Introduction↑

Perhaps nothing symbolizes warfare on the Eastern Front in World War I more than book titles such as Winston Churchill’s (1874-1965) The Unknown War or Sir John Wheeler-Bennett’s (1902-1975) The Forgotten Peace, his study on the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. The 1917 Russian Revolution, the rise of the Bolsheviks and the West’s decision to ignore the infant Soviet Republic at Versailles combined to relegate World War I’s Eastern Front to an “unknown” and “forgotten” status. For the purposes of this article the Eastern Front will be defined as those areas where the Imperial Russian Army fought the Germans and their main ally the Austro-Hungarians. Warfare in the east featured long periods of prolonged battles that included large-scale manoeuvres and ultimately movement that military leaders and soldiers in the west could only envy. As in the west, industrial capabilities combined with emerging technologies produced weapon systems with rapid fire capabilities that were little understood in terms of their military effectiveness and would handicap military leaders who did not foresee or accept the heightening lethality of the battlefield.

The irony of World War I in the east being an “unknown war” resolved by a “forgotten peace” is that the three Empires - Romanov, Habsburg and Hohenzollern - fought a brutal conflict for control over the territory that is now defined as Eastern Europe and in the end, none of the empires existed. Moreover, in the wake of the collapse of the monarchies that had long controlled the territories in question, independent nations emerged that featured a variety of political franchises. In addition, focus on the war of movement gave rise to the birth of the idea of Blitzkrieg in German operational thinking.[1] Perhaps more appropriately, military technology’s impact on the Eastern Front became more of a question of supply than of how best to use this equipment at a strategic, operational and tactical level. Another significant characteristic of Eastern Front warfare was the role of each coalition: the Entente persistently sought to coordinate planning to strike a decisive blow while the Central Powers moved German troops from theater to theater, staving off one defeat-threatening disaster after another.

Opening Battles↑

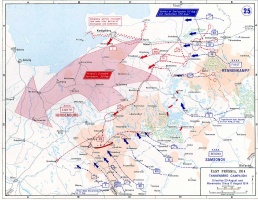

While Imperial Germany deployed slightly under 1 million men in their invasion of France, inspired by Count Alfred von Schlieffen’s (1833-1913) war plan, war exploded across the borderlands of Imperial Germany, Russia and Austria-Hungary in August 1914.[2] A central premise of Germany’s war plan was that it would take the Russians six weeks to mobilize their notorious “steam roller.” But, as is well known, the Russians invaded East Prussia fifteen days after mobilization out of respect for their treaty obligations with France. The ensuing battles of Tannenberg and Gumbinnen culminated in the destruction of the Russian 2nd Army and a decisive victory for the Germans. These battles featured such rapid movement of troops, first by the Russians into East Prussia, and then by the Germans as they moved precious but limited assets with the aid of aerial reconnaissance from the front of the 1st Russian Army to engage the 2nd Russian Army. The rapid pace of the battles outstripped the ability of command elements in the Russian army to control the movement of the armies in the field. For the Russians, open communications was the least of their problems. The unknown whereabouts of the Germans and the failure of the front commander General Iakov Gregor‘evich Zhilinskii (1853-1918) to coordinate operations between his two armies caused the disastrous outcome of this operation.

On the German side, first the commander General Maximilian von Prittwitz (1848-1917) panicked and threatened to retreat behind the Vistula, effectively surrendering East Prussia to the Russians. Helmuth von Moltke the Younger (1848-1916), commander in chief of the Germans and deeply engaged in an attempt to preserve the integrity of the invasion of France, responded to this situation by first sending two army corps from France to the east and then relieving von Prittwitz of his command. Fortunately for the Germans, von Prittwitz’s chief of staff Max Hoffmann (1869-1927) ascertained that the 1st Russian Army under the command of General Paul von Rennenkampf (1854-1918) had halted in place so that he could deploy a light cavalry screen in front of it. In a logistical feat, the bulk of all German forces in East Prussia were transferred to the south where they quickly and surprisingly enveloped and annihilated the Russian 2nd Army under the command of General Aleksandr Vasil’evich Samsonov (1859-1914).[3] In the end, with the 2nd Army destroyed, the Germans were overwhelmed with Russian prisoners of war (POWs) - something for which there was no planning. More importantly, the decisive German action in East Prussia bought them time to resolve their situation in France before considering their next step on the Eastern Front.

