Introduction↑

South Africa entered World War I when Britain’s ultimatum to Germany expired on 4 August 1914. The priority for the young Union was to protect its borders and realise the expansionist desires each of the Union’s constituent parts had had from before union.[1] This, together with a request from Britain to put the wireless stations in German South West Africa (GSWA) - Namibia - out of action, saw South Africans set out to subdue their neighbouring German colony. Following various delays including an Afrikaner rebellion, South Africa conquered South West Africa on 9 July 1915. The Union Defence Force (UDF) was then free to serve in other theatres if the Union Parliament consented. To prevent further political unrest, Parliament was never asked for permission, but with Britain’s approval, troops were recruited to serve in Europe and German East Africa (Tanzania) as Imperial Service Troops.[2]

Initially, in early 1915, 200 South African Imperial Service troops saw service in Nyasaland (Malawi), while the main contingent of about 10,000 men were to see service in the north of the German colony the following year. The main South African contingent arrived in Mombasa, British East Africa (Kenya) during December 1915 and fought their first battle on 12 February 1916 where they were repulsed. On 19 February, the South African Minister for War and Deputy Prime Minister General Jan Smuts (1870-1950) arrived to take command of the theatre. By the time he left in January 1917, most of the German colony was in Allied hands. During November 1916, large numbers of South Africans were repatriated home to recover from malaria, dysentery and the consequences of malnutrition. Many went on to serve in Europe and Palestine while others returned to East Africa when South African General Jaap van Deventer (1874-1922) replaced British General Reginald Hoskins (1871-1942) as Commander in Chief in July 1917. South Africans continued to serve in the theatre until the surrender of the German General Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck (1870-1964) on 25 November 1918, with many only being demobilised in February 1919 when the last German forces, including von Lettow-Vorbeck, left for Germany.

South African War Aims↑

In April 1915, as it was becoming clear that the GSWA campaign would be wrapped up, thoughts started to turn to the next theatre where South Africans could serve. On the African continent, the Germans were still fighting in Cameroon and East Africa.[3] Of the two theatres, East Africa was more alluring but it was at a stalemate following the British disaster at Tanga in November 1914 and the setback at Jasin in January 1915.[4] In South Africa, letters started to appear in the press suggesting that East Africa would be an ideal destination for the UDF as it would add additional territory to the Union and provide a place for settling evicted Belgians.[5]

By the time the campaign in GSWA ended on 9 July 1915, no decision had been made regarding East Africa as Lord Horatio Herbert Kitchener (1850-1916), Secretary of State for War in London, wanted all possible manpower for Europe. This contrasted with the British politicians who felt there would be tangible benefits from defeating German East Africa including supporting Louis Botha (1862-1919) and Smuts’s aim of uniting English and Afrikaans speakers in the Union. This would be achieved by providing an outlet for men, who would not fight in Europe for fear of political retribution back in the Union for being pro-British, to serve their country. In this they were supported by the Governor-General Sydney Buxton (1853-1934).[6]

South Africa hoped that, through its involvement in East Africa, it would realise its dream of a greater South Africa. Obtaining the Portuguese East African (Mozambique) port of Lorenzo Marques (Maputo) would reduce the cost of transporting gold to the coast from Johannesburg as the line was shorter than either the one to Cape Town or Durban, the harbour deeper than at Durban and less prone to storms than Cape Town. Manpower recruiting costs would be eased for the mines as the need to negotiate with the Portuguese government would be removed. In addition, rounding off the Union territory to the Limpopo or even the Zambezi River would help protect the Union from diseases such as rinderpest and foot-and-mouth which had almost been eradicated.[7] In exchange for Lorenzo Marques and the southern part of the Portuguese colony, Portuguese East Africa would be given an equivalent size slice of southern German East Africa.[8] Together with GSWA, the Union would, with the Portuguese territory, control the whole of southern Africa.

