Introduction↑

On Easter Monday, 24 April 1916, over 1,000 poorly-armed Irish separatists occupied prominent buildings across the centre of Dublin, triggering a week-long battle for what was then one of the major cities of the United Kingdom. Confronted by over 20,000 British troops, many of Irish nationality, the rebels had no chance of military success. The rebellion ended in six days, leaving almost 500 dead and much of the city centre in ruins. In response, the British authorities executed fifteen of the ringleaders and arrested over 3,000 suspects.[1] An act of armed propaganda rather than a serious attempt to seize power, the rebellion changed the course of Irish history. Although the Rising was unpopular at the time, by 1917 large crowds were turning out in Dublin to greet rebels as they returned from British internment camps. When Sinn Féin swept aside the moderate nationalist Irish Parliamentary Party in the general election of 1918, its demand for the Republic proclaimed by the Easter rebels made inevitable the War of Independence (1919-21) and Civil War (1922-23) that followed. Despite controversies about the morality and legacy of the rebels’ actions, the Easter Rising is remembered as the pivotal event in the struggle for Irish independence.

Background: the Ulster Crisis, 1912-1914↑

As on previous occasions, the opportunity for revolution in Ireland stemmed largely from external factors. Ireland’s home rule (or Ulster) crisis resulted from the clash between the British Liberal government and the Tory-controlled House of Lords over David Lloyd George’s (1863-1945) 1909 “People’s Budget.” By reducing the Lords’ powers from an absolute veto to the ability to delay legislation for two years, the resulting Parliament Act (1911) paved the way for the introduction of home rule in Ireland. It also inadvertently incentivised a lengthy campaign of militant resistance to home rule centring on Protestant-dominated, pro-British Ulster. Unionist strategy initially prioritised propaganda and political mobilisation, the success of which was exemplified by the signing of the Ulster Covenant in September 1912. However, following the formation of the paramilitary Ulster Volunteer Force in January 1913, the importation of German rifles in April 1914 and the establishment of a “provisional government” in Belfast, there was considerable potential for conflict – whether with the British authorities or Irish nationalists – by the eve of the Great War.

The British government’s failure to prevent the formation of the Ulster Volunteers enabled nationalists to establish the Irish Volunteers and, by the summer of 1914, over a quarter of a million Irishmen belonged to paramilitary groups, vastly outnumbering Crown forces in Ireland. The popularity of volunteering reflected not only the depth of the political crisis but the appeal of military values across the political spectrum in pre-war Ireland.[2] Britain’s grip on Ireland was further weakened by the Curragh “mutiny” when British army officers resigned to protest the Liberal government’s apparent willingness to impose home rule on Ulster’s unionist majority. The inept handling of this incident led to the resignation of the Secretary of State for War, John Edward Bernard Seely (1868-1947), and the Chief of the Imperial General Staff, Sir John French (1852-1925), only months before the beginning of the war.

The outbreak of war postponed the threat of political and sectarian conflict in Ireland as nationalist and unionist leaders strove to demonstrate their loyalty to Britain. However, the First World War also ultimately created the opportunity for insurrection. Although the overwhelming majority of Irish Volunteers and Catholic nationalists supported the decision of the Irish Party leader John Redmond (1856-1918) to back the British war effort, Redmond’s political authority was increasingly eroded by the unfolding circumstances and experience of the war. The British Army’s more favourable treatment of Ulster Volunteer recruits, the formation in 1915 of a coalition government at Westminster comprised of die-hard Conservative and Unionist opponents of home rule, major losses among Irish units at Gallipoli and on the Western Front and growing fears of conscription undermined the Irish Party’s credibility.

Planning the Rebellion↑

For Ireland’s republican minority “England’s difficulty” proved “Ireland’s opportunity.” Three organisations were centrally involved in the Easter Rising: the radical faction of the Irish Volunteers that split from the main body when Redmond supported enlistment in the British army; the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) secret society, also known as the Fenians; and the Irish Citizen Army, a socialist militia established by militant trade-unionists during the 1913 Lockout. They were supported by other smaller groups including Na Fianna Éireann, a republican scouting organisation, and Cumann na mBan, a militant nationalist organisation for women that functioned as an auxiliary to the Irish Volunteers.

