Introduction↑

The Great War was the great destroyer of European empires. The mighty Russian Empire, the conservative anchor of the East for centuries, was the first to collapse. Why? Observers over the past hundred years have offered a number of explanations. Some ventured the proposition that the revolution that toppled the throne and eventually resulted in a communist dictatorship was due to Russian backwardness. In this view, Russia’s attempts to come to terms with modern political and economic systems were late and only superficially successful. Parliaments emerged, but only alongside an unrepentant autocracy. Industry developed, but it was excessively dependent on foreigners and coexisted uncomfortably with a barely transformed Russian countryside. As a result, the entire structure of Russian social and political life was fragile and broke down under the pressure of the war.[1] There is something to this argument, but it is easy to overstate. We certainly should not equate backwardness with weakness. The rapid expansion of Russian power prior to the war was so alarming to German military planners that they pressed their political leadership to find a casus belli with the Romanovs as soon as possible.[2] Neither did “backwardness” mean a lack of adaptability, even resilience. Russia’s industrial infrastructure did shudder at the start of the war, leading to debilitating weapons shortages in 1915, but by the end of 1916 it had recovered so quickly that Russia was out-producing German munitions makers.[3]

Nor was Russia undone by conspiratorial Marxists. Given the long history of the Russian revolutionary movement and the eventual success of the Bolsheviks, it made sense to connect the dots and to see revolutionaries as authors of the Revolution. Nevertheless, few scholars give much credence to a straightforward thesis of subversion. In the first place, no serious analyst either at the time or later attributed the February Revolution of 1917 (which forced the abdication of the Tsar) to successful intrigue on the part of Russia’s beleaguered Social Democrats. Indeed, to the extent that there was coup plotting in early 1917, it was being conducted by conservatives in the military and the royal family.[4] None of those plots had anything to do with the roiling rebellion that actually occurred. Secondly, as we shall see below, by the time that the communists did successfully launch a revolution, in October of the same year, the war effort was already in free fall. Left wing political activism played a role in the revolutionary year of 1917, of course, but it was only one of many factors.

Finally, we can dismiss the idea that Russia lost the war due to military failures, for the Russian army fought badly really only at a few moments. At the Battle of Tannenberg in 1914 and at the Battle of Gorlice-Tarnów in 1915, the Russians did lose entire armies and suffered serious strategic reverses. For long stretches of the war, however, Russian arms were quite successful, taking and recapturing Eastern Galicia and occupying Eastern Anatolia and Northern Persia. More to the point, even the large battlefield setbacks did not spell defeat. As the German Chief of the General Staff, Erich von Falkenhayn (1861-1922), complained, the “East gives nothing back.”[5] German military victories did not translate into political gains. Russia, in his view, was not only undefeated, but was perhaps undefeatable in operational terms. How, then, did the empire collapse? That is the question that the following brief narrative of military campaigns, and political and social change seeks to answer.

Entry into the War↑

The assassination of Franz Ferdinand, Archduke of Austria-Este (1863-1914) on 28 June 1914 by a band of extremist Serbian nationalists caught the Russian political elite by surprise. In truth, Russian foreign policy makers had been wrong-footed quite often by events in the Balkans in recent years. In 1912, Serbia, Montenegro, Greece, and Bulgaria had created a “Balkan Alliance” to pursue their mutual interests on the peninsula. It dawned on the Ministry of Foreign Affairs rather late that the main mutual interest of these states would be to launch an offensive war against the Ottoman Empire. When Russia tried to act the role of benevolent patron and attempted to forestall military action, it was ignored. The Balkan Alliance won its war in 1912, then its members fought among themselves for the spoils in 1913 in a Second Balkan War that left Russia impotently wringing its hands on the sidelines.

In 1914, both the main Serbian political leadership - under Nikola Pašić (1845-1926), the Prime Minister - and the Russian High Command knew that any future battles would involve Austria-Hungary and almost certainly Germany. With a depleted and weary army, Pašić wanted no part of a fight, and the Russians also recognized that the time was not right for aggression. They had just funded a “Great Program” of military expansion that would not bear fruit for several years, and they had no desire to start a war on their own initiative. The German politicians and propagandists who accused Russia of starting the war to achieve its own aggressive ends believed that Russia had long-standing goals it sought to achieve by conquest, such as the establishment of imperial hegemony in the Balkans, expansion into Slavic territories in Eastern Europe like Galicia, and the domination of the Straits. These were indeed foreign policy goals of the Russian Empire, and they became increasingly intransigent war aims as the conflict dragged on. But neither the German propagandists nor those more recent historians who have argued the case for Russian “guilt” have ever been able to provide any real evidence that Russia created the diplomatic conflict known as the “July Crisis” or even that the key decision makers in St. Petersburg thought that war in 1914 was a good idea.[6] The preponderance of evidence suggests instead that the crisis was initiated by a group of radical Serbian nationalists and was turned into a casus belli by Austria.