In the aftermath of this debacle, efforts were made to blame Rennenkampf for not supporting Samsonov - even worse, much innuendo emerged claiming that personal animosity dating back to the Russo-Japanese War existed between the two commanders. No such evidence exists and, in fact, Rennenkampf had been forced to halt because he had outrun his supply lines. Even worse, Zhilinskii had lost control of the situation and then failed to alert Samsonov to the status of Russia’s 1st Army. For the Russians, the failure of its high command elements to work in unison with commanders in the field resulted in command and control shortcomings: officers did not follow orders and conduct operations as they best saw fit. In the end, Russian army groups of all sizes did not support each other in the midst of battle. This would define the operational conduct of the Tsar’s army throughout the war.[4]

Nonetheless, the Russians were able to endure the defeat in East Prussian as they soon launched a major operation against the Austro-Hungarians in Galicia. In the aftermath of the disaster in East Prussia, Nikolai Nikolaevich, Grand Duke of Russia (1856-1929), commander in chief of the Russian army, ordered his second offensive operation. Before the war the Russians had planned two major offensive operations that were not designed to support each other and ultimately moved in two different directions - one to the northwest, the other to the southwest. However, in Galicia, the Russians mobilized four instead of two armies and launched their offensive twenty-four days after mobilization. Perhaps the saving factor for the Russians in all of this was that the Austro-Hungarians, with arguably the weakest army among the Great Powers, did exactly the same thing. Namely, under the leadership of Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf (1852-1925), the Austrian commander in chief, divided his forces between defending Austrian Galicia and invading Serbia.

Once the Schlieffen plan had run its course and while the “race to the sea” occurred on the Western Front, the Germans redirected their attention to the Eastern Front. Between early September and the end of 1914, the Germans dislodged the Russians from East Prussia in the Masurian Lakes campaign and then unsuccessfully attempted to remove the Russians from their share of partitioned Poland through a campaign that culminated in the Battle of Łodz. As became the custom throughout the war, the Germans also provided additional troops to the Austro-Hungarians to stabilize the Galician front while the Serbians stubbornly and tenaciously defended their nation.[5] In addition, after the opening rounds of battles in the east, whether rightly or wrongly, the names Paul von Hindenburg (1847-1934) and Erich Ludendorff (1865-1937) would forever be inscribed in the pantheon of German heroes.[6]

Fall/Winter/Spring, 1914-1915↑

While the situation on the Western Front devolved into a stalemate and a Christmas truce, nothing of the sort occurred on the Eastern Front. The sheer expanse of the Eastern Front, which ranged from the Baltic to the Black Sea and covered over 1,600 miles, distinguished it from the Western Front. The most significant difference between the two fronts, however, rested in manpower. Simply put, regardless of the 12 million men that Russia ultimately mobilized over the course of World War I, there were never as many men per square mile on the Eastern Front as there were in the west. As the fall of 1914 approached, the Russians did not relent in their efforts to sweep the Austro-Hungarian army out of Galicia, break through the Carpathian mountain barrier and sweep into the Hungarian plain. By mid-September the four armies under the command of General Nikolai I. Ivanov (1851-1919) had pushed the Austro-Hungarian army back over 100 miles, thus forcing them to retreat to the base of the Carpathian Mountains.

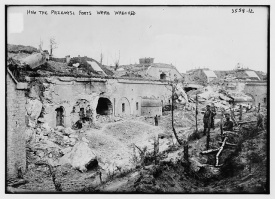

This set the stage for the first major siege of World War I at the fortress Przemysl in the southeast corner of Austrian Galicia. Here the Russian Third Army, under the command of General Radko Dimitriev (1859-1918), would envelop the over thirty fortified positions of this fortress network and lay siege to the city/fortress beginning 24 September 1914. The Russians retreated behind the river San in mid-October to wait for the offensive Hindenburg had launched against Warsaw to run its course but, more importantly, to provide time for the quartermaster to resupply the operational army with artillery shells. The siege would resume at the end of October 1914 and would continue throughout the winter until the Austrians finally capitulated on 22 March 1915. Up until this point in the war the Russians had demonstrated that their supply and transportation problems were monumental which had a direct impact on their ability to conduct operations in a timely manner. For the Austrians, the situation was far more critical - from the outbreak of the war until the spring of 1915, the Austro-Hungarian army had absorbed huge losses (ultimately the Austrian army would suffer at least a 75 percent loss rate of the total number of men mobilized - the highest loss rate of any WWI belligerent) from which the army never recovered and which made the security of their empire precariously dependent on German support.[7]

