Introduction↑

Military operations in East Central Europe lasted much longer than on the Western Front. From a regional perspective, the First World War should be treated together with the fighting against the Bolsheviks, which did not end until 1921. This article will focus on the military activity of the predominantly voluntary units, which were formed from representatives of national groups in East Central Europe, with the agreement and help of Russia, Austria-Hungary and Germany. These units used no special strategies, tactics or weapons. Only their military ranks and uniform details, such as designs, collars, lapels and caps, served to distinguish them from regular troops. Generally, they did not possess weapons, such as heavy artillery or tanks, at least in sufficient numbers. The military saturation of the Eastern Front was generally lower than in the west, which resulted in a frequent shifting of the frontline over vast distances. At the same time, the troops who were left behind the frontline conducted guerrilla-type warfare, especially during the last phase of the conflict.

Warfare↑

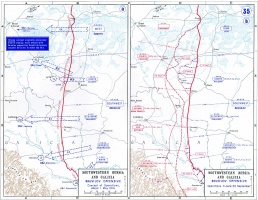

Although both the Russian and German armies had expected to gain ground even faster, the Eastern Front was nonetheless characterized by relatively rapid mobility.[1] Russian military planning aimed to fully mobilize the economy in the empire’s western periphery in order to protect the inner regions from the war’s economic repercussions. Measures included large-scale requisitions and an evacuation policy.[2]

A network of fortresses, organized in three lines, was at the core of defensive military planning. However, the German army captured them without fighting or after comparatively short sieges. The largest and most modern of these fortresses were located in the vicinities in or around Warsaw (taken on 4 August 1914), Modlin (5 August 1914), Kovno (7-15 August 1914) and Brest (15 August 1914). Cavalry remained more important on the Eastern Front than in the west. The Battle of Gumbinnen (20 August 1914) and particularly the Battle of Tannenberg (23-30 August 1914) were marked by rapid movements and surprise elements. In late 1915, however, as the front stabilized in the Baltics along the River Dvina (Daugava), mobile operations were supplanted by trench warfare. In 1916, Russian General Aleksei Brusilov (1853-1926) successfully employed the strategy of attacking small but vital points in the German and Austro-Hungarians positions. The Brusilov Offensive in turn inspired German General Oskar von Hutier (1857-1934) in his successful attack on Riga on 3 September 1917, an operation which broke the stalemate on the Eastern Front. These surprise or shock tactics were later used with success at the Western Front, as well.

In 1915, German airships began to conduct several bombing raids on strategic industrial cities, railway centres and towns behind the Eastern Front.[3] The German army first employed poison gas in Bolimów near Łódź on 31 January 1915. Artillery shelling, the burning of whole villages (by both the German and the retreating Russian armies) and short-distance urban warfare led to high levels of destruction and suffering among the civilian population. Most importantly, however, evacuation policies led to a massive uprooting of civilians, especially Jews. This significantly altered the demographics of Poland and the Baltics in the long term, as the Russian military forced large numbers of people, suspected of sympathizing with the enemy, to retreat along with the army towards the Russian interior.

Polish Voluntary Units Siding with the Central Powers↑

From the regional perspective of East Central Europe, nationally-based voluntary units, such as the Polish units that fought alongside Russia, Austria-Hungary and Germany played a relatively big role in the war.[4] Polish national circles started to organize Polish national military units early on during the war. The core of these units fighting with the Central Powers comprised Polish paramilitary organisations, which existed in Galicia prior to 1914. In early August 1914, activists under the leadership of Józef Piłsudski (1867-1935) formed the First Company with approximately 150 men. On 6 August 1914, they crossed the border between Austria-Hungary and Russian Poland with the aim of instigating an (ultimately unsuccessful) anti-Russian uprising.

