Escape and Expulsion↑

From the spring of 1915, the Austro-Hungarian Empire found itself fighting on three distinct fronts: Russia, Serbia and Italy. The majority of the border regions were therefore absorbed into the so-called “war zone”. Moreover, between 1914 and 1915, vast portions of Habsburg territory had been invaded.

This led to 360,000 Jews fleeing from the eastern regions (1914, 1915 and 1916), followed by the evacuation of 130,000 Poles from Galicia (1914-1915), 300,000 Ruthenians from Galicia and Bukovina (1914 and 1916), 145,000 Italians from Littoral and South-Tyrol (1915), at least 70,000 Slovenians and 7,000 Croatians from the Littoral (1915) and 90,000 Bosnians (1914). It is estimated that by mid-1915 1.1 million people had sought refuge in the central regions of the Empire. The great majority of the evacuees had been amassed in the five central regions of the Austrian half of the Empire (Upper Austria, Lower Austria, Bohemia, Moravia, Styria). In some cases, well-to-do refugees decided to remain in the “war zone”, living without state subventions. Only a small part of the refugees found refuge in Hungary: about 30,000 Italian-speaking refugees who had been evacuated from the Littoral were allocated to Hungary during the summer of 1915 to avoid overpopulation in Austria, and at least 30,000 Jewish refugees from Bukovina and Galicia fled to Hungary through the Carpathians.

The reasons for displacement coincided only in some cases with imminent military danger or humanitarian reasons, and rather reflected the military’s fear about the loyalty of populations living in border areas. The Ruthenian and Italian ruling classes were, for example, interned in Styria and Upper Austria as political suspects; at the same time, the evacuation of Ukrainian-speaking refugees was accompanied by thousands of summary executions and violence perpetrated by the Austrian army, which feared espionage. To sum up, the internment measures affected about 6,500 Ruthenians, 700 Poles (both concentrated in the internment camp of Thalerhof, Styria), 4,500 Italians (concentrated in the internment camp of Katzenau, Upper Austria and Wagna, Styria) and some Slovenians, Croatians and Romenians, scattered in numerous Internierungsstationen built in Lower Austria. Bosnian Serb political suspects were sent to the camps at Arad, Neszider and Gyöngyös in Hungary.

Political suspects were treated like enemy aliens and separated from refugees in camps or settlement areas. However, the fears of the military about the loyalty of peoples living in the border regions caused massive evacuations of civilians and worsened the quality of the assistance.

Control and Refugee Camps↑

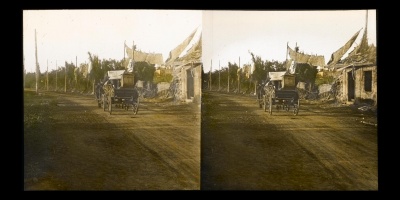

The ways in which people fled and were expelled from border regions complicated their accommodation in the interior: the military did not inform the Ministry of the Interior of evacuation from localities, journeys were made on cattle wagons and evacuations were carried out in just a few hours, very often in situations of open violence and pillaging. The result was extremely impoverished refugees, evacuated without any belongings or food.

In September 1914, the Austrian Ministry of the Interior decided to create sorting stations along the railway lines and resolved to accommodate a considerable number of refugees in camps. These were urban engineering systems that addressed multiple functions. They prevented the refugees from coming into contact with the local population in environments in which they were poorly accepted, they allowed for greater control of the displaced people and made it easier to achieve economies of scale in the food and clothing supply systems, ensuring that, within reasonable timescales schools, health and religious services could be set up for the use of the evacuees.

Refugee camps for Jews were created in Moravia at Nikolsburg, Gaya, Phorlitz (21,000 inmates) and in Bohemia at Deutsch Brod (20,000 inmates); other camps for Ruthenians were built at Gmünd in Lower Austria (27,000 inmates), Wolfsberg and St. Andrä in Carinthia (7,000 inmates); for Poles camps were created at Chotzen in Bohemia (12,500 inmates) and at Wagna, in Styria (25,000 inmates, until May 1915); for Italians refugee camps were built at Pottendorf (6,500 inmates) and Mittendorf in Lower Austria (12,000 inmates), at Braunau am Inn in Upper Austria (8,000 inmates) and at Wagna, in Styria (25,000 inmates); lastly, camps were set up for Slovenians at Steinklamm and Bruck an der Leitha in Lower Austria (5,500 inmates) and for Croatians at Gmünd in Lower Austria.

The rest of the refugees were brought to small villages, whose inhabitants spoke what was, to them, a foreign language. Here, they accounted for no more than two percent of the local population, were subject to strict controls and implicitly forced to work to survive, since the state subsidy for refugees was insufficient for them to live on. Moreover, those who refused a job offer could be dispatched to the concentration camps, where living conditions were even worse.