It was a small, secret faction within the IRB, known as the military council, that orchestrated the rebellion. Although regarded by some as moribund, the IRB had been revitalised following the return from the United States of veteran Fenian, Tom Clarke (1857-1916), and the emergence of a younger generation of revolutionaries. However, many Fenians – conscious of the insurrectionary debacles of 1848 and 1867 – opposed the idea of mounting a rebellion undertaken without public support or likelihood of success.

The Irish Volunteers, the largest of the three organisations, was also divided on the merits of a rebellion. A considerable proportion of its 10,000-15,000 militants (representing fewer than 10 percent of the original body) opposed an unprovoked rebellion. Since its inception, the purpose of the Volunteers had never been defined beyond a vague aspiration to defend the rights of Ireland, a formulation interpreted by republicans as equating to independence but more cautiously defined by figures such as Eoin MacNeill (1867-1945), the chief of staff of the Irish Volunteers.

Although later pilloried for sabotaging the Rising, MacNeill’s objections to insurrection were compelling. While prepared to support a rebellion that had a reasonable prospect of success, MacNeill argued that it was immoral to shed blood in an insurrection whose only rationale was propagandistic. Having methodically built up a military force, he believed that the Volunteers should await an act of British aggression, such as an attempt to introduce conscription or to disarm the movement. Others around MacNeill opposed the insurrection on more pragmatic grounds, arguing that the movement was better suited to guerrilla warfare than an 1848-style citizens’ revolt.[3] The military council bypassed these objections by recourse to the same methods that it used to circumvent those within the IRB who opposed an unprovoked insurrection: conspiracy and deception.

Of the three revolutionary bodies, it was only the smallest and least significant – James Connolly’s (1868-1916) Irish Citizen Army – that was fully committed to an unprovoked insurrection. As with the other members of the military council, Connolly’s motives were closely bound up with the impact of the First World War.

Rationale and Ideology↑

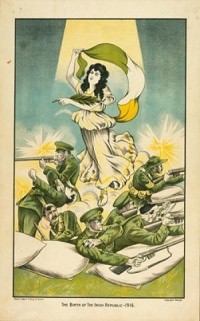

What did the rebels hope to achieve? Although prepared to die for Ireland, there is little to suggest that IRB conspirators like Tom Clarke or Seán MacDermott (1883-1916) willingly sought martyrdom despite the subsequent myth of the Rising as a “blood sacrifice.” They intended rather a principled, heroic gesture to reawaken the spirit of militant nationalism among the apparently apathetic masses, an aspiration that explains their preoccupation with symbolic and dramatic gestures, such as the proclamation of an Irish republic, over military objectives.

The rebels’ fatalism reflected the weakness of republicanism: they were motivated by their belief that the physical-force tradition, of which they saw themselves the guardians, was dying. In contrast to the “legion of the excluded” that rose in 1916,[4] most Irish nationalists were satisfied with home rule – a modest measure of devolution that would keep Ireland not merely within the Empire but within the United Kingdom – as a settlement of the demand for self-government. Popular nationalist support for the British war effort confirmed separatist frustration and pessimism. Evidence from the Bureau of Military History, an extensive archive of testimony recorded long after the Rising, offers many examples of this mentality. “It was nearly impossible to see a difference between Ireland and England,” one Volunteer recalled. “Something big should happen to awaken the country.” “The war was on, and Dublin citizens cheered the fellows going away at the North Wall,” a Dublin Fenian recollected. “Something must be done to save the soul of the nation.”[5]

The Great War provided the rationale – and pretext – for the Rising. As early as September 1914 its outbreak had allowed the militants within the IRB to persuade the hesitant Supreme Council IRB leadership to commit the organisation to rebellion despite unpropitious circumstances. Their arguments were entirely premised on the context provided by the war: a distracted Britain, a powerful ally and the promise from Germany of weapons, military assistance and diplomatic support. Even defeat, always the most likely outcome, might be transformed into political triumph when – as the rebels tended to assume – Germany won the war. Whether the insurrectionaries necessarily believed these arguments was moot: the war clinched the all-important debate within the separatist movement as to whether an insurrection should take place.[6]