Nonetheless, the Austro-Hungarian High Command decided to form, equip and support the voluntary Polish Legions (Legiony Polskie). Commencing in late 1914 with only a few hundred men, the legions reached their maximum strength of approximately 30,000 men in mid-1916. They were organized into three brigades, the first of which was commanded by Piłsudski. This unit fought in the southern and eastern regions of Russian Poland and subsequently, after the Central Powers’ offensive in 1915, in Volhynia. In June 1916, it managed to slow the speed of the Brusilov Offensive. During the Carpathian winter of 1914/15, the 2nd Brigade helped to defend Hungary against the Russian invasion. Subsequently it was sent to Bukovina and Volhynia.[5] The 3rd Brigade, formed in May 1915, fought in the region of Lublin, after which it was concentrated in Volhynia. Soldiers from these formations came predominantly from Galicia and Russian Poland. In the first months of the conflict, many members of Galician paramilitary units hastened to enlist. Different social strata were represented in the legions, with an overrepresentation of intelligentsia and under-representation of the peasantry, at least in the first months of the recruitment process. Motives for enlistment ranged from ideological (willingness to fight for Polish independence) to more mundane (avoiding conscription in the regular Austro-Hungarian army, escape from hunger, poverty, unemployment, and compulsory labour). In the second half of the war, the financial benefits for one’s family played a significant role in the decision-making process concerning enlistment in the legions.[6]

In occupied Russian Poland, after the 5 November 1916 Act, which re-established the Kingdom of Poland under the Central Powers’ control, Germans tried to form the Polish Military Force (Polskie Siły Zbrojne, in German, Polnische Wehrmacht) as the state’s military arm, under the formal command of Warsaw Military Governor Hans von Beseler (1850-1921). The Central Powers decided to integrate the Polish Legions into the Polish Military Force and subordinated them to German command. In mid-1917, however, most legionaries refused to swear a new oath of loyalty to the German emperor, demanding more political concessions to the Polish cause. As a result of this conflict, the Polish Legions were disarmed and liquidated. Their soldiers were either interned or conscripted into the Austro-Hungarian army. Only the soldiers of the 2nd Brigade under Józef Haller (1873-1960) continued to fight as the Polish Auxiliary Corps (Polnisches Hilfskorps) on the Central Powers’ side. Following the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, which Polish political activists regarded as a betrayal of their cause, soldiers of the Polish Auxiliary Corps decided to cross the frontline to join the Polish formations that had started to emerge in Russia in spring 1917. This constituted the final act of Polish Legions on behalf of the Central Powers.

Recruitment to the Polish Military Force continued in occupied Russian Poland despite the dissolution of the Polish Legions. Service in this unit, which was not sent to the front, but remained in garrison and training centres, was not especially popular among Poles, many of whom felt they were required to fight for a cause that was not their own. In October 1918 this unit numbered only about 5,000 officers and soldiers.[7]

In the first weeks of the war in Russian Poland, the secret Polish Military Organization (Polska Organizacja Wojskowa) was established, grouping together the followers of Piłsudski and those remaining under his personal control. In the first stage of its existence, the group concentrated on intelligence activity against the Russian army. After the Central Powers seized Russian Poland, the group helped to recruit and train new soldiers for the Polish Legions. In summer 1917, as a result both of the dissolution of the Legions and political repressions, it went underground. One year later, in October and November 1918, its members took part in disarming German and Austro-Hungarian soldiers. Here too, as in the case of the Polish Legions, middle-class youth – school pupils, students, scouts, and members of pre-1914 paramilitary units – played a big part. In November 1916, for example, 36 percent of the members of the Polish Military Organization came from the peasantry and 21 percent from the intelligentsia. Many of its leaders were deployed to it from the I Brigade of the Polish legions [8]

Polish Voluntary Units Siding with the Entente↑

The history of Polish voluntary units in Russia goes back to autumn 1914, when, after lengthy attempts by Polish national circles, Russian military authorities allowed such a unit (later called the Legion Puławski) to form under the auspices of the National Polish Committee in Warsaw. But this small formation, which numbered a few hundred soldiers, was almost annihilated in mid-1915 after extremely heavy fighting.

Nevertheless, due to the efforts of Polish officers in the Russian army, the Polish Riflemen Brigade, consisting of the remaining soldiers of the Legion Puławski, was established and sent to the front in early 1916. General Brusilov helped reorganize the Brigade into the Polish Riflemen Division in early 1917.

After the February 1917 Revolution in Russia, the Provisional Government was more favourably inclined toward Polish national aspirations, including national military units that could be used against the Germans. Taking advantage of this opportunity, in June 1917, a congress comprising the delegates of the committees formed by Polish soldiers and officers in the Russian army declared the establishment of a Polish national army in Russia, to be organised into three corps.