Continental war during the previous Balkan crises had been averted because of mutual non-intervention on the part of the Austrians and Russians. Now that this balance had been ruptured, Russia faced a different political calculus. Notes taken at the crucial meetings of the Russian Council of Ministers late in July in response to the deepening crisis reveal that the primary concern of top government officials was maintaining Russia’s status as a Great Power, not in using the opportunity for an expansionist war. They understood the dangers of war. Several indeed predicted that it might end in the collapse of their own regime. But it seemed more perilous to back down once more. What if Russia were to become another China, another Ottoman Empire, another second tier empire ripe for dismemberment by the other Great Powers? Confusion and indecision marked the final days of peace in St. Petersburg, as the Tsar hesitated before escalating the conflict. In the end, the military and government pursued the policy recommended by the Council of Ministers – attempting to deter Austro-German action through diplomacy backed by force and resolving to go to war with Austria if it were to invade Serbia, even at the risk of a greater continental war.[7]

Russia was in a reactive mode throughout the crisis. On 23 July, Austria issued its ultimatum to Serbia. On 26 July, Nicholas II, Emperor of Russia (1868-1918) responded by ordering all military districts in European Russia to move to a war preparation footing. On 28 July, Austria declared war on Serbia. Later that day, Nicholas took the shaky step of ordering only a partial mobilization (against Austria, not Germany) in the hopes of localizing the conflict. This decision horrified the military command, who warned Nicholas that if they went through with a partial mobilization, it would make a rapid general mobilization impossible. The German border would be left undefended in the first weeks of the war. Nicholas waffled, but he finally saw the military logic and ordered a general mobilization on 30 July, late enough to cause some confusion but not so late that the mobilization plans were derailed. The general mobilization orders were actually a relief to the German General Staff, who had planned to mobilize regardless of Russia’s decision and now could try to paint their march to war as a defensive measure against the Russians.[8] On 1 August 1914, Germany declared war on Russia, turning the Third Balkan War into a continental and, quite rapidly, a world war.

Military Campaigns, 1914-1916↑

1914↑

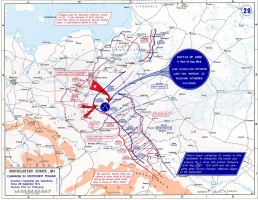

Russia’s mobilization and war plan was predicated on the (correct) assumption that it would be fighting a two-front war with enemies themselves engaged on multiple fronts. Russian military planners had promised their French allies that they would attack Germany shortly after the declaration of war, and they did, crossing the border on 11 August 1914, engaging the enemy in force on 17 August, and winning their first battle (at Gumbinnen) on 20 August. On the same day that the Russian First Army prevailed at Gumbinnen, four Russian armies (the Third, Fourth, Fifth, and Eighth) invaded Austrian Galicia. The last days of August were devastating, however. As the Austrians held off the Russian advance at Krasnik and Komarów, the Russian northern positions against the Germans in East Prussia collapsed. Russia had intended to use two armies (the First and the Second) to envelop the German Eighth Army, the sole screen left behind in the East, while the Germans made their furious bid to take Paris. General Pavel von Rennenkampf (1854-1918), the victorious commander of the Russian First Army at Gumbinnen, failed to keep contact with his foe, however. The Eighth Army, now under the energetic command of Paul von Hindenburg (1847-1934) and Erich Ludendorff (1865-1937), took the opportunity to wheel southward to surround the surprised other arm of the clumsy Russian pincer, General Aleksandr Samsonov’s (1859-1914) Second Army. On 29 August, the mass of the Second Army was forced to surrender as Samsonov shot himself in disgrace. This battle, which was quickly given the name the Battle of Tannenberg by the Germans to recall a 15th century clash between the Teutonic Knights and the Slavs of the eastern marches, ended Russian hopes for a quick victory and locked the empire into a grueling winter of parrying increasingly deep thrusts of German forces into Russian Poland.

Battle fortunes turned more quickly to the south, where the Austro-Hungarian forces faced their own problems of command and coordination. While the incursion of the Russian Fourth and Fifth Armies stalled, the Third and Eighth Armies pushed forward successfully, taking the key Galician city of L’viv on 3 September. By 11 September, they had moved forward so far that the Austro-Hungarians were forced to order a general retreat. Habsburg forces kept reeling backward all fall. By November, the Russians were at the gates of the ancient Polish capital of Kraków and were scaling the Carpathian Mountains to the south. This enormous success was significant. The conquest of Galicia and the Carpathians threatened the very existence of the Habsburg Empire. By contrast, the string of German victories in the north had bruised Russian pride and eviscerated its prewar cadre army, but the armies stood relatively close to their pre-war borders (see map).

1915↑

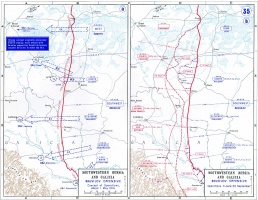

Russia’s grand plans for an invasion of Hungary were dashed when it was beaten to the punch by a successful combined offensive by the Central Powers that began on 2 May 1915 on a line between the Galician towns of Gorlice and Tarnów. The line was manned on the Russian side by the Third Army under the command of General Radko Dmitriev (1859-1918). Dmitriev saw the buildup on his line and begged his superiors for reinforcements, but he was rejected. General Nikolai Ivanov (1851-1919), the Southwestern Front commander and Dmitriev’s superior, decided to beef up his Carpathian invasion force instead. When the blow came, it shattered the Russian line, a common enough occurrence in the Great War. What was unusual was the lack of reserves to plug the holes that had been opened. The Russian High Command harrumphed and refused to allow the Third Army to retreat. Dmitriev, running out of options, gambled his entire army on a surprise counter-offensive. It failed miserably. Thousands of men perished. The XXIV Corps, for instance, with 40,000 billets, stumbled backward with only 1,000 men standing.

