Introduction↑

On 3 August 1914, German troops began their invasion of Belgium, Germany declared war on France and British Foreign Secretary Sir Edward Grey (1862-1933) pronounced his pondering but ultimately determined speech before the House of Commons, thus preparing the British declaration of war on Germany the next day. At the 39th Street Theater on Broadway in New York City, an audience watched a hilarious and impolite farce, Jocelyn Brandon (1865-1948) and Frederick Arthur’s comedy The Third Party. A review in the New York Times noted the rapid succession of slapstick situations which start in the middle of the First Act when the scene is set in a restaurant:

The contrast between the happy-go-lucky atmosphere on the Broadway stage and the calamitous political and military decisions of the European powers in the first days of what would be called the Great War could not be greater. However, we could certainly imagine some spectator in the 39th Street Theater who was well informed and aware of the historic events taking place in Europe and who sought distraction from the irritating and unsettling news in a rather senseless but powerful comedy. In this respect, the temporal coincidence between the mobilization for war in Europe and the production of a slapstick comedy in New York might highlight one of the most important ambivalences of theatre staged during the First World War in general. There was nearly always a large discrepancy between the world created on stage and the harsh wartime reality outside but, by maintaining this gap, the theatre fulfilled an essential function for the population on the “home fronts” as well as for the soldiers themselves: to provide a space and a brief moment where the grief and sorrow of wartime could be kept outdoors. Nevertheless, and this is not to be seen as a contradiction, all theatrical productions from 1914 to 1918 in the warring countries bear some traces of the war, be it on the level of content or of form and aesthetics. Those plays and entertainments which explicitly staged the war conveyed a certain image of warfare which mostly had nothing to do with the actual experiences of soldiers at the front and only little to do with the hardship of those at the home front.

This article focuses on wartime theatre in the four largest European capitals, London, Paris, Berlin and Vienna which were the leading theatre and entertainment cities of the time period.[2] This article discusses theatrical events and developments on the home front and theatre’s functions for the civilian population as well as for soldiers. This does not imply that there were not lively theatrical activities at and behind the several fronts in the First World War. However, this is a huge and quite distinct field of research which could not simply be treated on the sidelines of this article.[3]

The subsequent sections follow in chronological order and identify key moments in wartime theatre productions that can be found (with slightly divergent emphases) in all four metropolises.

The Last Days of Peace↑

In order to understand the impact the First World War had on the theatre in European cities, we have to be aware of the role theatres played in the first decades of the 20th century in the context of rapid urbanization and growth of the capitals which reached its peak shortly before World War I.

In the European metropolises, live entertainment such as music-hall or variety shows, operettas or comedies, circus or fairground attractions were, from the late 19th century on, a very popular and flourishing part of urban leisure, a prospering sector of cultural production and an essential feature of modern metropolitan life.

In spite of the “theatre crisis” (in terms of profit and of quality) constantly proclaimed from all sides, the presence of theatres of various kinds and the number of spectators probably was never higher than at this moment.[4] Visits to the theatre and other public places of entertainment became increasingly integrated into the everyday life of wide swaths of the population as leisure time became more pervasive. Entertainment theatres were at the epicenter of the establishment of urban mass culture in the European metropolis.[5] These entertainment theatres established strong links throughout Europe and cultural exchange through the circulation of plays, music and artists was very lively. It often only took a few weeks from the staging of a French play in Paris to the premiere of its adaptation in another town. In this sense, the theatres contributed to the building of a specifically urban, cosmopolitan and transnational cultural identity. The identity of the metropolis increasingly competed with the confined and regulated identity of the capital.[6]

Even in the summer months of 1914, there was a wide variety of entertainment available. In London, the big “Anglo-American Exhibition” attracted visitors with models of the Panama Canal, New York with its Skyscrapers and the Grand Canyon or with performances of Wild West Shows, Afro-American bands and the presentation of “Marvels of American and British Arts, Science and Industries.”[7] In Paris, the famous chanson singer Yvette Guilbert (1867-1944) was to be seen on the stage of the long-established café-concert venue L'Alcazar d'Été on the Champs-Élysées[8] which only few days later was closed for good and transformed into a repository for the French Red Cross.[9] In Berlin, the popular Berliner Theater continued the successful run of the operetta Wie einst im Mai (“As once in May”) by Walter Kollo (1878-1940) in which the transformation of Berlin from a quiet provincial capital to a modern metropolis is conveyed by the – ostensibly nostalgic but implicitly progressive – story of three generations of the aristocratic family von Henkeshofen and the working class family Jüterbog which only in the third generation finally find love together. In Vienna, the public visiting the kaiserliche Menagerie, the zoological garden in Schönbrunn, could take a look at the most recent “animal delivery from Northern Africa,” including exotic animals such as jackals, fennecs, Barbary apes, antelopes and dromedaries.[10]

On a political level, these last days of peace brought about both patriotic and pacifist rallies. At the end of July and beginning of August in London and many other big cities in Europe important demonstrations against the war were still taking place. On the front pages of The Times on 1 and 2 August, there was an advertisement for the manifestation “War against War” under the "auspices of the International Labour and Socialist Bureau" at Trafalgar Square.[11] Harold Bing (1898-1975), a young conscientious objector to the First World War who was put in prison from 1916 to 1919, remembers this manifestation as follows:

As the succession of declarations of war escalated the crisis to a European conflict within a few days, pacifists were quickly silenced and the leading social democrats of all warring countries decided to support the war on the side of (or within) their governments.

The atmosphere in the streets shifted significantly towards the well-known “war enthusiasm,” or at least towards the mobilization of society as a whole for the war effort.[13] Everyday life was “refracted” through the lens of war, as Maureen Healy has brilliantly shown for the case of Vienna.[14] Shopping, cooking, child-rearing, reproduction, homework, leisure and neighbor relations were no longer considered private but became a matter of state, a matter of the war effort.

Re-Opening in Wartime↑

The beginning of the Great War in August 1914 took theatres by surprise in their planning of the fall season’s programme. Some directors used the special war clauses in their license and contracts to close down their theatres. After a relatively short moment of shock in the fall of 1914, most entertainment venues in European cities reopened their doors and were highly frequented throughout the war years. Their programmes and spectacles, however, changed significantly from those of the pre-war years.

