Introduction: Opening Moves (July 1914-March 1915)↑

At the beginning of the war, Germany, Austria-Hungary, and the Triple Entente nations had diplomatic and consular outposts, commercial interests, and expatriate communities scattered throughout the Americas. In addition, small Japanese settlements dotted the map from the Rio Grande to the River Plate, and mariners and adventurers from North America were ubiquitous.

The opening moves of the intelligence war in Latin America began weeks before the major powers mobilized. Nine days after the Sarajevo assassination, the German ambassador to the United States, Johann Heinrich Count von Bernstorff (1862-1939), was put in charge of espionage, sabotage, propaganda, and arms purchases in the Americas. He and his staff quickly established and coordinated active intelligence outposts from Ciudad Juarez in Mexico to Punta Arenas, Chile.

Germany had anticipated the demands of a war between European empires when it laid out a worldwide intelligence and logistics network—the Etappendienst der Marine —during the century’s first decade. At the command of the Admiralstab, a legion of dormant Etappendienst agents was mobilized to fulfill a variety of covert naval support roles: relaying German communications, intercepting Entente communications, stocking colliers to resupply warships, facilitating the passage of reservists to their duty stations, and other tasks. Civilian vessels were quickly and covertly adapted to wartime functions as of August 1914, and by October, German marauders prowled trade routes linking the Americas with the rest of the world. Any ship flying an Allied flag or carrying Allied cargo was a target. Germany’s first naval success came on 1 November 1914, when Maximilian Reichsgraf von Spee (1861-1917) sank British cruisers HMS Good Hope and Monmouth forty miles west of Coronel, Chile. Von Spee’s flagship, along with three other cruisers, was sunk a month later by British ships in the Falklands, dooming German naval efforts in the South Atlantic.

Sabotage and Economic Warfare (March 1915-April 1917)↑

In 1915, Germany turned its attention to disrupting the Allies’ trans-Atlantic supply lines. German intelligence was tasked with sabotaging defense industries in the US, inciting war between Mexico and the US, and disrupting maritime commerce with Europe. Secret diplomacy and propaganda aimed to influence the American republics to remain neutral and adopt pro-German policies.

Fomenting war between Mexico and the US promised to divert American arms and attention away from Europe. Mexican-US relations were already volatile in the wake of the seven-month US occupation of Veracruz that ended in November 1914. When Mexico sank into a bloody free-for-all between revolutionary factions in early 1915, German agents courted them all with offerings of guns, money, and expertise.[1]

First Chief José Venustiano Carranza Garza (1859-1920), leader of the revolutionary Constitutionalist Army and Mexico’s head of state, was steering the country on a pro-German course even before relations between Carranza and US President Woodrow Wilson (1856-1924) soured in the spring of 1916. Earlier that year, Carranza had accepted a secret offer for thirty-two German officers to be seconded to his service. By summer 1916, German military and intelligence advisors were dispersed throughout Mexico.[2]

In late 1916, Carranza’s ambassador in Berlin secretly proposed a pact to German foreign secretary Arthur Zimmermann (1864-1940) that would modernize the Mexican Army with German weapons and instructors, expand the Mexican Navy, and construct munitions factories and a radio communications station to link the two capitals. Meanwhile, German agents in Mexico scouted facilities to support U-boats. US intelligence discovered German officers in Baja California, Guaymas, Sinaloa, and Tepic, and widespread cooperation between Germans and Japanese agents. In Manzanillo in February 1917, a US agent photographed the unloading of guns, ammunition, machinery, and uniforms from the Japanese ship SS Kotiharu Maru.[3]

Japan’s secret activities in Mexico came as little surprise to US intelligence, but Japanese connivance with Germany worried the Allies. If Japan could be enticed to shift her allegiance to the Central Powers, Russia would be compelled to withdraw forces from Europe’s Eastern Front and rush them to block a Japanese invasion from Manchuria, with catastrophic results for the British, French, and Belgian armies on the Western Front. As a result, Japan’s friendship was a strategic prize and the object of special operations by intelligence officers and diplomats in Mexico, Chile, and Argentina.

US Entry and Pan-American Polarization (April 1917-November 1918)↑

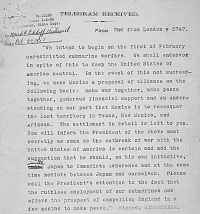

Secret diplomacy between Mexico, Germany, and Japan set the stage for one of the greatest intelligence feats of the war: the revelation of the Zimmermann Telegram. Dated January 19, 1917, the telegram carried instructions to propose an alliance between Mexico, Japan, and Germany if Berlin’s resumption of aggressive submarine warfare pushed the US to war. Intercepted by British intelligence and leaked to the press, the Zimmermann telegram infuriated Americans, and the US declared war on Germany on April 6, 1917.

