Introduction↑

Major General Sir Charles Vere Ferrers Townshend (1861-1924) commanded the 6th (Poona) Division of the Indian army from April 1915 until its surrender during the siege of Kut-al-Amara in April 1916. A graduate of the Royal Military College, Sandhurst and commissioned in the Royal Marine Light Infantry, Townshend first rose to fame in 1895, when he was besieged at Chitral Fort in India’s North-West Frontier for six weeks. His besieged force, numbering around 400 Sikhs, Kashmiris, and local Chitralis, held on to the fort until a large relief force arrived from Peshawar and broke the siege. Townshend’s defence of Chitral Fort was front-page news in the British press, where it was often compared to the Siege of Lucknow during the Indian Rebellion of 1857 and visualized in sketches in The Graphic. Townshend and other British officers who withstood the siege were lionized in the press as the very best of the British army’s officer class, and, as the Glasgow Herald put it, for defending the fort "against a bold, skilful, and overwhelmingly numerous enemy."[1] Later, he fought at the Battle of Omdurman in September 1898 and as a staff officer during the Second Anglo-Boer War of 1899 to 1902.

First World War↑

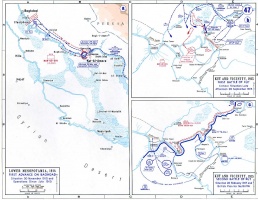

After spending the first seven months of the war in India, Townshend was put in command of the 6th (Poona) Division in April 1915. Following a string of battlefield victories, including Amara, Es Sinn, Nasiriyah, and Kut, Townshend preferred to consolidate his gains around Amara and Kut, fearing that an advance towards Baghdad would stretch too thinly the Division’s supply lines. General Sir John Nixon (1857-1921), pressured by the War Cabinet to make up for the loss of British prestige after the evacuation of the Dardanelles, ordered him to march on. Halted at Ctesiphon in November 1915, Townshend fell back to the town of Kut in December. There, Townshend planned to hold his ground, await a relief force from Basra, and provide much-needed rest to his men; almost half of the Division’s officers were sick or wounded. He was also concerned that if he pushed his Indian soldiers too far, their morale would plummet and discipline would collapse. Townshend was no stranger to siege warfare. He had taken part in the Nile Expedition to relieve General Charles Gordon’s (1833-1885) forces at Khartoum between 1884 and 1885, and, a decade later, was himself besieged in India’s North-West Frontier. Besieged at Kut, he informed Nixon, wrongly, it turned out, that his men had little more than a month’s rations left, putting undue pressure on the relief force to quickly reach the besieged British and Indian soldiers.

Multiple attempts to relieve British and Indian soldiers at Kut in March and April 1916 were unsuccessful. Food and medical supplies were dropped by the Royal Flying Corps, but often ended up in the Tigris River or in the hands of Ottoman army soldiers. Another attempt to provide almost a month’s worth of supplies by a slow-moving, steel-plated steamship chugging up the Tigris, never made it to Kut. Inside the besieged city, disease, mostly dysentery, malaria, and enteritis, were widespread, and both British and Indian soldiers were near starvation and reduced to eating horse meat. The relief force, too, had suffered 23,000 casualties in its effort to lift the siege. After failed attempts to bribe the Ottoman army to release British and Indian soldiers in exchange for cannons and 1 million pounds in cash, Townshend, broken down both physically and mentally, unconditionally surrendered Kut on 29 April 1916. After Townshend’s surrender – the largest surrender of British arms since Lord Cornwallis at Yorktown in 1781 – he was held in captivity first on Halki (modern-day Heybeliada) and then on Prinkipo Island (modern-day Büyükada) near Istanbul for the rest of the war. In captivity, Townshend grew close to the Ottoman Minister of War, Ismail Enver Pasha (1881-1922), holding private meetings with Enver at the Ottoman Ministry of the Navy and went as far as to defend Enver and the Ottoman army’s treatment of British and Indian prisoners of war (POWs), while simultaneously criticizing the British army’s treatment of Ottoman POWs in Egypt. Near the end of the war, Townshend played a small part in negotiating the Armistice of Mudros on behalf of the new Ottoman government led by Ahmed Izzet Pasha (1864-1937).

Post-War↑

Townshend returned to Britain in October 1918 and resigned from the British army in January 1920. At the time, the press still praised him as the "Hero of Kut". That year, he released his memoirs, a tenacious defence of his conduct in the war, titled My Campaign in Mesopotamia. In November 1920, distressed by the policies of the Conservative-Liberal coalition, Townshend was elected as the Independent Conservative Member of Parliament for The Wrekin, Shropshire. But as the condition of British and Indian POWs after Kut became known in public, thanks to the findings of the Mesopotamia Commission Report of 1917, Townshend’s reputation suffered. While Townshend’s wartime captivity was comfortable bordering on luxurious – he was allowed to walk freely on Halki and Prinkipo, swim in the Sea of Marmara, and was given a complimentary aide-de-camp from the Ottoman navy – British and Indian POWs, especially the rank and file, were forcibly marched to prison camps in Anatolia, often beaten and starved. More than half of those captured at Kut died en route to the prison camps or in captivity. Townshend did himself little favours in political circles by openly criticizing the British government’s policy in the Middle East and by arguing in the House of Commons that the Treaty of Sèvres was a political miscalculation that would leave the region unstable for decades. But to others, Townshend and Kut were examples of Anglo-Saxon perseverance in the face of insurmountable odds. After the General Strike of 1926 came to an unsuccessful end, one Labour Member of Parliament compared the struggle of organized labour to that of Townshend and the 6th (Poona) Division a decade earlier. In 1928, Townshend’s cousin, who authored the first biography of Townshend, Townshend of Chitral and Kut, favourably compared the defence of Kut to the earlier defence of Chitral Fort. A lifelong Francophile, Townshend died in Paris in May 1924, his public profile never fully rehabilitated.

Justin Fantauzzo, Memorial University of Newfoundland

Section Editor: Pınar Üre

Notes

- ↑ "Our Latest Little War", Glasgow Herald, 28 October 1895, p. 4.

Selected Bibliography

- Coates Ulrichsen, Kristian: The First World War in the Middle East, London 2014: Hurst.

- Gardner, Nikolas: The siege of Kut-al-Amara. At war in Mesopotamia, 1915-1916, Bloomington 2014: Indiana University Press.

- Johnson, Robert: The Great War and the Middle East. A strategic study, Oxford 2016: Oxford University Press.

- Rogan, Eugene L.: The fall of the Ottomans. The Great War in the Middle East, New York 2015: Basic Books.