In all combatant nations, both the government and intellectual establishment turned the First World War into an ideological and cultural war. In the war’s first months, a wide range of quickly written or adapted patriotic “war plays” in all popular genres from comedies, farces and melodramas to operettas and variety shows were staged on the home fronts as part of a spontaneous cultural mobilization. Both sides also welcomed a self-imposed “purification” boycott of all plays originating in “enemy states.” This led to far-reaching modifications in theatre repertories, especially in popular entertainment which had been oriented towards international successes before.

Representative repertory theatres such as the Comédie Française in Paris, Max Reinhardt’s (1873-1943) Deutsches Theater in Berlin and the Hofburgtheater in Vienna celebrated their re-openings in wartime with selected classical plays that could reinforce and ennoble the jingoistic and aggressive feelings of the day: Heinrich von Kleist’s (1777-1811) Prinz Friedrich von Homburg, Friedrich Schiller's (1759-1805) Wallenstein and, on the other side, Pierre Corneille’s (1606-1684) Horace. To make sure that the plays, which were certainly not intended for such a simplistic interpretation, were understood in the right manner, they were not staged alone but embedded within a dense patriotic framework consisting of the national anthem, soldiers’ songs, introductory speeches, topical interludes, etc.[15]

The programmes of entertainment theatres in London, Berlin, Vienna and Paris in the first wartime season were full of war-related topical plays in light theatrical genres. Such operettas, comedies, farces and revues made use of a type of humor characterised by aggressive laughter and jubilant self-assertion with the inclusion of some melodramatic or serious elements. These wartime plays contributed to a general cultural war mobilization and captured the audience’s wish to feel and reinforce a sense of national unity.

The state of war led to a highly complacent image of national power, a celebration of national identity and the exaltation of patriotic devotion and the willingness to make sacrifices. Sacrifice was demanded especially of women who were encouraged to support the war with all their might on the home front.[16] Prevalent on the stage on both sides of the front was also the cultivation of the victim image. This was much more credible and thus more successful in France than in Germany due to the German invasion of Belgium and northern France. While the main German argument for victimization was the country’s encirclement by enemy powers conspiring against Germany,[17] many manifestations of popular culture at the beginning of the war, with their rhetoric of offensive attack and invasion, contradicted the official “defense thesis” of the German army command.

One typical mode of this aggressive humor is strongly related to sexualised allusions, as in the “patriotic tableau vivant” Krümel vor Paris by Franz Cornelius (1878-?)[18] staged at the Berlin Residenz-Theater, from October 1914 on. Here, the French nanny Iza Guignard sings about offensive German men, obviously interested in conquering her as well as her country.

Daß man den Deutschen gar nicht wiederkennt;

Seine Kraft ist phänomenal,

Kolossal, kolossal, kolossal!

O dieser Deutsche hat ein Temp’rament,

Daß man den Deutschen gar nicht wiederkennt! -

Ja, sie singen vom Rhein, von Paris und vom Main,

Wo sie geh’n, wo sie steh’n, woll’n sie rein![19]The scenic superimposition of a women’s body on a country’s territory – some press reviews note that the actress made significant gestures to her body when she sang about the Rhine, Paris and the Main – is a recurrent technique in these wartime plays. Theatrical performance seemed to be especially receptive to the linking of military and sexual violence, affirming and trivializing it, or as in a series of French war plays of a more melodramatic tone, using the violated woman as a representation of the nation as a whole.[20]

A second important topic of war comedies and revues was the reinforcement of war alliances. The “brothers in arms,” Austria and Germany, were a recurrent theme in Vienna and Berlin. The titles of some of the new plays of the period accentuated this relationship, such as Komm, deutscher Bruder (“Come on, German brother”) or Germania und Austria. On the other side, French war plays often included the character of a smart, well-dressed, polite and civilised British gentleman or officer.

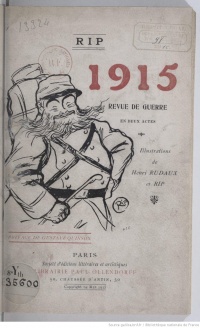

The purging of foreign influences, especially by boycotting enemy countries’ cultural imports, was itself made a subject on stage. Especially in topical revues, this theme was frequently referred to in a self-reflective, comical way, as is typical for this genre. In the Paris “revue de guerre” 1915 by Georges-Gabriel Thenon (1884-1941), who wrote under the pseudonym Rip, a renowned author of revues, one of the first scenes finds all foreign influences such as Berlin fashion, Viennese operetta and Richard Wagner’s (1813-1883) opera Parsifal as well as the tango and absinth waiting to be expelled from Paris, whereby Paris becomes a “real French city” again.[21]

Avec bonheur de tous ces gens

C’était bon avant que la guerre

Nous ait rendu moins indulgents :

Tous ces fantoches lamentables,

Nous les avons pris en horreur ;

Paris a compris son erreur,

Paris redevient raisonnable.

[...]

Paris sait redev’nir Paris,

Paris, la vraie ville française![22]A direct mirror-image, in the Berlin revue Woran wir denken (“What we are thinking of”), first performed on 26 December 1914 in the glamorous Metropol-Theater, one of the scenes takes place at a Berlin railway station where Paris fashion is escaping incognito and the “latest foreign dances” have their short entries as sumptuously costumed female figures. They are finally replaced by the wrongly forgotten Viennese waltz, personified by the popular Viennese music-hall and operetta actress Fritzi Massary (1882-1969).[23]

In addition to war alliances and external relations, another major theme on the stage was the national unity of the “people in arms” which went nearly undisputed and was capable of brushing away all political and social oppositions. It was often symbolised by the family but also by a stock of characters which allegedly covered all social classes.[24]

A constitutive part of the representation of a homogenised “united people” was the alignment of political opposition: those who were skeptical about the war were suddenly convinced, as in Rip’s revue 1915 where a waiter is teaching a patriotic lesson to a young dishwasher who does not understand why France has to fight a war.[25] The socialist hardliner developed a national conscience, as does the socialist worker Ferdinand Knietschke in the Berlin “patriotic revue” Der Kaiser rief... (“The Emperor called”) whose sudden change of mind when the war starts is one of the main topics of the play.[26] A cosmopolitan society woman might become a nurse to serve her country on the “home front” as in Berlin im Felde (“Berlin at the Front”),[27] among other scenarios.

