Introduction↑

In the days after Britain’s declaration of war on Germany on 4 August 1914 and the New Zealand government’s proclamation of its full support for Britain, the country’s major newspapers reported on scenes of patriotic crowds cheering in the streets. Many people gathered outside press offices, eagerly awaiting more information. Given New Zealand’s location in the South Pacific, far removed from the main theatres of the First World War, newspapers were crucial in bringing war news to readers on the home front. Readers avidly consumed the papers, often in freely accessible library reading rooms, and appropriated them in their own ways, forming distinct yet overlapping readerships at home and at the front. War coverage in the country’s mainstream press – predominantly justifying New Zealand’s contribution in terms of loyalty and duty to the British Empire and encouraging enlistment – has led to a popular understanding that New Zealand’s population as a whole responded enthusiastically. However, the press also reflected many cautious and solemn voices, and critical opinions grew louder from 1916 onwards, especially in relation to conscription and working-class issues.

New Zealand’s Press Landscape by 1914↑

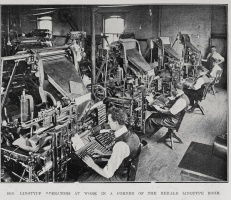

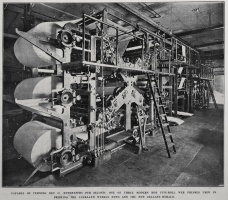

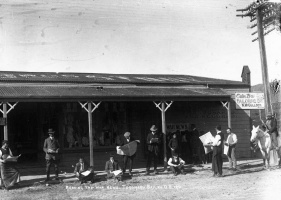

By the 1910s, a rich and diverse press landscape served the largely literate population of Pākehā (European) New Zealanders in urban and rural areas, reflecting a range of political, religious, and ethnic views and addressing at times overlapping national, regional, or local readerships. A small number of publications in Te Reo Māori specifically addressed Māori readers, with literacy rates among Māori in both languages also reaching substantial figures.[1] In 1914, the register of newspapers in New Zealand listed 233 publications, with sixty-three of these published daily, fifty-nine published two or three times a week, sixty-four published weekly, and thirty-nine titles monthly, the vast majority published in English.[2] This impressive number of titles, in a country with a population of just over 1 million, provided local, national, and international news, sustained local economies by giving space to advertisements and business announcements, and provided a platform for many political and ideological debates carried out in editorials and letters to the editor.

Reporting of international news in New Zealand was relatively uniform, even if editorial commentary could vary widely. Major national papers employed international correspondents, who filed reports directly to the editorial offices from overseas. However, the long time it took mail to reach the country made this system extremely impractical in times of urgency. Since the late 1870s, the international telegraph network connected New Zealand to global flows of information, but the cost of transmitting longer news items via this technology was prohibitive for individual papers. As a result, most international news printed in New Zealand filtered through press syndicates and associations, to which newspapers subscribed, predominantly the United Press Association, established in 1879.[3] This system was still in place in 1914. As Ian Grant notes, many New Zealand dailies “invariably carried columns of the same overseas news” or reprinted the same extracts from papers elsewhere, especially major Australian newspapers.[4]

A “Gentlemen’s Agreement” and Press Censorship↑

When the First World War broke out, New Zealanders learned the news via newspapers. People gathered outside newspaper offices to find out more, morning papers printed extra editions at night, and papers increased print runs, as for example in the Taranaki region where “runners distributed a thousand Taranaki Herald extras”.[5] While newspapers reported on enthusiastic and patriotic crowds celebrating the war news in public spaces, recent scholarship has convincingly shown that the public was more ambivalent about New Zealand’s participation in the war and that the country’s press reflected a range of views.[6] The majority of editorials expressed a sense of realism about the public and private costs of war and most commonly framed support as “an opportunity to show devotion to Britain” rather than as enthusiasm for war.[7]

