Ethiopian-European Relations: Political Context to 1914↑

The rulers of the “Christian Kingdom of Abyssinia”, mostly located in the Ethiopian Highlands,[1] already had contact with European monarchs in the Middle Ages. Embassies were sent and received from both sides, with Portugal, the Vatican, and Russia having the oldest ties with Ethiopia. In the 19th century, this mutual awareness became more formalised.

In 1841, two years after the installation of the British in Aden, the first treaty was concluded between the British and a ruler of present-day Ethiopia. However, in the late 19th century, Europeans were hesitant to recognize Ethiopia as a sovereign member of the “family of nations”, to use a contemporary expression. During a period when Africans were generally relegated by European politicians and academics to the place of “the uncivilized”, Ethiopian rulers, despite their Christian faith, found it challenging to gain a place for their country at the table of “civilized” states.

Still, in 1884, Ethiopia’s future Negusä Nägäst Menelik II (1844-1913) signed a treaty with the British over their respective spheres of influence in the upper Nile region.[2] In 1889, Menelik concluded a treaty of friendship and commerce with the Italians (the treaty of Wəčale or Trattato di Uccialli).[3]

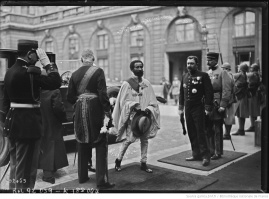

Considering these processes of Ethiopian-European rapprochement and Menelik’s own expansionist agenda, historians speak of “Ethiopia’s success… to have actively participated as the only African state in the partitioning of the continent”.[4] Menelik saw himself as a monarch of equal standing with his European “brothers”. However, the Italians interpreted the treaty of Wəčale to have established an Italian “protectorate” over Ethiopia, an interpretation Menelik disputed. When, in 1896, the Italians felt strong enough to compel the rebelling “protectorate” into their colonial order, Emperor Menelik beat General Oreste Baratieri (1841-1901) in the Battle of Adwa (1 March 1896). Following this victory and a treaty with Italy recognizing Ethiopia’s sovereignty and annulling the treaty of Wəčale, Menelik followed a non-committal foreign policy. His goal was to strengthen his sovereignty (the principle of a government by ministries was introduced in 1905-1906) and to use the competition of his European neighbours, Italy, Great Britain, and France, to Ethiopia’s advantage. Subsequently, Britain, France, Italy, Belgium, Russia, the United States, Germany, and later the Ottoman Empire set up legations in the new capital Addis Ababa. From then on, Ethiopia was on the map of international politics and Germany in particular tried to increase its political and economic influence during the decade before 1914. In 1907, an Ethiopian mission visited Budapest, Vienna, and Berlin.[5]

Ethiopia during the First World War↑

Neutrality?↑

War against Italy seemed in Ethiopia's interest and therefore joining the war on the side of the Allies was seriously considered in Addis Ababa. Following the death of Menelik II in 1913, crown prince and regent Lïj Iyasu (1897-1936) assumed power, while opposing political circles in Addis Ababa – with different preferences regarding the European powers – struggled for influence or even aimed at replacing Lïj Iyasu.[6] When war seemed imminent in July 1914, it also seemed likely that the French and British legates would outmanoeuvre their German counterpart and succeed in convincing the crown prince to support the Allies. Rumour had it that the Ethiopians would join Allied war efforts, out of their own interest in finally gaining access to the Red Sea at the expense of the Italians in Eritrea. Provided France and Great Britain declared war on Italy – since 1882 diplomatically tied to the Central Powers by virtue of the Triple Alliance – Ethiopia would attack Eritrea, as the Italians also feared.[7]

However, as previously, when war broke out in Europe Ethiopia’s political elite attempted to follow a multilateral approach that fended off pressures to discriminate against citizens of the warring states. This (undeclared) neutrality – and the question of what rights and duties this entailed – remained disputed between the foreign legates and the Ethiopian government, irrespective of the fact that, in 1914, Ethiopia had not yet ratified the Hague Convention “relative to the rights and duties of neutral powers and persons in case of war on land” (1907). For example, from August 1914, the Allied legates exerted pressure on the Ethiopian government so that citizens of the Central Powers in Ethiopia would be barred from using post offices, telegraphs, Addis Ababa's only printing press, and even the railway line to French Djibuti.