The British all-volunteer army had to be significantly expanded at the beginning of the war without conscription. Therefore, many volunteers and young men were exposed to high levels of social pressure in order to convince them to enlist quickly in the British Expeditionary Force fighting in Belgium and Northern France. On the popular stage, this was reflected through an aggressive targeting of conscientious objectors or pacifists like Keir Hardie (1856-1915), former leader of the Labour Party in the UK and an eloquent activist for women's right to vote, self rule in India and the end of race segregation in South Africa. Hardie was one of the most consistent war opponents before and after the war began and was later stigmatised as a traitor. In the revue By Jingo if we do, debuted at London’s Empire Theatre on 19 October 1914, several offensive jokes or allusions are made at the expense of Hardie: “The Kaiser’s got pinched/And Keir Hardie's been lynched.”[28]

There were rare exceptions to these overtly jingoistic stage productions, such as E. Temple Thurston’s (1879-1933) comedy The Cost, which also premiered in October 1914 at the Vaudeville Theatre, a very similar venue to the Empire, both localised in London’s West End. In this play set in a typical upper-middle-class family, the imminence of war brings out everyone's negative characteristics – selfishness, chauvinism, etc. – except for the eldest son, John Woodhouse, a rising star in moral philosophy, who warns his family about the dangers of war:[29]

Finally, he enlists as well since even he cannot escape from “war hysteria.” He gets wounded at the front and can be healed superficially but he is told by doctors that he will never be able to think as he did before.

The critics reacted reservedly and found the play inopportune. A major criticism was that the play forced people to think about the same things they were already occupied with during the day.[31] The play was hastily withdrawn from the Vaudeville and did not reappear during the war.[32]

Traces of War in Escapist Entertainments↑

The public was looking for some laughs at the theatre as a diversion from the troubles of wartime reality and for imaginations of other, remote and better worlds. Nostalgic atmosphere and exotic settings increasingly replaced the patriotic verve of the early war plays.

In Vienna alone, more than twenty operettas had their first performance during the year 1915. Among these we find Auf Befehl der Kaiserin (“On orders of the Empress”, Theater an der Wien, 20 March 1915) by Bruno Granichstaedten (1879-1944) who called it “an operetta idyll from the old cozy times,”[33] setting it in explicit opposition to the current times which were not cozy at all. Leo Ascher’s (1880-1942) operetta Botschafterin Leni (“Ambassadress Leni”, Theater in der Josefstadt, 19 February 1915), set in the slightly decadent court society of the 18th century in Germany and in Italy with a simple “Wiener Mädel” protagonist who becomes an emancipated woman sent to the court in Florence; the slightly titillating Hungarian operetta by Jenö Huszka (1875-1960), Die Patronesse vom Nachtcafé, (“Night-Club Girl”, Theater in der Josefstadt, 15 May 1915); and the happy and harmless operetta Die Millionengretl (“Greta with the Millions”) by Franz Schönbaumsfeld (Raimund-Theater, 27 November 1915). Interestingly, all these operettas feature a woman in the title role, a typical phenomenon in war entertainments at the home front which was adapted to the public audience which consisted mainly of women and soldiers on leave. Another important function of the Viennese operetta, especially needed in the face of the crisis the Habsburg monarchy went through, was its – often condescending – emphasis on the reunion of the different nationalities and cultures of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Emmerich Kálmán’s (1882-1953) Csardasfürstin (“The Gypsy Princess”), a smashing success at the time and still one of the most performed operettas of the period, responded especially well to the needs of a wartime audience tired of topical war operettas. Kálmán’s specialties, a melodramatic tone as well as musical and thematic inspiration from Hungarian folk culture, merged here with nearly apocalyptic verses hidden in an exuberant vitality at the end of the operetta. Everyone is dancing even as the whole world is sinking.[34]

Jaj mamám, was liegt mir am lumpigen Geld!

Weißt du, wie lange noch der Globus sich dreht,

Ob es morgen nicht schon zu spät![35]In Paris, the allusions to war had a longer life on the stage but they became more and more integrated into operettas or detective and espionage stories. The Théâtre Apollo, for example, put on Henri Goublier’s (1888-1951) war related operetta La cocarde de Mimi Pinson (“The cockade of Mimi Pinson”). The first act, set in a textile manufacture in Paris, shows female workers who decide to produce cocardes, the blue-white-red national symbols, as “love gifts” for the soldiers at the front. Here, more than one year after the war began, the depiction of the soldier’s life had already gained in realism as compared to the idealistic and old-fashioned idea of warfare which abounded in the first months of war. The following song references this early idealism, calling it the “dreamed war”:

Où les Français, drapeau au vent,

S’élancaient tous dans la mêlée

En se battant très crânement,

Où les éclairs des baionnettes

Au soleil joyeux scintillaient,

Où les refrains de nos trompettes,

Avec ardeur nous entraînaient.

Au lieu de cela,

L’on se bat

Sous la terre,

Avec mystère;

On avance à pas lents

Se cachant,

Mais pourtant

Par instant

L’on se rencontre face à face

Avec l’ennemi détesté,

Et malgré son habileté,

A se cacher,

Se défiler,

On le chasse![36]Slowly the theatres in Paris returned to their specialties in the sphere of entertainment theatre, namely the elegant Boulevard comedies and popular farces. The author and actor Sacha Guitry (1885-1957) remained productive in the most diverse genres – from comedy to revue and film – throughout the war. His comedy La jalousie (“Jealousy”) had its first performance on 8 April 1915 in the Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens. The intimate play deals with a furiously jealous husband who comes home a half hour late. He has just invented an excuse when finds out that his wife is not yet at home.[37] In La jalousie, Guitry dissects jealousy as an elementary emotion which was certainly flourishing with the separation of couples due to wartime mobilization.