The Great Retreat↑

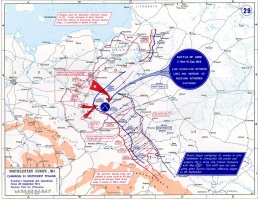

Before the Russians could concentrate the forces needed to threaten the heart of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Germans launched what was planned to be a minor offensive from Gorlice-Tarnow just northwest of Przemysl. This plan was approved after French operations on the Western Front stalled and the British launched their ill-fated operation at Gallipoli. After a tremendous struggle with Erich von Falkenhayn (1861-1922), the new German Chief of Staff (von Moltke was relieved of duty after the Schlieffen plan failed), Hindenburg and Ludendorff finally got authorization to conduct an operation on the Eastern Front.

On 2 May 1915, the Central Powers under Germany’s leadership using a newly formed army composed of some 160,000 soldiers and 600 heavy and light artillery pieces launched the Gorlice-Tarnow offensive. Under the command of General August von Mackensen (1849-1945), an old Cavalry General and his Chief of Staff Hans von Seeckt (1866-1936), the German Eleventh Army broke through and created a forty mile gap in the Russian line. General Dimitriev’s Third Army of approximately 60,000 men and 150 artillery pieces was all that stood in front of this assault. A four-hour artillery barrage decimated Russia’s front line defenses and, without effective counter fire or secondary lines of defenses, the Central Powers over-ran them. Lacking heavy artillery capability the three Russian armies in Galicia were overwhelmed. The Russians had to evacuate Przemysl, surrender Lemberg (Lviv) on 22 June and ultimately evacuate Warsaw on 5 August. By the end of August, the Eastern Front now ran from Lithuania to Romania denoting that the Central Powers had captured the entire Polish salient.[8]

The Russian response to this disaster was Nicholas II, Emperor of Russia’s (1868-1918) decision to transfer his cousin the Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolaevich to the Caucasus front and take over command of the army himself. Though Nicholas II effectively gave command of his army to his General Staff, he would from this time forward be considered responsible for the success and more frequent failures of the army. Even worse, Nicholas II could not both command the army and run his government effectively; the impact of this decision would become clear in February 1917 when the Tsar lost his crown.[9] The Germans, on the other hand, enjoyed a great victory by massing troops and artillery at a fixed point. Yet, even a large-scale breakthrough failed to win the war. As with many great armies of the past, what the breakthrough of 1915 revealed to the Germans was Russia’s endless landscape.[10] In addition, it exhibited that the Russian army had a tradition of retreating in good order that dated at least back to the age of Napoleon I, Emperor of the French (1769-1821) and was most recently practiced during the Russo-Japanese War. Nonetheless, as the winter of 1915-16 gripped the Eastern Front, the Russian army was been pushed back and battered; it did not present an imminent threat to the sovereignty of the Habsburgs, Hohenzollerns or the territorial integrity of their respective empires.

1916↑

The steady escalation of the war throughout 1915 included Italy declaring war on the Central Powers, Bulgaria joining the Central Powers after the Gallipoli campaign and the success of the German breakthrough at Gorlice-Tarnow. Entente planning for 1916 featured an all-out combined offensive designed to defeat the German army on the Western Front. The Germans compromised these plans when they launched their attack on Verdun in February. From that point on, the most salient feature of 1916 was France's appeal to its British and Russian allies to launch some type of counter operation that would give them relief. The Germans and Austrians underestimated the capabilities of the Russian army, believing that the devastation of 1915 had rendered it incapable of offensive operations and they were not too far off in their estimation. What they could not know was that General Aleksei Alekseevich Brusilov (1853-1926) was not going to accept a lack of munitions as an excuse for not conducting offensive operations. While Nicholas II was Commander in Chief of the army, his Chief of Staff General Mikhail Vasil’evich Alekseev (1857-1918) was the main force behind all operational decisions. Alekseev was opposed to any major operations in 1916 because of supply shortages. Being a disciple of orthodox military doctrine, he believed that any offensive operation should feature a prolonged artillery bombardment concentrated in one spot in order to cause a major breakthrough such as the Germans accomplished the previous year. Without heavy artillery, Alekseev was opposed to any operations in 1916 regardless of the urgency of French appeals.[11]