The emotional aspects of the wartime context were arguably as important as the strategic. Eamonn Ceannt (1881-1916), one of the signatories of the Proclamation, spoke of the disgrace of allowing the war to pass without rising. Clarke argued that a failure to act, as his generation had failed during the Boer War, would be humiliating; Patrick Pearse (1879-1916), who would become president of the Republic, spoke of the shame and ridicule that would follow inaction. ‘”If this thing passed off without us making a fight I don’t want to live,” Seán MacDermott told a leading Fenian, “And Tom [Clarke] feels the same.”[7]

In short, the rebels were united in the belief that, in a time of war, action was preferable to inaction, that the advantages of an unsuccessful insurrection – the reassertion of separatist credibility, the survival of the physical-force tradition, the possibility of winning popular support and destroying home rule (as much the target of the Rising as the British) – outweighed the consequences of probable military defeat. Although their motives are sometimes depicted as irrational, history proved the military council correct as what must have seemed like a desperate roll of the dice reaped spectacular – if, for its leaders, posthumous – political dividends.

While indelibly identified with the progressive republican rhetoric of the Proclamation, the rebellion was in ideological terms a more incoherent product of the divergent coalition of secular republicans, Catholic intellectuals, cultural nationalists and socialists that brought it about. Beyond their belief in the necessity of violence to achieve a republic, it is difficult to discern much in the way of a specific ideological vision in the writings of the rebellion’s Fenian organisers, Clarke and MacDermott. Patrick Pearse – who, as President of the Republic, became the public face of the rebellion – epitomised the cultural nationalist values that pervaded the revolutionary generation, particularly in his commitment to the revival of the Irish language, seen as the essence of Irish nationality. Central also to Pearse’s outlook was an exaggerated militarism:

Such rhetoric, accompanied – in the case of Pearse and at least two other military council members – by a messianic belief in the necessity for a blood sacrifice, demonstrated the influence of a romantic nationalist sensibility prevalent among other European intellectuals of the “generation of 1914.”[9]

Like Pearse, Connolly – hitherto keen to emphasise the difference between revolutionary socialism and bourgeois nationalism – was radicalised by the advent of the Great War which shook his belief in the resilience of international working-class solidarity. By the eve of the Rising, Connolly’s rhetoric had assumed a strikingly sanguine tone: “no agency less potent than the red tide of war on Irish soil will ever be able to enable the Irish race to recover its self-respect.”[10] Underlying such rhetoric, however, could be discerned a more rational belief in the necessity for asserting revolutionary credibility through the use of violence.

The Battle for Dublin↑

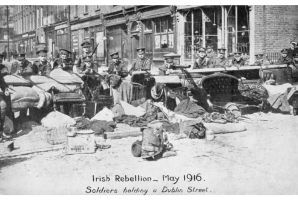

It is difficult to identify much in the way of a coherent military strategy underpinning the rebels’ tactics which consisted of garrisoning large buildings and awaiting the arrival of British soldiers with artillery. By the time the rebellion began on Easter Monday, however, the military council’s original plans had been overtaken by circumstances. The interception by the British Navy of a German arms shipment and Eoin MacNeill’s last-minute “countermanding order” to the Volunteers forced the military council to postpone the rebellion planned for Easter Sunday, derailing hopes for a wider insurrection. However, the shambolic collapse of Volunteer mobilisations in Cork, Limerick and Tyrone on Easter Sunday suggested there had never been much prospect of serious fighting outside Dublin. Many national Volunteer leaders were either ignorant of – or unconvinced by – the military council’s strategy.[11] Even in Dublin, a majority of the Volunteers – few of whom had advance knowledge of the rebellion – opted to remain at home throughout Easter week.