In the initial few weeks and months after the outbreak of war, the majority of the country’s mainstream papers expressed little criticism of the government or questioned the need to send New Zealand troops in support of the British Empire. A “gentlemen’s agreement” between the government and the press, based on a hastily sent government circular on 7 August 1914 and preceding more detailed formal censorship regulations, meant that sensitive military information, especially about the movement of troops and naval vessels, was largely kept out of newspaper pages.[8] Yet, almost immediately, the government’s desire to keep military information secret clashed with the commercial imperative of newspapers, keen to attract larger circulation numbers by breaking stories of public interest. On 10 August 1914, the Christchurch paper the Sun controversially reported on military preparations for the occupation of Samoa by New Zealand troops, which drew the ire not only of the government but also of other newspaper editors, expressing anger about the commercial advantage the Sun had over them by ignoring the agreement.[9]

Such instances made it apparent that censorship of news, as well as private mail, had to be formalised quickly. In early November 1914, the government issued the first of a series of regulations and circulars, formalising censorship of the press, which reached as far as prohibiting the publication of anything that could be deemed discouraging enlistment of new troops or seen as “inciting disaffection from the government, or likely [to] incite violence”.[10] Subsequent legislation reached even further, prohibiting any criticism of the government or “generating hostility between employers and workers.”[11] Increasingly, editors voiced criticism of censorship regulations, seen as arbitrary, especially when the government withheld information that imperial government censors had already passed. The practical effect of receiving “cable news” from Britain-based press associations meant that international news printed in New Zealand had already been censored at the point of its gathering; often, it had even undergone a second round of censorship at the point of regional cable distribution in Australia. This double if not triple censorship of news proved to be a controversial topic between New Zealand press proprietors and the government throughout the war.

Because of increasingly complex censorship regulations, news was often “seriously delayed, severely truncated, or distorted to the point of confusion”.[12] When New Zealand troops landed at Gallipoli, the government withheld all information about the manoeuvre and papers could only report on the events after Australian newspapers, giving full details of the landing, had reached New Zealand shores.[13] The government’s approach to policing censorship regulations, on the other hand, remained arbitrary: very few mainstream papers faced prosecution when breaching regulations, and in reality, editors were continually weighing the risks of facing court with their own commercial interests.[14]

Newspapers in Everyday Life and Women Readers↑

During the war, newspapers were crucial for New Zealanders to access any kind of information about the conflict, however censored. While many readers purchased their own copies at newsstands, public libraries, which were widespread in New Zealand, also offered access to a large selection of domestic and international newspapers and periodicals in free reading rooms, including many Australian, British and North American publications. Increasing numbers of people made use of these offerings, a sign that the public was eager for news. In the country’s largest city, Auckland, the chief librarian commented that “the increase in the newspaper room is certainly due to the war, which has caused people to seek additional news from the large number of British newspapers in the newspaper room”.[15] In Timaru, a rural service town in the province of South Canterbury with a population of just under 11,000 residents, the librarian recorded close to 8,000 visits to the newspaper room during August 1914, increasing to 8,500 in the following months – a significant increase from previous numbers.[16] In Dunedin, the average daily attendance of the Public Library in September 1914 was recorded as 671, an equally impressive number, while in Wellington reports indicated that “the news room is always well filled”.[17] Responding to demand, libraries subscribed to specific war-related papers. For instance, the Timaru Public Library offered its users the British magazine T.P.’s Journal of Great Deeds of the Great War, published from October 1914 to October 1916 by Irish Nationalist and British Member of Parliament T.P. O’Connor (1848-1929), and, after the armistice, added the Australian weekly The Soldier: At Home and Abroad, a publication of the Returned Soldiers’ Association, to its reading room.[18]

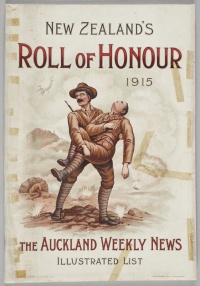

As the war progressed, casualty lists became a prominent feature of newspapers and a potent reminder of the cost of war. The Otago Witness and the Auckland Weekly News ran regular pages with “studio portraits of the dead, wounded or missing”, the latter even publishing a commemorative edition of 104 pages, with 4,000 images of killed or injured soldiers, at the end of 1915.[19] These lists of names and portraits of killed soldiers were often “the closest the New Zealand public came to visually confronting the loss of their young men”, constituting “immediate acts of public mourning in the absence of bodies.”[20] The Timaru librarian reported that patrons began to cut out photographs of newly enlisted or killed soldiers, presumably to keep as visual memory and personal mementos – a moving testimony to the power and significance of print during wartime.[21]