Most German intelligence operatives in the US fled to Latin America as 1917 wore on. In Mexico, the roster of German intelligence officers and agents swelled, but they accomplished little of strategic value. Behind facades of neutrality, Argentina, Chile, and Venezuela turned a blind eye to prominent German intelligence organizations. To circumvent Allied sanctions, the networks engineered smuggling rackets to supply Germany through European neutrals. Sabotage against merchant ships continued, evidenced by mysterious fires and explosions aboard vessels departing South American ports. Agents and couriers for covert missions into Allied countries were recruited in Santiago, Caracas, and especially Buenos Aires. Agents of influence infiltrated governments and German agents penetrated US legations in Buenos Aires, Lima, Rio de Janeiro, La Paz, and Caracas. Meanwhile, generous subsidies inspired sympathizers, writers-for-hire, and publicists to maintain the drumbeat of propaganda to sway Latin American public opinion toward neutrality.

A few countries became steadfast Allies—Cuba, Panama, Peru, Uruguay, and Brazil. Their governments cooperated with Allied counterintelligence efforts to root out German spy networks. German intelligence had capitalized on Cuba’s strategic location in the shadow of the US and as a crossroads for Caribbean shipping. A concerted effort by Cuban secret police, Allied intelligence, and the US War Trade Board disrupted German espionage, courier and contraband networks in April 1918. The anti-German campaign ruined the Uppmann family’s cigar-making and banking empires and strengthened Cuban intelligence as a domestic political weapon. Panama’s defenses were bolstered by US army aviation and Puerto Rican infantry units to protect the Panama Canal. Brazil stood at the forefront of the Allied cause in Latin America, yet a German intelligence clique in Rio de Janeiro was suspected in one of the most perplexing tragedies in US Navy history, the sinking of the USS Cyclops, a huge supply ship that vanished with 300 passengers.[4] In Peru, German agents sabotaged interned ships, paid agitators to incite strikes and destructive riots, and reinforced Chilean espionage in preparation for military invasion. To humiliate Uruguay, Berlin dispatched submarine U-157 to stop a Spanish liner in mid-Atlantic, remove the Uruguayan Military Mission, and force them to choose between execution or renouncing their pro-Allied mission.

Conclusion↑

The intelligence war did not have a clean-cut ending. Berlin slowed down foreign intelligence operations weeks before the Armistice, but did not order overseas missions to start burning documents until two months later. By that time, Japanese intelligence had hired many of the principal German intelligence officers in South America, and US and British agents were competing against each other for Central American oil concessions. When an outbreak of strikes, riots, and political violence shook Argentina in early January 1919, German agents and banks funded and organized actions that targeted Allied commercial establishments. Most German intelligence officers aligned themselves with a secret intelligence directorate run by militarists in the War Ministry in post-war Berlin. In the last 17 months of the war, the US had expanded the Allied economic war against German enterprises in Latin America, capitalizing on the opportunity to grab market share in the name of liberty, even eagerly filling the vacuum left by receding wartime British commerce. Despite the best efforts of German intelligence, the US became the dominant force in Latin American trade. The US demobilized most foreign intelligence personnel in Latin America in early 1919, but the US delegation to the Paris peace talks included an intelligence analysis group. Indeed, preparations for the next world war had begun before the first one was finished.

Jamie Bisher, Independent Scholar

Section Editor: Stefan Rinke

Notes

- ↑ von der Goltz, Horst: My Adventures as a German Secret Agent, New York 1917, pp. 254-255.

- ↑ Chalkley, John F.: Zach Lamar Cobb: El Paso Collector of Customs and Intelligence during the Mexican Revolution, 1913–1918, El Paso 1998, pp. 55-57.

- ↑ Bisher, Jamie: The Intelligence War in Latin America, 1914-1922, Jefferson, North Carolina 2015, pp. 93-95.

- ↑ War Ghosts, in: Time Magazine Vol. XVI, No. 2 (1930).

Selected Bibliography

- Bisher, Jamie: The intelligence war in Latin America, 1914-1922, Jefferson 2016: McFarland & Company.

- Chalkley, John F.: Zach Lamar Cobb. El Paso collector of customs and intelligence during the Mexican Revolution, 1913-1918, El Paso 1998: Texas Western Press.

- Goltz, Horst von der: My adventures as a German secret agent, New York 1917: McBride.

- Katz, Friedrich: The secret war in Mexico. Europe, the United States, and the Mexican Revolution, Chicago 1981: University of Chicago Press.

- Martin, Percy Alvin: Latin America and the war, Baltimore 1925: Johns Hopkins Press.