The destruction of the Third Army rocked the Russian military back on its heels. The Carpathian invasion force was forced to sprint for the safety of the Ukrainian plains before it was outflanked. In the north, German pressure cracked Russian defenses throughout Poland as the summer wore on, forcing the Narew River in July and capturing the heavily armed fortresses and cities along the Vistula River, including Warsaw, in August. But the planned encirclement of Russia’s armies failed. German forces seized territory, civilians, and more than their fair share of prisoners of war, but did not capture entire armies or force capitulation. German troops made one last desperate attempt to knock Russia out of the war in September and took much of Lithuania and parts of present-day Belarus and Latvia, but they had reached the end of their rope. They would get no closer to central Russia until the demoralized revolutionary Russian army wilted in the summer of 1917.

1916↑

Meanwhile, the Russian army had success on its third major front – in the Middle East. An effort by the Ottoman Empire to surprise the main Russian force in wintry mountain conditions at Sarikamish on 22 December 1914 led to an evisceration of the Ottoman troops through battle and frostbite. Russia prevailed in the first days of the new year. Russian troops then took the initiative, moving westward through historic Armenia and Eastern Anatolia. Worried by the Russian advances, the Ottomans began a policy of genocide against the Christian Armenian population of Eastern Anatolia in April 1915, ostensibly for security concerns. The slaughter of civilians did nothing to tip the scales in the Ottoman’s favor, however. To the contrary, as 1915 turned to 1916, Russian forces successfully occupied Northern Persia and took the key Ottoman Anatolian fortresses of Erzerum and Trabzon. German attempts to prop up their allies in the region and to rally Muslims to a fanciful holy war against Great Britain, France, and Russia were fruitless.

The year 1916 also saw some progress to the north. After a disastrous failed attack near the Belarusian Lake Narach in the late winter, Russian forces on the Southwestern Front surprised Austro-Hungarian troops on 4 June 1916 with an offensive across the entire front. The new Russian front commander, General Aleksei Brusilov (1853-1926), abandoned the standard practice of concentrating his artillery and his attack force on a single sector of the line, forgoing the benefits of a massive barrage and assault in order to exert pressure everywhere and to prevent the Austrian commanders from using their reserves effectively. Weeks later, Russian soldiers had reconquered a large swath of Galicia.

The victory proved to be a partial one, however. Brusilov begged the army commanders to his north to launch their own phase of the offensive in order to cover his right flank. General Aleksei Evert (1857-1926), however, had been chastened by the bloody futility of the Lake Narach battle and delayed as long as he possibly could. In the midst of this uncertainty, Brusilov’s staff squabbled about how to best follow up their initial victories, and ended up choosing the original target of the railway junction of Kovel rather than seeking a more dramatic penetration into Austro-Hungarian territory. Both Evert’s and Brusilov’s troops became bogged down in attacks in swampy ground that brought the offensive to a bruising and incomplete end. The offensive did not knock out any of their enemies and did little except persuade the Romanian government to join the war on the side of the Entente. This proved to be of negative value, as the Romanian army was beaten badly in its first battles and soon required Russian troops to stabilize an even longer front.

Politics and Society, 1914-1916↑

The “Sacred Union”↑

As the preceding summary suggests, Russia did not lose the Great War as a result of foreign conquest. Instead, political and social pressures caused Russia to be the first imperial casualty of the war. This does not mean, however, that main causal factors for the collapse should be sought in the “backwardness” of the pre-war empire or in the dynamics of the revolutionary movement. Nor does it mean that events at the front and in the armed forces were irrelevant to the demise of the Romanov dynasty. To the contrary, the key dynamic that explains the early exit of the Russian Empire is precisely the relationship between the events at the front and the imperial social and political structure.

At first, both governmental and opposition political leaders hoped that the war could be cordoned off from the political and social tensions within the realm. The Tsar proclaimed national unity in front of throngs of cheering crowds in St. Petersburg (soon to be renamed a more Russian-sounding “Petrograd”). Virtually every party that had challenged the pretensions of the autocracy since the formation of the first Russian parliament (Duma) in 1906 declared its desire to fight the war hand in hand with the monarch in a “sacred union.” The Duma went into voluntary recess and stood back to let the military and governmental authorities prosecute the war unchallenged. Only the parties on the far left, such as the Bolsheviks, refused the sacred union, but they were a miserably small party whose platform of revolutionary defeatism (the idea that it would be better for the Revolution if Russia’s troops were to be beaten in the war) held little attraction for the vast majority of Russia’s citizens.

Events at the front soon eroded the “sacred union,” however. Part of the issue was military defeat, but there was much more. In the first place, many citizens and centrist politicians blamed those early defeats on the broader problem of governmental incompetence. It was not simply that the army had lost at Tannenberg or at Gorlice, it was how the army had lost. The mismanagement of reserves was chalked up to low levels of staff officer ability and high levels of cronyism in the military elite. Munitions shortages suggested both poor planning and poor coordination between the military and industrial sectors. The catastrophically bad situation with Russia’s wounded soldiers, who lay untended by the thousands in the first months of the war, spoke again to a lack of foresight and of logistical acumen. Just as importantly, the declaration of martial law in the western sectors of the empire in the first days of the war put civilian affairs in the hands of the top military brass. Several months of violent and exploitative ethnopolitics followed, along with a collapse of the local economy and of law and order. By the spring of 1915, rumblings from dissatisfied civilians in the borderlands were loud enough to shake the faith of Russian centrists in the “sacred union.”