Newspapers reported on developments at the front and they discussed the consequences of war on New Zealand society, at times addressing distinct readerships. How women could contribute to the war effort, including as part of the paid workforce, was an issue of particular concern to women readers. The “women in print” column of the Wellington Evening Post constantly highlighted opportunities for women’s work and for charitable activities aligned with its middle-class readership’s values of domesticity and respectability: knitting, baking, packing parcels for soldiers, and fundraising in various ways. In addition the Evening Post column framed women’s war effort in the language of sacrifice – mothers sacrificing their sons or young women sacrificing home comforts and fashion by being thrifty – which allowed women to have a sense of making a real and tangible contribution.[22] Above all, even just reading the column and reading about women’s contributions to the war was one way of participating in the war.

Concerns about the appropriateness and nature of women’s work stretched into the immediate post-war period, coloured by the realities of the drawn out process of bringing demobilised soldiers back to New Zealand.[23] During the First World War, the Evening Post carefully avoided suggestions of gender transgressions, stressing that women’s incursions into male spheres of employment were temporary.[24] Yet, given that women were still needed to fill many professional roles well into 1919, women’s columns in the Evening Post and other New Zealand papers continued to encourage “working women” to pursue “their professional lives”, offering examples of successful careers and promoting professional development opportunities, vocational training, and tertiary education open to women.[25] These columns also offered women readers ways to be politically informed and active, commenting on a wide range of domestic and international issues including women’s enfranchisement in Britain and the USA and the newly legislated right for New Zealand women to stand for Parliament.[26]

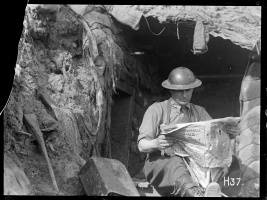

Distant Readerships – Soldiers at the Front↑

Many copies of New Zealand newspapers found their way to New Zealand soldiers at the front or in camp, sent amongst the millions of letters from relatives and friends. Soldiers could also access New Zealand papers in the reading rooms set up in training camps and near the front lines by the YMCA, the Red Cross Society, or the Salvation Army.[27] The New Zealand Club in London, offering food, accommodation and a space for soldiers to socialise while on leave, also stocked most New Zealand newspapers.

Like domestic readers, soldiers looked to papers for war news, even if they increasingly viewed newspaper coverage with scepticism and incredulity, as their own reality did not match with press reports. In a detailed letter describing his horrific experiences at Passchendaele, Private Leonard Hart (1894-1973) cautioned his family to “not believe our lying press”, which would no doubt distort facts to shore up support for the war. In an earlier letter recalling his experiences at Gallipoli, he declared, “Much that I have read in the papers about things alleged to have happened on the Peninsula are absolute nonsense”.[28] Soldiers also commented on the fictitious or inaccurate nature of soldiers’ letters reprinted in New Zealand papers. Private Francis Leslie Sapsford (1889-1915), writing from camp in Zeitoun, Egypt, told his mother: “Firstly, for the Lords sake don’t let any more of my letters get in the papers or I won’t write any more”. He explained, “If you only knew what lies have been written by some of the fellows here and published in the New Zealand papers, they have been so awful, that anybody’s letters, whether true or not, are the joke of the camp”.[29]