The rebels’ strategy has been much criticised from a military perspective. Important strategic and symbolic buildings, such as Trinity College and Dublin Castle, were overlooked. It is difficult to discern the rationale for locating garrisons at the South Dublin Union, a sprawling hospital for the poor, or St. Stephen’s Green, where rebels dug trenches that were overlooked by the surrounding buildings. Most garrisons saw little action, with fighting centring on the few areas where small outposts had been established to intercept the British forces that began to converge on the rebels by mid-week. Around half of the British Army’s casualties occurred as a result of a single engagement at Mount Street Bridge where, in a bizarre echo of the Western Front, vast numbers of British troops repeatedly (and unnecessarily) charged well-fortified rebel positions. In general, the military pursued a more cautious strategy of cordoning off rebel garrisons and bringing artillery to bear. Few rebel outposts had been directly engaged by British soldiers before artillery bombardment, raging fires and the military council’s concerns about civilian casualties prompted a general surrender on 29-30 April.

The rebels’ actions and statements during Easter week attest to the essentially symbolic nature of the Rising, as well as the influence of the Great War. The importance of the former dimension of the rebellion was most clearly grasped by Patrick Pearse whose proclamation of an Irish republic on Easter Monday provided – for posterity if not the bemused onlookers who witnessed the event – the defining moment of Easter week. An inspirational if somewhat fanciful call to arms, the Proclamation identified the rebellion with strikingly egalitarian values – including "religious and civil liberty, equal rights and equal opportunities" – that reflected the most idealistic strands of thought within the separatist leadership. These were not necessarily shared by many of the Irish Volunteers who fought at Easter week, or the Catholic nationalist masses subsequently won round to the aim of a republic.

Regarding the rebellion as a form of “propaganda of the deed,” aimed at mobilising both Irish and international support, the military council emphasised the need for a clean fight. The Proclamation urged the rebels not to dishonour their cause “by cowardice, inhumanity or rapine,” while Pearse declared that their “valour, self-sacrifice and discipline” would “win for our country a glorious place among the nations.”[12] Their belief that they were engaged in a legitimate form of war – crucial for their self-perception as a chivalrous military force – contributed to their enthusiasm for military trappings: rebels wore uniforms, mimicked formal army structures and titles and proclaimed themselves the lawful authority. Officers at the rebels’ headquarters in Dublin’s General Post Office (GPO) assigned themselves orderlies, aides-de-camp and adjutants; they ate in a commissariat and socialized in an officers’ mess. Female combatants – of whom there were around 200 – were confined to gendered roles scarcely less conventional than within regular armies, with one garrison refusing to permit entry to female rebels. While tactically dubious, the wearing (by some) of military uniforms, occupation of fixed locations and spurning of guerrilla methods added symbolic and moral weight to their protest in arms. The rebels’ desire to conform to idealized notions of conventional military behaviour was particularly evident during the surrender when many rebels chose not to escape.

In contrast, the decision to locate their insurrection within the densely-populated inner-city conflicted with the rebels’ perception of themselves as a conventional force fighting by conventional means. As with many other aspects of the rebellion, this decision appears to have reflected the rebels’ essentially propagandistic intentions. Headquartering the rebellion in one of the most prominent buildings on the capital’s main thoroughfare ensured that the event, choreographed by a military council of poets and dramatists, was experienced by thousands of Dubliners (and the international press) as a kind of revolutionary street-theatre.

The setting of the Rising also ensured that some 2,600 people were wounded, with civilians accounting for a majority of the rebellion’s roughly 482 fatalities.[13] Although the rebels occupied convents, hospitals and homes, bringing death and destruction to the innocent, their reaction to the pitiful plight of civilians when they finally witnessed this at first hand suggested an abysmal lack of foresight rather than a cynical intention to wreak havoc on Dublin’s civilians.