The Summer Crisis, 1915↑

The defeats of the spring and summer 1915 that followed the Battle of Gorlice-Tarnów destroyed the sacred union for good. Not only was Stavka exposed as incompetent once more, but the massive retreat also occasioned substantial social changes, none of them good. Some of the problem was the inevitable result of the German invasion, but much was self-inflicted by the conscious adoption of a scorched earth policy during the retreat. General Nikolai Ianushkevich (1868-1918), the Supreme Commander’s Chief of Staff, issued the following order to all army commanders on 24 June 1915:

As the epithet of “yids” suggests, the scorched earth practices were marked by ethnopolitical violence, especially in the form of virulent anti-Semitism, which flowered everywhere in the west of the empire in these dark days. Lynchings were common, and, as they fled eastward, soldiers frequently took the opportunity to rob and beat civilian populations.

The misguided decision to pursue a scorched earth policy while retreating led to a wave of internal refugees that numbered more than 6 million people by 1917. Epidemic diseases spread quickly, especially typhus and cholera. Within weeks, both germ-based and social pathologies spread across the empire. Ethnic riots broke out in major cities (the largest targeted against Germans in Moscow in May/June 1915), industrial strikes in central Russia became more common and more violent, and peasant unhappiness with inflation became more and more visible. A political response was inevitable in these conditions. A broad coalition of shocked politicians ranging from conservatives on the right to socialists on the left joined together to form a “Progressive Bloc” that demanded changes in the organization of the war effort and greater participation by non-governmental civic leaders in the affairs of state.

The two main aims of the Bloc were:

The Bloc also insisted upon the end of persecution or discrimination on political, ethnic, or religious grounds, and called for the drafting of a bill of Polish autonomy. The Bloc was able to secure the support of the majority of the Duma and the conservative State Council, even with this ambitious program, and it also garnered the support of nearly every member of the Tsar’s own Council of Ministers. The arch-monarchist chairman of that body, Ivan Goremykin (1839-1917), persuaded the Tsar to reject the proposals of the Progressive Bloc, however. Goremykin and Nicholas II instead agreed to disband the Duma and to institute more autocratic rule. The Tsar promptly sacked many of his liberal and centrist ministers, took on the position of military Supreme Commander, and left for the front.

Russia Adrift, September 1915-February 1917↑

The stunned Progressive Bloc mounted no significant protest to this reassertion of monarchical power, but the unrest of the summer did not end. Days after the Tsar’s assumption of military command on 4 September, riots broke out all over the empire upon the announcement that conscription was being widened to include many previously exempt social categories, such as only sons. Labor unrest grew, and the economy continued to decline. The political system had been thoroughly shaken by the events of the summer of 1915. Whatever faith in the government had survived until that date had disappeared. The Duma seethed, and the ministers who had sought a broad-based solution to the wartime crisis were marginalized or dismissed. At the same time, the gravitational center for conservatives in the realm – the Tsar – had departed the scene as well. Bureaucratic anarchy grew in the absence of strong leadership from above. As ministers were appointed and dismissed with dizzying speed over the course of 1916, political dissatisfaction grew and grew.

This unhappiness found its most vocal outlet in November 1916. After a year of continuing repression of liberal and centrist activists and their organizations, another year of inflation and growing economic misery, and increasingly hostile and erratic behavior on the part of the Prime Minister, Boris Shtiurmer (1848-1917), the two main leaders of the Constitutional Democratic Party, Pavel Miliukov (1859-1943) and Vasilii Maklakov (1869-1957), lashed out in speeches in the State Duma. Miliukov angrily recited a list of complaints against Shtiurmer and indeed the Tsar’s entire government before concluding with an accusation that one of Shtiurmer’s close associates was corrupt and possibly in the pay of the German government. "Is this stupidity?" he asked to the applause of the chamber, "Or is it treason?" Maklakov, well known within his party for being cautious and conservative, drew upon the Bible for inspiration. It was as impossible to serve both the Tsar and Russia, he said, as it was to serve both "God and mammon." Tsarist censors quickly moved to prevent the publication of these addresses, leading to entire columns of whited out print in the key newspapers of the day. It did not take long for the public to find out what had been said, though, as handwritten copies of the speeches circulated throughout the country.

The Tsar lost the support even of ultra-conservative monarchists. Upon the Duma taking a recess in mid-November, the right-wing demagogue Vladimir Purishkevich (1870-1920) and a member of the royal family, the Grand Duke Dmitrii Pavlovich (1891-1942), assassinated Grigorii Rasputin (1869-1916), the scandalous advisor to Alexandra, Empress, consort of Nicholas II, Emperor of Russia (1872-1918). This desperate act did not, however, bring order to the governmental administration, and it failed to save the Tsar from himself.

Colonial Rebellion↑

Thus, as the unprecedented pressures of total war created political unrest in all European states and societies, Russia further weakened itself through myopic decision-making. At the front, military leaders botched promising battlefield opportunities and ran civilian affairs in the western borderlands with unprecedented ignorance. In Petrograd, the Tsar himself undermined the war effort by stubbornly refusing the assistance of the very social forces that might have been able to stabilize the army, the country, and his own regime. In short, Russia’s political and military elite primed itself to crack first under the strain of war, and it did.

