Introduction↑

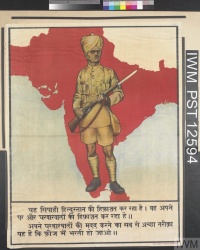

As Austrian artillery opened fire on the Serbian city of Belgrade in late July 1914, signaling the commencement of what would soon become a global conflict, the Zamindar, a newspaper in Lahore, India, saw the writing on the wall. The war would not be confined to Austria and Serbia, its editor Zafar Ali Khan (1873-1956) told his readers on July 30, “but will be a universal war in which all the great empires of Europe will be involved.”[1] A century after the outbreak of World War I, scholars today consider seriously the conflict’s global and imperial dynamics.[2] Among the belligerent powers, none drew more extensively on overseas colonial resources than Great Britain. Undivided India supplied money, materiel, and manpower. Between 1914 and 1918, 1.5 million Indians fought for the British Empire in the Indian Army. These men were deployed to three continents, belonging at any given time to one of the seven expeditionary forces India sent overseas during the war – some 89,000 of them as combatant soldiers to France and Belgium (Indian Expeditionary Force A, or IEFA); 34,000 combatants to East Africa (IEFB and IEFC); 327,000 to Mesopotamia (IEFD); 110,000 combatants to the Sinai and Palestine (IEFE and IEFF); 3,100 to Gallipoli (IEFG); and thousands more scattered to other theaters.[3]

A good deal of recent scholarship on India in World War I has explored what Indian soldiers said about the war in their letters home.[4] When we talk about the Indian press and Indian journalism during World War I, we are necessarily shifting away from a focus on peasant–warrior responses to the war in favor of the discourse of India’s elite—that of the colonizer and of the colonized.[5] India’s colonial rulers – the white, Anglo-Indian “sahibs” (colonial administrators, for example company men and their wives; members of the leisured classes) – wrote and published extensively on the war for an Anglo-Indian press. Members of the emerging Indian bourgeoisie – educated, urban “babus” belonging to the professional classes – also debated the war vigorously in a robust and well-established press industry.[6] It is this Indian press that will be discussed here.

Responses to the Outbreak of War and Recruitment Efforts↑

Indian readers in cities such as Calcutta (now Kolkata) in Bengal, or Lahore and Amritsar in Punjab, could choose from a number of newspapers in a variety of languages at the start of the war. In the 1870s, Bengal’s newly visible bourgeoisie had established important newspapers, such as the Amrita Bazar Patrika and The Bengalee. From the pages of these newspapers, India’s college-educated middle classes positioned themselves against India’s traditional ruling princes and the majority of Indians, the peasants, and the urban poor, by articulating a host of political reforms.[7] Punjab also boasted a thriving press industry at the turn of the century, with Lahore at the industry’s epicenter. In 1914, the city’s readers could choose from more than seventy titles, most of those in English, Urdu, or Gurmukhi. Amritsar offered close to thirty newspapers and periodicals, Rawalpindi had at least seven.[8] Most titles had a modest circulation of 1,000 copies. Some newspapers, such as the English-language Tribune, printed in Lahore, circulated 2,000 copies daily. Zamindar, also printed in Lahore, boasted a circulation of 15,000 Urdu-language copies. There was also a robust newspaper industry in the provinces of North West Frontier, Bombay, and Madras.[9] Bombay offered some 165 titles, most of those in the Marathi and Gujarati languages. In Madras, G. A. Natesan & Co. opened shop in 1900. Natesan’s monthly periodical, The Indian Review, enjoyed international acclaim. Each edition featured contributions in English on a range of topics at an annual subscription rate of Rs.5. Natesan’s Indian Review was “the moderate voice of modern India; representing the educated middle-classes, it was critical of discriminatory policies and argued for greater political autonomy but at the same time with a continuing loyalty towards the British Raj.”[10] The “extremists” also had their organs, such as Bal Gangadhar Tilak’s (1856-1920) two newspapers, Kesari and Mahratta.[11]

