Overview and Early Career↑

Commander-in-Chief of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) December 1915 to April 1919, Douglas Haig (1861-1928) was acclaimed by the historian John Terraine (1921-2003) as a “great captain,” the victor of 1918, but, because of his conduct of attritional battles such as the Somme and Third Ypres, he has been denounced by many as a callous and incompetent butcher. Recent scholarship has tended to steer a course between those two extremes. Today historians are divided between those who emphasise his faults and those who, while acknowledging his mistakes, point towards his achievements.

Douglas Haig was born in Edinburgh in 1861, the son of a wealthy whisky manufacturer. He attended a public school and the University of Oxford. After Sandhurst, where he was the outstanding student, Haig joined the 7th Hussars in 1885. Haig proved an excellent regimental officer and his diligence and professionalism caught the eye of senior officers. In 1897 Haig attended the Staff College, Camberley. As at Sandhurst, he stood out as a student. The notion that on the Western Front Haig stuck rigidly to the principles he had learned at Staff College is dubious.

Haig served in the Sudan campaign of 1898, fighting at the Battle of Omdurman. His next active service was in the Second South African War. Arriving in 1899 as chief of staff to his patron, Major-General John French (1852-1925), who commanded the Cavalry Division, Haig served in theatre until 1902. He emerged from the war with the reputation of a rising star, having commanded in the field as well as carried out important staff work.

World War One↑

Haig spent the next decade mostly in demanding staff and administrative jobs. These included acting as the principal military lieutenant to the Liberal Secretary of State for War Robert Burdon Haldane (1856-1928) during the latter's far-reaching reforms of the army, and overseeing the writing of a modern doctrine for the army. In August 1914 Lieutenant-General Sir Douglas Haig took I Corps to war. His conduct of operations in the initial stages was patchy, but his calm generalship on the defensive during the First Battle of Ypres (October-November 1914) was widely admired. As commander of the newly-formed First Army, in 1915 Haig (promoted to full general in November 1914) had to grapple with the unfamiliar conditions of trench warfare. He launched four major offensives. For a variety of reasons, none succeeded and losses were heavy. In each case Haig tried to apply the perceived “lessons” of combat. The aftermath of the Battle of Loos (September) was that Haig replaced French, his former patron, as Commander in Chief.

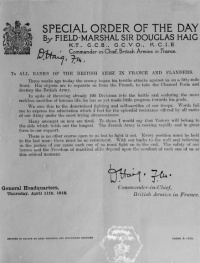

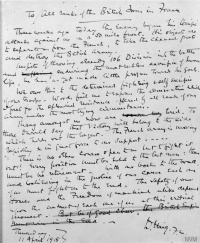

Haig, who became a field-marshal In December 1916, commanded the BEF during the great attritional battles of the Somme, Arras and Third Ypres (Passchendaele) in 1916-1917 He has been much criticised for setting over-ambitious objectives for his troops, and excessive optimism. His defenders point to the enormous challenges he faced, and to some extent successfully overcame, and the damage his offensives did to the German army. A fair assessment needs to take into account both sides of the argument and to place Haig's generalship into the wider context of the First World War. In recent years, some historians have stressed Haig's success as a war manager, overseeing the transformation of the BEF from the clumsy and inexperienced force of 1916 to the highly effective army of 1918.

David Lloyd George (1863-1945), Prime Minister from 1916-1918 thought little of Haig and tried to undermine the Commander in Chief's authority. Despite this, Haig held onto his job. He weathered the German offensives of early 1918. During the Hundred Days campaign (August-November 1918) Haig established a productive, if tetchy, relationship with Ferdinand Foch (1851-1929), appointed as Allied Generalissimo in April. Both men played a key role in the Allied victory. Haig returned to Britain in 1919 as a national hero. His stock rose even higher as the champion of ex-servicemen in the 1920s. He died just before the literary and cultural backlash against the war set in and his reputation soon collapsed.

Reception↑

In his Final Despatch (1919) Haig made a powerful case that his attritional campaigns had made the victories of 1918 possible. While this is an ex post facto argument (it is clear that at various times he expected to break through the trenches and restore mobile warfare) it is not entirely wrong. Although Haig made mistakes which had bloody consequences, he was not the idiot of myth. He had a lively appreciation of the importance of technology and recent research has argued that his operational concepts, including the use of cavalry, were sound. Above all, in 1918 he was a highly successful commander. Undoubtedly, Douglas Haig will continue to provoke academic debate for years to come.

Gary Sheffield, University of Wolverhampton

Section Editor: Catriona Pennell

Selected Bibliography

- Bond, Brian / Cave, Nigel (eds.): Haig. A reappraisal seventy years on, London 1999: Leo Cooper.

- Haig, Douglas Haig, Sheffield, Gary / Bourne, John M. (eds.): Douglas Haig. War diaries and letters, 1914-1918, London 2005: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

- Harris, J. P.: Douglas Haig and the First World War, Cambridge; New York 2008: Cambridge University Press.

- Sheffield, Gary: The chief. Douglas Haig and the British army, London 2011: Aurum.

- Terraine, John: Douglas Haig. The educated soldier, London 1963: Hutchinson.