The Difficult Creation of a War Celebration (1918-1922)↑

Ambivalences and Interpretations of the Victory↑

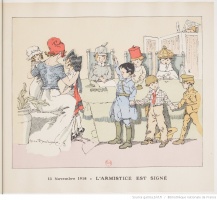

As soon as the ceasefire was declared, people were overcome with joy and relief. This ambivalence, in which the joy of the victory against the enemy was weakened by the relief at the prospect of the end of hardship, highlights the ambiguous aspect of the celebration of the end of the war and thus of the date 11 November in France and elsewhere.[1] As a matter of fact, tension arose between the veterans and the republican power which was eager to celebrate the regime’s victory and its values but also the idea of revenge. The war’s survivors were, in fact, disgusted by the slaughter, the misguidance of their leaders, the gap between those at the front and those at the rear and the perceived nonsense of the conflict. For these wounded, traumatized men, celebrating the victorious triumph of one army or regime over another was unthinkable. Of course, the mission had been fulfilled, the lost provinces recovered, the “German ogre”[2] laid down. But, the cost was so high that is was only bearable in so far as it could be seen as the war to end all wars, if the respect towards the sufferings of the soldiers was absolute and if grief came before misplaced vanity.

The Difficult Creation of a National Holiday↑

The authorities quickly engaged in the task of creating a commemorative holiday knowing they had to take into account the nearly 5 million veterans, the “spirituality of the trenches”[3] (as Annette Becker has termed it) and the grief affecting each family. In addition, the country had in fact been reflecting since 1915, along with Jean Ajalbert (1863-1947), on a “permanent reminder of the war victims.”[4] Georges Clémenceau (1841-1929) explained as early as the armistice that “it was paramount to create, in the French Republic, a celebration in their (the soldiers’) honor.”[5] It took over four years of harsh discussions between the state, keen on celebrating the victory of its army and its ideology, and the veterans longing for a silent celebration of their hatred of all wars to see the outcome of the project. The commemoration was first due to be held on 1 and 2 November then was paired up in 1920 with the 50th anniversary of the Republic and the tribute to Léon Gambetta (1838-1882). It was then postponed to 13 November 1921, without it being a bank holiday so as not to hamper reconstruction. As a consequence of the strong reaction of veterans, who were much attached to the symbolic day of 11 November and decided to boycott the celebrations, a compromise was embedded by the law of 21 October 1922, launching the proceedings which were to last until 2011.

The celebration, now a bank holiday, although it did not fall under the church and state separation law of 1905, was founded on the cult of the flame of remembrance, which was lit under the Arc de Triomphe in 1923 by André Maginot (1877-1932), the Minister of Pensions, as well as on the mourning of and the tribute to the unknown soldier. This new national celebration soon became the country’s own, centered on growing memorial services, the second[6] to be created after WWI. Although its rituals were quickly settled, its significance was still so controversial that the celebration was immediately questioned and used by antagonistic political forces.

Practices and Changes in the Anniversary of the Great War (from 1922 to Today)↑

A Significant and Questionable Ritual↑

The rituals associated with the commemoration of the end of the war were soon settled and the expenses dedicated to the celebration were increasing. The rituals were based on mandatory and crucial phases with a minute of silence instituted as part of the main commemorative ceremony in 1928. To which were added an individual “roll call” of those who died for France, the sound of the death knell, the flagging of the public monuments and ceremonies at memorial sites. Besides these mandatory segments, town authorities remained free to determine the other elements of their ceremonies. In 30 percent of cases, municipal authorities organized religious services thus reintroducing religion into national celebrations, marches leading to memorials, gathering the authorities, civil, musical and military societies, schools and bands.

Military parades were scarce as both the horrors of the war and peace were celebrated. In the capital and the prefectures, it was more common to see the flame to the unknown soldiers lit and parades organized. If the head of states kept silent until 1958, mayors, veterans and teachers often delivered speeches. They spoke of their hatred of the war and aimed to teach children, who were at the heart of these celebrations, the merits of peace among nations. Indeed the ceremonies of 11 November looked more like a peaceful act of pedagogy rather than a glorification of arms and of regime.

