Introduction↑

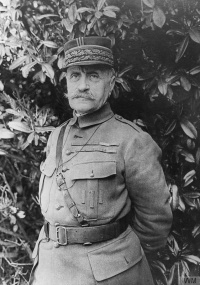

The Military Board of Allied Supply (MBAS), also known as the Inter-Allied Committee on Supply, was an effort to enable some measure of unified direction for the logistic support of allied armies in Europe during 1918. The German spring offensives drove the allied powers to unity of command of their field armies in France under the direction of Ferdinand Foch (1851-1929) on 26 March 1918, but the Doullens agreement overlooked the logistic support of those armies, which remained under each nation’s control. American pressure to create an agency that oversaw bulk supplies, military labor, transportation facilities, and overseas shipment of military goods themselves (though not the allocation of the shipping) led to follow-up agreements on 22 and 29 May that laid the groundwork for the MBAS, which first met formally on 28 June 1918.[1]

Aim and Achievements↑

The MBAS attempted to provide logistic oversight for allied armies in the field, but it lacked power unless its members were unanimous; this limited the Board’s ability to act. In early 1918, the British found themselves in the best logistic shape of the allied powers; some hostility to the MBAS resulted. The French were less well off after three hard years and the Americans were growing so fast and from such a small pre-war starting point that they simply needed more of just about everything related to logistic support. Not unreasonably, the MBAS focused its efforts on areas where agreement could be reached without too much acrimony.[2]

The MBAS managed to accomplish a number of things during its relatively brief existence. It pursued the goal of ensuring that all depots in France become capable of supporting any allied formation and created the first true allied inventory of storage facilities and their loading capacity.[3] The Board also implemented the British system of double-compressing hay and worked towards standardized ration scales, both human and animal, which allowed for more predictability on tonnage requirements dedicated to sustenance.[4] The follow-on from these enabled some intermingling of formations as needed on a tactical basis since each nation’s line of communications had some ability to resupply their allies with those allies’ requirements (tea, coffee or wine, for example).[5] Finally, the Board also managed to come to grips with and quantify the multitude of departments that supported a modern army – timber and logging, rail and road construction, medicine and numerous others.[6] A fascinating example is the mail service. During late 1918 the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) handled roughly 24 million letters per week, the French nearly 4 million per day, and the American effort peaked in October 1918 with over 51 million letters handled that month.[7] At roughly 64 million letters per week this meant sixty-four metric tons of shipping space per gram of the average letter or postcard - a small modern post card masses three to four grams. This illustrates the vast scope of the Board’s task, however, since mail made up a tiny portion of the overall demand.

Conclusion↑

Coalition warfare is among the most trying forms of warfare for nation states. Politically and strategically it is far easier to fight alone or as the unquestioned dominant power than to fight as merely one amongst a number of near-equals. Given unlimited resources members of a coalition could fight as each saw fit; this is not the reality of warfare. The MBAS was an approach to the theater-level challenges posed by the allied powers’ limited resources during the First World War. On the balance the Board proved successful; no troops starved, allied battles in Western Europe progressed with ever greater intensity and scope, and some groundwork was laid for the future. Had the war continued into 1919 it is probable that the Board would have exerted increased influence over the functioning of allied supply lines.

Ian M. Brown, Independent Scholar

Section Editor: Mark E. Grotelueschen

Notes

- ↑ Dawes, Charles G.: A Journal of the Great War, Vol. 1, Boston and New York 1921, diary entry 13 April 1918, pp. 84-90; Appendix A, 5 May 1918, pp. 284-287; Greenhalgh, Elizabeth: Victory through coalition: Britain and France during the First World War, New York 2005, pp. 234-235. Allied and Associated Powers, Report of the Military Board of Allied Supply, Vol.1, Washington 1924, p. 452.

- ↑ Dawes, Journal Vol.1 1921, Appendix A, 22 May 1918, pp. 295-296. Greenhalgh, Victory 2005, pp. 235-236. Allied and Associated Powers, Report Vol.1 1924, p. 452.

- ↑ Allied and Associated Powers, Report Vol.1 1924, p. 454.

- ↑ Allied and Associated Powers, Report Vol.1 1924, pp, 472-482, 536-437. In spite of its name, double-compression actually reduced volume by only about 30 percent.

- ↑ Greenhalgh, Victory 2005, p. 237.

- ↑ Cf. the exhaustive table of contents of Allied and Associated Powers, Report, Vol.2.

- ↑ Allied and Associated Powers, Report Vol.2, pp. 1074-1088.

Selected Bibliography

- Dawes, Charles Gates: A journal of the Great War, 2 volumes, Boston 1921: Houghton Mifflin.

- Greenhalgh, Elizabeth: Victory through coalition. Britain and France during the First World War, Cambridge; New York 2005: Cambridge University Press.

- Military Board of Allied Supply / Military Board of Allied Supply: Report of the Military Board of Allied Supply, 2 volumes, Washington, D.C. 1924: Government Printing Office.