Recruitment↑

Recruitment for service in East Africa could not begin until Britain approved sending the force. For the main force which arrived in December 1915, permission was only given in November when the British government, excluding Lord Kitchener, agreed to re-activate the campaign in that theatre.[9]

Between June and November 1915, the South African government had to ensure that it harnessed the services of those loyal South Africans who had served in GSWA. Without guidance, many would have found their way to England to serve there while others would have returned to their civilian lives once demobilised. Therefore, word was passed around and men who were interested in further service in Africa were asked to put their names on a list. They would be notified when they were required.[10]

This future and continued use of South African troops in the war presented the South African government with a dilemma. The new Nationalist Party which had tacitly supported the Afrikaner rebellion, attacked the government in Parliament for not putting South Africa’s interests first. However, the party could not challenge supporting Britain over Germany as this could be regarded as treason, so they found economic reasons to object to the war. These featured in the October 1915 election. Prime Minister Louis Botha won the election, with no mention of the war in his election manifestoes, but with a smaller majority than he wanted. The Nationalist Party took a large share of the vote.[11] Botha therefore had to tread carefully to avoid further Nationalist Party gains.

Governor General Buxton played a pivotal role in helping the government avoid confrontation in Parliament over the war. Buxton put pressure on Britain to support South Africa by covering the cost of the troops serving in East Africa and Europe so that the Nationalist Party had no say over their service outside of the Union. According to the Union Defence Act of 1912, any South African force serving outside the borders of the Union had to be approved by Parliament. The British government agreed and so the troops raised for service in the north of German East Africa served as Imperial Service troops rather than as South Africans.[12]

In addition to those who had indicated at the end of the GSWA campaign that they would serve in East Africa, recruitment rallies were held and advertisements placed in newspapers. Men were offered free dental treatment if this was all that would prevent them passing their fitness medical.[13] However, fewer men enlisted than had been anticipated, with the result that Botha and Smuts felt they could not ask Britain for sole control of the campaign as they had had with GSWA. Furthermore, Smuts had hoped to accompany the forces to German East Africa as Commander, but the election result forced him to reconsider. General Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien (1858-1930) was appointed instead. It was only in February 1916, when Smith-Dorrien’s health would delay his arrival in East Africa by another month that Smuts was appointed Commander-in-Chief. From December 1915 to the end of the war, 30,623 white South African soldiers served in East Africa with a further 2,073 in the south of the German colony from February 1915, totalling 32,296 (2.56 percent of the Union’s white population and 0.36 percent of the total population).[14]

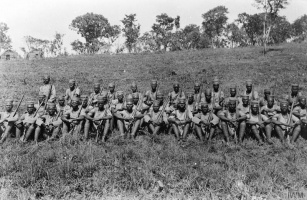

While negotiations with London were taking place over the sending of white South African troops to East Africa, other discussions were taking place between Britain and South Africa regarding the military use of other South Africans. The result was that in August 1915, it was agreed that a Cape Corps consisting of Cape Coloured (mixed race) soldiers be sent to East Africa. A second Corps was sent in 1917, making a total of 8,000 men who served in the theatre.[15] These men had been offered by the African People’s Organisation (APO) led by Dr. Abdul Abdurahman (1872-1940) who had been trying since the outbreak of war to find a patriotic outlet for this group.[16] In addition, two companies of Indian stretcher bearers, totalling 250 men, were raised for service anywhere Indian troops were serving and they too saw service in East Africa.[17] Finally, approximately 18,000 black men from across Southern Africa were to serve in the South African Native Labour Corps in East Africa.[18]

South African Forces in the Campaign↑

The first South African troops to serve in East Africa were 200 men recruited for Nyasaland to help support the protectorate after the Chilembwe uprising when approximately 200 blacks rebelled against oppressive employers between 23 January and 3 February 1915.[19] These South Africans were incorporated into the Nyasaland forces and were to eventually serve under General Edward Northey (1868-1953) who was appointed Commander of the Nyasaland-Rhodesia Field Force on 12 November 1915. By March 1917, the men of the 1st South African Infantry and 2nd South African Rifles were so unfit due to tropical disease that by July the remaining men of the contingents were divided between the King’s African Rifles (KAR) as machine gunners. The 5th South African Infantry joined the forces in March 1917 but took some time to become an effective fighting force due to the limited training they had received.[20]

The main South African contingent to serve in East Africa started arriving in December 1915 following the approval of the British War Cabinet. On 12 February 1915 the forces under General Michael Tighe (1864-1925), acting Commander-in-Chief in General Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien’s absence, launched an attack on Salaita Hill.[21] The attack on Salaita Hill was an attempt by the British to force the Germans out of the only British territory they held during the war. However, the section containing the South Africans was repelled while the Indian troops, who had fled at Tanga in November 1914, stood firm.[22] The South African General Jan Smuts arrived on 19 February to take command of the forces.