Disputes over the celebrations began to grow and incidents occurred in one fifth of all celebrations from 1922 until 1939. The radical right wing leagues argued over its pacifism, naming and shaming the “Jew-ridden Republic.”[7] The communists hammered away at capitalist struggle and clamored for socialism. At the same time, the pacifists, gathered around the memorials, expressed their hatred of all wars. The fights were fierce as the leagues were armed and the communists properly trained and could lead to murder, particularly in the suburbs of Paris.

It was during the Vichy period (1940-1944) that these conflicts reached a climax. The celebration was taken over by members of the resistance as a symbol of the Republic inherited from 1789 as well as by Philippe Pétain (1856-1951) who decided to suppress its status as bank holiday and turned it into an act of contrition of a country dragged to the depths by the corrupted republic.

Mutation and Widening of 11 November↑

After World War II, the celebration was maintained, as before the war but it no longer pertained to WWI only: memories of the resistance and of WWII were mingled in it and blurred its significance. When Charles De Gaulle (1890-1970) came to power in 1958, he delivered a speech, against the will of the veterans, and tried to put the focus of the celebrations on WWI anew. He failed and it was under Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, who would always deliver a speech on this occasion, that the commemorative occasion became a celebration of the dead of all wars in a wider European perspective. Akin to Britain’s Remembrance Day, the French Bleuet de France became a counterpart to the British poppies.

This transformation was not discussed under François Mitterrand’s (1916-1996) left wing government and was fully achieved by Nicolas Sarkozy upon the death of the last of the veterans in 2008. Memories of WWII, the Holocaust, colonial regimes, the experience of civilians, and the executed were now called to mind. The law of February 2012 cemented the transformation and the left wing President François Hollande who presided over the new, seemingly consensual, celebration of 11 November.

Nevertheless, French citizens are turning out in decreasing numbers for the celebration of 11 November. We thus must wonder about maintaining such a celebration in a European and global context and reflect on the anachronistic comparison of all wars, threatening to blur the very message of such a specific anniversary.

Rémi Dalisson, Université/ESPE de Rouen

Section Editor: Alexandre Lafon

Notes

- ↑ Gregory, Adrian: Le 11 novembre dans le Royaume-Uni. In: Histoire culturelle du premier conflit mondial, Péronne 1992, pp. 1517-1523.

- ↑ Grandadam, Emmanuelle: Contes et nouvelles de Maupassant, Rouen and Le Havre 2007, p. 256.

- ↑ Becker, Annette: La guerre et la foi, de la mort à la mémoire, Paris 1994.

- ↑ L’Éveil 16 June 1916. See: Comment glorifier les morts pour la Patrie? Opinions.

- ↑ Clemenceau, Georges: Discours de guerre, Paris 1968, p. 227.

- ↑ The first was the feast of Joan d’Arc (1412-1431) created in 1920.

- ↑ Drumont, Edouard: La France juive, essai d’histoire contemporaine, Paris 1886, pp.vi-xx.

Selected Bibliography

- Dalisson, Rémi: 11 novembre. Du souvenir à la mémoire, Paris 2013: Armand Colin.

- Demiaux, Victor: La construction rituelle de la victoire dans les capitales européennes après la Grande Guerre (Bruxelles, Bucarest, Londres, Paris, Rome), Paris 2013: Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales.

- Jagielski, Jean-François: Le soldat inconnu. Invention et postérité d'un symbole, Paris 2005: Imago.

- Offenstadt, Nicolas: 14-18 aujourd'hui. La Grande Guerre dans la France contemporaine, Paris 2010: O. Jacob.

- Tandonnet, Maxime: 1940, un autre 11 novembre. Étudiant de France, malgré l'ordre des autorités opprimantes, tu iras honorer le soldat inconnu, Paris 2009: Tallandier.

- Theodosiou, Christina: Symbolic narratives and the legacy of the Great War. The celebration of Armistice Day in France in the 1920s, in: First World War Studies 1/2, 2010, pp. 185-198.

- Winter, Jay: Entre deuil et mémoire. La Grande Guerre dans l'histoire culturelle de l'Europe, Paris 2008: Armand Colin.