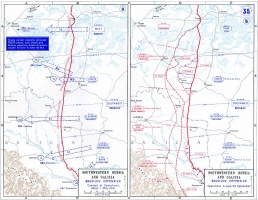

General Brusilov, however, being in command of the southwest front realized that the Austrians had transferred large numbers of forces in April and May aimed for what became their summer Italian offensive which commenced in Trentino on 15 May 1916. More importantly, Brusilov believed that the concentration of forces in one spot and the saturation of the terrain with a massive artillery bombardment served to alert the enemy to the pending offensive operation. Choosing surprise, and without the endorsement of the Stavka (the Russian High Command), Brusilov launched his offensive on 4 June. His plan of invading Galicia with four armies, at least at the beginning, worked spectacularly. He was able to take back much of the territory lost in Galicia in 1915 and once again threaten to re-occupy Lemberg as Austrian units around Lutsk, Bukovina and Ocna collapsed, prompting widespread retreat along the entire front.[12]

While enjoying great initial success, the offensive ran out of steam for three reasons: 1) As General Alekseev foresaw, the army did not have the supply base to provide the munitions Brusilov needed to exploit his initial successes. 2) In addition to material shortages, by the beginning of July, it also became clear to Brusilov that the Stavka was not going to provide reinforcements of any type to the ranks which were rapidly depleted by operational loses. 3) The old problem of commanders in the field refusing to support each other and the High Command's lack of ability to change this situation. In this case, Generals Aleksei Evert (1857-1926) and Aleksei Nikolaevich Kuropatkin (1848-1925) to the north refused to launch diversionary operations, claiming they could not do so due to the conditions of their respective armies. As a result, the Germans had a free hand to move forces from the north to the south and, in late July, the Germans re-enforced the Austro-Hungarian forces. The tide of battle shifted and the Russians, while once again seemingly in a position to knock the Danubian monarchy out of the war, failed to gain their strategic objectives. In fact, the outcome of the Brusilov offensive for the Russians was another retreat from Galicia. Nonetheless, the Brusilov offensive did bring relief to the French, arguably saved the Italians from complete collapse and finally convinced the Romanians to declare war on the Central Powers. Of even greater magnitude, the Austro-Hungarian army never recovered from the losses incurred during the Brusilov offensive thus rendering their military forces weak, indeed impotent, for the rest of the war.[13] Another and perhaps the greatest consequence of the Brusilov offensive was that Francis Joseph I, Emperor of Austria (1830-1916) finally agreed to the German demand to unify the Eastern Front command under their leadership in the months immediately leading up to his death in December 1916. This decision came in time for the Germans to organize a multi-national campaign that would sap the military strength of Romania, making it an additional burden on the Russians. On paper, Romania appeared to be a good ally because of the 600,000 strong army. In fact, the Romanian army was poorly trained, badly supplied and not capable of independent operations. Their declaration of war coincided with the dismissal of Erich von Falkenhayn as Chief of the German General Staff. Seeking to restore his reputation, he successfully lobbied to command the Central Power’s force in its invasion of Romania once the Brusilov offensive had been contained. With an international force consisting of German, Austrian, Bulgarian and Turkish troops, von Falkenhayn indeed invaded and routed the Romanian army. By the end of the year, Romania, save for the territory of Moldavia, was completely occupied and the Imperial Russian army had another 700 kilometers of front to defend.[14]

1917: The Russian Revolution and the End of World War I in the East↑

Ironically, as the 1917 Russian revolution forced Nicholas II to abdicate in February, the Eastern Front was settling into a static war of attrition as the semblance of a unified trench network, a network comparable to that on the Western Front, started to cover the entire length of the front. While some arguments posit that the Russian army was prepared to have its best campaign of the war in 1917 because the question of supplies had largely been resolved, such a conclusion overlooked other salient concerns: most prominently, the war-weariness that ultimately compromised the morale of the troops in the field. The collapse of the morale of the soldiers in the Russian army resulted in the Great Mutiny of February 1917 which directly contributed to Nicholas II’s decision to abdicate at the beginning of March 1917.[15] The old army would have its last gasp in the form of the June 1917 offensive aimed at keeping Russia in the war, building support for the infant provisional government in Petrograd and conquering all of Galicia once and for all. What this action demonstrated, however, was that Imperial Russian armed forces, much like the Austro-Hungarian’s at this stage of the war, no longer had any fighting capability. With this fact vividly exhibited in the failure and defeat of Russian arms, a path opened for the Bolsheviks to seize power in October 1917. The Bolsheviks followed through with one of their most basic promises and immediately sued for peace, which started a process that culminated in the signing of the treaty of Brest-Litovsk on 3 March 1918 ending the conflict between Russia, now known as the Russian Soviet Federal Socialist Republic and the Central Powers.[16]