Ordered “to undertake an offensive defensive with the object of expelling the enemy from British territory and safeguarding it from further incursion,” Smuts used a strategy of manoeuvre and encirclement.[23] This called for speed and secrecy, both of which were difficult where the local population feared the Germans more than the British and the German forces were highly motivated. This did not stop Smuts. Following his arrival, the push to remove the Germans from British territory started in earnest. By 9 March 1915 the Germans had left Salaita Hill and started withdrawing towards Moshi in German East Africa. They retreated along the railway line towards Tanga and along the Pangani River as well as moving towards Handeni and onto Morogoro. Smuts, after his initial advance on Moshi, reorganised his forces, having some Indian officers replaced by South Africans. His General Staff was also largely replaced. He pushed his forces to converge on the Germans pressing southwards. Alongside the main force moving down the east of the colony, combined naval and armed forces occupied the coastal towns, while General Charles Crewe (1858-1936) worked alongside the Belgians in the west to occupy Tabora. By the time Smuts left for South Africa and London in January 1917, most of the German colony was in Allied hands although German forces remained active in the field.[24] Shortly before Smuts departed from East Africa, he had the majority of the South African forces, including the black labourers, returned to the Union to recover from the effects of campaigning in the tropical country. To replace the troops, during the latter half of 1916 the KAR was expanded while fresh troops from India arrived as well as soldiers from the Gold Coast, Nigeria and West Indies. In early 1917, when General Hoskins, Smuts’s replacement asked for reinforcements from South Africa he was told none were available. However, when General van Deventer assumed command in May 1917, reinforcements from South Africa were forthcoming, including the 2nd Cape Corps.[25] Many of the white troops served in the Transport Corps and with the KAR. The 2nd Cape Corps saw the campaign through to its conclusion.[26]

Unlike Smuts, van Deventer was under pressure to bring the campaign to an "early termination" and to limit demands for tonnage. Having been on the receiving end of poor rations, he ensured that lines of communication were maintained and troops supplied. He also chose to confront the Germans when he could, employing a strategy of attrition. However, van Deventer’s Portuguese allies were too weak to help bring the campaign to an end before the armistice was signed on 11 November 1918.[27]

Impact of the Campaign in South Africa↑

In all, the campaign in East Africa had little impact in South Africa. The troops and auxiliary services, of all racial groups, who returned to the Union beginning at the end of 1916 were not met by huge welcoming crowds as those returning from GSWA had been. This was to prevent an outcry at the number who were returning ill. Charles Lucas records that 2,361 whites and 211 Coloureds died while 1,374 whites were wounded along with ninety-nine Union Imperial Service details in East and Central Africa as well as Egypt.[28] It is not clear whether Lucas includes in his figures the 135 men of the Cape Labour Corps who died on board the Aragon which returned the men to South Africa. Their death was for the East Africa campaign as significant as the sinking of the SS Mendi was for the country as a whole.[29] 19 percent of the men on board the Aragon died: “they made up their minds to die and die they did.”[30] This led to a reluctance to enlist and Botha refusing to send more black South African labour to East Africa.

Compared with the numbers lost in Europe, the losses in East Africa were insignificant, but the reasons for the men’s return were not. In October 1916, Colonel Hedley John Kirkpatrick (1873-?) of 9th South African Infantry submitted a formal complaint against Smuts’s handling of the troops in East Africa and a court of enquiry was initiated. Smuts, who organized the enquiry, was exonerated.[31] The General Staff claimed that Smuts purposefully avoided confrontations with the Germans to prevent unnecessary deaths throughout combat while clearing the territory of the enemy. Smuts’s reputation as an army officer was tarnished.[32] Van Deventer, not being in the political spotlight, avoided any such accusations and his tenure as Commander-in-Chief all but disappeared into obscurity.

