric and for a time looked to be challenging the fragile balance that kept the war effort afloat. This resulted notably in increasingly visible protests starting in late 1916. The following year, 1917, was defined by a three-faceted military, political and social context of crisis.

On a military level, the failure at the Somme led to the sacking of Joffre at the head of the general headquarters in December 1916 and his replacement by Robert Nivelle (1856-1924), who represented a decidedly offensive turn. The latter again set out to break through the front in the Aisne department in the Chemin des Dames sector. The result was close to 40,000 deaths, 14,000 missing and 125,000 wounded without the set objectives being met. What soldiers had glimpsed as the end of the war suddenly veered off course with great brutality. Faced with an offensive that was incapable of bringing the anticipated end to the war, some soldiers revolted. It was actually those who were meant to advance to attack, despite the fact that failure was obvious, that refused to go. Those who were already facing off with the enemy continued to fight.

Some demands called for peace at all cost, but others were more mundane: e.g., improvements to soldiers’ living conditions or leave. The revolt worried the general staff greatly. Nivelle was replaced by Pétain and the mutineers were severely punished. The official figures generally given are 3,247 soldiers tried, 554 sentenced to death and forty-nine executed. In addition to such repression, new measures aimed at improving the daily lives of soldiers were gradually implemented to improve the replenishing of supplies and make the leave system run more smoothly.

The repression, restrictive military framework and granting of a few demands are not enough to explain everything, however. Most of the men mutinied for only a few days and, often, the denouement was negotiated by regimental officers who had remained in contact with the men.

The winter of 1916-1917 was extremely harsh and resulted on the home front in problems with the provision of heating supplies and food, and in price hikes that were much more severe than in previous months. Prices had been relatively stable in 1916, but increased by 25 percent on average in the first quarter of 1917. The distribution of ration cards and tickets also became widespread.

The combination of these factors led to strikes: first in the winter, then in the spring, after May Day and again in September. There was a large-scale labour movement in May-June that affected the entire country to varying degrees. Often, it was women - whose salaries were far lower than men’s - who launched the initial protests, went on strike and even occasionally demonstrated in the streets, often against the advice of the unions - like the Parisian “Midinette” seamstresses on 11 May, who were joined first by their female comrades and then by men from the armament sector. This movement never escalated into an all - out general strike, however, and there was no convergence with the mutinies occurring at the front at the same time. While pacifist slogans could be heard, the movement was appeased in part when its demands were granted for improved working conditions, shorter hours and wage increases, often obtained with the support of and via the unions.

Despite an ever-increasing number of unionized workers and the radicalization of part of this group and of the socialists, workers found themselves in an awkward position vis-à-vis the troops. They were viewed as walled up behind the lines and soldiers were often quite critical of mood swings from those behind the lines that risked delaying victory and thus the war's end.[19] Above all, a good number of workers also wanted to see a quick end to the war and felt that victory was still the best chance of reaching that goal. Those protesting rarely viewed their social protest and pacifism as necessarily leading to “defeatism” or “peace at all cost”, although such slogans were sporadically heard. Militant pacifism, like that of journalist Marcelle Capy who published Une voix de femme dans la mêlée in 1916 and anonymously got hired at a munitions plant in order to report on working conditions therein, was nonetheless not the norm.

The German offensive in the spring of 1918 also helped to remobilize the population, first in the face of danger, and then via a glimmer of hope that victory was finally within sight. The social problems, strikes and protests that had resumed in early 1918 and again in the spring gradually petered out, both because these movements were increasingly repressed but also because of what can be described as the “cultural remobilization of 1918.”[20]

Other, more structural causes also played a non-negligible role. Unlike countries such as Russia, Austria-Hungary and Germany, states like France and Great Britain managed, despite food shortages, to strike a balance between the needs of the front and those behind the lines, and between the countryside and cities. Both France and Great Britain were able to take advantage of colonial products, as well as imported goods from America, which were virtually impossible for the Central Powers to access due to the blockade. But this balance was also very tied to the way these different countries defined their citizenship and managed to preserve it despite the staggering blows that came with totalization. As Jay M. Winter has underscored, “while it may not seem logical at first glance, economic mobilization prior to a total war is less efficient under a regime dominated by the army than it is under a regime based on a civilian government.”[21]