The British Army, rather than the rebels, were responsible for most of the civilian fatalities. Being few, poorly armed and largely confined to garrisons, the rebels were in little position to inflict harm. While most British Army soldiers behaved professionally, there were vastly more of them and they were heavily armed, mobile and dispersed over a wide area. Many were young, inexperienced and inefficient. One British army captain, who described the Sherwood Foresters under his command as “untrained, undersized products of the English slums,” noted that many “had never fired a service rifle before.”[14] The scale of civilian casualties was also a consequence of the army’s use of artillery and heavy machine-guns and its crude tactics: “The head of the columns will in no case advance beyond any house from which fire has been opened, until the inhabitants of such house have been destroyed or captured,” Brigadier-General William Henry Muir Lowe (1861-1944) ordered. “Every man in any such house whether bearing arms or not may be considered as a rebel.”[15] This punitive response was, like so much else, shaped by wartime considerations which ensured that little thought was given to the political consequences of what came to be seen as a heavy-handed repression.

In areas where the military encountered stiff resistance, such as North King Street where fourteen soldiers were killed and another thirty-three wounded in a twenty-eight-hour battle for control of 150 yards, the army appeared to regard any remaining residents as legitimate targets.[16] General Sir John Maxwell (1859-1929), the British General-Officer-Commanding-in-Chief , was candid about this aspect of the fighting in one press interview:

Maxwell’s comments reflected the confusion and frustration of street-fighting as British soldiers advanced through streets where they could be fired on by unseen snipers from almost any angle. They also highlight a revealing gulf between the rebels’ perception of their own conduct and the military’s view of the illegitimate nature of the rebellion and its methods. Significantly, it was the rebels’ belief that they had fought “in a fair and clean manner” that came to be widely shared by nationalist opinion.[18] As a result, the British authorities’ decision to execute leading rebels after the Rising was seen by many nationalists as akin to the shooting of prisoners of war.

Conclusion↑

Crucially, the scale of the rebellion proved sufficient to satisfy the military council’s political ambitions. The plight of the vanquished rebels, moreover, aroused more sympathy than their actions during Easter week. Although rebels were jeered, spat at and even attacked by Dubliners during the surrender, particularly in working-class neighbourhoods with high rates of army enlistment, public opinion shifted as the ringleaders were executed between 3 and 12 May.

Although frequently described as a draconian response, it was not the number of executions so much as their manner that alienated nationalist opinion: the speed and secrecy of what one prosecutor described frankly as “drumhead courts martial,”[19] the seemingly arbitrary nature of some of those executed - such as Patrick Pearse’s brother Willie Pearse (1881-1916) - and the piety and stoicism of the rebel leaders ensured their place among the pantheon of Irish martyrs. As the Irish Party leader, John Dillon (1851-1927), told the government in the House of Commons while the executions were continuing, “You are washing out our whole life work in a sea of blood.”[20]

The first evidence of growing sympathy for the rebels was the sight of crowds flocking to requiem Masses for the executed leaders who were almost instantly memorialised in ballads, mass cards, badges, flags, picture postcards and other relics.

The arrest of some 3,500 suspects, many innocent, also provoked popular indignation, leading to the emergence of prisoner welfare organisations, mainly run by women, to allow the public a safe means to express popular support for the rebels. Sympathy for the fate of the rebels developed into resentment of Irish Party politicians, moderate nationalists who were depicted as complicit in the executions.

Over time, this sentiment began to crystallise in more tangible forms. Rejection of constitutional nationalism – seen as hopelessly compromised both by the imperial rhetoric of Redmondism and by the party’s support for the war – was followed by the emergence of popular support for republicanism, understood as the demand for complete separation from Britain. In February 1917, George Noble Plunkett, Count Plunkett (1851-1948), the father of one of the executed rebels, defeated the Irish Party in a parliamentary by-election. Later that year, one of the prisoners, Eamon de Valera (1882-1975), was elected shortly after his release in July, as the Irish Volunteers and a revived Sinn Féin party emerged to lay the foundations for a broad political and military challenge to British power during the War of Independence (1919-1921).