However, the general disarray in which Russia and its military found itself, combined with the October 1917 Revolution and the ensuing civil war, made it impossible for the Polish national army in Russia to become a fully-formed fighting force. The Bolsheviks regarded the Polish formations as counter-revolutionary. After the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, in which formal peace between Soviet Russia and the Central Powers was signed, most of these units decided to subordinate themselves to the Regency Council in Warsaw, still occupied by the Germans. But the Central Powers, whose troops were advancing deeper into Russian territories, disarmed and dissolved Polish units in May and June 1918. Their soldiers were later transported to the occupied Kingdom of Poland.[9]

This did not mean the dissolution of all Polish national units in Russia. The Poles and the White Guards reached an agreement whereby new Polish units were formed in Russia on territories controlled by the Whites. They were formed in the expectation that they would join the anti-Bolshevik forces, although their primary motivation was more likely a return home.

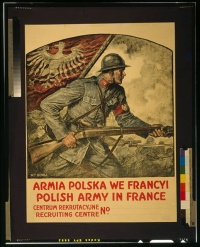

After the fall of the monarchy in Russia in February 1917, France started to form Polish units that would fight on her side and thereby giving her influence in the Polish cause after the war. In June 1917, French President Raymond Poincaré (1860-1934) issued a decree establishing a Polish army in France. The so-called “Blue Army” was formed from Polish prisoners of war (POWs) from the German army, Polish volunteers living in America, France and Holland, and Polish soldiers serving in the French army and the Russian Corps in France and Greece.

The Blue Army was not sent to the front until mid-October 1918 and barely took part in the fighting. Its significance was political rather than military. In April 1919, it numbered 60,000 officers and soldiers. After the formal cessation of hostilities on the Western Front and a long negotiation with the authorities of German Republic, these troops returned to Poland by rail in spring 1919 in time to take part in the battles with the Ukrainians over East Galicia.[10]

National Units and the Formation of New National Armies in the Baltics and Finland↑

Due to the Tsarist policy of employing soldiers in regions far from their home, relatively few local peasants fought in the Baltics; however, many were included in units of the national guard and thus employed close to their homes. Moreover, many soldiers drafted in the Vilna Military District served in the Russian 1st Army and thus fought in East Prussia.

In July 1915, the Russian High Command formed Latvian national regiments (“Riflemen” – Strēlnieki), which successfully defended the front along the River Daugava, but suffered immense losses.[11] Estonian units were formed only after the February Revolution in April 1917 and were restricted to a single regiment of 8,000 men.[12] No Lithuanian units were formed. From Finland, nearly 2,000 volunteers went to Germany in 1914 to receive military training and formed the so-called “Jäger-Battalion”. This led to a halt of conscription in Finland due to doubts regarding Finnish loyalty.[13] However, a significant number of Finns who had already been soldiers before the war, as well as numerous volunteers fought in the ranks of the Russian army.[14]

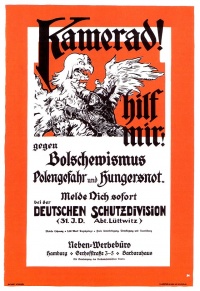

The November 1918 armistice stipulated that German troops stay in the Baltic region to defend it against Bolshevik troops. The German army, however, was in a state of dissolution, as the High Command and soldier councils struggled for power. In the beginning of December 1918, the High Command thus decided to recruit volunteers to form the so-called Freikorps (free corps), who were to assist the newly forming national armies, but instead frequently entered into conflict with them.

Already on 11 November 1918, the High Command of the German 8th Army had approved the formation of the Baltische Landeswehr (Baltic Land Defence) through the Regency Council of the pseudo-state United Baltic Duchy (Vereinigtes Deutsches Herzogtum), which was made up mainly of Baltic Germans and Russians and fought mainly in Latvia. Other notable Freikorps were the Eiserne Division (Iron Division)[15] and the Deutsche Legion (German Legion), both of which joined the Russian Western Volunteer Army in early autumn 1919. The Freikorps were under the supreme command of General Rüdiger von der Goltz (1865-1946) and numbered between 20,000 and 40,000 soldiers.[16]