If not for war news, soldiers cherished New Zealand papers for their local content, allowing them to imaginatively and emotionally remain part of home front communities and to temporarily escape from the realities of war. Front pages continued to display local advertisements, announcements of events, and job vacancies and domestic coverage dominated much of the press. Many soldiers wrote of receiving New Zealand papers or explicitly asked correspondents for them, stressing their interest in news from home.[30] Peter Howden (1885-1917), for instance, a second lieutenant with the New Zealand Expeditionary Force who saw action in Belgium and France and died in October 1917, regularly noted that his family had sent him copies of the Christchurch Weekly Press and that he had seen the Auckland Weekly News while on leave in London.[31] Soldiers often shared papers amongst each other, further extending readership. Sergeant Harry Fulcher (1894-1917) wrote to his mother in September 1917, a month before being killed in action: “I like to get an Auckland Star, it always gives all the news of Auckland”, adding later that he often handed “it over to some other Auckland boys”.[32] Private William Malcolm (1897-1971) of Enfeld, Otago noted that “An Otago Witness is as common as an Auckland Weekly with this company now”, mostly due to several of his family members sending the paper.[33]

At times, newsprint crossed with personal worlds. In March 1917, Howden wrote of his joy in seeing his son’s birth announcement in the Evening Post, sent with his wife Edith Rhoda’s (1893-1959) loving letters. Private Francis Leslie Gordon Jolly (1889-1963) of the Canterbury Battalion remembered a day at Gallipoli when the New Zealand mail arrived, bringing him “one of the ‘Weekly Presses’ to while away the time” while his friend Ted “had a copy of the daily Lyttelton Times”. Ted, Lance Corporal Edward Douglas Wilson (1881-1915), was killed in action and Jolly ended his recollections: “His youngest, Jimmy, had done some scrawling on it and Mrs Wilson had put an explanatory memo underneath. Jimmy says ‘Tell Daddy to come home at once.’ My God-father, that rings in my ears today”.[34] In these moving instances of the hardships of family separation, newsprint was one means that kept emotional connections alive, even if just in the form of the mundane announcement of a birth or as the writing surface for personal messages.

Voices of Dissent – Newspapers with Working-Class and Irish Readerships↑

While the majority of New Zealand’s mainstream press was relatively compliant with government policies and supported the war effort, a number of left-leaning and socialist papers with working-class readerships voiced dissent. Truth, an Australian-owned “radical, stridently anti-war weekly”, published from Wellington since 1906, and, according to its by-line, “the paper with the largest circulation throughout the Dominion”, reacted to the war news by printing a scathingly anti-war poem prominently on its front page.[35] The paper continued to print anti-war caricatures and commentary throughout the war, in line with its long established anti-military views, and its editors “worked to position” the paper as a mouthpiece and “tireless champion of the ordinary Kiwi […] soldier”.[36]

Equally critical of the government and expressing staunch anti-war views were the Maoriland Worker and Green Ray. The Maoriland Worker, launched as a monthly in 1910 and published from Wellington as a weekly from 1911, represented the views of the “Red” Federation of Labour and had a wide reach across the country with a circulation number of 10,000 by the beginning of 1913.[37] Its war-time editor Harry Holland (1868-1933) would become an elected member of Parliament in 1918 and, a year later, the leader of the recently formed Labour Party. Focused on workers’ issues and supporting international socialism, the paper was fiercely pacifist and “saw no glory in participation” in the war.[38] Commentary in the first few issues after the outbreak of war warned that workers would shoulder the majority of the costs and sacrifices demanded by war and condemned “the frantic jingoism displayed in some [Labour] quarters” and the “mad militarism now indulged in”.[39]

Now less well-known, the Dunedin-based monthly the Green Ray, first published in late 1916 and loosely affiliated with the Dunedin Irish Club, linked its socialist tendencies with Irish issues. Its editor Thomas Padraic Cummins (1885-?), an “itinerant Irish journalist”, had previously been the Dunedin correspondent for Truth.[40] The Green Ray was important in bringing a specific ethnic voice to New Zealand’s print landscape, highlighting the many ties of migration that continued to shape New Zealand society. However, the paper did not represent the views of all Irish in the country. In the wake of the 1916 Dublin Easter Rising, and the overreaction of the British including the public execution of rebel leaders, sections of New Zealand’s Irish population sympathetic with Sinn Féin became increasingly critical of the British imperial government and of New Zealand’s role in the war.[41] The Green Ray was the publicity organ of these dissenting Irish.