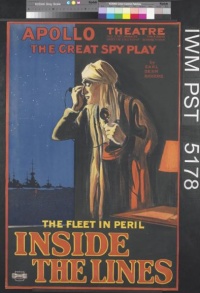

Throughout the year 1915, the London stages saw many escapist musical comedies such as Tonight’s the Night with music and lyrics by Paul Rubens (1875-1915) and a book adapted by Fred Thompson (1884-1949) from the French farce Les dominos roses (“Pink Dominoes”), written by Alfred Delacour (1817-1883) and Alfred Hennequin (1842-1887) in 1876. It premiered on Christmas Eve 1914 on New York's Broadway but with the production and cast of London's Gaiety Theatre. It then opened in London on 18 April 1915 and ran for a very successful 460 performances. Betty, with music from Paul Rubens and Ernst Steffan (1896-1967) and a book by Frederick Lonsdale (1881-1954) and Gladys Unger (1884-1940), certainly inspired by the fairy tale Cinderella, premiered in London on 24 April 1915 at the Daly’s Theatre after having been staged on Christmas Eve 1914 in Manchester. Betty had a run of 391 performances at the Daly’s and was staged again at New York’s Globe Theatre from October 1916 on. The “musical farcical comedy” The Only Girl with music by Victor Herbert (1859-1924), one of the most important American operetta composers, and a book by Henry Blossom (1866-1919) opened at London’s Apollo Theatre on 25 September 1915. It had premiered on Broadway on 2 November 1914 and ran successfully there until June 1915. The libretto of The Only Girl has an interesting transnational genealogy: it was based on the American play Our wives (1912) by Frank Mandel (1884-1958) and Helen Kraft which itself was an adaptation of German playwright Ludwig Fulda's (1862-1939) Jugendfreunde (1898).

All three productions were created after the World War had begun but were not originally opened in London and had already had success elsewhere. The plots of these three musical comedies were also similarly structured: they all tell the story of one or more high-born but irresponsible young men, reluctant to settle down and abide by their wife or girlfriend. They are gently forced into a legitimate relationship and finally admit their love to their “only girl.” In my view, this is a comedy plot appropriate to wartime which strangely echoes, through inversion, the adultery farces of the pre-war years. The girls, for their part, are uncommonly active in gaining (or testing) their partner's commitment. The musical scores “contained several appealing ballads”[38] and advanced slightly into more modern musical terrains, especially the Afro-American rhythms of ragtime and Latin-American dances. Although the British musical comedies Tonight’s the Night and Betty were the more successful with London’s wartime audiences, its American counterpart, Victor Herbert’s The Only Girl was far more influential. “The show was a sensation for its very simplicity.”[39] It was a musical comedy that dispensed with a chorus and overture and relied on humorous dialogue, the self-referentiality of the play and the power of the female protagonist, a composer of musical comedies. “[A]ll the numbers leaped up out of the plot continuity without a single diversion.”[40] Besides the militaristic song “Here's to the land we love, Boys,” The Only Girl had one hit that endured long after the musical itself had quit the stage: the romantic song “When You're Away” in a waltz tune which appealed to soldiers and young women separated from their beloved.[41]

Besides the romantic and nostalgic fare, there were scores of productions that escaped wartime reality by inviting the audience into exotic scenery and settings. This was the case for one of the longest running productions of London's West-End, the orientalist, pantomime-like musical comedy Chu Chin Chow, written, produced and directed by Oscar Asche (1871-1936) at His Majesty's Theatre which he had managed since 1907. It premiered on 3 August 1916 – at a time when the murderous battles of Verdun and the Somme were being fought – and remained on stage for the spectacular number of 2,238 performances until 22 July 1921, the moment when Adolf Hitler (1889-1945) became the leader of the National Socialist German Workers Party. The story of Chu Chin Chow is based on the tale of Ali Baba and the forty thieves. “The immediate popularity of Chu Chin Chow rested firmly on its fanciful visual elements – the sets, costumes and stage effects.”[42] It was a big budget production with sumptuous stage sets and exotic costumes, big dance routines and a large cast including animals like a camel, a snake and a donkey. Whereas the visual elements all aimed at conveying a most exotic scenery, the musical score of Chu Chin Chow remained firmly rooted in mainstream English popular music of the time.[43] The first scene, set in the palace of Kasim Baba, the wealthy brother of Ali Baba who awaits the visit of the Chinese merchant Chu Chin Chow and is preparing a feast, began with the following song:

And conger eels cooled in snow,

Here be shell-fish stuffed with spices

And fricasseed sturgeon-roll

[...][44]This was certainly a good start for dreams of oriental abundance and luxury in a wartime society affected by food scarcity and renouncement.

Among Vienna's operettas, another big wartime success was Leo Fall’s (1872-1925) Die Rose von Stambul (“The Rose of Stambul”) which opened on 2 December 1916 at the Theater an der Wien. The story is set in contemporary Turkey (the Ottoman Empire), the current ally of Germany and Austria-Hungary. Within an amply gilded Turkish-oriental setting, Achmed Bey, the son of an Ottoman minister, is to marry the Pasha's daughter, Kondja Gül. According to tradition, they are not allowed to see each other before the wedding, and, at their first meeting, a folding screen stands between them on stage. However, Kondja Gül has fallen in love with the author of modern novels, André Léry, without knowing him. It is revealed that André Léry was just a pen name adopted by Achmed Bey himself in order to publish such progressive literature. Still, an additional three acts were needed for the revelation to reach Kondja Gül – three acts in which the praise of a modernizing Turkey is unmistakable.[45]

Warfare Spectacles↑

In the later years of the war, along with general penury, theatres were in a difficult situation. Supply problems in the cities were increasing and the heating and lighting of theatres posed a challenge. The difficulties of everyday life which also affected the wealthier citizens reduced traditional audience size. In turn, new segments of the population, especially the soldiers on leave but also refugees, working women and children sought entertainment in the theatres. Regulations (especially concerning closing hours), a lack of public transport in the evening and censorship further restricted the possibilities open to theatres. A look in the newspapers reveals, however, that nearly all theatres and entertainment venues stayed open. Official closings of theatres in some cities, due to lack of coal for example, led to protests from public and producers alike and could not be sustained.[46]

One consequence of the experience of technical warfare and the “crisis of representation” as Bernd Hüppauf called it[47] within entertainment theatre was the great success and establishment of non-narrative, spectacular and fragmented types of performances such as circuses, big revues, cabaret and variety shows with a combination of cinema, music, artistic acts and theatre sketches. Even though all these genres existed before 1914, they began to attract a socially diversified mass public eager for sensational entertainment. They provided a model for institutions of high culture like the Paris Opera: during wartime the Opéra de Paris often did not perform entire operas but “opera medleys” which were a succession of three or four acts of different operas, compiling the most popular arias without the need for a whole opera cast.