The first revolutionary rumblings came from Russia’s Central Asian colonies in Turkestan. On 8 July 1916, the government tried to solve a severe shortage of labor in military infrastructure projects by drafting previously exempt Kazakhs, Kyrgyz, and Uzbeks into labor battalions under military discipline. This prospect was unappealing. Even for the few men who might have left their homeland for a war not of their own making, it seemed closer to conditions of convict labor than civic service. When it became clear that the whole process would be marked by corruption and violence, the entire region exploded into rebellion. Khujand saw street battles on 17 July, Samarkand on 20 July, and Tashkent on 24 July. The uprising quickly spread to the steppe, where Russian troops and colonists were greatly outnumbered by Kazakhs already angered by fifty years of Russian colonial rule. By late summer, a full-blown colonial war was underway. Local populations were slaughtered by Russian troops, and Russian colonists were burned out of their villages by engaged and enraged rebels. The revolt was violently suppressed, and hundreds of thousands of Kazakhs and Kyrgyz fled across the Tien-Shan Mountains into China.

Revolutionary Russia at War, 1917-1918↑

The February Revolution↑

The rebellion came to central Russia in February and March of 1917. One of the most beleaguered social groups in wartime Europe as a whole was that of urban women, who were forced to work harder in the paid sector while taking on even more domestic work in a time of increasing shortages. By February 1917, many women in Petrograd had experienced their fill of long lines in the cold pre-dawn hours for bread that often did not arrive in the shops, at least not in time for them to go to work themselves. They took the opportunity of the new socialist holiday of International Women’s Day on 8 March 1917 (23 February 1917 according to the Russian calendar) to take to the streets and to call out other workers to join their protest. As the protest metastasized, the Tsar’s government, unsurprisingly, botched its response. The decision to use force against protestors depended on the willingness of the Petrograd army garrison to support the city’s police. It turned out, however, that garrison soldiers had greater sympathy for the demonstrators than for the regime. In a series of dramatic events, key units mutinied against their officers, joined the crowd on the streets, and drove policemen and other representatives of the old order into a panicked flight from the city. Army commanders sent troops from the front to re-establish order, but once they recognized the scale of the unrest, they reconsidered and recalled their men. General Mikhail Alekseev (1857-1918), Nicholas II’s Chief of Staff, quietly polled the top army leadership, which unanimously recommended that the Tsar abdicate the throne to prevent further revolutionary disorder. Alekseev communicated this recommendation to his Emperor, who accepted it on 15 March 1917, ending more than three hundred years of Romanov rule in Russia.

Freedom or Anarchy?↑

Though generals hoped that the abdication would allow a hastily formed “Provisional” or “Temporary” Government to turn its attention back to the war effort with even greater enthusiasm, the revolution in fact proved to be more thorough. It was a revolt not just against the Emperor or his “German” wife, the Empress Alexandra (who had been born in Darmstadt-Hesse), but against a whole system of social and political injustice. That injustice was as evident within the armed forces as it was elsewhere in society, and soldiers pursued a program of democratization from the very first days of the new order. They insisted upon the right to be treated with respect by their officers, to enjoy equal civic rights and liberties when off-duty, and to elect their own political representation. More radically, they also pressed for the right to elect their own officers, a desire born from the reasonable fear that the conservative officer corps would seek to roll back any revolutionary gains at the first opportunity. Once these gains were achieved, soldiers were able to articulate their own political platform. Though there was of course no unanimity among the millions of men in uniform, all soldiers were vitally interested in questions relating to the war. Why were they fighting? When would it end? Their first program was not pacifistic. Defensism remained strong among soldiers. Indeed, the Revolution even strengthened it by adding defense of “the Revolution” to the still important defense of “the Motherland.” Soldiers generally believed that Germany was looking to invade Russia and to reduce it to a peripheral vassal state, and they were willing to fight to prevent that from happening. But they were less excited about fighting for “the Empire,” and they soon discovered that their desire for a rapid peace on the basis of restoring the prewar borders was shared by the Petrograd Soviet, a council of representatives of the city’s working class headed by the major socialist party leaders in the capital. The anti-imperialist slogan of “Peace without Annexations or Indemnities” rapidly gained traction among soldiers and oriented their political program for the remainder of the revolutionary year.