All three papers became especially outspoken when the New Zealand government first aired the idea of compulsory military service in early 1916 and then introduced conscription of military-age, able-bodied men in August 1916 as voluntary enlistments began to dwindle.[42]Truth, the Maoriland Worker, and Green Ray vehemently opposed conscription, framing the issue as another example of the exploitation of workers. Several of Green Ray’s contributors worked underground after being drafted and the paper frequently reported “the efforts of conscientious objectors to evade the authorities […] with approbation.”[43] All three papers exposed and condemned the government’s heavy-handed approach to dealing with conscientious objectors – those objecting to military service due to religious or pacifist convictions –, which eventually saw a group of fourteen men, including the later well-known Archibald Baxter (1881-1970), deported to military camps in England and to front lines in Europe. Truth and Green Ray published letters from Baxter, which described his and his fellow prisoners’ ordeals in camp and at the front.[44]Truth and the Maoriland Worker evaded prosecution by co-operating with the chief censor and framing government criticism as highlighting “the difficulties faced by the average soldier”.[45] The police monitored Green Ray from mid-1917, closing it down in June 1918 for seditious comment, and sentencing both the paper’s editor and manager to eleven months in jail with hard labour.[46]

Conclusion↑

New Zealand’s geographical position in the South Pacific, far removed from the battlefields, accentuated the significance, as well as the difficulties, of newspapers for bringing war news to home front readers, even if military intelligence was censored. Through their consumption of papers, often accessed in free library reading rooms, New Zealanders were well informed of geopolitical events. However, readers used newspapers for more than just information. Library users cut out soldier portraits in casualty lists in acts of public and private mourning; women readers found ways of participating in the war effort within the weekly ladies’ columns in major national papers; and soldiers at the front eagerly read local New Zealand news to stay connected to home front communities and pre-war lives.

Like mainstream papers in Britain and other British dominions, New Zealand’s press was largely supportive of the country’s participation in the war and newspapers played an essential role in sustaining a public mood supportive of the war effort. Yet, debates about national and local issues in newspaper pages highlighted contentious issues, especially concerning the introduction of conscription in August 1916 and the arbitrary censorship regulations to which the press had to conform. A number of publications aligned with socialist, worker, and Irish readerships voiced criticism of the war and the government’s unquestioning support of it. Such critical voices grew louder as time went on.

Susann Liebich, Universität Heidelberg

Section Editor: Kate Hunter

Notes

- ↑ The focus of this short article is on English-language newspapers only. On literacy, see Wevers, Lydia: Literacy and Reading, in: Griffith, Penny / Harvey, Ross / Maslen, Keith (eds.): Book & Print in New Zealand. A Guide to Print Culture in Aotearoa, Wellington 1997, online: http://nzetc.victoria.ac.nz/tm/scholarly/tei-GriBook-_div2-N12DC1.html (retrieved: 21 May 2019). On newspapers in Te Reo Māori, see Paterson, Lachy: Colonial Discourses. Niupepa Māori 1855-1863, Dunedin 2006; McRae, Jane: ‘Ki nga pito e wha o te ao nei’. Maori Publishing and Writing for Nineteenth-Century Maori-Language Newspapers, in: Alcorn Baron, Sabrina / Lindquist, Eric N. / Shevlin, Eleanor F. (eds.): Agent of Change. Print Culture Studies After Elizabeth L. Eisenstein, Amherst 2007, pp. 287-299.

- ↑ New Zealand Official Yearbook, 1914, online: https://www3.stats.govt.nz/New_Zealand_Official_Yearbooks/1914/NZOYB_1914.html (retrieved: 14 May 2019).

- ↑ Harvey, Ross: Newspapers, in: Griffiths / Harvey / Maslen (eds.), Book 1997, online: http://nzetc.victoria.ac.nz/tm/scholarly/tei-GriBook.html (retrieved: 21 May 2019).

- ↑ Grant, Ian: The News in New Zealand Newspapers During World War One, in: Turnbull Library Record 46/1 (2014), p. 27.

