The First World War as a turning point in European music history↑

The First World War marked the end of the “long 19th century” in music history – the epoch of the civic music culture that began with the Vienna classical period in the latter half of the 18th century and flourished during the Romantic era. Many representative turn-of-the-century composers had either died - Gustav Mahler (1860-1911), Alexander Scriabin (1872-1915), Claude Debussy (1862-1918), and Giacomo Puccini (1858-1924) - or had lost their creative energy - Richard Strauss (1864-1949), Maurice Ravel (1875-1937), Jean Sibelius (1865-1957), Sergei Rachmaninov (1873-1943), etc. In the 1920s, especially in Germany, people spoke of the overnight Bankrott (bankruptcy) of Romanticism and the birth of the neue Musik (new music), which Theodor W. Adorno (1903-1969) insisted in Philosophy of New Music was represented by two contrary tendencies: the twelve-tone technique of Arnold Schoenberg (1874-1951) and the new classicism of Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971).

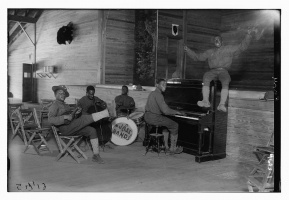

In the post-war era, American popular music influenced aspects of European art music. As early as 1917, black musicians from the “Harlem Hellfighters” infantry division were playing "genuine" jazz in Paris under the direction of James Reese Europe (1881-1919) and causing a great sensation. In the 1920s, American dances such as the Boston and the shimmy became fashionable in Europe. Prominent composers like Ravel, Darius Milhaud (1892-1974), Erwin Schulhoff (1894-1942), Stravinsky, and Paul Hindemith (1895-1963) used idioms of blues and jazz. The birth of the Soviet Union also led to a new phenomenon in music history. Unlike the late national Romanticism of the composers of the Russian Empire, such as Alexander Glazunov (1865-1936), Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov (1844-1908) and Rachmaninov, a satiric-mechanic dryness characterized the experimental avant-garde works of young Soviet composers such as Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975) and Nikolai Myaskovsky (1881-1950).

From the bourgeoisie to the masses: The end of Romanticism↑

From a social perspective, the decline of Romanticism after the war can be understood in terms of the decline of the so-called concert music culture, which had been an institution of the high bourgeoisie. Especially in Germany (since the inflation in 1923) and Austria, many members of high-society had faced financial decline during the war and were forced to abandon their seats, while those who gained wealth during the conflict crowded the subscription concerts and operas. In addition, there was a rapid rise in laborer concerts after the war.

Many young composers and musicians experienced the front lines as soldiers, including Hindemith, Hanns Eisler (1898-1962), Anton Webern (1883-1945), Jacques Ibert (1890-1962), Albert Roussel (1869-1937), Myaskovsky (who suffered shell shock), the pianist Walter Gieseking (1895-1956), the violinist Fritz Kreisler (1875-1962), Paul Wittgenstein (1887-1961) - a pianist and brother of the famous philosopher; he lost his right hand on the Eastern Front - and the conductor Fritz Busch (1890-1951). Schoenberg and Alban Berg (1885-1935) were also drafted into the army, and Ravel became a truck driver at the Verdun front at the age of forty. The distancing from subjectivism that characterized the post-war music of these composers undoubtedly stemmed from their military experiences.

The beginning and end of “the war in music history”↑

Although it is true that the First World War marked a reorientation in music history, in the years leading up to the war music had an anticipatory function as well. Three musical revolutions, which could be metaphorically described as "the war in music history," had already occurred prior to 1914: Schoenberg had composed in the atonal style as early as 1908; Luigi Russolo (1885-1947), an Italian futurist and author of L’arte dei Rumori (The Art of Noises) had experimented with noise music in 1913; Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring, which historian Modris Eksteins considers the symbolic beginning of the war in art history, also premiered in that year. Orchesterstück op. 6,4 (1911) by Anton Webern and "Marsch" from 3 Orchesterstücke op. 6 (1914) by Alban Berg could be also regarded as representing the anticipated violence.

The end of the war in music history did not coincide with the year 1918. Many ideas that had been born during the First World War were not realized until later. For example, although mainly composed during the war, Berg’s Wozzeck, an atonal opera about a poor soldier that reflected the composer’s difficult experiences as a soldier, first premiered in 1925 in Berlin. Moreover, while Schoenberg first described the twelve-tone technique privately to his associates in 1923, the roots of the idea date back to the war. The violent noise in the early works of Hindemith, such as Kammermusik No. 1, Suite 1922 and Sonata for Viola, can also be interpreted as reflections of the composer’s experiences as a soldier. Many musical works from the early 1920s should thus be regarded as belonging to the period of the First World War.