Revolution and War↑

It was thus a wary Russian army that stayed in the field in the spring of 1917. The disruptions of the Revolution and of democratization made ambitious military planning impossible in March and April. A planned joint offensive with the British and the French had to be postponed. In April, the liberal leader Pavel Miliukov, now the Minister of Foreign Affairs in the Provisional Government, created a scandal by admitting that the new Russian government would not renounce its acquisitive war aims, namely the acquisition of the Turkish Straits. Violent street demonstrations and howls of protest from soldier deputies forced both Miliukov and the Minister of War Aleksandr Guchkov (1862-1936) to resign. The socialist parliamentarian Aleksandr Kerenskii (1881-1970) replaced Guchkov. In May, General Alekseev unwisely made a speech in which he declared that “Peace without Annexations or Indemnities” was a “utopian phrase,” and was fired and replaced as Supreme Commander by General Brusilov. The new military leadership of Kerenskii and Brusilov inherited plans for a summer offensive, and they went forward with the idea. They believed, as their predecessors had, that the army was disintegrating in front of their eyes in a confused babble of meetings and elections, and they believed that only military action could re-instill a sense of purpose and discipline to the troops. The Germans, happy to watch their eastern foe unravel through revolution, had no intention of providing that unity for them by launching an offensive. The only solution appeared to be to launch a new offensive in the name of the Revolution. Brusilov chose Galicia, the ground of his success in the previous year, as the main front in the offensive. This operation, the so-called “Kerenskii Offensive,” started well on 29 June 1917, but it collapsed quickly and disastrously when mutinous troops refused to press into enemy territory and then turned to looting and savaging the local civilian population. The Russian army, the heir to a force that had gone from victory to victory at the vanguard of the empire, would never win another battle. In September 1917, German troops found out just how far their foe had fallen when they launched an offensive against the Latvian port city of Riga and took it easily.

The seizure of Riga and the Ukrainian descent into anarchy in the summer of 1917 demonstrated clearly that the Revolution had put not just the end of autocracy on the political agenda but the end of empire as well. Political entrepreneurs in the borderlands responded to this development eagerly. At first, their claims were modest: a district border revision here, the right to conduct schooling in local languages there. But as the revolution wore on, the political demands became bolder. The idea of replacing the Russian Empire with a federation composed of politically equal ethnic groups became popular in the summer, but the combination of continued Russian chauvinism and the perpetual injunction to defer all important political questions until the convening of a constitutional convention (the Constituent Assembly) after the conclusion of the war led many nationalists to press more openly of independence.

By the end of the summer of 1917, the Russian Empire was visibly and quickly unraveling. Desertion had increased to epidemic levels, and the army could no longer hold its line, even against a foe that was concentrating the vast majority of its troops on another front. With no legitimate authority and a flood of armed men washing across towns, villages, and cities, law and order disappeared. Russian dominance in the imperial space was contested daily, and the economy was in a parlous condition, plagued by key shortages and runaway inflation.

The October Revolution↑

These mammoth problems were difficult, and in some cases, impossible, to solve in any reasonable amount of time, much less in the midst of both a Great War and an epochal revolution. Political leaders in the Provisional Government and in the Petrograd Soviet faced the wrath of dissatisfied civilians daily, and by the summer, some even wondered aloud at the First Congress of Soviets in June whether any party was either courageous or foolhardy enough to assume responsibility for driving events. Immediately, Vladimir Lenin (1870-1924) stood up and proclaimed, “There is such a party!”[11] Lenin’s party, the Bolsheviks, saw a tremendous revival of their fortunes in 1917. Opposed to the war from the start, they now convincingly made the case that they would pull Russia from the war if they assumed power. They also took full advantage of having an anti-imperialist program. Indeed, socialist politicians had repeatedly denounced European empires throughout 1917 and had pioneered the slogan of “national self-determination.” Despite the fact that this phrase has since become associated with United States President Woodrow Wilson (1856-1924), in fact it was the (mostly Menshevik) leaders of the Petrograd Soviet who most vocally forwarded this idea and forced Miliukov to adopt it in the Provisional Government’s Declaration of War Aims on 9 April 1917. Wilson, indeed, neither included national self-determination as a goal in his Fourteen Points in 1918 nor clung very firmly to the idea during the Paris Peace Conference.[12] The Bolsheviks fully endorsed this anti-imperial language, and they made a convincing case to soldiers and others that they shared the broad goals of a peace without annexations and a postwar system based on the principles of national self-determination.

In November, the spiraling collapse of the empire intersected with the rise of the Bolsheviks. As men in uniform increasingly turned toward the Bolsheviks and their platform, so too did key sectors of the urban working class. In the fall of 1917, the Bolsheviks finally established their dominance in urban soviets of workers and soldiers and promptly began forwarding the slogan of “All Power to the Soviets,” that is, the deposing of the Provisional Government, now headed by Kerenskii as the Prime Minister. On 7 November (25 October on the Russian calendar), Lenin, Lev “Leon” Trotskii (1879-1940), and their compatriots launched a successful coup that overthrew the Provisional Government. The coup, remarkably, had been advertised ahead of time by the Bolsheviks’ own newspaper, Pravda. The fact that the Provisional Government could not defend itself even with full warning was evidence enough that it had lost whatever authority it had garnered in the wake of the February Revolution. With the ministers arrested or put to flight, the Bolsheviks announced that all power would henceforth reside in the hands of the worker’s councils. Though at first the soviets included representatives from several socialist parties, that condition would only last a few more months, as the Bolsheviks drove one group after another out of the soviets and into embittered opposition. By the time of the armistice on the Western Front, in November 1918, Soviet Russia was effectively a one-party state.