Sentiment alone would not have transformed public opinion. The wider context of World War One was vital. The appointment of General John Maxwell in place of the civilian administration led by Irish Chief Secretary Augustine Birrell (1850-1933), who had resigned in disgrace, ensured that wartime expediency rather than political calculations determined British policy in Ireland after the Rising. The wartime context explains much that now seems inexplicable about the British response: the reckless frontal assault on Mount Street Bridge as waves of soldiers were cut down to the sound of officers’ whistles, the devastation of the city by artillery, the nationwide imposition of martial law, the peremptory nature of the drumhead courts martial and the counter-productive coercion that followed. The clearest example of how British military requirements – understandably prioritised by both the UK government and the army – destroyed the credibility of the Irish Party and created popular support for republicanism was the counterproductive attempt to impose conscription on Ireland in April 1918. As in other parts of the world, the impact of the war reconfigured political realities on the home-front, with imperial power giving way to a new world order based on popular sovereignty.

By magnifying the tensions between British requirements and Irish national interests, the rebellion exposed the limitations of the home rule project. Nationalists had supported home rule not because it fulfilled their aspirations but because it appeared to be all that could realistically be achieved. In contrast, violence seemed not only futile but counterproductive. The Rising shattered both assumptions. Less than a month later, the British Prime Minister, Herbert Henry Asquith (1852-1928) – keen to assuage American anxieties about British conduct – announced his intention to introduce home rule as swiftly as possible. As the head of the Irish police pointedly observed, Irish nationalists concluded that six days of violence had achieved more than twenty-five years of constitutional agitation at Westminster.[21]

The most important consequence of 1916 was its impact on Irish nationalism. The Rising brought the revolutionary tradition from the margins to the centre of Irish politics, reviving insurrection as a viable strategy. It enabled the rebels to assert a powerful continuity with Ireland’s past rebellions and it established the specific aim of a Republic as the common goal of advanced nationalists. In winning popular support for this unattainable objective, it sowed the seeds for the War of Independence (1919-1921) and Civil War (1922-1923). Over the longer term, the Rising’s potent legacy legitimised subsequent republican elites willing to use violence to achieve their aims.

The Easter Rising’s function as a foundation myth for the independent Irish state that emerged from the revolution has proven as important as the historical event. The political class that held power over the next five decades rooted its legitimacy within the Rising which became the preeminent symbol of Irish sovereignty. Like all iconic events, it has been subject to endless contestation and re-interpretation. Despite the radicalism of the Proclamation, intoned in an atmosphere of solemnity and pomp outside the GPO each Easter, commemoration of the Rising reinforced the conservative Catholic ethos of the state rather than the revolutionary potential of the historical event. An excessive focus on 1916 by the state and its politicians facilitated silence about the wider conflict in which 200,000 rather than 2,000 Irish combatants had fought. The last two decades, however, have witnessed a radical shift in attitudes about both the First World War and the Rising, evidenced by the warm public response when in 2011 the British monarch, Queen Elizabeth II, honoured Irishmen who fought for – and against – the Crown in both conflicts during the first British royal visit to Ireland since independence.

From the 1960s, when academic historians began to challenge the nationalist orthodoxy promoted by the state, the Rising became the subject of a bitter “revisionist” historiographical controversy. Although inevitable – all mature societies outgrow their attachment to crude myths – critical scrutiny of the actions and shortcomings of the rebels by academic historians was complicated by the outbreak of the Northern Irish Troubles in the late 1960s which ensured that debates about the morality and legitimacy of political violence in 1916 belonged to political as much as historical discourse.

The most significant historiographical (and commemorative) shift in recent decades has been a greater emphasis on understanding the Easter Rising – and the wider Irish revolution – within the context of the international experience of the Great War and its aftermath.[22] The adoption of comparative and transnational perspectives to analyse such themes as the ideological conflict between imperialism and democratic self-determination, the emergence of paramilitarism and counter-revolutionary state violence, the role of sectarian and ethnic violence and the legacy of succession, partition, and territorial loss, have opened up new perspectives by highlighting the connections and parallels between political violence in Ireland and in other multi-ethnic empires transformed by the First World War.

Fearghal McGarry, Queen’s University Belfast

Section Editor: Edward Madigan

Notes

- ↑ Although not court-martialled with the other rebels, Roger Casement (1864-1916) was subsequently tried for treason and hanged at London’s Pentonville Prison on 3 August 1916. A former British consul, Casement had travelled to Berlin in 1914 in an unsuccessful effort to win substantial German backing for a rebellion. He returned to Ireland by submarine intent on averting the insurrection but was captured on 21 April after he was put ashore at Banna Strand, County Kerry.