The revue was seen – critics all over Europe agreed on this point – as the theatre form of the moment. In the London theatre weekly The Era, in December 1915, revue was called the “staple attraction” of the music halls. This pointed to the phenomenon that the “Single Turn” - music hall was being increasingly replaced by a structure where a few single acts served as introduction to one main attraction with a big cast and décor.[48] Adolphe Brisson (1860-1925), critic for the newspaper Le Temps, starts his review of Rip’s newest revue in October 1915 with the following statement: “Sans doute aurons-nous, cet hiver, beaucoup de revues. C’est un genre de spectacle qui agrée aux dispositions présentes du public. On écoute une revue, comme on lit un journal, avec l’obsession de l’actualité [...].”[49] Rip's revue 1915 and the sequel La revue nouvelle 1915 demonstrate this fact with self-confident irony. In the first scene, condolences are offered to all other theatrical genres, because: “on ne joue plus que des revues.”[50]

In its specific flexibility and vitality, the revue was able to combine topical and escapist elements. Its characteristic self-reflexivity integrated all possible criticism from the outset. The strict separation between stage and auditorium was suspended by using gang planks through the auditorium or by simply letting dancers or actors enter the auditorium and use it as a stage. Especially the chorus girls – fearfully watched by the censors – had to bridge the gap between anonymizing modernity and erotic intimacy.

Concerning more classical narrations, most successful plays offered war related variations of genres that had become popular in the years before the war: detective or espionage plays, adventure spectacles and extravaganzas. The Théâtre du Châtelet in Paris for example, known for its sophisticated technical stage sets, showed the spectacular play Les Exploits d’une petite Française (“The Achievements of a French Girl”) from December 1915 on. The public was able to see a real war of military inventions. In the theatre magazine Les deux masques, the initial dramatic conflict is described:

This leads to a wild chase which takes all characters involved from one end of the world to the other: from China to Alsace, the story progresses with incredible speed. In a remarkable show-down, the young French girl Mariette succeeds in tracking down the German colonel Von Blitz who is in possession of the formula to produce an explosive and is starting to make it in a factory in Mulhouse. By a trick of Marietta, the formula finally gets trapped in an iron flask and the whole factory is blown up together with Von Blitz. The critics pointed out “the cinematographic style” of this and other plays of this type because of the rapidity of the action and the absence of more elaborate characters or emotions, but also because of the vivid and original performances of the actors.

The circus, with traditional affinities to war and the military,[52] must be included in a study of war-time entertainments. For example, the successful Dresden-based circus manager Hans Stosch-Sarrasani (1873-1934) led a circus company with more than 500 employees in 1914.[53] Sarrasani’s formula for success before the war had been a combination of traditional circus attractions, such as horse and wild animal’s dressage, magicians, clowns, acrobats, etc. with the spectacular use of new technologies in the arena – cars, planes and film projections became integral parts of his shows.[54] At the outset of the war, Sarrasani, as many others in the entertainment business, was affected by the collapse of the international circuits of artists and entertainers. Many of his foreign employees had to leave Germany in a rush. Sarrasani adapted his shows entirely to the topic of the war. In Dresden, he staged his “arena war play” Europa in Flammen which literally presented battles with all types of new weapons and a strongly propagandistic storyline – all to great success. However, in Berlin, he had some problems convincing the military command that his spectacles were an important contribution to the German war effort. The Berlin censors refused to authorise Europa in Flammen because of its sensational depiction of the current war which might agitate and perturb spectators. Only in 1917, with the strengthening of German Inlandspropaganda (domestic propaganda), were new possibilities opened to Sarrasani. From June to September 1918, nearly until the bitter end of the war, he was allowed to perform his ever more monumental show Torpedo – los! in Berlin’s Zirkus Busch, staging submarine warfare, the explosion of a shipyard, a navy ballet as well as the bombing of London with zeppelins.[55]

On the literary stages, the prevailing tone had significantly shifted towards a darker, more disillusioned view of the times. The protagonists on stage were no longer heroes and they could not – as in the spectacular plays – be replaced by weapons and machines. Max Reinhardt's seminal production of Georg Büchner's (1813-1837) Dantons Tod opened at Berlin's Deutsches Theater in December 1916 and is a remarkable example of this tendency: his Danton is a cynical and skeptical “hero” of the French Revolution in sharp contrast to the hysterical masses unleashed on stage.

Eccentric and unconventional women were increasingly made protagonists in modern as well as classical dramas. At the venerable Comédie Française in Paris, Victor Hugo’s (1802-1885) rarely performed play Lucrèce Borgia (1833), set in the luxurious but murderous atmosphere of early 16th century Italy that shows – in Hugo's own words – moral deformation leading to vice and crime as embodied by a beautiful woman and mother,[56] had its premiere on 27 February 1918. It thus entered the repertory of the Théâtre Français with a famous cast including Eugénie Segond-Weber (1867-1945) as Lucrèce Borgia and M. Albert Lambert (1864-1941) as Gennaro. The play begins with the following sentence, part of a conversation between young Italian lords at a carnival party in Venice:

For Victor Hugo, the epoch of 'so many horrible actions' that the opening sentence refers to, could certainly relate to recent events of the July Revolution (1830) in France. And this reference to the present probably worked again for the public at the Comédie Française watching the play in February 1918, in the fifth year of the war.

By 1918, the heroes of 1914 – determined and happy soldiers with their waving flags – had left the stage both in the popular and the literary theatres. What followed was rather unsettling: the spectacular weapon overkill in the patriotic war plays as well as the ambivalent protagonists of modern and classical drama staged in 1918, the sequenced logic of revue replacing traditional narrative forms and the escapist exoticism of musical theatre.

Conclusion↑

The lively and diversified theatrical culture in all big European cities was profoundly transformed by the onset of the First World War. During the first wartime season, topical and patriotic plays dominated theatre programmes, mostly integrated into the popular genres of the day, the operetta, revue, comedy and music-hall show. These often made use of an aggressive form of humor.

