Introduction↑

Admiral Sir John Rushworth, 1st Earl Jellicoe (1859–1935) entered the Royal Navy in 1874 and specialized in gunnery, working with Admiral Lord John Fisher (1841-1920), and notably helping design Fisher’s Dreadnought. In 1912, Fisher persuaded Winston Churchill (1874-1965) to organize the forthcoming appointments so that Jellicoe would command the Grand Fleet in 1914. Fisher and Jellicoe believed that mines, submarines and Zeppelins meant the North Sea was no place for dreadnoughts.

On 4 August 1914, Jellicoe became commander-in-chief of the Grand Fleet at Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands, with his flagship being the HMS Iron Duke. His mission was the economic blockade of Germany. To break the blockade, Germany would have to seek battle with an inferior fleet off the north coast of Scotland. Natural caution, allied with years of conditioning, made Jellicoe an arch centralizer, his “Grand Fleet battle orders”, restricted the initiative of his subordinates. He maintained the morale of the fleet through sports, entertainment and humane leadership.

Battle of Jutland↑

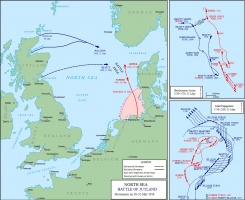

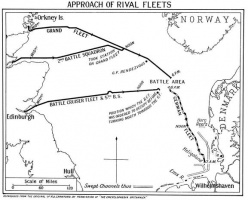

In May 1916, Admiral Reinhard Scheer (1863-1928) planned to draw Jellicoe over a submarine ambush, and then engage part of his fleet. British naval intelligence ensured Jellicoe put to sea before Scheer, to rendezvous with Admiral Sir David Beatty’s (1871-1936) battlecruisers off the Jutland peninsula on the afternoon of 31 May. In the battle cruiser action, Admiral Franz von Hipper's (1863-1932) five ships sank two of Beatty's six. Beatty sighted Scheer's battlefleet, which he led towards Jellicoe, who deployed his six columns of battleships into a single line ahead. This manoeuver secured the best light conditions for gunnery, put his fleet between Scheer and his bases, and performed a classic “crossing the T” maneuver. The British inflicted serious damage on the leading German battleships, forcing Scheer to order an emergency “battle turn away” on two occasions, retreating into the haze of fog, coal smoke and cordite fumes, and covering his retreat with a mass torpedo attack. Jellicoe made no effort to regain contact at night, planning to resume the battle at daybreak. However, Scheer escaped through the rear of the British fleet that night, with Jellicoe left in the dark by his subordinates.

Securing British Commercial Shipping↑

Jutland confirmed British command of the sea. Having failed to secure victory on land, the German high command adopted unrestricted submarine warfare against commerce, hoping to sink enough shipping to starve Britain into defeat in six months, before American intervention could take effect. Jellicoe was appointed first sea lord on 4 December 1916, in order to meet this threat. Unrestricted submarine warfare began on 1 February 1917.

Jellicoe created an anti-submarine division of the staff, adding a trade division to naval intelligence, and integrated shipping, ports, inland transport and import priorities into overall policy. Ultimately the convoy system proved decisive, denying the U-boats easy targets. Jellicoe lacked the social contacts, outgoing personality, and political acumen to be a great first sea lord; his characteristic pessimism annoyed Prime Minister David Lloyd George (1863-1945). Exhausted and ill, Jellicoe was sacked on Christmas Eve 1917. His work led to the defeat of the U-boats in 1918. Viscount Jellicoe of Scapa died on 19 November 1935; he was buried in St Paul's Cathedral, close to Horatio Nelson, Lord Nelson (1758-1805).

Andrew Lamberg, King's College London

Section Editor: Jennifer Wellington

Selected Bibliography

- Bacon, Reginald: The life of John Rushworth, Earl Jellicoe, London 1936: Cassell.

- Goldrick, James: The king's ships were at sea. The war in the North Sea, August 1914-February 1915, Annapolis 1984: Naval Institute Press.

- Gordon, G. A. H.: The rules of the game. Jutland and British Naval Command, London 2005: John Murray.

- Marder, Arthur Jacob: From the dreadnought to Scapa Flow. The war years. To the eve of Jutland, 1914-1916, volume 2, Anapolis 2013: Naval Institute Press.

- Patterson, A. Temple: Jellicoe. A biography, London; New York 1969: Macmillan; St. Martin's Press.