When war broke out in August 1914, India’s vernacular press rallied to the British standard. In Bombay, the Jam-e-Jamshad proclaimed, “This is the time when India should feel it to be her duty to show to the world – to England’s foes and allies alike – how greatly she is attached to her.”[12] The Bengalee (Calcutta) echoed, “Behind the serried ranks of one of the finest armies in the world, there stand the multitudinous peoples of India, ready to cooperate with the Government in the defense of the Empire.”[13] Suspending its usual repertoire of criticism of government policy, Indian newspapers encouraged self-censorship. “Our readers are perhaps aware that we had promised in our last [issue] to consider in our leader of to-day the remaining objections of Lord Curzon to the India Council Bill,” read The Observer (Lahore) in one August 1914 edition. “But we felt that, in the light of the knowledge that war between England and Germany had commenced and the first shot has been fired, we deem it a sacred duty . . . to cease discussing questions of a political hue, likely to embarrass and cause anxiety to the authorities out here.”[14] In Madras, G. A. Natesan (1873-1948) wrote in The Indian Review, “Our grievances, our rights, our privileges, our reforms and charters, we forget for the moment and we only remember our sacred and solemn obligation to the great power that has moulded our destinies hitherto and which is bound to lift us all onward to a better and prouder goal.”[15] Press responses such as these dovetailed with those of nationalist organizations such as the Indian National Congress, whose moderate members hoped that their support for the imperial war effort would endear their cause to the British, securing for India a greater stake in imperial governance in the postwar settlements.

There were a few notable instances of collaboration between India’s ruling “sahibs” and professional “babus” in wartime publishing endeavors. For example, a colonial war journal called Indian Ink, published in Calcutta by W. Thacker & Co., was funded by Anglo-Indian companies but included contributions by Indian writers. Another journal, the Indian Review War Book, issued in 1915 by G. A. Natesan & Co., likewise included essays about the war, written by Indians and Europeans. Indian Ink and the Indian Review War Book “reveal the existence of a highly complex relationship between war and colonialism rather than a simple narrative of either imperial loyalty or colonial exploitation.”[16] Sometimes, the wartime relationship between the Indian vernacular press and the Anglo-Indian press proved just as acrimonious as ever. Two Anglo-Indian newspapers in particular, The Englishman, and The Pioneer, had been provoking the ire of India’s vernacular press since the late 19th century.[17] When World War I began, K. N. Roy’s tri-weekly Panjabee (Lahore) called out The Pioneer for making “a stupid and senseless attack upon His Majesty’s Indian troops.” A September 1914 article in The Pioneer had said of Indian troops, “even when trained and led by British officers, a very small portion of them come up to the British standard. If they did the British would not be in India.” The Panjabee shot back, “The statement, which would have been unfortunate and untrue at all times, is specially impolitic and mischievous at a moment like this, when the whole of India is pulsating with feelings of loyalty and devotion to the British Throne and when so much depends upon the encouragement which the Indian troops both here and at the front receive.”[18]

For the Indian vernacular press, national honor, Indian manhood, and racial equality were all at stake in the war’s outcome. The question the Indian press asked in 1914 was not “would India support the war?” The question the press asked was “would Britain allow Indians to participate in it?”[19] Indian infantry and cavalry had been expressly barred from fighting a white enemy in the recent South African War (1899-1902). For this reason, the vernacular press applauded the deployment of Indian troops to France in 1914. “The employment of Indian troops in the present war is to be commended principally for the reason that it is a step towards the eventual obliteration of existing racial prejudice, so essential to India’s self-fulfillment as a nation and an integral part of the Empire,” the Panjabee (Lahore) offered in September 1914.[20] Service in the Indian Army was open only to a narrow stratum of the Indian peasantry, in accordance with the then contemporary theory of the “martial races.”[21] Some middle-class Indians lobbied for the right to join the army. “It must be remembered that Indians are divided into two distinct classes – the educated and the illiterate,” ran one article in the Prabhat (Lahore). “To pit the latter against German soldiers who are fighting with a spirit of patriotism is ridiculous. What Government should do is to enlist the services of educated Indians . . . [who would] be fit to meet Germans in the battlefield.”[22] Many in the Indian press also wanted to see the army make Indian officers eligible for the king’s commission. Army policy stipulated that only white soldiers could receive a king’s commission (they were called KCOs). Indians were eligible for viceroy’s commissions (called VCOs). An Indian could serve as an officer, in other words, but a viceroy’s commission ensured he was always subordinate to a white officer serving with a king’s commission.[23] To the Indian press, the VCO was a “badge of inferiority.”[24] In 1915, the Urdu Bulletin (Lahore) argued, “The enthusiasm, bravery and loyalty which Indian armies are displaying in Europe, Asia and Africa have no parallel. Surely these services should be rewarded by granting Indian officers their real rights and by raising them to commissioned ranks.”[25]