After the illusion that the war could be rapidly won slowly vanished, escapist entertainments such as operettas with remote settings, nostalgic farces and outdated comedies showing the “good old times” increasingly replaced topical plays. Nevertheless, a deeper analysis of these wartime productions which were supposed to keep the war at bay for the duration of the performance, shows implicit traces of war such as a carpe diem-mentality given a completely unpredictable future. The gap between the reality of technical warfare and the cozy world of make-believe on stage was often noticed by critics and the public. It was also this gap that made the theatre so attractive for new audiences such as working women as well as soldiers on leave and war refugees.

Although living conditions deteriorated across Europe in the late war years, especially in the big metropolises of the Central Powers, Berlin and Vienna,[58] but also in Southern and Eastern Europe, theatres remained active and successful throughout the last months of the war. Whether the public found humorous relief, pessimist reflection, patriotic perseverance or "senseless" diversion depended very much on the particular venue. It certainly found in theatre-going a certain sense of normality, a way to gather and to warm up again in winter.

To return to New York's Broadway, at the Playhouse Theater, on 11 November 1918, the day Germany signed the armistice with the Allies at Compiègne, the day the fighting on the Western front finally stopped, one could go to see the premiere of a show prophetically named Home Again, based on the folk poems and stories of the highly popular American poet James Whitcomb Riley (1849-1916).[59]

Eva Krivanec, Humboldt Universität zu Berlin

Section Editors: David Welch; Dominik Geppert

Notes

- ↑ "A Third Party is boisterous fun, in: New York Times, 4 August 1914, p. 11.

- ↑ In many slightly smaller European cities, we can find similar developments of theatre production during the war years and successful plays staged in the big metropolis were often soon shown throughout the country (as happened with the patriotic war revue "Immer feste druff" which was created at Berlin's Theater am Nollendorfplatz on 1 October 1914). Some new developments (for example German expressionist theatre) emerged beyond the capitals, supported by innovative theatre directors and facilitated by a slightly more liberal censorship.

- ↑ For further information on theatres at the front in the First World War, see: Collins, L.J.: Theatre at War, 1914-1918, Basingstoke 1997; Baumeister, Martin: Kriegstheater. Großstadt, Front und Massenkultur, Essen 2005; Merveilleux du Vignaux, Anne: Théâtre et cinéma aux armées. Armistices d'un soir, Ivry 2010.

- ↑ See Charle, Christophe: Théâtres en capitales: Naissance de la société du spectacle à Paris, Berlin, Londres et Vienne, Paris 2008, pp. 23-53.

- ↑ See Maase, Kaspar: Grenzenloses Vergnügen. Der Aufstieg der Massenkultur 1850-1970, Frankfurt 2001.

- ↑ See Fritzsche, Peter: Reading Berlin 1900, Cambridge, MA 1996, p. 6.

- ↑ See The Times (London), 1 August 1914, p. 1.

- ↑ See Le Petit Journal (Paris), 31 July 1914, p. 4, http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k620528z/f4.image.r=Le%20Petit%20journal%20Paris.langDE (retrieved: 17 November 2014).

- ↑ See Dubé, Paul / Marchioro, Jacques: L'Alcazar d'Été et les Ambassadeurs. Issued by: Du temps des cerises aux feuilles mortes. Un site consacré à la Chanson Française de la fin du Second Empire à la fin de la Seconde Grande Guerre, http://www.dutempsdescerisesauxfeuillesmortes.net/textes_divers/cafes_concerts_et_music_halls/alcazar_d_ete_et_ambassadeurs.htm (retrieved: 11 December 2013).

- ↑ See Fremden-Blatt (Vienna), 25 July 1914, p. 9, http://anno.onb.ac.at/cgi-content/anno?aid=fdb&datum=19140725&seite=9&zoom=33 (retrieved: 17 November 2014).

- ↑ See The Times (London), 1 August 1914, p. 1.

- ↑ Harold Bing, Interview of 1974, Ref. Nr. 358, Sound Archive, Imperial War Museum, http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80000357 (retrieved: 17 November 2014), as cited in: Smith, Lyn (ed.): Voices against War. A Century of Protest, Edinburgh 2009, p. 25.

- ↑ See for example Verhey, Jeffrey: The Spirit of 1914: Militarism, Myth and Mobilization in Germany, Cambridge et al. 2000; Pennell, Catriona: A Kingdom United: Popular responses to the outbreak of the First World War in Britain and Ireland, Oxford 2012; Purseigle, Pierre: Mobilisation, sacrifice et citoyenneté. Angleterre-France, 1900-1918, Paris 2013.

- ↑ See Healy, Maureen: Vienna and the Fall of the Habsburg Empire. Total War and Everyday Life in World War I, Cambridge et al. 2004.

- ↑ For a more detailed account of these stage productions see Krivanec, Eva: Kriegsbühnen. Theater im Ersten Weltkrieg. Berlin, Lissabon, Paris, Wien, Bielefeld 2012, pp. 94-102.

- ↑ E.g. in the war-operetta Gold gab ich für Eisen! by Emmerich Kálman (Theater an der Wien, premier: 17 October 1914), where all women support the war-aid-campaign “Gold gab ich für Eisen!” – I gave gold for iron – with patriotic verve.

- ↑ See Rürup, Reinhard: Der "Geist von 1914" in Deutschland: Kriegsbegeisterung und Ideologisierung des Krieges im Ersten Weltkrieg, in: Hüppauf, Bernd (ed.): Ansichten vom Krieg: Vergleichende Studien zum Ersten Weltkrieg in Literatur und Gesellschaft, Königstein 1984, pp. 1-30. Germany had to fight against “English professional jealousy” and “French revanchism” and was caught in an “existential struggle” against “encirclement” by enemies.

- ↑ Franz Cornelius was probably the pseudonym of Siegfrid Zickel.

- ↑ “O the German has a temperament / That one doesn’t recognise him anymore / His power is phenomenal / gigantic, gigantic, gigantic / O the German has a temperament / That one doesn’t recognise him anymore / Yes, they sing about the Rhine, about Paris and the Main, / Where they go, where they stand, in they go!” [translation: author] in Franz Cornelius’ Krümel vor Paris! Ein vaterländisches Zeitbild. Genehmigt mit den handschriftlichen Streichungen und Änderungen für das Residenz-Theater, 6 December 1915 [Censorship’s manuscript] Landesarchiv Berlin, A.Pr.Br. 030-05-02, Nr. 6026, pp.12-13.