- ↑ Hucker, Graham: ‘The Great Wave of Enthusiasm’. New Zealand Reactions to the First World War in August 1914 – a Re-Assessment, in: The New Zealand Journal of History 43/1 (2009), p. 65.

- ↑ Hucker, The Great Wave 2009; McGibbon, Ian: The Shaping of New Zealand’s War Effort, August–October 1914, in: Crawford, John / McGibbon, Ian (eds.): New Zealand’s Great War. New Zealand, the Allies & the First World War, Auckland 2007, p. 51.

- ↑ Hucker,The Great Wave 2009, p. 68.

- ↑ John Anderson refers to an “honourable agreement” between newspaper editors and the government, see Anderson, John: Military Censorship in World War I and Its Use and Abuse in New Zealand, Thesis, Victoria University College 1952, p. 169.

- ↑ Ibid.; Grant, News 2014, p. 28.

- ↑ Fenton, Damien: New Zealand and the First World War, 1914-1919, Auckland 2013, p. 4; Anderson, Military Censorship 1952, chapter 6; Grant, News in New Zealand 2014, pp. 29-30.

- ↑ Fenton, New Zealand 2013, p. 41.

- ↑ Grant, News in New Zealand 2014, p. 30.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 30-31.

- ↑ Anderson, Military Censorship 1952, p. 210.

- ↑ Reading in War Time, in: Auckland Star, 2 August 1915, p. 2.

- ↑ Timaru Public Library, Library Reports for August, September and October 1914.

- ↑ Otago Daily Times, 22 September 1914, p. 10; Books for the Year. What the Public Read, in: Evening Post, 29 December 1915, p. 8.

- ↑ Timaru Public Library, Library Report for February 1915 and March 1919.

- ↑ Callister, Sandy: The Face of War: New Zealand's Great War Photography, Auckland 2008, p. 75.

- ↑ Callister, The Face of War 2008, pp. 75, 79.

- ↑ Timaru Public Library, Library Report for January 1916.

- ↑ Bowyer, Elizabeth: Sacrifice, Society and Style. An Analysis of the Evening’s Post ‘Women in Print’ Column During the First World War, Thesis, Victoria University of Wellington 2018, chapter 2.

- ↑ Ward, Emma: ‘Why Are these Old Fogeys So Frightened Of Us Women?’ Women’s Newspaper Columns and the Exploitation of the ‘Open Window’ in Post-War New Zealand, November 1918 – November 1920, Thesis, Victoria University of Wellington 2018, p. 7.

- ↑ Bowyer, Sacrifice, Society and Style 2018, pp. 25-26.

- ↑ Ward, Why Are these Old Fogeys 2018, p. 7.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 21.

- ↑ Keenan, Ria: On the Triangle Trail. The New Zealand YMCA and the Great War, in: Crawford / McGibbon (eds.), New Zealand’s Great War 2007, p. 357.

- ↑ Letters to his parents and sister Connie, dated 1 January 1916 and 19 October 1917, in: Phillips, Jock / Boyack, Nicholas / Malone, E.P. (eds.): The Great Adventure. New Zealand Soldiers Describe the First World War, Wellington 1988, pp. 136, 150.

- ↑ Letter to his mother, 8 April 1915, in: Harper, Glyn (ed.): Letters from the Battlefield. New Zealand Soldiers Write Home, 1914-18, Auckland 2001, p. 48.

- ↑ See, for instance, Sapper Daniel Kilpatrick asking his sister Lil to "[s]end an Auckland Weekly every week if you don’t mind", 9 September 1915, in: Harper, Glyn (ed.): Letters from Gallipoli. New Zealand Soldiers Write Home, Auckland 2011, p. 282.

- ↑ Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, Peter Howden papers, MS-Papers-1504-3 (letters dated 24 June 1917, 26 June 1917, 4 July 1917), MS-Papers-1504-04 (letters dated 8 July 1917, 7 September 1917).

- ↑ Letters dated 7 and 14 September 1917, in: Harper (ed.), Letters from the Battlefield 2001, pp. 110-111.