- ↑ Fitzpatrick, David: Militarism in Ireland, 1900-1922, in: Bartlett, Thomas and Jeffery, Keith (eds.): A military history of Ireland, Cambridge 1996, pp. 379-406.

- ↑ McGee, Owen: The IRB: The Irish Republican Brotherhood from the Land League to Sinn Fein, Dublin 2005, pp. 355-356.

- ↑ Jackson, Alvin: Ireland 1798-1998: politics and war, Oxford 1999, pp. 199-200.

- ↑ McGarry, Fearghal: Rebels. Voices from the Easter Rising, Dublin 2011, p. 130; McGarry, Fearghal: The Rising. Ireland: Easter 1916, Oxford 2010, p. 99.

- ↑ McGarry, The Rising 2010, p. 97.

- ↑ Quoted in Kelly, M.J.: The Fenian ideal and Irish nationalism, 1882-1916, Woodbridge 2006, p. 240.

- ↑ Pearse, Padraic H.: The coming revolution (1913).

- ↑ Augusteijn, Joost: Patrick Pearse: the making of a revolutionary, Basingstoke 2010; Moran, Sean Farrell: Patrick Pearse and the politics of redemption: the mind of the Easter Rising, 1916, Washington D.C. 1994.

- ↑ Connolly, James: Notes on the front. In: Workers’ Republic, 5 February 1916.

- ↑ McGarry, The Rising 2010, pp. 210-246.

- ↑ 1916 Rebellion Handbook, Dublin [1916] 1998 edition, p. 45.

- ↑ O’Halpin, Eunan: Counting Terror: Bloody Sunday and The Dead of the Irish Revolution, in Fitzpatrick, David: Terror in Ireland 1916-1923. Dublin 2012, p. 150.

- ↑ Quoted in McGarry, The Rising 2010, p. 73.

- ↑ Quoted in Townshend, Charles: Easter 1916: the Irish rebellion, London 2005, p. 189.

- ↑ Foy, Michael / Barton, Brian: The Easter Rising. Stroud 1999, p. 188.

- ↑ Rebellion Handbook, p. 23.

- ↑ Quoted in McGarry, Rebels 2011, p. 175.

- ↑ Military Archives, Dublin, Bureau of Military History Witness Statement 864 (W.E. Wylie).

- ↑ Hansard, H.C. Debates, 5th Series, vol. 82, cols 935-51.

- ↑ McGarry, The Rising 2010, p. 285.

- ↑ See, for example, Horne, John / Madigan, Edward (eds.): Towards commemoration: Ireland in war and revolution 1912-1923, Dublin 2013.

Selected Bibliography

- Augusteijn, Joost: Patrick Pearse. The making of a revolutionary, Houndmills; New York 2010: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Doerries, Reinhard R.: Prelude to the Easter Rising. Sir Roger Casement in imperial Germany, London; Portland 2000: Frank Cass.

- English, Richard: Irish freedom. The history of nationalism in Ireland, London 2007: Pan Books.

- Fanning, Ronan: Fatal path. British government and Irish revolution, 1910-1922, London 2013: Faber & Faber.

- Fitzpatrick, David: The two Irelands, 1912-1939, Oxford; New York 1998: Oxford University Press.

- Horne, John / Madigan, Edward (eds.): Towards commemoration. Ireland in war and revolution, 1912-1923, Dublin 2013: Royal Irish Academy.

- Jeffery, Keith: The GPO and the Easter Rising, Dublin; Portland 2006: Irish Academic Press.

- McGarry, Fearghal: Rebels. Voices from the Easter Rising, Dublin 2011: Penguin Ireland.

- McGarry, Fearghal: The rising. Ireland, Easter 1916, Oxford; New York 2010: Oxford University Press.

- Townshend, Charles: Easter 1916. The Irish rebellion, London 2006: Penguin.

- Wills, Clair: Dublin 1916. The siege of the GPO, London 2009: Profile.