Exiting the War↑

The coup was the beginning, not the end, of the Bolshevik Revolution, and the Bolshevik leadership was heavily constrained in its actions by the conditions that Russia faced in late 1917. By far the most significant condition was that the Great War continued unabated. Lenin had come to power on a platform of getting Russia out of the war, the Russian army was in shambles, and Germany had tremendous incentive to close its second front in order to focus its energies on one last offensive in the west in the spring of 1918. A ceasefire came days after the Bolshevik coup, and peace negotiations began in the citadel of Brest-Litovsk soon afterwards. There was much to discuss at those negotiations, including the status of the independent Ukrainian negotiators who arrived to represent the interests of the Ukrainian parliament (or Rada), but the outcome was never really in doubt. The Bolsheviks had to sign a peace in order to survive, and the German negotiators used this immense leverage in ruthless ways by demanding the cession of all of the old Russian western borderlands and imposing unequal trade deals with its neighbors. The Bolsheviks surprisingly delayed the inevitable with a spirited discussion of the meaning of “national self-determination” with smirking German and Austrian diplomats and with a truly radical announcement that they would both refuse to fight any longer and refuse to sign a punitive peace. The Germans called their bluff, sweeping eastward along rail lines and taking ancient Russian cities like Pskov. They got close enough to Petrograd to attack it with bomber sorties on 27 February 1918.[13] Out of troops and out of options, the Soviet delegation signed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk on punitive terms on 3 March 1918, bringing an end to Russia’s participation in the Great War.

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk did not, however, end warfare in Eastern Europe. To the contrary, fighting continued well after the November armistice and the eventual Versailles peace in the west. Within days of the signing of the Treaty, Ukrainian forces loyal to the Ukrainian parliament (Rada) and supported in force by the German army clashed with Ukrainian formations from the eastern city of Khar’kiv supported fully by the Bolshevik capital in Moscow. German troops won and spread quickly to the east, making it to Rostov-on-Don and Taganrog on the northeastern tip of the Sea of Azov. Ukraine had gained its independence from Russia, but only at the price of dependence on Germany. Germany’s collapse at the end of 1918 therefore left Ukraine in a precarious position. In 1919, both the Bolsheviks and the new Polish government made a play to take Kiev. While the Poles had initial success, the invasion sparked a Soviet-Polish War that led the Red Army to the outskirts of Warsaw in 1920. The failed effort to take the Polish capital led to a more comprehensive peace agreement in the Treaty of Riga (1921). This treaty established a partition of Ukraine, with Poland taking Galicia and Soviet Russia taking the rest. Though Ukrainian nationalists failed to establish an independent state, others in the region were more fortunate, as new states were created in Finland, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. The Poles and the Soviets were plainly the strongest players in the new regional power structure. Lithuanian statesmen were forced to give way on many territorial claims in the face of Polish hostility, and Soviet forces fought in the Finnish Civil War (1918) that established the independence and borders of Finland.

The territorial integrity of Russia east of these nationalizing borderlands was also in doubt throughout the years of the Russian Civil War. Anti-Bolshevik forces led by former imperial generals fought nasty skirmishes with Red forces throughout Southern Russia in the spring of 1918. Then, in May 1918, 35,000 prisoners of war formed into a “Czech Legion,” rebelled while traveling on the Trans-Siberian Railway. The opening of the Siberian front marked the start of a countrywide civil war. National issues were relevant in many places, most notably in the Caucasus region, where ethnic groups jockeyed with Soviet forces, White Russian troops, the crippled Ottoman Empire, and the distracted British Empire for power. After several failed efforts at creating independent states, federations of small peoples, and even city-wide communes, the region was Sovietized in 1920 and 1921. A similar process took place in Central Asia. In regions heavily populated with ethnic Russians, the legacy of the war was also strongly felt. Many of the soldiers who had deserted in 1917 had brought their weapons and taste for violence home with them. Most resisted conscription by Red and White forces, but they often took part in local struggles, including the hundreds of small-scale skirmishes between peasant communities and the would-be states that sought their grain and their allegiance. It was not the red flag that was the icon of power during the civil war. It was the “man with a gun.”[14]

Conclusion↑

The Russian experience in the Great War was a perfect example of what is meant by the phrase “Total War.” It was an integrated experience, with military, social, economic, and political developments immediately and intimately interacting throughout the conflict. It may, in fact, be a mistake to ask, as generations of scholars have done, whether the war caused, or helped to cause, the Russian Revolution. From 1914 onwards, the state and society were engaged in something we might call the war-revolution, as combat, economic distress, social transformation, and political change moved hand in hand together, leaving a trail of blood behind as it moved forward to an uncertain future.

Joshua A. Sanborn, Lafayette College

Section Editors: Boris Kolonit͡skiĭ; Nikolaus Katzer

Notes

- ↑ Malia, Martin: The Soviet Tragedy: A History of Socialism in Russia, 1917-1991, New York 1994, p. 56.

- ↑ Mombauer, Annika: Helmuth von Moltke and the Origins of the First World War, Cambridge 2001, pp. 173-176.

- ↑ Stone, Norman: The Eastern Front 1914-1917, New York 1975, pp. 12-13.

- ↑ I have briefly addressed the question of coup plotting elsewhere, in an extended review essay. Sanborn, Joshua: Liberals and Bureaucrats at War, in: Kritika 8/1 (2007), pp. 141-162.

- ↑ Showalter, Dennis: Tannenberg, Clash of Empires, Washington D.C. 2004, p. 340.

- ↑ A recent, though unsuccessful, attempt to prove Russian authorship of the war is McMeekin, Sean: The Russian Origins of the First World War, Cambridge, MA 2011.