For some social categories, the war period actually - and paradoxically - resulted in improved material conditions. For the urban middle class - the small minority of “war profiteers” aside - the war was a daily trial that often resulted in a stark decline in living conditions and notably in diet, and sometimes in impoverished conditions or even a drop in social standing.[22] But as Jay M. Winter has noted, rationing also had unwitting effects which occasionally resulted in a “transfer from the rich to the poor”: meat tickets sometimes allowed the poorest access to products they had not eaten before the war. Benefits for soldiers’ families and female labour also resulted in increased revenue for married, working women, particularly given that “the money now in their hands was no longer spent on alcohol”[23]. There was indeed a strong decrease in alcoholism behind the lines - although at the front wine continued to be widely distributed to soldiers -, both because of campaigns and anti-alcohol measures like the outlawing of absinthe in 1915, as well as due to price increases and the need for alcohol to create explosives. In a similar vein, in cities, the Great War also encouraged the dissemination of certain new ideas in the fields of hygiene and childcare, as well as fighting tuberculosis; these were notably promoted by the American Red Cross, which was very active in France. Such measures sometimes managed to limit increases in child mortality due to worsened living conditions or even, as was the case in Paris, actually lower such mortality during the war years.[24]

Such measures, however, had structural effects over the medium term that were not visible at the time; what was visible, were the increased prices, shortages, the poorer quality of basic goods such as bread, exhaustion at work and the cold in winter. But, “the war was won through sacrifice, not famine.”[25] In the end, like those at the front, people behind the lines managed to hold on. Moreover, through their endurance, they were of great help to the men battling the storms of steel of modern war. Georges Clemenceau (1841-1929) was able to tap into such sentiment when he came to power in November 1917 and enlisted the country to give its last effort and the final push necessary to support the poilus and their allies as they seized victory.

Towards Victory↑

For Clemenceau, who had been very critical of the policies of the preceding governments in his paper, L’homme libre, which became L’homme enchaîné, it was necessary to stop being a victim of total war (which he called “complete war” in his ministerial declaration on 20 November 1917), and instead embrace it and push it to its logical end.

In his analysis of the crisis, Clemenceau actually mainly targeted the political class. There had been four successive governments between December 1916 and November 1917. The crisis was so grave that Poincaré had to resort to asking his political foe to lead the government and appointed a smaller government entirely loyal to Clemenceau; the latter reserved for himself the Ministry of War in addition to the Council Presidency. The Chamber vested its broad confidence in him. He even invited the socialists to participate in his government but, having just left the Union sacrée, they refused the invitation - although three of them did join as “government commissioners”. Once invested, Clemenceau governed with an iron fist. He was hard on the other politicians, including the President of the Republic. He showed no mercy towards his political enemies, notably Louis Malvy (1875-1949) and Joseph Caillaux (1863-1944) that he had arrested and tried by the High Court of Justice. His style of governance, as well as the “Tiger’s” very strict programme earned him the quite exaggerated reputation for being a “dictator” amongst his adversaries. The main novelty was that since he was not bound by the Union sacrée, he did not have to seek compromise at all cost and could keep his majority in check by brandishing the socialist or pacifist menace. When parliamentarians resisted, he relied on his popularity which was rooted in the “cultural remobilization” that was itself one of the striking features of 1918, a year that had nonetheless begun in a trying manner for the government. Throughout the winter and especially in the spring of 1918, there had been more strikes that had spread across an ever larger part of the country; their tone was also more and more revolutionary and pacifist. And yet the movement waned when the German menace was felt at the start of the summer. In the face of imminent peril, the civilian population and soldiers reunited and remobilized together. There was a second phase to this remobilization after the balance tipped in favour of the Allies, when victory and peace finally appeared to be within reach.

