Introduction: First phase until the battle of Shuʿayba↑

The two main problems of legitimacy regarding Ottoman rule in Iraq were that the majority of the population was Shiite and that a considerable percentage of the population belonged to tribes. Many of these tribes were partly or wholly Shiite. Thus, the Ottoman army in Iraq was tasked not only with safeguarding the border with Iran (which continued to be ill-defined and a source of constant irritation between the two countries), but it had the more important duty of holding the larger Iraqi tribes at bay. Although some tribes, like the Muntafiq or the Zubayd, supported the Ottoman side, most acted in their own interests.

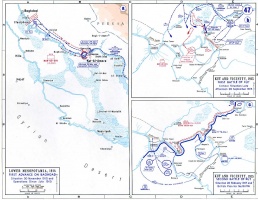

The Ottoman military leadership obviously did not expect a British attack on southern Iraq. In September 1914, Ottoman regular forces in all of Mesopotamia numbered not more than 23,000 men. Along with southern Iraq, the British occupied Mascat and Oman and following this took Basra with little difficulty on 23 November 1914 and Qurna at the conjunction of Euphrates and Tigris on 11 December.

Faced with this situation, the Ottoman defense strategy for Iraq was based on the concept of including large numbers of irregular forces of local tribes into the Ottoman forces. The governor of Baghdad, Cavid Pasha (1870-1932), who had been critical of the deployment of local Iraqi militia in Ottoman service, was replaced by Süleyman Askeri Bey (1884-1915) who was the head of the Teşkilat-i mahsusa and a friend of Ismail Enver Pasha (1881-1922). The test for the new Ottoman military strategy in Mesopotamia came with the battle of Shuʿayba in southern Iraq on 14 April 1915. The Ottomans had gathered a considerable number of irregular tribal forces in order to retake Basra but these proved inadequate in battle. Süleyman Askeri committed suicide once he realized the battle was lost.

Failures of the first British advance to Baghdad and of the relief of Kūt al-ʿAmāra↑

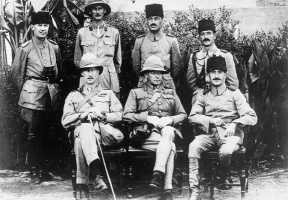

Süleyman Askeri was replaced by Colonel Mehmed Nureddin Ibrahim (1873-1932), known as Nureddin Bey and later Nureddin Pasha, who followed a policy which relied to a much lesser degree on tribal military support. When the British advance under the command of Charles Townshend (1861-1924) with a force of about 14,000 threatened Baghdad, he was able to obtain considerable reinforcements through regular Ottoman troops brought in from Syria and Anatolia. Thus, he was able to deploy about 18,000 troops in the battle of Ctesiphon on 22 November 1915, which marked the failure of the first British advance up the Tigris. Townshend decided to retreat to the town of Kūt al-ʿAmāra on the Tigris where his mostly Indian troops were surrounded and besieged by the Ottomans.

Meanwhile, the Ottoman troops in Mesopotamia had been reorganized as the 6th Army and its command had been given to the renowned German military theorist and general Colmar von der Goltz (1843-1916). Goltz soon quarreled with Nureddin, who had retained his position as governor of Baghdad, but as a military commander was now subordinated to Goltz. Enver's uncle Halil Kut Pasha (1881-1957) consequently replaced Nureddin. When Goltz died of typhoid on 19 April 1916, Halil Pasha took over the supreme command of the 6th Army. Halil Pasha adopted the return of Ottoman forward-strategy in Iraq that had been abandoned after the death of Süleyman Askeri.

Following the failure of several British relief expeditions, the besieged British troops in Kūt al-ʿAmāra surrendered on 29 April 1916. Out of over 13,000 soldiers, 70 percent died in Ottoman captivity.