Conclusion↑

The enormous size of the Eastern Front allowed mobility to characterize warfare there. The size of the front also proved to limit the effectiveness of every major military operation.[17] To put it another way, be it the German breakthrough in 1915 or the Brusilov offensive in 1916, hugely successful mobile operations ultimately failed to achieve their strategic objectives because each respective army ran out of the men and materials needed to continue the offensive until their enemy was completely defeated. Complicating and always contributing to material shortages was the never-ending commitment to operations on different fronts, which in some cases, were not even remotely connected to each other. Each belligerent suffered from this fact - the Austrians by 1916 were waging a war against the Italians in the Alps while fighting the Russians in Galicia. The Germans always had to consider the Western Front before doing anything in the east. Hence, while the Germans saved the Austro-Hungarians from the threat of the Brusilov offensive, they also were engaged in heavy combat both at Verdun and on the Somme.

All belligerents also struggled with command issues both within their central commands as they endeavored to determine where to apply resources (Eastern or Western Front or somewhere else), and especially at the operational level where Army and unit commanders often did not support each other when engaged in battle. Ultimately, neither side prevailed on the Eastern Front due to its vastness. In the end, revolution in Russia, dire material shortages for the Austro-Hungarians and the German need to concentrate all resources on the Western Front brought about the end of the Eastern Front. However, because of the overthrow of the Romanovs, the disintegration of the Habsburg monarchy and the final defeat of the Germans, warfare that included the brutal Russian Civil War and the Polish-Soviet War would continue on the Eastern Front until the Treaty of Riga on 18 March 1921. The signing of this treaty ended the cycle of conflict that began in August 1914.

John W. Steinberg, Austin Peay State University

Section Editors: Boris Kolonit͡skiĭ; Nikolaus Katzer

Notes

- ↑ See Barrett, Michael B.: Prelude to Blitzkrieg. The Austro-German Campaign in Romania, Bloomington 2013, pp. 306-314.

- ↑ The collection of essays to consult on the topic of war plans is Hamilton, Richard F. and Herwig, Holger H.: War Planning 1914, New York 2010, pp. 1-143 and 226-257.

- ↑ See Showalter, Dennis: Tannenberg Clash of Empires, Hamden 1991 for the best study of the East Prussia campaign of August 1914.

- ↑ Nikolai Nikolaevich Golovin (1875-1944), a pre-war Russian General Staff Officer wrote an in-depth study of this campaign in the 1920s that can still be read with great profit. See Golovin, Nikolai Nikolaevich: The Russian Campaign of 1914; The Beginning of the War and Operations in East Prussia, Fort Leavenworth 1933.

- ↑ See Airapetov, Oleg Rudol’fovich: Uchastie Rossiiskom Imperii v Pervoi Mirovoi Voine (1914-1917) Tom I 1914 rod. Nachalo [The Participation of the Russian Empire in World War I (1914-1917) Volume I 1914. The Beginning], Moscow 2014, pp. 89-187.

- ↑ Herwig, Holger H.: The First World War: Germany and Austria-Hungary, 1914-1918, London 2014, pp. 78-97.

- ↑ On the siege of Przemysl and the first winter of the war, see Stone, Norman: The Eastern Front 1914-1917, New York 1998, pp. 92-121 and Tunstall, Graydon A.: Blood on the Snow. The Carpathian Winter War of 1915, Lawrence 2010.

- ↑ See Rostunov, I.I.: Russkii Front Pervoi Mirovoi Voiny [The Russian Front during the First World War], Moscow 1976, pp. 233-247.

- ↑ On the situation with Russia’s high command see Airapetov, Uchastie Rossiiskom Imperii v Pervoi Mirovoi Voine (1914-1917) [The Participation of the Russian Empire in World War I (1914-1917)] 2014, pp. 159-213.

- ↑ DiNardo, Richard L.: Breakthrough: The Gorlice-Tarnow Campaign, 1915, Santa Barbara 2010.

