Beginning of the Occupation↑

Luxembourg's occupation had been planned for years. The German army and navy's 1891 yearbook explained the strategic position of Luxembourg. The violation of its neutrality was foreseen, in spite of Luxembourg’s membership in the Zollverein. The only protection that the small, neutral, demilitarized country enjoyed was international law. From the onset, Britain explained that it refused to go to war for Luxembourg unless all the signatories of the Treaty of London (1867) would intervene together. Since two of these signatories were Germany and France, Luxembourg’s neutrality defense clause was, in essence, worthless.

On 1 August 1914, after days of international crisis, the first violation of the neutrality occurred. After German soldiers entered Luxembourg in Troisvierges, Prime Minister Paul Eyschen (1841-1915) did not order the planned destruction of bridges and tunnels linking Luxembourg with Germany. Eyschen was aware of the grave danger. On 2 August, at 3 pm, Germany invaded the Grand-Duchy. Due to a lack of manpower and modern equipment, the Luxembourg Company of Volunteers, which was 120 men strong and the only military force, did not fire a single round at the Germans who would allow the company and police forces to remain in existence as order-keeping forces.

Reasons for Germany’s Occupation↑

The Germans needed to maintain Luxembourg’s occupation for three strategic reasons:

- to guarantee the security of the Diedenhofen fortress (Thionville in French)

- to use their position in southern Luxembourg for the artillery shelling of French Lorraine

- to use the railroads leading to Belgium and France

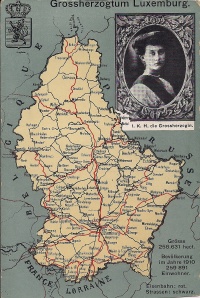

The invading troops seized all means of communication and transportation and censored the press, effectively isolating the country from the rest of the world. The government and Marie-Adélaïde, Grand-Duchess of Luxembourg (1894-1924) immediately protested against the occupation. It put the Grand-Duchy in a bizarre situation: the Germans accepted Luxembourg’s official neutrality, as they did not consider the country as an enemy and therefore did not formally declare war. It gave the government the opportunity to regain some control. As long as the cabinet did not interfere with their direct interests, the Germans allowed it to rule the country. Wilhelm II, German Emperor (1859-1941) installed his headquarters in the capital from 30 August until 28 September 1914. At the request of the local authorities a German “Military Center” was established in January 1915 to receive complains, under Colonel Richard Karl von Tessmar (1853-1928) who was also in command of the German garrisons.

Impact of the Occupation↑

The politics of non-resistance to the occupier yielded results: Luxembourg took an active role in its own occupation and thereby managed to circumvent the horrors of war, sparing its population from untold suffering. However, even if the survival of the nation was assured, political struggles and infighting would continue even during wartime. After the death of Prime Minister Eyschen, the Grand-Duchess tried to wrest back all the powers of the state. The resultant political instability led to several short-lived administrations.

The occupation’s main impact was economic. The steel industry was practically inactive until October 1914 since the German army was using the railroad lines for strategic reasons. This in turn had direct consequences on mining activities, though other sectors were also disrupted. Hundreds of foreign migrant workers left, diminishing the productive capacity of the country. Under the first two years of the German occupation, various industries increased their production, yielding results comparable to pre-occupation, reaching a peak in 1916. However, for other industries, results declined. Nevertheless production never halted in the factories.

In everyday life, the Germans were quartered in private houses, barns, and schools. The interaction between soldiers and the civilians was cordial, despite the occupation. Some citizens pitied their poor living conditions, summer heat and fatigue the German soldiers were exposed to. At first, the soldiers took their food from local resources, though the German army eventually supplied their troops, making requisitions unnecessary. Nonetheless, during the entire war, soldiers secretly bought food from peasants. In doing so, the big farmers were eager to make easy profits, yet their actions led to famine among their countrymen. In addition to food shortages, the Luxembourger’s main concerns included air bombings targeting the steel industry, railroad lines, and stations, and the German secret police arresting hundreds of people suspected of spying activities or pro-Allies feelings. The Germans installed anti-aircraft batteries in the south to protect the steel industry. Afterwards, due to the intensification of bombing against the capital city, they also installed some guns there to protect the local steel industry, which produced vital grenades and shells for the Reich. In 1917, workers went on strike, as their pay was no longer sufficient to provide food for their families.

End of the War and the Occupation↑

In 1918, the Germans lost the war and the occupation came to an end, also ending the bitter struggle between the Grand-Duchess and the political parties. Marie-Adélaïde’s abdication was based on her perceived pro-German tendencies, her vehement opposition to certain crucial reforms such as electoral reforms, and her attempt to wrest back power, which put into question her legitimacy as a ruler. French and Belgian political feuding put additional pressure on her to abdicate.

Richard Seiwerath, University of Liège

Section Editor: Emmanuel Debruyne

Selected Bibliography

- Faber, Ernest: Luxemburg im Kriege, 1914-1918, Mersch 1933: Fr. Faber.

- Robert, Jean-Pierre: Die Fliegerangriffe auf Luxemburg während der Weltkrieges 1914-1918 in historisch-chronologischer Darstellung, Luxembourg 1922: Th. Schroell.

- Trausch, Gilbert: La stratégie du faible. Le Luxembourg pendant la Première Guerre mondiale (1914-1919): Le rôle et la place des petits pays en Europe au XXe siecle (Small countries in Europe, their role and place in the XXth century), Baden-Baden; Brussels 2005: Nomos; Bruylant, pp. 45-176.