Politically, the campaign had little impact in the Union for the same reasons the Nationalists had not raised objections to the recruitment of the forces. With an election looming in 1924, neither party wanted to draw attention, positive or negative, to the Union’s contribution as it could be a potential vote loser or lead to claims of treason. The arguments, therefore, once again centered on the economy and the position of the Union within the British Empire. This was made easier by the fact that South Africa was not awarded any territory in East Africa during the peace discussions at Versailles which eliminated the possibility of a territorial swap with Portugal.[33]

Conclusion↑

Internal politics caused the memory of the campaign in East Africa to erode. Unlike Delville Wood and Square Hill in Palestine, the campaign in East Africa was not regarded as real war. There were no battles in which South Africans excelled as a unit and no leading politicians to raise the profile of the campaign or to push for a lasting memorial.[34] Consciously or otherwise, the South African government worked to reduce the memory of the campaign. Unless they remained in the armed forces, Coloureds were discouraged from wearing uniforms and medals, while black labourers were denied medals because they had been raised through labour organizations and not the military. The underlying reasons for this were varied and mainly concerned the latent “black fear” which dominated white South African thinking: it would reduce the chance of solidarity amongst veterans.

Today, few South Africans remember their country’s involvement in the East Africa campaign. This is despite the annual Comrade’s Marathon, a grueling ninety-two kilometer run between Durban and Pietermaritzburg in honor of the comrades Vic Clapham (1886-1962) lost in the East African theatre.[35]

Anne Samson, Great War in Africa Association

Section Editor: Timothy J. Stapleton

Notes

- ↑ Hyam, Ronald: The failure of South African expansion, 1908-48, London 1972.

- ↑ Samson, Anne: Britain, South Africa and the East Africa Campaign, 1914-1918. The Union Comes of Age, London 2006.

- ↑ Strachan, Hew: The First World War in Africa, London 2007.

- ↑ Paice, Edward: Tip and run. The untold tragedy of the Great War in Africa, London 2007; Anderson, Ross: The forgotten front: the East African campaign 1914-1918, London 2004.

- ↑ Citizen. Transvaal Leader, 22 April 1915.

- ↑ Samson, Britain, South Africa and the East Africa Campaign 2006.

- ↑ Hyam, Ronald: The failure of South African expansion, London 1972.

- ↑ Samson, Britain, South Africa and the East Africa Campaign 2006.

- ↑ Kitchener had purposefully been sent to the Dardanelles to advise on the evacuation of the troops from that theatre. See Samson, Anne: World War 1 in Africa. The forgotten conflict of the European powers, London 2013.

- ↑ Samson, Anne: South Africa and the First World War, in: Paddock, Troy R.E. (ed): World War 1 and Propaganda, Leiden 2014.

- ↑ Samson, Britain, South Africa and the East Africa campaign 2006.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Samson, South Africa and the First World War 2014.

- ↑ Lucas, Charles: The Empire at War, vol. 5. London 1921; population in 1911 (census): total population 8,973,394; white population 1,276,242.

- ↑ Perkins, A Eames: Recruitment of the Cape Corps. In: Difford, Ivor: The Story of the 1st Battalion Cape Corps (1915-1919). Cape Town 1920, p. 26; Winegard, Timothy C: Indigenous Peoples of the British Dominions and the First World War. Cambridge 2011.

- ↑ Samson, Britain, South Africa and the East Africa Campaign 2006; Grundy, K.W.: Soldiers without politics: Blacks in the South African armed forces, California 1983; Grundlingh, A.: Fighting their own war: South African blacks and the First World War, Johannesburg 1987.

- ↑ Vahed, Goolam: ‘Give Till it Hurts’: Durban’s Indians and the First World War, in: Journal of Natal and Zulu History 19/1 (2011), pp. 41-60.

- ↑ Willan, B.P.: The South African Native Labour Contingent, 1916-1918. In Journal of African History 19/1 (1978), pp. 61-86; Lucas, The Empire at War 1921.

- ↑ Phiri, D.D.: Let us die for Africa. An African perspective on the life and death of John Chilembwe of Nyasaland/Malawi, Blantyre 1999; Shepperson, George: Independent African. John Chilembwe and the Nyasaland Rising of 1915, Kachere 2000.

- ↑ McCracken, John: A History of Malawi, 1859-1966, Woodbridge 2012.

- ↑ Samson, Britain South Africa and the East Africa Campaign 2006.

- ↑ Paice, Tip and run 2007; Anderson, The forgotten front 2004.

- ↑ Anderson, Ross: JC Smuts and JL van Deventer. South African Commanders-in-Chief of a British Expeditionary Force, in: Scientia Militaria 31/2 (2003), pp. 116-141.

- ↑ Paice, Tip and run 2007; Anderson, The forgotten front 2004.

