Preliminaries↑

By late 1914, the mobile campaigns of the war’s first two months on the Western Front had given way to positional warfare. Determined to break the stalemate and expel German armies from French soil, General Joseph Joffre (1852-1931), the French army’s commander-in-chief, directed his forces to mount two concentric offensives against the German defensive line. Together they sought a rupture (percée) of the German defenses.

The first offensive would take place in the Artois region, north of Paris. The second would strike German positions in Champagne, east of the French capital. Together, the two offensives would simultaneously target both shoulders of the Noyon salient, the great bulge of German-occupied territory protruding toward Paris. The operations’ ultimate objective was to break through the front, dislodge the Germans from their increasingly elaborate field fortifications, and force them to fight in the open, where the superior élan and offensive spirit of the redoubtable French poilu would inflict a decisive defeat on the invaders.

First Battle of Champagne (20 December 1914 - 20 March 1915)↑

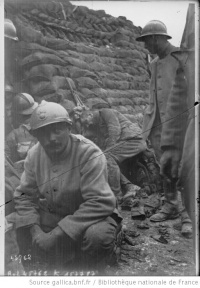

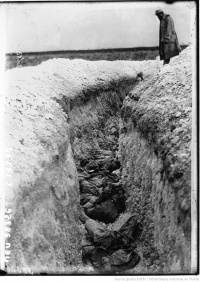

French forces in Champagne implemented Joffre’s strategic design on 20 December 1914, when the French Fourth Army, commanded by General Fernand de Langle de Cary (1849-1927) attacked German positions on a thirty-kilometer front. Supported by the fire of nearly 700 guns, the attacking infantry established footholds in the first line of German defenses. Further progress proved difficult in the face of fierce German counterattacks, bad weather, and defective artillery ammunition. The last of these factors proved especially troublesome, with faulty shells exploding prematurely in the breeches of French guns, or failing to inflict significant damage on German positions. Over the next few weeks, the French continued to launch additional attacks, but none managed to defy the pattern of the offensive’s first phase. Langle suspended the attacks in mid-January to take stock of the situation and process the lessons of the previous weeks’ fighting. When the offensive resumed on 16 February, the attackers enjoyed an even greater preponderance of artillery, which sought not only to provide a powerful preliminary bombardment, but to synchronize its fire with the infantry’s advance throughout every phase of an assault. Nevertheless, the offensive once again ran out of steam in the face of stiff German resistance and the attackers’ inability to subject the entire defensive system to a simultaneous attack throughout its depth. Notwithstanding Joffre’s insistence on repeated attacks and Langle’s efforts to implement tactical methods that emphasized a high degree of co-operation between artillery and infantry, the desired breakthrough failed to materialize. On 20 March, the French high command called the operation off. In exchange for a total of 93,000 dead, wounded, or missing soldiers, the Fourth Army had captured approximately five square kilometers of ground.

Second Battle of Champagne (25 September 1915 - 14 October 1915)↑

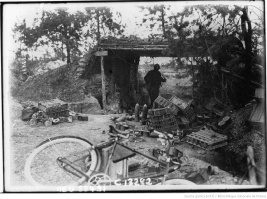

Undaunted by the failure of the Fourth Army’s efforts in early 1915, Joffre continued to identify Champagne as the optimal place for breaking through German defenses. While breakthrough remained an aspirational goal, a new offensive in Champagne would reflect Joffre’s strategic emphasis on wearing down German resources through the process of “nibbling” (grignotage) of German materiel and reserves. After extensive preparations that lasted for much of the summer, the Second Battle of Champagne began on 25 September. Its opening was timed to coincide with a secondary attack that French forces launched in Artois on the same day. The Champagne operation represented the French army’s greatest effort of the war thus far. Nearly half a million men from General Edouard Castelnau’s (1851-1944) Center Army Group, supported by over 2,000 artillery pieces, attacked German positions along a thirty-kilometer wide front following an intense artillery bombardment that lasted three days. By the end of the first day, they succeeded in breaking through the German first line, and captured a twelve-kilometer wide stretch of the enemy’s forward defenses. As soon as the French advance came into the proximity of the second line, the attack began to run out of steam. It was the old story: capturing enemy positions was easier than sustaining a steady momentum of advance. The persistent weakness of French heavy artillery, reflected in an overreliance on the 75 mm field piece, compounded the problem. In the days that followed, the offensive increasingly assumed the form of relatively small, poorly co-ordinated attacks against individual objectives that lacked broader operational coherence. Unfounded rumors of a breakthrough on the night of 28-29 September spurred the French high command to feed additional units into the battle, to no avail. The commitment of more troops merely exacerbated the organizational confusion on the battlefield, and contributed to the skyrocketing casualties, which reached a total of over 62,000 by the end of the offensive. Sporadic fighting continued for another two weeks, with Joffre terminating the offensive on 14 October. The French had captured significant numbers of prisoners – some 18,000 in the first four days alone – in addition to over 100 German guns, but they failed to substantially alter the strategic situation on the Western Front.

Aftermath↑

The failure of the Second Battle of Champagne marked the end of the region’s role as the French high command’s main strategic focus. Henceforth, the war’s center of gravity shifted to other sectors of the front, most notably Verdun, Flanders, and the Chemin des Dames. For the next two years, the old battlefields of Champagne served as one of the Western Front’s “quiet sectors,” where battle-weary units would be sent to rest and reorganize after intense combat elsewhere. In the final weeks of the war, Champagne once again became the scene of severe fighting when the French Fourth Army, now commanded by General Henri Gouraud (1867-1946), finally succeeded in breaking through the German defenses and advancing toward Sedan as part of the war-winning Allied offensives of September-November 1918.

Sebastian Lukasik, United States Air Command and Staff College

Section Editor: Emmanuelle Cronier

Selected Bibliography

- Doughty, Robert A.: Pyrrhic victory. French strategy and operations in the Great War, Cambridge; London 2008: Harvard University Press.

- Greenhalgh, Elizabeth: The French army and the First World War, Cambridge 2014: Cambridge University Press.

- Humphries, Mark Osborne / Maker, John (eds.): Germany's Western Front. Translations from the German official history of the Great War. 1915, volume 2, Waterloo 2009: Wilfrid Laurier University Press.

- Ministère de la Guerre, Etat-Major de l’Armée: Les armées françaises dans la Grande Guerre. La stabilisation du front, les attaques locales (14 novembre 1914-1er mai 1915), volume 2, Paris 1931: Imprimerie nationale.

- Ministère de la Guerre, Etat-Major de l’Armée: Les armées françaises dans la Grande Guerre. Les offensives de 1915, l'hiver 1915-1916 (1er mai 1915-21 février 1916), volume 3, Paris 1926: Imprimerie nationale.