The process of forming national armies, which started at the end of 1918, differed considerably from place to place. The strongest units made up of ethnic Latvians – the Riflemen, numbering 24,000 soldiers in autumn 1918[17] and quickly occupying most of Latvia in December 1918 – remained loyal to the Bolsheviks. An opposing Latvian national army (Latvijas Bruņotie spēki) was only founded in July 1919 with substantial help by the Estonians, Germans and the Entente. As the Russian army had not included any units made up of ethnic Lithuanians during World War I, a Lithuanian army (Lietuvos kariuomenė) of 10,000 soldiers only came into being in May 1919 after systematic conscription and the promise of land. Moreover, the arming of the Lithuanian Military was initially severely obstructed by the German army.[18] The Estonian People’s Army (Eesti Rahvavägi) could draw from small national units which had been formed after the February Revolution and quickly grew from 4,800 soldiers in the beginning of 1919 to 74,500 in May 1919.[19] Due to its initially small size, it had to rely on the formation of the Baltenregiment (Baltic Regiment), which was formed after negotiations between Konstantin Päts (1874-1956) and representatives of the Baltic German organizations, but remained subordinate to the Estonian Supreme Commander, Johan Laidoner (1884-1953).[20] It numbered between 700 and 800 soldiers.[21] Already in December 1918, the Estonian army had received rifles, machine guns and field guns from the British navy[22] and even employed armoured trains at the Battle of Cēsis (1919) with great effect.

The Finnish White Guard (Sojeluskunta), formed during the Revolution by Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim (1867-1951), benefitted immensely from the inclusion of the 2,000 Jäger-Battalion soldiers and formed the core of the Finnish army. The Sojeluskunta received significant support from the 10,000-strong German Baltic Sea Division under the command of Rüdiger von der Goltz. Both the anti-Communist forces and the Bolshevik forces in Finland thus numbered 50,000 to 90,000 soldiers each.[23] Officers of these newly formed armies were mostly of imperial background, for example the Lithuanians Povilas Plechavičius (1890-1973), who organized partisans in northern Lithuania, and Silvestras Žukauskas (1860-1937), the Latvian Oskars Kalpaks (1882-1919), the Estonian Ernst Põdder (1879-1932), and the Finns Johan Laidoner, Carl Mannerheim and Karl Fredrik Wilkama (1876-1947). Large parts of the rank and file were recruited from the local peasantry and had no military experience.

Apart from the Red Army, the Army of Soviet Latvia, formed in January 1919 from the Latvian Riflemen and the International Division, was the most important Bolshevik military organization in the region and managed to occupy most of Latvia by the end of 1918. A Bolshevik army of Estonian Riflemen (Eestimaa Punaarmee) was also active in Estonia before it was moved to Ukraine. It numbered up to 5,000 men and was subsequently formed into the Estonian Red Army.[24] The short-lived Lithuanian-Belorussian Soviet Socialist Republic (LitBel), however, did not command its own military and thus had to rely on the help of the Red Army.[25]

A large number of locals were included into the White Armies: the North-West Army (up to 17,000 men), which was mainly active in Estonia and northern Russia, and the West-Russian Volunteer Army (maximum 40,000 soldiers), active in Latvia and Lithuania.[26] The politics and coalitions of both were strongly determined by their respective commanders Nikolay Yudenich (1862-1933), who took the command in June 1919 from commander-to-be of the Estonian army, Johan Laidoner, and Pavel Bermondt-Avalov (1877-1974).

The defeat of the Baltische Landeswehr and Eiserne Division by joint Estonian and Latvian troops at the Battle of Cēsis (19 to 23 June 1919) initiated the retreat of the Freikorps from the Baltics. Bermondt-Avalov’s North-West Army became a holding centre for the majority of Freikorps members who did not want to return to Germany and for former Russian POWs. Its defeat by the hands of Latvian and Lithuanian forces stabilized the territorial control of national armies in Estonia and Latvia, while parts of Lithuania remained a combat zone until the end of the Polish-Soviet War in 1921.

Conclusion↑

Warfare in East Central Europe was characterized by comparatively quick movements over vast spaces. The front was significantly longer than in the west. The Russian Revolution as well as ethnic conflicts in the imperial periphery led to a series of shifting alliances. After the November 1918 armistice, the emerging Polish, Estonian, Latvian, and Lithuanian states undertook the task of creating national armies, mainly to defend themselves against the approaching Bolshevik troops, but in some cases also against each other. While the Polish military command faced the challenge of having to integrate very different types of Polish units created during the First World War, such as the Polish Legions or the Entente’s Blue Army, the Baltic states could rely on national units only to a lesser degree (and in Lithuania not at all). The mobilization of troops was significantly obstructed by both German troops and counter-revolutionary Russian White Guards, who remained stationed in the Baltics to fight Bolshevik troops.

