The Tannenberg Myth in Soviet Russia and the Russian Émigré Community↑

In Soviet Russia, military theorists, particularly former imperial army officers serving the Bolsheviks or so-called "war specialists," studied the Battle of Tannenberg up until the eve of the Second World War in preparation for a new conflict. Soviet military literature attributed the defeat on the Eastern Front not to the success of German armaments, but rather to the mediocrity of the Russian senior military leadership. Military theorists doubted the independence of the decision-making of the Russian command, which had agreed to take on the thankless task of diverting the Germans from the French theatre of military action. The leadership talent of the German generals was not considered a factor, the generals’ only achievement being the ability to exploit the situation on the ground.

The reinterpretation of the negative experience in East Prussia took on particular significance for the military personnel in the Russian émigré community. After being defeated twice in WWI and the Civil War, the symbolic and conceptual world of the Russian officer class had been shaken and in need of a group identity in an alien cultural environment. This end was served by mythologizing the old Russian army and the self-sacrificing heroism of the Russians in East Prussia in the name of their duty to the allied cause. It is this interpretation that has taken hold in contemporary Russian cultural memory, thanks to literary works and their nostalgia for a "Lost Russia."[1]

Tannenberg Myth in the Weimar Republic and the Third Reich↑

In the German Empire, the mythologizing of the events in East Prussia was aimed at forming the interconnected concepts of the Russian occupation and the triumph of German arms. Topographically closer to Allenstein, the battle was given its name for symbolic reasons. In 1410 the Teutonic Order suffered a decisive defeat at Tannenberg against the alliance of the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Even though the Russian armies stood in East Prussia in August 1914, the Battle of Tannenberg avenged the German army of the old trauma and restored the legacy of the Teutons. In the context of World War One, Tannenberg was compensation for Germany’s defeat in the Battle of the Marne and the basis for the stabilization of the previously broken-down civil peace.

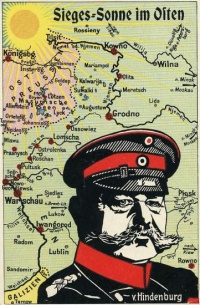

The advent of the cult of Paul von Hindenburg (1847-1934) – who had been named together with Erich Ludendorff (1865-1937) as head of the Third High Command in 1916 – contributed to the removal of Wilhelm II, German Emperor (1859-1941) from the summit of political power and the establishment of a military dictatorship. Nonetheless, the use of the myth’s symbolic capital for political ends allowed for the preservation of the military values of Wilhelmian society during the transition to a republican form of government. Moreover, it gave birth to the fundamental concepts used by the enemies of Weimar democracy: the “Dolchstosslegende” ("stab-in-the-back" myth), the concept of the "Golden Age" of the Empire, and the desire for authoritarian state structures and military vengeance.The Tannenberg myth also had great significance for the ideological integration of German society during the Weimar Republic. Economic and political crises, the republican state’s lack of legitimacy, and the difficulty of establishing a democratic political culture led to the revival of military authoritarianism. East Prussia, cut off from the rest of the country by the Treaty of Versailles (which the Germans regarded as humiliating), became the embodiment of revanchist ideas and a symbol of the victorious military experience of 1914.

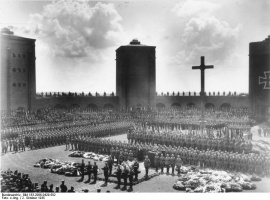

The “völkisch” movement, in which General Ludendorff was heavily involved, made use of the symbolic capital acquired by way of the Battle of Tannenberg. Ousted from the narrative and mythology of the event because of his involvement in the Nazi Party and the Beer Hall Putsch and his quarrels with the Bavarian Generals, Ludendorff tried to unite all paramilitary organizations under the “Tannenbergbund”. A personal and political rupture with Field Marshall Hindenburg during the 10th anniversary of the Battle led to repressive measures against the “Tannenbergbund” by the government. The mass celebrations of the anniversary of the Battle of Tannenberg, which declared Germany’s legal and historical right to the now estranged province of East Prussia, as well as the construction of the large-scale Tannenberg monument[2] symbolized both dislocation and continuity in the transition from empire to republic and from the Weimar Republic to the Third Reich. The idea to erect a monument in honor of the deceased soldiers of the First World War was first expressed by the Social Democratic Reich President Friedrich Ebert (1871-1925). Different towns initially competed for the honor, but no decision was made. The “Nationaldenkmal Tannenberg” was designed by the brothers Johannes (1890-1975) and Walter Krüger (1888-1971). It was built in the shape of a historical German village with a dolmen placed in the middle as a sacrificial altar. Eight large towers, each of which were ascribed a symbolic meaning, composed a massive octahedron with a courtyard for mass ceremonies. The entire space of the monument became a memorial for military organizations, comrades in arms, veterans’ groups, military parades, and, eventually, Hindenburg’s sepulture.

The mourning of fallen compatriots in WWI became one of the authoritarian nation state’s forms of ritual theatre. Tannenberg was not merely a place of remembrance, but also a symbol of the common destiny and renewed spirit of a unified nation. The victory of Field Marshall Hindenburg, who had previously played no part in active political life, in the 1925 presidential elections, did not lead to the consolidation of the Weimar Republic. A cult based on nationalist myth allowed Hindenburg to exclude the parliamentary parties from power and form a government according to his own personal view of the situation (as evidenced by the presidential cabinets of 1929-1933).The Tannenberg myth acquired particular significance in the establishment of the political culture of the early Third Reich. The National Socialists’ political interpreters skillfully exploited the military components of the myth and its authoritarian character, transforming them into the new state’s symbols of power. The belief in the steadfastness of Germany and German militarism was based on the myth of Tannenberg, which exalted the army even after its defeat in WWI. According to the German General Staff, on the eve of the Second World War the Eastern armies were full of self-esteem. It is no accident that the provocation on the Polish border of August 1939, to mask the beginning of World War II, was named "Operation Tannenberg."[3] The monument to the battle, however, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht during the retreat of 1945.

Oxana Sergeevna Nagornaja, South Urals Institute of Management and Economics

Section Editors: Yulia Khmelevskaya; Katja Bruisch; Olga Nikonova

Notes

Selected Bibliography

- Goebel, Stefan: The Great War and medieval memory. War, remembrance and medievalism in Britain and Germany, 1914-1940, Cambridge; New York 2007: Cambridge University Press.

- Hoegen, Jesko von: Der Held von Tannenberg. Genese und Funktion des Hindenburg-Mythos, Cologne 2007: Böhlau.

- Nagornaja, Oxana Sergeevna, Ndiaye, Iwona Anna; Romanowska, Ewa (eds.): 'Syndrom Tannenbergu'. Rosyjska instrumentalizacja wschodniopruskiego doświadczenia doświadczenia ('Syndrome Tannenberg'. Russian instrumentalisation of the East Prussian experience), in: Borussia. Kultura - Historia - Literatura 41, 2007, pp. 202-216.

- Schenk, Frithjof Benjamin: Tannenberg/Grunwald, in: François, Étienne / Schulze, Hagen (eds.): Deutsche Erinnerungsorte, volume 1, Munich 2001: C. H. Beck, pp. 438-454.

- Tietz, Jürgen: Das Tannenberg-Nationaldenkmal. Architektur, Geschichte, Kontext, Berlin 1999: Verlag Bauwesen.