The Hungarian Ministry of the Interior refused at first to subsidize Austrian refugees who had sought shelter in Hungary. Therefore, those refugees were subsidized by the Austrian government, rapidly repatriated or resettled in Austrian regions. Only wealthy refugees who were living on their own means remained in Hungary, most of them Jewish refugees who fled from Galicia and Bukovina through the Carpathians.

Growing Hostility↑

The Austrian Ministry of Interior made great financial effort to improve the refugees’ living conditions, often helped by private welfare associations. Nevertheless, the displaced populations lived for years below the subsistence level. Living conditions inside the refugee camps, which housed about 130,000 inmates, were unbearable: in some cases the mortality rate was forty times higher than the pre-war level. Moreover, the refugees shared the feeling of being treated like prisoners. For example at Chotzen between December 1915 and March 1916 an average of 293 people a month died out of the 12,500 residents in the camp. Similar figures in the winter of 1915 to 1916 were also recorded at Steinklamm (274 deaths in December 2015 amongst the 5,000 evacuees) and Gmünd, where a peak was reached of 1,500 deaths in November 1915 amongst the 26,000 residents. The sensation of death that pervaded the camp was heightened by the poor quality, low-nutrient food (1,600 calories a day on average) and life in the communal huts.

There was also a similar trend in villages: although in Bohemia and Moravia the local communities in some cases established refugee relief institutions, living together was problematic because of national and religious prejudices. The situation of Vienna is a good case study: the Jews who fled there were gradually expelled because they were not generally accepted. Moreover, the refugees slowly became competitors in the labour market and unwanted guests, and this emerged clearly when the lack of food and goods became an everyday issue in the interior of the monarchy.

Repatriation and Exclusion↑

After the re-conquest of Galicia and the invasion of the Veneto, the authorities organised repatriation plans, with the aim of limiting social tension in the interior. The local communities used this legal loophole to expel as many refugees as possible from hosting communities, often resorting to violence and cutting off the payment of subsidies. In short, there was a breakdown in civil co-existence between hosts and refugees.

More than 300,000 refugees were still in the interior at the end of the war. This meant that after the armistice, the Austrian state no longer considered them as citizens of the new Austrian Republic. The same happened to those who were still in Czechoslovakia. Some new national states born after the fall of the Habsburg Monarchy took responsibility for many of them and organized a number of repatriation schemes, which came to end in spring 1919. This was the case for Italians and Slovenians. Jewish refugees living in the territory of the Austrian Republic instead became an internal problem since they decided to remain there to avoid the pogroms and the battles that broke out in 1918 and 1919 in Ukraine and Poland.

As a consequence, the presence of Jewish refugees in Vienna became an important issue of domestic policy in the 1920s in Austria. The refugees still residing in Czechoslovakia at the end of 1918 were partly expelled and partly forcefully repatriated in a short time. Those who had found shelter in Hungary were almost completely repatriated after 1918. The element that connects the three cases is the restrictive policies towards refugees after the war.

Summing up, the Habsburg citizens who experienced being evacuated to the Hinterland of the Empire saw an astonishingly rapid decline in their confidence in a state that proved itself incapable of guaranteeing their subsistence after evacuating them. Moreover, the lower state authorities began to expel refugees from the displacement areas as early as 1917 and the Ministry of the Interior refused, after November 1918, to subsidize the refugees still in Austria, by excluding them from Austrian citizenship.

Francesco Frizzera, Katholische Universität Eichstätt-Ingolstadt

Section Editor: Tamara Scheer

Selected Bibliography

- Hoffmann-Holter, Beatrix: 'Abreisendmachung'. Jüdische Kriegsflüchtlinge in Wien 1914 bis 1923, Vienna et al. 1995: Böhlau.

- Klein-Pejšová, Rebekah: Beyond the 'infamous concentration camps of the old monarchy'. Jewish refugee policy from wartime Austria-Hungary to interwar Czechoslovakia, in: Austrian History Yearbook 45, 2014, pp. 150-166.

- Kuprian, Hermann: Flüchtlinge, Evakuierte und die staatliche Fürsorge, in: Eisterer, Klaus / Steiniger, Rolf (eds.): Tirol und der erste Weltkrieg, Innsbruck; Vienna 1995: Österreichischer Studienverlag, pp. 277-305.

- Mentzel, Walter: Welkriegsflüchtlinge in Cisleithanien 1914-1918, in: Heiss, Gernot / Rathkolb, Oliver (eds.): Asylland wider Willen. Flüchtlinge in Österreich im europäischer Kontext seit 1914, Vienna 1996: Verlag Jugend und Volk, pp. 17-44.

- Thorpe, Julie: Displacing empire. Refugee welfare, national activism and state legitimacy in Austria-Hungary in the First World War, in: Panayi, Panikos / Virdee, Pippa (eds.): Refugees and the end of empire. Imperial collapse and forced migration in the twentieth century, Houndmills; New York 2011: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 102-126.