Fighting for the Central Powers?↑

With the Italians joining the Allies in April 1915, all of Ethiopia’s neighbours were involved in the war fighting Germany and its ally, the Ottoman Empire, with its Yemeni colony at the opposite side of the Red Sea. Yet, in 1915 and 1916, sympathies towards the Central Powers among a faction of Ethiopia’s leading political circles became more outspoken. The Central Powers hoped to open new fronts against the British in Sudan and Somalia, not only in Libya, where, from November 1915, the Sanussi – with Turkish support – had launched an attack upon Anglo-Egyptian troops. To this end, Ethiopian support was crucial, as it was hoped the Ethiopians would deliver weapons to the Sanussi and Mohammed Abdullah Hassan (1856-1920), known derogatorily in Europe as the “Mad Mullah” in Somalia. The Central Powers promised the Ethiopians not only their own attack on the Suez Canal, but also that Ethiopia could, after the war, keep any outlet to the sea that Lïj Iyasu conquered. The Germans even hoped that Ethiopia could relieve Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck's (1870-1964) troops fighting in German East Africa.

The Allies were aware of Germany’s and Turkey’s plans to use Pan-Islamic convictions in the Arab world and beyond against their adversaries. In June 1916, the Turkish Consul Aḥmed Maẓhar bey distributed leaflets in Addis Ababa, which concluded that “[t]he interests of Islam in this country concur with those of the Abyssinian Government.”[8] There were rumours, possibly fuelled by Allied supporters, that the crown prince would convert (or had already converted) to Islam. Lïj Iyasu’s affiliation to the Turkish consul and Muslim notables in Harar, Ethiopia, but also beyond in Somalia became a grave concern for the British and French legations. Whereas the Ethiopian minister of war preferred a policy of neutrality, Lïj Iyasu apparently gambled on the victory of the Central Powers.

British diplomats around the world pressed for a more favourable attitude among neutrals towards the Allied war efforts that, for example, would allow the provisioning of Allied troops. Considering the Turkish-German attempt to get Ethiopia on their side, the Allied legates in Addis Ababa used their better access to the power brokers of Ethiopia around Lïj Iyasu's cousin Ras Tafari Makonnen, the future Haile Selassie I, Emperor of Ethiopia (1892-1975). As both cousins could claim descent from the Solomonic line, they had already been competitors to the throne for years when Ras Tafari initiated the successful coup d’état of 26 September 1916 against Lïj Iyasu. The coup was supported by the Allies and justified with Iyasu's alleged “conversion to Islam” – however, despite charges of apostasy the available evidence “in no way suggest[s] a formal conversion” or that Iyasu gave up “his Christian identity”. Given the Allied military dominance in the region in 1916, Ras Tafari considered the political leanings of the deposed crown prince towards Turkey as suicidal for Ethiopia's independence. Subsequently, Lïj Iyasu was put under house arrest and, following his escape, put into prison.[9]

Under the new empress (Queen of Kings [Negiste Negest]) Zauditu, Empress of Ethiopia (1876–1930), a cousin to both Lïj Iyasu and the new heir apparent Ras Tafari, Ethiopia remained neutral in the ongoing war. The government consequently even prohibited (in line with the Hague Conventions) the recruitment of Ethiopians into Allied forces in 1917. Ethiopian farmers were, nevertheless, allowed to sell their cattle to the meat factory in Eritrea, which provisioned the Italian army. When, in May 1917, a small German party attempted, on behalf of the German legation in Addis Ababa, to cross the Red Sea in order to transport messages to the Turkish army, the French legate accused the Ethiopian government, after the Germans had been arrested in Djibuti, of a “flagrante violation de neutralité”.[10]

Siding with the Allies↑

In June 1917, the Ethiopians under Ras Tafari offered the Allied legates that Ethiopia would break off all relations with the Central Powers, but demanded the delivery of 16,000 modern rifles. The Italian government, however, convinced their allies that a neutral but friendly Ethiopia was more helpful than an additional but “unnecessary” brother-in-arms who would make unwanted claims during the peace negotiations, based on strengthened sovereignty and an unwelcome sense of equality. Ethiopia's offer was thus turned down.

In late 1918, the Ethiopian government congratulated the Allies on their victory, but the German legation in Addis Ababa was not closed down. In May 1919, the Allies only provided a lukewarm welcome to an “Abyssinian mission” in Rome, Paris and London. France was in favour of Ethiopia joining the League of Nations; however, Italy and Britain, still hesitant to unequivocally accept Ethiopia’s statehood, opposed such a step. It was only in 1923 that this African state was admitted to the league. Here Ethiopia continued to struggle diplomatically to maintain its independence.[11]

Jakob Zollmann, The WZB

Section Editor: Michelle Moyd

Notes

- ↑ Ethiopia and Abyssinia have been used in European maps as synonyms since the early modern period and until the middle of the 20th century. The terms derive from Greek (Αἰθιοπία – country of the burned faces) and Hieroglyphic Egyptian ('Hbsty – designating a southern country, the term can be found also in Sabean sources), respectively. See Voigt, Rainer: Abyssinia, in: Encyclopaedia Aethiopica, volume 1, Hamburg 2003, p. 59.