The state propaganda machine was also overhauled in 1918, with the creation of the Commissariat général de la propagande (propaganda planning office). Civil society, too, was an important actor in trying to give meaning to the conflict; this was seen, for example, with the March 1917 founding of the Union des Grandes Associations Françaises Contre la Propagande Ennemie (Union of Large French Associations against Enemy Propaganda) which allowed its 30,000 member associations (representing their 12 million members) to coordinate their efforts. This group was particularly active in 1918: it organized 6,000 conferences across the country and published 100 million flyers and pamphlets. Such activity is illustrative of how involved the non-profit world was in what seemed more like a self-mobilizing endeavour than mobilization imposed from above. Giving meaning to the war was not the sole prerogative of those in control. Those subjected to it and those behind the lines also gave it meaning. The involvement of the non-profit sector was not unique, however: Bruno Cabanes[26] has analysed postal checks to show how the German offensive in the spring of 1918 and the Allied counter-attack spurred among soldiers a new wave of hatred towards the enemy. The statements made in letters reveal an extremely violent desire for revenge.

Remobilization was as such the result of both a rebound following the crisis of 1917 and early 1918 and a consequence of Clemenceau’s rise to power, but it was also a product of the war’s events and more specifically of the German offensive in the spring of 1918. In early 1918, Germany’s military position was still favourable. Ludendorff and Hindenburg had managed to transfer forty-three divisions from the Eastern front to the Western front. This transfer had begun even before the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was signed on 3 March 1918. Inside the ranks, however, the war had taken a greater toll in Germany than on the Allies. Among other things, the German numerical advantage on the front (199 German divisions versus 171) was likely to dwindle with the arrival of the Americans. Their advantage was also challenged by the immoderate and quasi-utopian ambitions to colonise the conquered territories in the East which forced the German army to leave numerous troops stationed in the area. The time frame was as such narrow for the German general staff which decided to launch a new type of offensive. Ludendorff launched a series of offensive attacks on 21 March: Operation Michael in Picardie in March; Operation Georgette in Flanders in April and late May; Operation Blücher in the Chemin des Dames sector and in Champagne. Each time, German troops jostled the allied troops and broke through the front. By early June, they had taken 50,000 prisoners and were only sixty-five kilometres from Paris. The capital was regularly bombed by giant German canons and Gothas bombers. France was once again stricken with fear and the exodus of 1914 was repeated. And yet the undeniable German tactical advantage was not strategically exploited since the troops were exhausted, had suffered extremely heavy losses without any relief and desperately lacked logistical support.

High on his tactical successes, Ludendorff was nonetheless set on pursuing his offensive attacks. He planned to attack in Champagne, and then along the Marne and in Flanders. From the outset, the offensive was conceived as being the final push and bore the telling name of Friedensturm. German troops attacked in Champagne on 15 July. This time, however, the Allies had anticipated the attack. They had considerably reinforced the rear and blocked the German advance within a few days. Ludendorff worsened the situation for his troops by refusing any tactical withdrawal until 2 August. By then, he was nonetheless forced to organize what remained of his troops to be on the defensive. He had lost a battle and could no longer win the war. 8 August was the “German army’s day of mourning”. That day, the Allied offensive in Picardie took the Germans by surprise; they lost 30,000 men, including 12,000 prisoners and 450 pieces of artillery. Given their impending defeat, the German army sunk into crisis. In October, some regiments had barely 300 men. While most soldiers fought every inch of the way despite very heavy losses, some, behind the lines, began a sort of “hidden strike” to postpone going to the front, or refused to go altogether. Rest and relief troops - which were indispensable - became unreliable or even impossible. The situation was compounded by the fact that Germany was losing its allies one by one, thus enabling the Entente powers to concentrate their troops on the Western front. With the help of a French expeditionary corps, the Italians repelled an Austrian attack; the French Far East Expeditionary Force forced Bulgaria to sign an armistice on 30 September 1918; and the front in Palestine was broken.

It was in this context that the Germans sent a first note to the American government with their conditions for an armistice on 4 October. Given the surprisingly stalwart and violent resistance of German troops, people on the Allied side did not generally believe that the war would be over before the spring of 1919. An Allied offensive in Lorraine was meant to begin in mid-November 1918. In the meantime, on 28 October, the German government resigned itself to accept an armistice whose terms were yet to be defined. It took the Allies over a week to negotiate these terms between them. The Allies agreed on the military clauses (the retreat of troops, a massive surrender of arms), whose goal was to strip the German army of any means to resume the struggle. Woodrow Wilson’s (1856-1924) “Fourteen Points”, however, which were the basis of the agreement’s political conditions and of the future peace, were far from unanimously accepted by the British and French.

