Early Career↑

René Viviani (1863-1925), whose father was a naturalised lawyer with Italian origins living in French Algeria, was born in 1863 in Sidi bel Abbès. After studying law, he settled in Paris and soon became a specialist in labour affairs, defending unions and workers on strike. A close collaborator of Alexandre Millerand (1859-1943), Viviani was elected deputy for Paris in the 1893 elections and became part of the chamber’s newly formed socialist group. In the following years, he contributed to the establishment of socialism as an important force in the French party system, being one of the founders of the party’s journal L’Humanité in 1904. As a determined reformist he opposed Marxism as the theoretical basis of socialism and refused to join the unified socialist party, Section française de l'internationale ouvrière (SFIO), in 1905 because of its strict interdiction on party members participating in bourgeois governments. Consequently, Viviani agreed when Georges Clemenceau (1841-1929) offered to make him France’s first minister of labour in the government he formed in 1906 - a position Viviani held until 1910.

President of the Council↑

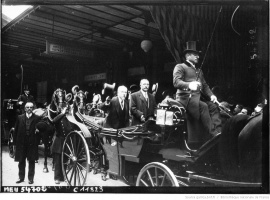

Following the elections of May 1914, which represented a substantial victory for the left, Viviani formed his first government, composed of radicals and independent socialists, in which he also served as foreign minister. At the height of the July Crisis, Viviani accompanied President Raymond Poincaré (1860-1934) on a state visit to Russia that had been planned before the crisis had started. Viviani, inexperienced in foreign affairs, only played a secondary role in the diplomatic negotiations with the Russian government: sincerely committed to peace and wishing to promote a diplomatic solution to the crisis, he was unable to counterbalance the influence of Poincaré and the French ambassador Maurice Paléologue (1859-1944), both of whom advocated a position of firmness against Austria-Hungary and Germany. Back in France, Viviani continued to work for peace: influenced by his former socialist colleagues, he ordered a ten kilometer retreat of the French army from the Franco-German border, in an attempt to demonstrate France’s “defensive” intentions.

When the war finally proved inevitable, it was Viviani who read Poincaré’s famous declaration calling for a Union sacrée to the French Chamber of Deputies. He was also the author of the call “Aux femmes françaises” summoning women to replace the men who had gone to war in the fields. By reshuffling his government on 26 August 1914, he tried to put this “sacred union” into practise: the new cabinet now included two socialists and leading representatives of all republican parties. In the following months, Viviani was a rather weak premier who tried to moderate between President Raymond Poincaré, War Minister Alexandre Millerand, Commander in Chief Joseph Joffre (1852-1931) and the parliamentarians of the two chambers. Having no clear personal position in the crucial question of political control over military affairs, he definitely suffered from a lack of authority. Viviani resigned as head of government in October 1915, but continued to serve as minister of justice and temporarily as minister of public instruction in the following cabinets led by Aristide Briand (1862-1932) and Alexandre Ribot (1842-1923).

After the War↑

After the war, Viviani was re-elected as a deputy in 1919 and elected senator in 1922, but he no longer played a major role in French politics. Seriously ill and unable to work from 1923, he ultimately died on 6 September 1925.

Daniel Mollenhauer, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München

Section Editor: Emmanuelle Cronier