- ↑ See Baumeister, Martin: Kriegstheater. Großstadt, Front und Massenkultur, Essen 2005, pp. 89-92.

- ↑ See Rip, 1915. Revue de Guerre en deux actes, Préface de Gustave Quinson, Dessins de Henri Rudaux et Rip, Paris 1915, pp. 1-7 (Théâtre du Palais Royal, Paris, premier: 24 April 1915).

- ↑ “Believe me, Paris is getting rid / With pleasure of all these people / It was alright before the war / made us less indulgent: / All these pathetic puppets / we are now loathing them; / Paris has understood its mistake, / Paris is getting reasonable again. / [...] / Paris can become Paris again / Paris, the real French city!“ [translation: author], Rip: 1915. Revue de Guerre, p.7.

- ↑ See Franz Arnold, Leo Leipziger, Walter Turszinsky: Woran wir denken! Bilder aus großer Zeit. Musik von Max Winterfeld (Jean Gilbert). Genehmigt für das Metropol-Theatre, 8 January 1915 [censorship’s manuscript], Landesarchiv Berlin, A.Pr.Br. 030-05-02, Nr. 6126.

- ↑ See Baumeister, Kriegstheater 2005, pp.70-76; Verhey, The Spirit of 1914 2000, pp. 1-12.

- ↑ See Rip, 1915. Revue de Guerre, pp. 32f.

- ↑ See Franz Cornelius: Der Kaiser rief... Ein vaterländisches Genrebild aus unseren Tagen. Genehmigt für das Residenz-Theatre, 29 August 1914 [censorship’s manuscript], Landesarchiv Berlin, A.Pr.Br. 030-05-02, Nr. 6025. (Scene 9).

- ↑ See Pordes-Milo, Hermann Frey: Berlin im Felde. Vaterländisches Zeitbild mit Musik von Fritz Redl. Genehmigt für das Walhalla-Theatre, 03-10-1914 [censorship’s manuscript], Landesarchiv Berlin, A.Pr.Br. 030-05-02, Nr. 6047.

- ↑ See Williams, Gordon: British Theatre in the Great War. A Revaluation, London et al. 2003, p. 33.

- ↑ See Kosok, Heinz: The Theatre of War. The First World War in British and Irish Drama, Basingstoke 2007, p. 15.

- ↑ Thurston, E. Temple: The Cost. A Comedy in Four Acts, London 1914, p. 33.

- ↑ See Mr. Thurston's New Play: "The Cost" at the Vaudeville, in: The Times (London), 14 October 1914, p. 11.

- ↑ See Williams, British Theatre in the Great War 2003, p. 180.

- ↑ See Granichstaedten, Bruno: Auf Befehl der Kaiserin! Ein Operetten-Idyll aus alten gemütlichen Zeiten in drei Akten von Leopold Jacobsohn und Robert Bodanzky. Klavierauszug, Vienna 1915.

- ↑ See Frey, Stefan: “Unter Tränen lachen.” Emmerich Kálmán. Eine Operettenbiographie, Berlin 2003, pp. 108-112.

- ↑ “Jaj mamám, dear brother, I’m buying the world! / Jaj mamám, what else should I do with the lousy money! / Do you know how long this globe will be turning? If tomorrow is not too late!” [translation: author]. Stein, Leo / Jenbach, Bela: Die Csárdásfürstin. Operette in drei Akten, Musik von Emmerich Kálmán. Textbuch der Gesänge, Vienna et al. 1916, p. 33.

- ↑ “Instead of the dreamed war, / Where the French, with their flags in the wind, / Threw themselves into the fray / Fighting obstinately, / Where the blades of the bayonets / Scintillated in the happy sun, / Where the chorus of our trumpets, / With swing carried us along. // Instead of this, / One fights / Underground / with mystery; // One advances with slow steps / Hiding oneself, / But still / now and then // One encounters face to face / The detested enemy, / And in spite of his cunning, / To hide himself, / To skive off, / One chases him!” [translation: author]. Ordonneau, Maurice / Gally, Francis: La Cocarde de Mimi Pinson. Opérette en trois actes, Musique de Henri Goublier fils, Paris 1915, p. 31.

- ↑ See Guitry, Sacha: La jalousie. In: La Petite Illustration. Théâtre, 28 July 1934.

- ↑ Larkin, Colin: Betty, in: Larkin, Colin (ed.): The Encyclopedia of Stage and Film Musicals. London 1999, p. 64.

- ↑ Mordden, Ethan: Anything Goes. A History of American Musical Theatre, Oxford et al. 2013, p. 140.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 141.

- ↑ See Gould, Neil: Victor Herbert. A theatrical life, New York 2008, p. 477; see also Bordman, Gerald / Norton, Richard: American Musical Theatre. A Chronicle. 4th edition, Oxford et al. 2011, pp. 349-350.

- ↑ Everett, William A.: Chu Chin Chow and Orientalist Musical Theatre in Britain during the First World War, in: Clayton, Martin / Zon, Bennett (eds.): Music and Orientalism in the British Empire, 1780's-1940's. Portrayal of the East, Farnham 2007, pp. 277-296, here p. 277.

- ↑ See Ibid.

- ↑ Asche, Oscar (words) / Norton, Frederic (music): Chu Chin Chow. A Musical Tale of the East. Vocal Score, London 1916, pp. 4-5. (available at archive.org: https://archive.org/details/chuchinchowmusic00nort, retrieved: 19 February 2014).

- ↑ See Brammer, Julius / Grünwald, Alfred / Fall, Leo (music): Die Rose von Stambul. Operette in drei Akten, Vienna 1916 [Prompt Book, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Musiksammlung, 299429-B.Mus], http://digital.bib-bvb.de/view/bvbmets/viewer.0.5.jsp?folder_id=0&dvs=1416230073419~542&pid=6213951&locale=en_US&usePid1=true&usePid2=true (retrieved: 17 November 2014).