- ↑ Paice, Tip and run 2007; Anderson, The forgotten front 2004; Samson World War 1 in Africa 2013.

- ↑ Desmore, A.J.B.: With the 2nd Cape Corps thro' Central Africa, Cape Town 1920.

- ↑ Anderson, JC Smuts and JL van Deventer 2003; Nasson, Bill: Springboks on the Somme. Rosebank 2007.

- ↑ Lucas, The Empire at War 1921.

- ↑ Clothier, Norman: Black Valour: The South African Native Labour Contingent 1916-1918 and the Sinking of the Mendi, London 1998, p.1. A total of 625 lives were lost, including ten whites. Grundlingh, Albert: Mutating Memories and the Making of a Myth: Remembering The SS Mendi Disaster, 1917–2007, in: South African Historical Journal 63/1 (2011), pp. 20-37.

- ↑ The National Archives (Kew): CAB 45/44, Fendall diary, 1 Jun 1917, f.76.

- ↑ South African Herald, 2 Feb 1918, report 18 Jan 1918, 26 Jan 1918.

- ↑ Anderson, JC Smuts and JL van Deventer 2003.

- ↑ Samson, Britain, South Africa and the East Africa Campaign 2006.

- ↑ The push for a memorial at Delville Wood was spearheaded by the South African politician Percy Fitzpatrick (1862-1931) who lost a son on the Western Front. Smuts approved the memorial in Europe so long as it was done through private subscription. Fitzpatrick’s son who fought in East Africa survived the campaign. Samson, Britain, South Africa and the East Africa Campaign 2006.

- ↑ Comrades Marathon Association, 1920-1925: A soldier's dream, issued by Comrades Marathon Association, online: http://comrades.com/home-about/history-of-comrades, (Retrieved 10 December 2013).

Selected Bibliography

- Adler, F. B. / Lorch, A. E. / Curson, H. H.: The South African Field Artillery in German East Africa and Palestine, 1915-1919, Pretoria 1958: J. L. Van Schaik.

- Bisset, W. M.: Unexplored aspects of South Africa's First World War history, in: Militaria 6/3, 1976, pp. 55-61.

- Brown, James Ambrose: They fought for king and kaiser. South Africans in German East Africa, 1916, Johannesburg 1991: Ashanti Pub.

- Clothier, Norman: Black valour. The South African Native Labour Contingent, 1916-1918, and the sinking of the Mendi, Pietermaritzburg 1987: University of Natal Press.

- Collyer, John Johnston: The South Africans with General Smuts in German East Africa, 1916, Pretoria 1939: Government Printer.

- Grundlingh, Albert M.: Fighting their own war. South African Blacks and the First World War, Johannesburg 1987: Ravan Press.

- Grundlingh, Albert M.: War and society. Participation and remembrance. South African Black and Coloured troops in the First World War, 1914-1918, Stellenbosch 2014: SUN Media.

- Hordern, Charles / Stacke, H. Fitz M.: Military operations East Africa, August 1914-September 1916, volume 1, Nashville; London 1941: His Majesty’s Stationery Office.

- Katzenellenbogen, Simon E.: Southern Africa and the war of 1914-1918, in: Foot, Michael Richard Daniell (ed.): War and society. Historical essays in honor and memory of J. R. Western, 1928-1971, London 1973: Paul Elek, pp. 107-121.

- Maker, J. G.: A narrative of the Right Section, 5th Mountain Battery, South African Mounted Riflemen, Central African Imperial Service Contingent, Nyasaland, 1915-1918, part 1, in: Military History Journal 4/1, 1977, pp. 30-33.

- Maker, J. G.: A narrative of the Right Section, 5th Mountain Battery, South African Mounted Riflemen, Central African Imperial Service Contingent, Nyasaland, 1915-1918, part 2, in: Military History Journal 4/2, 1977, pp. 39-53.

- Nasson, Bill: Springboks on the Somme. South Africa in the Great War, 1914-1918, Johannesburg; New York 2007: Penguin.

- Samson, Anne: World War I in Africa. The forgotten conflict among the European powers, London; New York 2013: I. B. Tauris.

- Samson, Anne: Britain, South Africa and the East Africa campaign, 1914-1918. The union comes of age, London; New York 2006: I. B. Tauris; St. Martins Press.