Family Background and Early Career↑

A Protestant peasant from Poitiers, Jacques Nivelle, Robert Nivelle’s (1856-1924) grandfather, fought in Napoleon’s army. Marie Nivelle, Robert Nivelle’s father, made nearly his whole career in the infantry regiment where he was eventually promoted to major. His wife Theodora Sparrow, born in England, came from a family of Protestant clergymen.

After outstanding studies in Saint Omer and Rouen, Robert Nivelle studied at the Polytechnique then at the military Academy of Artillery and the War Academy. He ranked thirteenth out of seventy-two with an “A” grade. It was then noticed that he could speak German well and English fluently. “He is very distinguished, with exceptional intelligence, charming, perfect manners,” commented his teachers.[1] However, the beginning of his career was nothing exceptional and his position regarding the Dreyfus affair impeded his advancement.

World War One↑

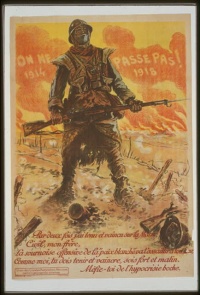

In 1914 Nivelle became an officer who distinguished himself for his talents as an organizer. His progression during the war was fast: he was colonel of the 5th Artilleries in 1914, brigadier in December, major general in May 1915 and lieutenant-general in February 1916. In command of the Second Army at Verdun, he was tasked with containing and, if possible, forcing the Germans to retreat. He achieved this aim at the end of 1916 which gained him immense prestige.

In a context of chronic political instability he was appointed commander-in-chief mainly for political reasons. The 1917 spring offensive, desired by the French government and prepared by Joseph Joffre (1852-1931), was finalized by Nivelle.

Conflict with Paul Painlevé (1863-1933), the war minister, intrigues among the generals and Nivelle’s lack of authority combined with the ambiguous attitude of the English led to the failure for which Nivelle bore much responsibility. He was dismissed on 15 May 1917 together with Charles Mangin (1866-1925) and Olivier Mazel (1858-1940). The Brugère Commission, in charge of analyzing this failure, reached stalemate but clearly implicated the government’s responsibility.

When he came into office, Georges Clemenceau (1841-1929) forgot about the report and appointed Nivelle commander-in-chief in Algeria and the Sahara (January 1918). There Nivelle came proved useful in furthering the discovery of the Sahara and the recruiting of troops.

Post-War Career and Legacy↑

Back in France at the beginning of 1920 Nivelle was appointed to the Superior Council of War. He was in charge of various missions among which the representation of France at the celebration of the third centenary of the arrival of the first pilgrims in America.

The failure of the Chemin des Dames offensive, overemphasized by those in power, caused a polemic against Nivelle which did not end with his death. Remaining silent about the role of others in the affair, Nivelle thus let develop the thesis of his sole responsibility. Contrary to the current assertion, the Nivelle’s failure is but one of numerous explanations for the mutinies in the French army.

Denis Rolland, Soissons Historical Society

Section Editor: Alexandre Lafon

Notes

- ↑ Service Historique de la Défense 9Yd 651, dossier personnel Nivelle.

Selected Bibliography

- Commandant de Civrieux: Pages de vérité. L'offensive de 1917 et le commandement du général Nivelle, Paris 1919: G. Van Oest.

- Contamine, Henry: De quelques problèmes militaires de 1917, in: Revue d'histoire moderne et contemporaine 15/1, 1968, pp. 108-121.

- Galli, Henri: L'Offensive française de 1917 (avril-mai). De Soissons à Reims, Paris 1919: Garnier frères.

- Jagielski, Jean-François; Rolland, Denis: En terminer avec l'affaire du Chemin des Dames? La commission Brugère (1917), in: Fédération des sociétés d'histoire et d'archéologie de l'Aisne/LV , 2010, pp. 461-484.

- Painlevé, Paul: La Vérité sur l'offensive du 16 avril 1917, Paris 1919.

- Rolland, Denis: La grève des tranchées. Les mutineries de 1917, Paris 2005: Imago.

- Rolland, Denis: La question des pertes sur le Chemin des Dames, in: Mémoires de la Fédération des sociétés d'histoire et d'archéologie de l'Aisne 55, 2010, pp. 441-460.

- Rolland, Denis: Nivelle. L'inconnu du Chemin des Dames, Paris 2012: Imago.

- Rouquerol, J.: Le chemin des dames, 1917, Paris 1934: Payot.