- ↑ Lieven, D. C. B.: Russia and the Origins of the First World War. New York 1983; Bobroff, Ronald P.: War Accepted but Unsought. Russia’s Growing Militancy and the July Crisis, 1914, in: Levy, Jack S./Vasquez, John A. (eds.): The Outbreak of the First World War. Structure, Politics, and Decision-Making, Cambridge 2014, pp. 296-328.

- ↑ Mombauer, Heinrich von Moltke 2001, p. 206.

- ↑ General Ianushkevich, telegram to army generals, 11 June 1915, State Archive of the Russian Federation (GARF) fond (collection) 215, opis (register) 1, delo (file) 249, listy (sheets) 7-8.

- ↑ Cited in Pearson, Raymond: The Russian Moderates and the Crisis of Tsarism, 1914-1917, Basingstoke 1977, p. 51.

- ↑ Fitzpatrick, Sheila: The Russian Revolution (second edition), Oxford 1994, p. 52.

- ↑ Throntveit, Trygve: The Fable of the Fourteen Points. Woodrow Wilson and National Self-Determination, in: Diplomatic History 35/ 3 (2011), pp. 445-481, http://scholar.harvard.edu/files/throntveit/files/fable_of_the_fourteen_points_dh_35.3_june_2011.pdf (retrieved 28.10.2014).

- ↑ Wheeler-Bennett, John W.: Brest-Litovsk. The Forgotten Peace, March 1918, London 1938, p. 265, https://archive.org/details/brestlitovskthef018745mbp (retrieved 28.10.2014), citing Philips Price, M.: My Reminiscences of the Russian Revolution. London 1921, p. 250.

- ↑ See Buldakov, V. P.: Ot voiny k revoliutsii. Rozhdenie cheloveka s ruzh’em, [From War to Revolution. The Birth of the Individual with a Gun] in: Volobuev, P. V. (ed.): Revoliutsiia i chelovek. Byt, nravy, povedenie, moral [Revolution and the Individual. Life, Customs, Behavior, Morals], Moscow 1997, pp. 55-75.

Selected Bibliography

- Bakhturina, A. I︠U︡.: Okrainy rossiĭskoĭ imperii. Gosudarstvennoe upravlenie i nat︠s︡ionalʹnai︠a︡ politika v gody Pervoĭ mirovoĭ voĭny, 1914-1917 gg. (Borderlands of the Russian Empire. State administration and nationality politics during the First World War, 1914-1917), Moscow 2004: Rosspėn.

- Fuller, William C.: The foe within. Fantasies of treason and the end of Imperial Russia, Ithaca 2006: Cornell University Press.

- Gaida, Fedor Aleksandrovich: Liberalʹnaia oppozitsiia na putiakh k vlasti, 1914-vesna 1917 (The liberal opposition on the road to power, 1914-spring 1917), Moscow 2003: Rosspėn.

- Gatrell, Peter: A whole empire walking. Refugees in Russia during World War I, Bloomington 2011: Indiana University Press.

- Gatrell, Peter: Russia's First World War. A social and economic history, Harlow 2005: Pearson/Longman.

- Hagen, Mark von: War in a European borderland. Occupations and occupation plans in Galicia and Ukraine, 1914-1918, Seattle 2007: University of Washington Press.

- Holquist, Peter: Making war, forging revolution. Russia's continuum of crisis, 1914-1921, Cambridge 2002: Harvard University Press.

- Lieven, Dominic C. B.: Russia and the origins of the First World War, New York 1983: St. Martin's Press.

- Lincoln, W. Bruce: Passage through Armageddon. The Russians in war and revolution, 1914-1918, New York 1986: Simon and Schuster.

- Lohr, Eric: Nationalizing the Russian Empire. The campaign against enemy aliens during World War I, Cambridge 2003: Harvard University Press.

- Nachtigal, Reinhard: Die Murmanbahn. Die Verkehrsanbindung eines kriegswichtigen Hafens und das Arbeitspotiential der Kriegsgefangenen (1915 bis 1918), Grunbach 2001: Greiner.

- Nagornaja, Oxana Sergeevna: Drugoi voennyi opyt. Rossiiskie voennoplennye Pervoi mirovoi voiny v Germanii (1914-1922) (The other military experience. Russian prisoners of war during the First World War in Germany (1914-1922)), Moscow 2010: Novyj chronograf.

- Pearson, Raymond: The Russian moderates and the crisis of tsarism, 1914-1917, London; Basingstoke 1977: Macmillan.

- Reynolds, Michael A.: Shattering empires. The clash and collapse of the Ottoman and Russian Empires, 1908-1918, Cambridge 2011: Cambridge University Press.

- Rostunov, Ivan Ivanovich: Russkii front pervoi mirovoi voiny (The Russian Front during the First World War), Moscow 1976: Nauka.

- Sanborn, Joshua A.: Imperial apocalypse. The Great War and the destruction of the Russian Empire, Oxford 2014: Oxford University Press.

- Showalter, Dennis: Tannenberg. Clash of empires, Dulles 2004: Potomac Books Inc..

- Stoff, Laurie: They fought for the motherland. Russia's women soldiers in World War I and the revolution, Lawrence 2006: University Press of Kansas.

- Stone, Norman: The Eastern front, 1914-1917, London; Sydney; Toronto 1975: Hodder and Stoughton.

- Wildman, Allan K.: The end of the Russian imperial army, 2 volumes, Princeton 1980-1987: Princeton University Press