The armies of the new states in East Central Europe, which began forming at the end of 1918, emerged from national voluntary units (mentioned above), former officers and soldiers of imperial armies, and brand new conscripts. This turned out to be a highly complicated task. For years afterwards, animosities between soldiers of different backgrounds and military experience from the Great War continued to bedevil the new national armies.[27]

Klaus Richter, University of Birmingham

Piotr Szlanta, University of Warsaw

Section Editors: Ruth Leiserowitz; Theodore Weeks

Notes

- ↑ Liulevicius, Vejas Gabriel: War Land on the Eastern Front. Culture, National Identity, and German Occupation in World War I, Cambridge 2000, pp. 12-53.

- ↑ Hatlie, Mark R.: Riga und der Erste Weltkrieg. Eine Exkursion, in: Tauber, Joachim (ed.): Über den Weltkrieg hinaus. Kriegserfahrungen in Ostmitteleuropa 1914-1921, Lüneburg 2009, pp. 13-33, 16.

- ↑ Cf. for the examples of Vilnius, Dvinsk and Šiauliai: Weeks, Theodore S.: Vilnius in World War I, 1914-1920, in: Tauber, Über den Weltkrieg 2009, p. 40; Toronto World, 12 October 1915, p. 1.

- ↑ Zgórniak, Marian: Polacy w armii monarchii austro-węgierskiej w czasie I wojny światowej, [Poles in the army of the Austro-Hungarian Empire during World War I], in: Studia i Materiały do Historii Wojskowości [Studies and Materials for Military History], vol. 30, Warsaw 1988, pp. 227-46; Watson, Alex: Fighting for Another Fatherland. The Polish Minority in the German Army, 1914-1918, in: English Historical Review, 126/522 (2011), pp. 1137-66.

- ↑ Czerep, Stanisław: II Brygada Legionów [The Second Brigade of the Legions], Warsaw 1991.

- ↑ Mleczak, Jan: Akcja werbunkowa Naczelnego Komitetu Narodowego w Galicji i Królestwie Polskim w latach 1914-1916 [The recruitment campaign of the Supreme National Committee in Galicia and the Polish Kingdom in the years 1914-1916], Przemyśl 1988, pp. 113-69; Przeniosło, Marek: Raporty i korespondencja oficerów werbunkowych Departamentu Wojskowego Naczelnego Komitetu Narodowego 1915-1916. Ziemia Radomska [Reports and correspondence of recruitment officers of the Military Department of the Supreme National Committee from 1915 to 1916. The land of Radom], Kielce 2007.

- ↑ Wrzosek, Mieczysław: Polski czyn zbrojny podczas pierwszej wojny światowej 1914-1918 [The Polish armed struggle during the First World War 1914-1918], Warsaw 1990, pp. 360-73; Lipiński, Wacław: Walka zbrojna o niepodległość Polski w latach 1905-1918 [The armed struggle for Polish independence in the years 1905-1918], Warsaw 1931, pp. 191-201.

- ↑ Nałęcz, Tomasz: Polska Organizacja Wojskowa 1914-1918 [The Polish Military Organization 1914-1918], Warsaw 1984; Lipiński, Walka zbrojna [Armed struggle] 1931, pp. 144-73.

- ↑ Wrzosek, Polski czyn [Polish armed struggle] 1990, pp. 280-84, 310-34, 390-456; Lipiński, Walka zbrojna [Armed struggle] 1931, pp. 245-320.

- ↑ Lipiński, Walka zbrojna [Armed struggle] 1931, pp. 359-66, 457-82; Wrzosek, Polski czyn [Polish armed struggle] 1990, pp. 334-45, 367-407.

- ↑ On 15 February 1915, the 20th Corps, consisting mainly of Latvians, enabled the First Army to retreat near Augustów. However, it was completely destroyed in the process, leaving 20,000 Latvian soldiers dead and making it the military operation with the highest number of dead Latvian soldiers in the entire war. 9,000 of the Latvian Riflemen – more than one third of their total – fell during the “Christmas Battles” in December 1916 and January 1917, making them known far beyond the region. See: Rauch, Georg von: The Baltic States. The Years of Independence. Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, 1917-1940, Berkeley et al. 1987, p. 26; Bleiere, Daina: History of Latvia. The 20th century, Riga 2006, pp. 78, 86.

