Pre-World War I↑

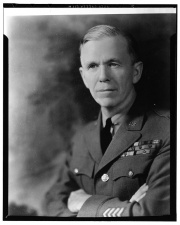

Prior to World War I, George Catlett Marshall’s (1880-1959) career was typical of a junior officer in a small, peacetime army. Overseas postings to the Philippines bookended his pre-war service and taught him much about small unit leadership and, according to his biographer, saw him develop an early reputation as a “highly resourceful young officer.”[1] Marshall also took opportunities to broaden his military education, producing an insightful report based on his touring of the Mukden battlefields whilst on leave in Manchuria in 1913. He graduated first in his class at the end of his first year at Fort Leavenworth, guaranteeing his place at Staff College as a result. Even so, by the fall of 1916 Marshall was still only a captain and watched the unfolding events in Europe with a keen professional interest.

In France↑

With the 1st Infantry Division↑

Marshall’s time in France with the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) shaped his attitudes towards both what was needed in the age of industrialized warfare as well as for the peace to follow. He earned the nickname “the wizard” for his crisp staff work and logistical brilliance. Marshall realized his ambition to serve in Europe when General William L. Sibert (1860-1935), took command of the 1st Infantry Division and requested that Marshall serve as assistant chief of staff, G-3 (Operations). Captain Marshall was the second American soldier ashore in France, after Siebert, at St. Nazaire on 26 June 1917.

Serving as the G3 of the 1st Division gave Marshall an early appreciation for the realities of military “unpreparedness”, a recurring concern he would grapple with throughout his career. Early on, Marshall dealt with equipment shortages, the need to find and secure adequate billets and training areas, a lack of discipline amongst the troops, and the need to manage the expectations of the French who, Marshall noted in his account of the time, believed the 1st Division to be “the cream of the Army.”[2] Multiple challenges arose in training fresh troops. Provisions of almost everything from billets to weapons were inadequate, and inevitably raised tempers and frustrations added to an already difficult environment. Marshall’s career-defining incident occurred in early October 1917 when General John J. Pershing (1860-1948) inspected the 1st Division headquarters and publicly rebuked General Siebert for the shortcomings he observed. Marshall, serving as acting divisional chief of staff, intervened on behalf of Siebert and quite forcibly refused to back down, even as General Pershing made to leave. Although Marshall’s fellow officers thought it the end of his career, his courage and candor impressed Pershing.

The 1st Division entered the frontlines as a full division in January of 1918. Marshall’s own account of this period is replete with the many challenges of the bitter winter that year, and of coming to terms with the reality of the war in the trenches. However, it is also full of the many, often small, progressive improvements apparent amongst the troops, as well as their growing fighting prowess. Seeking to pre-empt the slow but substantial build-up of fresh American troops, the German offensive of March that year struck a blow at the point where the British and French forces met. As part of the desperate Allied efforts to stem the German advance, the four combat-ready US divisions were deployed under British and French commanders, with Pershing’s acquiescence. By May of 1918, the German offensive had stalled and the 1st Division was well placed to aid in the Allied counter attack.

Marshall played a vital role in planning the 1st Division’s first successful actions against a small German salient on 28 May 1918 at the Battle of Cantigny. Although Marshall was promoted to lieutenant colonel, he was unable to secure an elusive combat command that would have earned him a promotion to full colonel. Marshall’s superiors repeatedly rejected his requests for combat command. General Robert Lee Bullard (1861-1947), who took command of the 1st Division in early December, prefaced his denial of Marshall’s request with, “Marshall’s special fitness is for staff work… I doubt he has an equal in the Army today”.[3] By way of consolation, Marshall was reassigned to a role as a staff member of the 1st Army and General Pershing's GHQ where these talents would have more influence.

St. Mihel and Meuse-Argonne↑

In August, the US units came together again as part of the 1st American Army and in September 1918, Marshall and others planned the beginning of a series of engagements as part of a wider allied offensive known as “The Hundred Days”. As a result, the US Army in France would be committed to battle more or less constantly for the rest of war.

Marshall, with Colonel Fox Conner (1874-1951) and Colonel Hugh Drum (1879-1951), planned operations against the German salient of St. Mihiel and then immediately shifted north between the Meuse river and Argonne forest. Fundamentally, the challenge was to move more than half a million American troops, nine divisions, together with several thousand artillery pieces, nearly 1 million tons of munitions and supplies, away from St. Mihiel, while allowing them to be relieved by other allied units. These forces moved sixty miles north, replacing nearly 250,000 troops from the French 2nd Army who needed to move away from the front as the Americans came in four days before the battle began. It was vital to do this in a fashion that did not alert the ever-watchful Germans. Marshall had only three narrow dirt roads and three light railways at his disposal. He also made much use of French trucks and French drivers. Marshall’s plan included illuminated signs at crossroads, vital at night when the movements necessarily had to take place. Problems related to moving motor vehicles, marching troops and horse drawn wagons and guns at different speeds were partially obviated by restricting different modes of transportation to discrete roads. Marshall consistently exhibited a tactical flexibility especially in dealing with the differing attitudes and procedures apparent amongst French troops under his command. The Franco-American Meuse-Argonne Offensive began on 26 September. It owed much to Marshall’s skills as a logistician and his ability to navigate the challenges of different armies and different languages. The Meuse-Argonne Offensive, together with other Allied offensives, finally shattered German resistance on the western front.

Post-war↑

Marshall achieved the (temporary) rank of full colonel in September 1918, and in October again took up the role of chief of operations for the 1st Army. Marshall had forged a substantial reputation but promotion remained slow. In 1920, Marshall’s temporary ranks were rescinded and he reverted to (albeit permanent) major. Despite having been on the cusp of being appointed a (temporary) brigadier near the war’s end, Marshall would not attain that rank permanently until 1936. Marshall served as United States army chief of staff during World War II and later as secretary of state under President Harry Truman (1884-1972), when he was partly responsible for the European Recovery Program, better known as the Marshall Plan.

Rob Havers, George C. Marshall Foundation

Section Editor: Lon Strauss

Notes

- ↑ Pogue, Forrest C.: The Education of a General 1880-1939, p.76.

- ↑ Brigadier James L. Collins in the introduction to Marshall, George C.: Memoirs of My Services in the World War, 1917-1918, Boston 1976, p. vii.

- ↑ Lt. General Robert L. Bullard quoted in Pogue, Forrest C.: The Education of a General 1880-1939, New York 1963 p.168.

Selected Bibliography

- Bland, Larry I. (ed.): The papers of George Catlett Marshall. 'The soldierly spirit', volume 1, Baltimore 1981: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Lengel, Edward G.: To conquer hell. The Meuse-Argonne, 1918. The epic battle that ended the First World War, New York 2009: Henry Holt and Co.

- Marshall, George C.: Memoirs of my services in the world war, 1917-1918, Boston 1976: Houghton Mifflin.

- Marshall, George C. / Pogue, Forrest C.: George C. Marshall. Interviews and reminiscences for Forest C. Pogue, Lexington 1986: George C. Marshall Research Foundation.

- Pogue, Forrest C.: George C. Marshall. Education of a general, volume 1, New York 1963: Viking Press.

- Stoler, Mark A.: George C. Marshall. Soldier-statesman of the American century, Boston 1989: Twayne Publishers.