- ↑ See Schlesinger, Ernst: Kohlenmangel und Theaterschließung, in: Die Schaubühne, 22 February 1917, pp. 183-85, http://quod.lib.umich.edu/g/genpub/acd6054.0013.001/197?view=image&size=100 (retrieved: 17 November 2014).

- ↑ See Hüppauf, Bernd: Experiences of Modern Warfare and the Crisis of Representation, in: New German Critique, 59 (1993), pp. 41-76.

- ↑ See Williams, British Theatre in the Great War 2003, pp. 94-95.

- ↑ “Probably we will have a lot of revues this winter. It is the type of spectacle that suits the current disposition of the public. One listens to a revue like one reads a newspaper, with the obsession of topicality” [translation: author]. Brisson, Adolphe: Théâtre Antoine. La nouvelle Revue 1915, in: Le Temps, 18 October 1915, p. 3, http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k242330v/f3.image.langDE (retrieved: 17 November 2014).

- ↑ “They stage nothing but revues” [translation: author]. Saix, Guillot de: Les Premières. La nouvelle Revue 1915, in: L’Eclair, 18 October 1915, p. 4.

- ↑ “An old French engineer, emigrated to Australia, has invented a new explosive which would ensure us a quick and definitive victory; the German colonel von Blitz has got the order to misappropriate the invention at any cost” [translation: author]. Le Semainier: La Semaine – Châtelet, in: Les deux Masques, 19 December 1915, p. 72.

- ↑ The history of modern circus is closely related to the conditioning of horses and military riding schools. Around 1750 in England, trick horse-riding was emancipated from its noble and military origins and was shown as public entertainment in special amphitheatres.

- ↑ See Günther, Ernst / Winkler, Dietmar: Zirkusgeschichte. Ein Abriß der Geschichte des Deutschen Zirkus, Berlin 1986, p. 121.

- ↑ See Otte, Marline: Sarrasani’s Theatre of the World. Monumental Circus Entertainment in Dresden, from Kaiserreich to Third Reich, in: German History 17/4 (1999), pp. 527-542.

- ↑ See Baumeister, Kriegstheater 2005, pp. 187-191.

- ↑ Lucrèce Borgia, for Hugo, was not simply a cruel and terrifying poisoner and femme fatale but a tragic figure and loving mother as well as an interesting and intriguing female character.

- ↑ “We live in an epoch where the people commit so many horrible actions that no one talks about this one anymore, but there certainly hasn't been any more sinister and mysterious event than this one.” [translation: author] The lords then relate the most sanguinary and incestuous stories about the Borgia family. Hugo, Victor: Lucrèce Borgia. Drame. Deuxième Edition, Paris 1833, p. 5-6, http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k72005m.r=.langFR (retrieved: 17 November 2014).

- ↑ See Pfoser, Alfred/Weigl, Andreas (eds.): Im Epizentrum des Zusammenbruchs. Wien im Ersten Weltkrieg, Vienna 2013.

- ↑ See the entry for “Home Again” at the Internet Broadway Database: http://ibdb.com/production.php?id=6967 (retrieved 3 March 2014).

Selected Bibliography

- Baumeister, Martin: Kriegstheater. Grossstadt, Front und Massenkultur 1914-1918, Essen 2005: Klartext.

- Charle, Christophe: Théâtres en capitales. Naissance de la société du spectacle à Paris, Berlin, Londres et Vienne, 1860-1914, Paris 2008: Albin Michel.

- Collins, L. J.: Theatre at war, 1914-1918, Oldham 2003: Jade.

- Everett, William A.: Chu Chin Chow and orientalist musical theatre in Britain during the First World War, in: Clayton, Martin / Zon, Bennett (eds.): Music and orientalism in the British Empire, 1780s to 1940s. Portrayal of the East, Aldershot; Burlington 2007: Ashgate, pp. 277-296.

- Frey, Stefan: 'Unter Tränen lachen'. Emmerich Kálmán. Eine Operettenbiographie, Berlin 2003: Henschel.

- Fritzsche, Peter: Reading Berlin 1900, Cambridge 1998: Harvard University Press.

- Healy, Maureen: Vienna and the fall of the Habsburg Empire. Total war and everyday life in World War I, Cambridge 2004: Cambridge University Press.

- Hüppauf, Bernd: Experiences of modern warfare and the crisis of representation, in: New German Critique 59, 1993, pp. 41-76, doi:10.2307/488223.

- Kosok, Heinz: The theatre of war. The First World War in British and Irish drama, Basingstoke 2007: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Krivanec, Eva: Kriegsbühnen. Theater im Ersten Weltkrieg. Berlin, Lissabon, Paris und Wien, Bielefeld 2012: Transcript.

- Maase, Kaspar: Grenzenloses Vergnügen. Der Aufstieg der Massenkultur 1850-1970, Frankfurt a. M. 1997: Fischer Taschenbuch.

- Merveilleux du Vignaux, Anne: Théâtre et cinéma aux armées armistices d'un soir, Ivry-sur-Seine 2010: Ecpad.

- Mordden, Ethan: Anything goes. A history of American musical theatre, 2013.

- Otte, Marline: Sarrasani's theatre of the world. Monumental circus entertainment in Dresden, from Kaiserreich to Third Reich, in: German History 17/4, 1999, pp. 527-542, doi:10.1093/026635599669435101.

- Pfoser, Alfred / Weigl, Andreas (eds.): Im Epizentrum des Zusammenbruchs. Wien im Ersten Weltkrieg, Vienna 2013: Metroverlag.

- Rürup, Reinhard: Der 'Geist von 1914' in Deutschland. Kriegsbegeisterung und Ideologisierung des Krieges im Ersten Weltkrieg, in: Hüppauf, Bernd-Rüdiger (ed.): Ansichten vom Krieg. Vergleichende Studien zum Ersten Weltkrieg in Literatur und Gesellschaft, Königstein 1984: Forum Academicum, pp. 1-30.

- Smith, Lyn (ed.): Voices against war. A century of protest, Edinburgh 2009: Mainstream.

- Verhey, Jeffrey: The spirit of 1914. Militarism, myth and mobilization in Germany, Cambridge; New York 2006: Cambridge University Press.

- Williams, Gordon: British theatre in the Great War. A revaluation, London 2005: Continuum.