- ↑ Stone, Norman: The Eastern Front 1914-1917, New York 1998, pp. 232-235. It should also be noted that other commentators view Alekseev’s role in 1916 as critical to the success of the Brusilov offensive once it was launched. See: Nelipovich, S.G.: Brusilovskii Proryv. Nastuplenie Iugo-Zapadnogo Fronta v Kampaniiu [The Brusilov Breakthrough: The Conduct of the Offensive on the South-Western Front], Moscow 2006, pp. 57-65. Regardless of his direct role in the Brusilov Offensive, Alekseev was the military professional on whom Nicholas II depended for advice and successful operations from the time Nicholas II assumed command of the army until his abdication.

- ↑ Dowling, Timothy C.: The Brusilov Offensive, Bloomington 2008, pp. 62-88.

- ↑ Rothenberg, Gunther E.: The Army of Francis Joseph, West Lafayette 1976, pp. 201-219.

- ↑ Torrey, Glenn E.: The Romanian Battlefront in World War I, Lawrence 2011, pp. 45-170.

- ↑ For the situation in 1917 and especially the role of women in the military, see Stoff, Laurie: They Fought for the Motherland: Russia's Women Soldiers in World War I and the Revolution, Lawrence 2006.

- ↑ On the military situation in Russia in 1917, see Wildman, Allan K.: The End of the Russian Imperial Army, 2 vols., Princeton 1980/1987.

- ↑ Gatrell, Peter: Russia's First World War: a Social and Economic History, Harlow 2005, pp. 243-277.

Selected Bibliography

- Airapetov, Oleg Rudol’fovich: Uchastie Rossiiskom Imperii v Pervoi Mirovoi Voine (1914-1917) (The participation of the Russian Empire in World War I (1914-1917)), 2 volumes, Moscow 2014: Universitet Knizhnyi Dom.

- Barrett, Michael B.: Prelude to Blitzkrieg. The 1916 Austro-German campaign in Romania, Bloomington 2013: Indiana University Press.

- Churchill, Winston: The unknown war. The Eastern Front, New York 1931: C. Scribner's Sons.

- DiNardo, Richard L.: Breakthrough. The Gorlice-Tarnów campaign, 1915, Santa Barbara 2010: Praeger.

- Dowling, Timothy C.: The Brusilov offensive, Bloomington 2008: Indiana University Press.

- Gatrell, Peter: Russia's First World War. A social and economic history, Harlow 2005: Pearson/Longman.

- Golovin, N. N. / Muntz, Arthur Godfrey Stephens: The Russian campaign of 1914. The beginning of the war and operations in East Prussia, Fort Leavenworth 1933: Command and General Staff School Press.

- Hamilton, Richard F. / Herwig, Holger H. (eds.): War planning 1914, Cambridge; New York 2010: Cambridge University Press.

- Herwig, Holger H.: The First World War. Germany and Austria-Hungary, 1914-1918, London; New York 1997: Arnold; St. Martin's Press.

- Nelipovich, S. G.: Brusilovskii Proryv. Nastuplenie Iugo-Zapadnogo Fronta v Kampaniiu (The Brusilov breakthrough. The conduct of the offensive on the South-Western front), Moscow 2006: Tseikhgauz.

- Rostunov, Ivan Ivanovich: Russkii front pervoi mirovoi voiny (The Russian Front during the First World War), Moscow 1976: Nauka.

- Rothenberg, Gunther E.: The army of Francis Joseph, West Lafayette 1976: Purdue University Press.

- Showalter, Dennis: Tannenberg. Clash of empires, Dulles 2004: Potomac Books Inc..

- Stoff, Laurie: They fought for the motherland. Russia's women soldiers in World War I and the revolution, Lawrence 2006: University Press of Kansas.

- Stone, Norman: The Eastern front, 1914-1917, London; Sydney; Toronto 1975: Hodder and Stoughton.

- Torrey, Glenn E.: The Romanian battlefront in World War I, Lawrence 2011: University Press of Kansas.

- Tunstall, Graydon A.: Blood on the snow. The Carpathian winter war of 1915, Lawrence 2010: University Press of Kansas.

- Wheeler-Bennett, John W.: Brest-Litovsk. The forgotten peace March 1918, New York 1971: Norton Library.

- Wildman, Allan K.: The end of the Russian imperial army, 2 volumes, Princeton 1980-1987: Princeton University Press