- ↑ Raun, Tovio U.: Estonia and the Estonians, Stanford 2001 (1987), p. 101.

- ↑ Jussila, Osmo / Hentilä, Seppo Nevakivi: From grand duchy to modern state. A political history of Finland since 1809, London 1999, p. 91.

- ↑ For example, the future White Guard Generals Mannerheim, Löfström and Thesleff. Upton stated that the most common reason young Finnish men voluntarily joined the army was a lust for adventure. See: Upton, Anthony F.: The Finnish Revolution 1917-18, Ann Arbor 1981, p. 15.

- ↑ Upon its formation in November 1918, it was briefly called the “Eiserne Brigade”. See: Pajur, Ago: Der Ausbruch des Landeswehrkrieges. Die estnische Perspektive, in: Forschungen zur baltischen Geschichte 4 (2009), p. 146.

- ↑ Sammartino, Annemarie: The impossible border. Germany and the east, 1914-1922, Ithaca 2010, p. 44; Goltz, Rüdiger von der: Meine Sendung in Finnland und im Baltikum, Leipzig 1920, p. 156.

- ↑ Bleiere, History 2006, p. 94.

- ↑ For a comprehensive overview of the formation of the Lithuanian army see: Lesčius,Vytautas: Lietuvos kariuomenė nepriklausomybės kovose, 1918-1920 [The Lithuanian Army in the Independence Wars], Vilnius 2004.

- ↑ Raun, Estonia 2001, p. 108.

- ↑ Initially, the Estonian government had prohibited the enlistment of Baltic Germans into the Estonian army. See: Pajur, Der Ausbruch 2009, pp. 156f.

- ↑ Brüggemann, Karsten: Die Gründung der Republik Estland und das Ende des “Einen und unteilbaren Russland”. Die Petrograder Front des russischen Bürgerkriegs 1918-1920, Wiesbaden 2002, p. 197.

- ↑ Stoker, Donald J.: Britain, France, and the naval arms trade in the Baltic, 1919-1939. Grand Strategy and Failure, London 2003, pp. 12-20.

- ↑ Bullock, David: The Russian Civil War 1918-21, Oxford 2008, p. 96.

- ↑ Brüggemann, Karsten: “Foreign Rule” during the Estonian War of Independence 1918-1920. The Bolshevik Experiment and the “Estonian Worker's Commune”, in: Journal of Baltic Studies 37/2 (2006), pp. 210-26.

- ↑ Kipel', Vitaǔt / Kipel', Zora: Byelorussian Statehood. Reader and Bibliography, Minsk 1988, p. 188.

- ↑ Bermondt-Avalov himself stated he commanded over 55,000 men, 40,000 of whom were German nationals. This total figure was most likely exaggerated. See: Rauch, Baltic States 1987, pp. 68f; Sammartino, Impossible Border 2010, p. 66.

- ↑ Romeyko, Marian: Przed i po maju [Before and after May], Warsaw 1985, pp. 27ff, 107ff; Romer, Jan Edward: Pamiętniki [Memoirs], Warsaw 2011, pp. 179-82, 280, 282.

Selected Bibliography

- Gross, Gerhard Paul (ed.): Die vergessene Front - der Osten 1914/15. Ereignis, Wirkung, Nachwirkung, Paderborn 2006: Schöningh.

- Lesčius, Vytautas: Lietuvos kariuomenė nepriklausomybės kovose, 1918-1920. Monografija (The Lithuanian Army in the Independence Wars, 1918-1920. A monograph), Vilnius 2004: Generolo Jono Žemaičio Lietuvos karo akademija.

- Lipiński, Wacław: Walka zbrojna o niepodległość Polski w latach 1905-1918 (Armed struggle for Polish independence in the years 1905-1918), Warsaw 1990: Volumen.

- Liulevicius, Vejas Gabriel: War land on the Eastern front. Culture, national identity and German occupation in World War I, Cambridge 2000: Cambridge University Press.

- Sammartino, Annemarie: The impossible border. Germany and the east, 1914-1922, Ithaca 2010: Cornell University Press.

- Stone, Norman: The Eastern front, 1914-1917, London; Sydney; Toronto 1975: Hodder and Stoughton.

- Wrzosek, Mieczysław: Polski czyn zbrojny podczas pierwszej wojny światowej, 1914-1918 (The Polish military contribution during the World War, 1914-1918), Warsaw 1990: Wiedza Powszechna.