The conditions were communicated to the German envoy, Matthias Erzberger (1875-1921), on 8 November in Rethondes, in the Forest of Compiègne. The following day the Kaiser abdicated before the German revolution. It was therefore up to the brand new German republic, which had just been proclaimed, twice, to accept and sign the armistice in the Forest of Compiègne. In Germany, France and all of the other countries, the end of the war was just beginning.

Nicolas Beaupré, Université Blaise Pascal - Clermont-Ferrand

Reviewed by external referees on behalf of the General Editors

Translator: Jocelyne Serveau

Notes

- ↑ This chapter is a very condensed version of our book: Beaupré, Nicolas: La France en guerre 1914-1918, Paris 2013.

- ↑ Crépin, Annie: Histoire de la conscription, Paris 2009.

- ↑ Vogel, Jakob: Nationen im Gleichschritt, Gottingen 1995.

- ↑ Schmidt, Stefan: Frankreichs Außenpolitik in der Julikrise 1914. Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte des Ausbruchs des Ersten Weltkriege, Munich 2009; Clark, Christopher M.: The Sleepwalkers: How Europe went to War in 1914, London 2013.

- ↑ Krumeich, Gerd: Juli 1914. Eine Bilanz, Paderborn 2013.

- ↑ Becker, Jean-Jacques: 1914. Comment les Français sont entrés dans la guerre, Paris 1977.

- ↑ Bloch, Marc: Memoirs of the War, 1914-1918, Cambridge 1988, p. 78.

- ↑ Horne, John/Kramer, Alan: German Atrocities 1914: A History of Denial, New Haven 2001.

- ↑ Loez, André: 14-18. Les refus de guerre. Une histoire des mutins, Paris 2010, p. 91, translated by JS.

- ↑ See notably Goya, Michel: La chair et l’acier. L’invention de la guerre moderne, Paris 2004; Rasmussen, Anne (ed.): Le sabre et l'éprouvette. L'invention d'une science de guerre. 1914-1939, special issue of 14-18 Aujourd’hui-Today-Heute, 6 (2003). See also Saint-Fuscien, Emmanuel: A vos ordres ? La relation d’autorité dans l’armée française de la Grande Guerre, Paris 2011 which provides a good illustration of how relationships of power changed in the army over the course of the war.

- ↑ Beaupré, Nicolas: Les Grandes Guerres 1914-1945, Paris 2013, pp. 1046-1050.

- ↑ Audoin-Rouzeau, Stéphane: L'enfant de l'ennemi 1914-1918, Paris 1995.

- ↑ Ridel, Charles: Les embusqués, Paris 2007.

- ↑ Nivet, Philippe: Les réfugiés français dans la Grande Guerre. Les “Boches du Nord”, Paris 2004.

- ↑ Faron, Olivier: Les enfants du deuil - Orphelins et pupilles de la nation de la Première Guerre mondiale (1914-1941), Paris 2001.

- ↑ Cronier, Emmanuelle: Permissionnaires dans la Grande Guerre, Paris 2013, pp. 239-255.

- ↑ Purseigle, Pierre: “1914-1918: les combats de l’arrière. Les mobilisations sociales en France et en Angleterre” in Beaupré, Nicolas/Duménil, Anne/Ingrao, Christian (eds.): 1914-1945: L’ère de la guerre. volume 1: Violence, mobilisations, deuil (1914-1918), Paris 2004, pp. 131-151, here p. 143, translated by JS.

- ↑ Ibid., translated by JS.

- ↑ Robert, Jean-Louis: Les Ouvriers, la Patrie et la Révolution: Paris 1914-1919, Besançon 1995; Horne, John: Labour at War. France and Britain, 1914-1918, Oxford 1991.

- ↑ See Beaupré, Nicolas: La France en guerre 1914-1918, Paris 2013, pp. 139-142.

- ↑ Winter, Jay M.: “Nourrir les populations” in Audoin-Rouzeau, Stéphane/Becker, Jean-Jacques (eds.): Encyclopédie de la Grande Guerre, Paris 2004, pp. 581-589, here p. 585, translated by JS.

- ↑ Lawrence, Jon: “Material Pressure on the middle classes” in Winter, Jay M./Robert, Jean-Louis (eds.): Capital Cities at War. Paris, London, Berlin 1914-1919, Cambridge 1997, pp. 229-254.