- ↑ Negusä Nägäst (Ge'ez: ንጉሠ ነገሥት) means King of Kings (of Ethiopia), and was mostly translated as “emperor” in the 20th century.

- ↑ Hatem Elliesie: Völkerrechtliche Beziehungen zwischen Äthiopien und Italien im Lichte des Vertrages von Uccialli/Wuchale (1889), Cologne 2017.

- ↑ Marx, Christoph: Geschichte Afrikas. Von 1800 bis zur Gegenwart, Paderborn 2004, p. 69.

- ↑ See Zollmann, Jakob: Ethiopia, International Law and the First World War. Considerations of Neutrality and Foreign Policy by the European Powers, 1840-1919, in: Shiferaw Bekele et al. (eds.): The First World War from Tripoli to Addis Ababa (1911-1924), Addis Ababa 2019, pp. 115-152.

- ↑ See Ficquet, Éloi / Smidt, Wolbert G. C. (eds.): The Life and Times of Lïj Iyasu of Ethiopia, Münster 2014.

- ↑ See Gilkes, Patrick / Plaut, Martin: Great War Intrigues in the Horn of Africa, in: Shiferaw Bekele, The First World War from Tripoli to Addis Ababa 2019, pp. 37-58.

- ↑ Quoted in Erlich, Hagai: From Wello to Harer. Lij Iyasu, the Ottomans, and the Somali Sayyid, in: Ficquet The Life and Times of Lïj Iyasu of Ethiopia 2014, pp. 135-147 (here p. 139); see Loth, Wilfried / Hanisch, Mark (eds.): Erster Weltkrieg und Dschihad. Die Deutschen und die Revolutionierung des Orients, Munich 2014.

- ↑ Smidt, Wolbert G. C.: Glossary of Terms and Events of the Lïj Iyasu Period, in: Ficquet, The Life and Times of Lïj Iyasu of Ethiopia 2014, p. 185.

- ↑ Labrousse, Heinri: La neutralité éthiopienne pendant la Première Guerre mondiale. L’incident Holtz-Karmelich, in: Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference on Ethiopian Studies, Chicago 1977, pp. 525-546 (here p. 534).

- ↑ See Zaccaria, Massimo: La lunga strada verso Ginevra. L'Etiopia e la Conferenza della Pace di Parigi (1918-1919), in: Rivista italiana di storia internazionale II 1 (2019), pp. 31-54; Monin, Boris: The Visit of Rās Tafari in Europe (1924). Between Hopes of Independence and Colonial Realities, in: Annales d’Éthiopie 28 (2013), pp. 383-389; Parfitt, Rose: The Process of International Legal Reproduction. Inequality, Historiography, Resistance, Cambridge 2019, pp. 267-308.

Selected Bibliography

- Hatem Elliesie: Völkerrechtliche Beziehungen zwischen Äthiopien und Italien im Lichte des Vertrages von Uccialli/Wuchale (1889), Cologne 2017: Koppe.

- Labrousse, Heinri: La neutralité éthiopienne pendant la Première Guerre mondiale. L’incident Holtz-Karmelich, in: Hess, Robert L. (ed.): Proceedings of the fifth international conference on Ethiopian studies, session B, April 13-16, 1978, Chicago, USA, Chicago 1979: Office of Publications Services, University of Illinois at Chicago Circle, pp. 525-546.

- Scholler, Heinrich: German World War I aims in Ethiopia. The Frobenius-Hall mission: Recht und Politik in Äthiopien. Von der traditionellen Monarchie zum modernen Staat, Berlin 2008: Lit, pp. 42-65.

- Shiferaw Bekele / Uoldelul Chelati Dirar / Volterra, Alessandro et al. (eds.): The First World War from Tripoli to Addis Ababa (1911-1924), Corne de l’Afrique contemporaine / Contemporary Horn of Africa, Addis Abbaba 2018: Centre français des études éthiopiennes.

- Uoldelul Chelati Dirar: Attraversamenti di confini, politiche imperiali e strategie anticoloniali. L'attività del consolato etiopico di Asmara (1915-1936), in: Palma, Silvana / Volterra, Alessandro; Triulzi, Alessandro et al. (eds.): Colonia e postcolonia come spazi diasporici. Attraversamenti di memorie, identità e confini nel Corno d'Africa, Rome 2011: Carocci, pp. 187-208.