Musical life at home and at the front↑

Soldiers at the front enjoyed music in various ways. They often made instruments such as guitars or violins using helmets, wood, and wire – a kind of trench art. Amateur chorus groups and even orchestras were not uncommon at the front and in prison camps. For example, German captives in Japan performed the premiere of Ludwig van Beethoven’s (1770-1827) Ninth Symphony at the Naruto camp. There were many professional musicians among the soldiers, and they performed table music, serenades, and home concerts, mainly for high-ranking officers; Hindemith even played Debussy’s String Quartet for a group of officers at the front in Belgium.

The phonograph was a special gift for the soldiers at the front. Recorded songs such as It’s a Long Way to Tipperary connected them to their homes. This role of the phonograph – providing music that functioned as an emotional bond between home and the front – was another new development in music history.

On the home front, there was, not surprisingly, a push to exclude music by composers from hostile nations from the repertoire. In England and France, people claimed not to perform Richard Wagner (1813-1883), though it remains difficult to verify this. In Austria, operas by Italian composers such as Puccini were forbidden; Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901), meanwhile, was listed as "Joseph" Verdi on programs. Edward Elgar (1857-1934) composed an extremely patriotic, anti-German oratorio, The Spirit of England. In a further sign of anti-German sentiment, Richard Strauss was made to forfeit the fortune he held in the Bank of England.

The flourishing charity concert was unique to musical life in Germany and Austria during the war. The programs for such events included the national anthem, popular songs, and brilliant orchestral pieces such as Tannhäuser and the Egmont overture. In contrast, the main program of a traditional subscription concert - a high-society institution - had been a symphony. Concerts with symphonies as the main attraction served as a model for the laborer concerts that became prominent in the 1920s.

Concert tours of orchestras, which had been rare prior to 1914, became standard in Austria and Germany during the war. The Austrian government invited the Budapest Philharmonic to Vienna in November 1915, the Orchestra of the Prague Opera in November 1917, the Imperial Orchestra of the Ottoman Turks in January 1918, and the Berlin Philharmonic with Arthur Nikisch (1855-1922) in March 1918. In July 1917, the Vienna Philharmonic toured Switzerland with Felix Weingartner (1863-1942) and performed Hector Berlioz (1803-1869) and Peter Tchaikovsky (1840-1893) along with Beethoven to demonstrate Austria’s cultural openness. However, in Lausanne, near the French border, only works by Beethoven were played, and the concert in Geneva was canceled for political reasons.

Akeo Okada, Kyoto University

Section Editor: Frederik Schulze

Selected Bibliography

- Butler, Christopher: Innovation and the avant-garde, 1900-20, in: Cook, Nicholas / Pople, Anthony (eds.): The Cambridge history of twentieth-century music, Cambridge; New York 2004: Cambridge University Press, pp. 69-89.

- Dahlhaus, Carl: Die Musik des 19. Jahrhunderts. Neues Handbuch der Musikwissenschaft, volume 6, Wiesbaden 1980: Laaber-Verlag.

- Danuser, Hermann: Die Musik des 19. Jahrhunderts. Neues Handbuch der Musikwissenschaft, volume 7, Wiesbaden 1984: Laaber-Verlag.

- Eichhorn, Andreas: Paul Bekker. Facetten eines kritischen Geistes, Hildesheim 2002: Olms.

- Eksteins, Modris: Rites of spring. The Great War and the birth of the Modern Age, Boston 1989: Houghton Mifflin.

- Finscher, Ludwig: Komponieren um 1915, in: Paul Hindemith-Institut (ed.): Hindemith-Jahrbuch, volume 4, Frankfurt a. M. 1977: Schott, pp. 11-28.

- Huybrechts, Dominique: 1914-1918. Les musiciens dans la tourmente. Compositeurs et instrumentistes face à la grande guerre, Mont-de-l'Enclus 1999: Scaldis.

- Riess, Curt: Knaurs Weltgeschichte der Schallplatte, Munich 1966: Knaur.

- Roshwald, Aviel / Stites, Richard (eds.): European culture in the Great War. The arts, entertainment, and propaganda, 1914-1918, Cambridge; New York 1999: Cambridge University Press.

- Stephan, Rudolf: Moderne, in: Blume, Friedrich / Finscher, Ludwig (eds.): Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart. Allgemeine Enzyklopädie der Musik. Meis-Mus, volume 6, Kassel; Stuttgart 1997: Bärenreiter; Metzler.