- ↑ Winter, Jay M.: “Nourrir les populations”, pp. 587-588, translated by JS.

- ↑ Rollet, Catherine: “The ‘other war’ I: protecting public health”, pp. 421-455; Winter, Jay M.: “Surviving the war: life expectation, illness and mortality rates in Paris, London and Berlin” pp. 487-524 in Winter, Jay M./Robert, Jean-Louis (eds.), Capital Cities at War, Vol. 1, pp. 502-505.

- ↑ Winter, Jay M.: “Nourrir les populations”, p. 588, translated by JS.

- ↑ Cabanes, Bruno: La victoire endeuillée. La sortie de guerre des soldats français (1918-1920), Paris 2004.

Selected Bibliography

- Alary, Éric: La Grande Guerre des civils 1914-1919, Paris 2013: Perrin.

- Audoin-Rouzeau, Stéphane / Becker, Annette: 14-18. Retrouver la guerre, Paris 2000: Gallimard.

- Audoin-Rouzeau, Stéphane / Becker, Jean-Jacques (eds.): Encyclopédie de la Grande Guerre, 1914-1918. Histoire et culture, Paris 2004: Bayard.

- Beaupré, Nicolas: Les grandes guerres, 1914-1945, Paris 2012: Belin.

- Beaupré, Nicolas: La France en guerre, 1914-1918, Paris 2013: Belin.

- Becker, Jean-Jacques: Les Français dans la Grande Guerre, Paris 1980: R. Laffont.

- Becker, Jean-Jacques / Krumeich, Gerd: La grande guerre. Une histoire franco-allemande, Paris 2008: Tallandier.

- Cabanes, Bruno: La victoire endeuillée. La sortie de guerre des soldats français, 1918-1920, Paris 2004: Seuil.

- Doughty, Robert A.: Pyrrhic victory. French strategy and operations in the Great War, Cambridge; London 2008: Harvard University Press.

- Ducasse, André / Meyer, Jacques / Perreux, Gabriel et al.: Vie et mort des français, 1914-1918. Simple histoire de la grande guerre, Paris 1962: Hachette.

- Duroselle, Jean Baptiste: La Grande guerre des français, 1914-1918. L'incompréhensible, Paris 2002: Perrin.

- Feiertag, Olivier: La déroute des monnaie, in: Audoin-Rouzeau, Stéphane / Becker, Jean-Jacques (eds.): Encyclopédie de la Grande Guerre, 1914-1918. Histoire et culture, Paris 2004: Bayard, pp. 1163-1176.

- Fogarty, Richard: Race and war in France. Colonial subjects in the French army, 1914-1918, Baltimore 2008: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Hanna, Martha: Your death would be mine. Paul and Marie Pireaud in the Great War, Cambridge; London 2008: Harvard University Press.

- Loez, André: 14-18, les refus de la guerre. Une histoire des mutins, Paris 2010: Gallimard.

- Maurin, Jules: Armée, guerre, société, soldats languedociens, 1889-1919, Paris 1982: Publications de la Sorbonne.

- Pourcher, Yves: Les jours de guerre. La vie des Français au jour le jour entre 1914 et 1918, Paris 1994: Plon.

- Prost, Antoine / Winter, Jay: Penser la Grande Guerre. Un essai d'historiographie, Paris 2004: Seuil.

- Purseigle, Pierre: Mobilisation, sacrifice et citoyenneté. Angleterre-France, 1900-1918, Paris 2013: Les Belles Lettres.

- Renouvin, Pierre / Prost, Antoine: L'armistice de Rethondes, 11 novembre 1918, Paris 2006: Gallimard.

- Saint-Fuscien, Emmanuel: À vos ordres? La relation d'autorité dans l'armée française de la Grande guerre, Paris 2011: Editions de l'École des hautes études en sciences sociales.

- Smith, Leonard V. / Audoin-Rouzeau, Stéphane / Becker, Annette (eds.): France and the Great War, 1914-1918, Cambridge; New York 2003: Cambridge University Press.

- Thébaud, Françoise: La femme au temps de la guerre de 14, Paris 1986: Stock; L. Pernoud.