Stalemate on the Tigris and the situation on the Euphrates↑

After Townshend’s capitulation, the command of the British-Indian troops in Iraq was given to Frederick Stanley Maude (1864-1917). Both the Ottoman military leaders and the German Generalstab believed that, at least for a considerable time, the British would not try to re-approach Baghdad. On the other hand, neither the Ottoman nor the German generals were seriously considering the option of clearing British forces out of Iraq. Instead, they embarked on an adventure of mutual rivalry in conquering and occupying Iran. Although it is true that until the beginning of the revolution in Russia in March 1917, the Russian troops in Iran remained a threat for Mesopotamia, there is evidence that at least Halil Pasha was pursuing the old plans of marching against India by means of forging an alliance with the emir of Afghanistan. On the other hand, Enver ordered Halil Pasha to prepare for another march against Russia which was intended to be backed mostly by a large-scale rebellion of Nicholas II, Russian Emperor’s (1868-1918) Muslim subjects.

Although the Euphrates constituted a main supply route, the main theater of war was concentrated along the course of the Tigris. In May 1915, the town of Najaf rebelled against the Ottomans. This was followed by other towns on the Euphrates, Karbala, Hilla, Kufa, Shamiyya and Tuwarij (with the exception of Diwaniyya) and caused Ottoman punitive measures.

The Fall of Baghdad on 11 March 1917↑

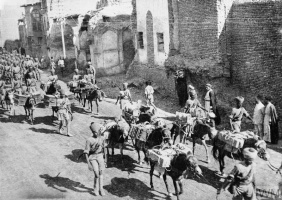

On December 1916, 50,000 British troops started a second, this time slow and systematic, offensive up the Tigris. Not only were they now far better equipped than their Ottoman adversaries were, but they outnumbered them five to one. In addition, the transfer of the Ottoman 13th Corps stationed in Hamadan to Iraq began so late that the Ottoman troops from Iran reached Mesopotamia only shortly after the fall of Baghdad. After Ottoman troops had to evacuate Kūt al-ʿAmāra on 24 February 1917, it became clear to Halil Pasha that he would not be able to hold Baghdad. Ottoman troops and their German allies finally evacuated Baghdad on 10 March 1917. The Ottoman headquarters in Iraq were transferred to Mosul. Despite facing strong resistance, British troops advanced as far as Samarra, taking control of the only finished segment (between Baghdad and Samarra) of the Baghdad railway in Mesopotamia. More territorial gains were made in the spring of 1918 but the offensive on the Mesopotamian front was resumed only with the beginning of negotiations for a ceasefire and quickly let to the complete breakdown of the Ottoman front on the Tigris. However, British forces only occupied Mosul after the armistice, on 4 November 1918.

Great Britain deployed more than 400,000 men in Mesopotamia in 1918 and from 1914 to 1918 lost more than 30,000 soldiers there. Presumably, the death toll on the Ottoman side and among irregular militia, tribes and civilians, for which no reliable estimations exist, was considerably higher. This period of warfare in Iraq cost Great Britain an estimated 150 million pound sterling. Economically, it took the region many years to recover from the impact of the war.

Christoph Herzog, Otto-Friedrich-Universität Bamberg

Section Editor: Pınar Üre

Selected Bibliography

- Gardner, Nikolas: The siege of Kut-al-Amara. At war in Mesopotamia, 1915-1916, Bloomington 2014: Indiana University Press.

- Herzog, Christoph: The Ottoman politics of war in Mesopotamia, 1914-1918, and popular reactions. The example of Hilla, in: Gara, Eleni / Kabadayı, M. Erdem / Neumann, Christoph K. (eds.): Popular protest and political participation in the Ottoman empire. Studies in honor of Suraiya Faroqhi, Istanbul 2011: Bilgi University Press, pp. 303-318.

- Larcher, Maurice: La guerre turque dans la guerre mondiale, Paris 1926: Berger-Levreault.

- Majd, Mohammad Gholi: Iraq in World War I. From Ottoman rule to British conquest, Lanham 2006: University Press of America.

- Moberly, F. J.: The campaign in Mesopotamia 1914-1918, 4 volumes, London 1923-1927: Her Majesty's Stationery Office