- ↑ Letter to his sister Margaret, 7 July 1918, in: McKenzie, Dorothy / Malcolm, Lindsay (eds.): Boots, Belts, Rifle & Pack. A New Zealand Soldier at War, 1917-1919, Dunedin 1992, p. 111.

- ↑ Letter to the Wilson family, 17 December 1915, in: Harper (ed.), Letters from Gallipoli 2011, p. 264.

- ↑ Yska, Redmer: The First World War and Truth, in: Ferrall, Charles / Ricketts, Harry (eds.): How We Remember. New Zealand and the First World War, Wellington 2014, p. 148. Noyes, Alfred: The War Makers, in: Truth, 8 August 1914, p. 1.

- ↑ Yska, The First World War 2014, p. 151.

- ↑ The Maoriland Worker. Background, online: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/maoriland-worker (retrieved: 16 July 2019).

- ↑ Grant, The News in New Zealand 2014, p. 26.

- ↑ The Jingo Spirit, in: The Maoriland Worker, 12 August 1914, p. 4.

- ↑ Brosnahan, Sean: ‘Shaming The Shoneens’. The Green Ray and The Maoriland Irish Society in Dunedin, 1916-22, in: Fraser, Lyndon (ed.): A Distant Shore. Irish Migration and New Zealand Settlement, Dunedin 2000, p. 123.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 120.

- ↑ Fenton, New Zealand 2013, p. 34.

- ↑ Brosnahan, ‘Shaming the Shoneens’ 2000, p. 123.

- ↑ Yska, The First World War 2014, p. 158. Brosnahan, Sean: ‘Shaming The Shoneens’. The Green Ray and The Maoriland Irish Society in Dunedin, 1916-22, longer draft of subsequently published chapter, online: https://ceannfine.files.wordpress.com/2014/01/shamings.pdf (retrieved 17 October 2019).

- ↑ Yska, The First World War 2014, p. 152.

- ↑ Brosnahan, ‘Shaming the Shoneens’ 2000, pp. 128-129.

Selected Bibliography

- Anderson, John: Military censorship in World War I. Its use and abuse in New Zealand, thesis, Wellington 1952: Victoria University of Wellington.

- Ballantyne, Tony: Thinking local. Knowledge, sociability and community in Gore's intellectual life, 1875-1914, in: The New Zealand Journal of History 44/2, 2010, pp. 138-156.

- Bowyer, Elizabeth: Sacrifice, society and style. An analysis of the Evening’s Post ‘Women in Print’ column during the First World War, thesis, Wellington 2018: Victoria University of Wellington.

- Brosnahan, Sean: ‘Shaming the shoneens’. The Green Ray and the Maoriland Irish Society in Dunedin, 1916-22, in: Fraser, Lyndon (ed.): A distant shore. Irish migration and New Zealand settlement, Dunedin 2000: University of Otago Press, pp. 117-134.

- Grant, Ian F.: The news in New Zealand newspapers during World War One, in: Turnbull Library Record 46, 2014, pp. 25-39.

- Hucker, Graham: 'The great wave of enthusiasm.' New Zealand reactions to the First World War in August 1914 - A reassessment, in: The New Zealand Journal of History 43/1, 2009, pp. 59-75.

- Liebich, Susann: Connected readers. Reading practices and communities across the British Empire, c. 1890-1930, thesis, Wellington 2012: University of Wellington.

- Loveridge, Steven: Calls to arms. New Zealand society and commitment to the Great War, Wellington 2014: Victoria University Press.

- Potter, Simon J.: Communication and integration. The British and dominions press and the British world, c. 1876-1914, in: Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 31/2, 2003, pp. 190-206.

- Ward, Emma: 'Why are these old fogeys so frightened of us women?' Women’s newspaper columns and the exploitation of the ‘open window’ in post-war New Zealand, November 1918 - November 1920, thesis, Wellington 2018: Victoria University of Wellington.

- Yska, Redmer: The First World War and truth, in: Ferrall, Charles / Ricketts, Harry (eds.): How we remember. New Zealanders and the First World War, Wellington 2014: Victoria University Press, pp. 147-159.