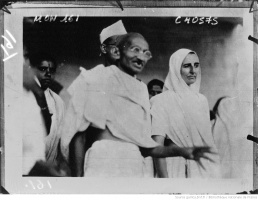

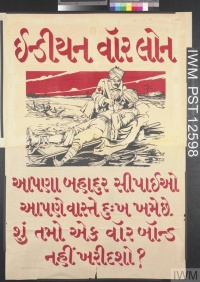

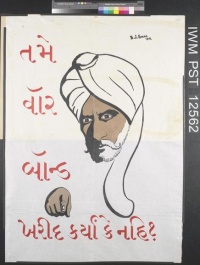

Throughout the war, the Indian vernacular press acted as a mouthpiece for army recruiting efforts. In March 1915, Siraj-ul-Akhbar (Jhelum) called attention to the “strange stories” circulating in the countryside, told by wounded soldiers returned from the front, “which conflict with the contents of official newspapers. They should be prohibited from telling anything about the war, as such rumours especially raise obstacles in the way of recruiting new men for the army.”[26] Among all the provinces in India that provided soldiers for the army, none furnished more soldiers than Punjab. By 1918, fully half of the combatants the Indian Army sent abroad were Punjabis.[27] Punjabis therefore had a special interest in army recruitment efforts. Military service functioned as much as a vehicle for regional prestige as it could for national prestige. “If we demand self-government, we should be prepared to sacrifice ourselves in defending the Empire,” ran an article in the Hindustan (Lahore).[28] When the Indian Army agreed in 1916 to raise a double company of 250 college-educated Punjabis, the Khalsa Samachar urged its Sikh readership in Amritsar: “It is hoped that educated Punjabis will readily respond to the call and maintain the honor of their province.”[29] When the German Army launched its March 1918 offensives on the Western Front, Prime Minister David Lloyd George (1863-1945) warned in a speech before the British parliament that the Allies had entered the “most critical” phase of the war.[30] In April, the viceroy held a three-day war conference in Delhi where delegates — including Mahatma Gandhi (1869-1948) — pledged to help secure 500,000 more Indian recruits for the army. In Ferozepore, Punjabi Bhain stated that “Indian women [should] help the Government in the defense of the country. They should urge their relations to go to the front and induce large numbers of men to come forward as recruits.”[31]

Censorship, Surveillance, and War News↑

Unlike many European or American newspapers that had staff at the front writing reports as events unfolded, the Indian press did not have dedicated personnel wiring home news from the frontlines. Indian newspapers were left to scavenge war news where they could, from the major syndicates like Reuters, from European newspapers, and from official reports and communiqués issued by the British government and the government of India. Indian journalists who wanted to provide their readers with reliable war news knew they were operating with something of a handicap. “True news can with difficulty be received from the seat of war and secondly whatever news is received is pruned by the official Press censor,” one newspaper, Akhbar-i-‘Am (Lahore) commented.[32] Reporting the war from this position could be especially trying when events were unfolding rapidly. “It is impossible to see any consistency in the war news which is officially published throughout the country,” lamented the Jhang Sial (Lahore) in October 1914. “Sometimes we hear of British successes, sometimes of their reverses. The ordinary man is thrown into a state of confusion. He is at a loss to know what to believe.”[33] Newspaper editors banded together into news agencies like the Punjabi War News Association to provide the vernacular press a clearinghouse of vetted war news.[34]

The appetite the Indian press displayed for reporting war news ebbed and flowed between the advent of the war in 1914 and the German armistice in November 1918. The war dominated the pages of newspapers in the conflict’s opening months. German atrocities in Belgium and Turkey’s declaration of war received notable mention. In 1915, Indian audiences read about the Dardanelles Campaign, submarine warfare in the Atlantic, the stalemate in France, and the mass murder of Armenians at the hands of the Turks. In Lahore, the Tribune reflected on the one-year anniversary of the outbreak of the war. “The last twelve months have brought home to humanity the grim fact that in the pursuit of her nefarious designs Germany has as little regard for the instincts of humanity as for the principles of warfare.” Praying for the success of Great Britain and its allies, the Tribune commented that 4 August 1915 marked “a day of thanksgiving that we are on the side of right and truth.”[35] Uprisings in Ireland and the Hedjaz made headlines in 1916. So did the Battle of Verdun. In 1917, Indian newspapers applauded the collapse of the tsar’s government as a victory for humanity. America’s entry into the war and the Indian Army’s capture of Baghdad in March and Jerusalem in December fueled optimism that the war might soon come to a successful conclusion. The Western Front dominated the news cycle in 1918. As the Allied offensive gained steady ground, the Khalsa Advocate told its readers in Amritsar, “The German bubble . . . is about to burst.” Everywhere German forces were collapsing under the weight of their combined enemies. “It is clear that the Allies are on the sure road to victory.”[36]

From the perspective of the government of India, the Indian press was not a thing to be ignored; it was to be recorded, studied, and censored.[37] The government of India’s Criminal Investigation Department conducted routine surveillance of the Indian vernacular press, issuing weekly reports on the tenor of the press, along with a collection of translated newspaper articles. As in Britain, where the 1914 Defence of the Realm Act banned reports that might undermine loyalty to the king or deter recruitment, the 1915 Defence of India Act empowered the government to shut down newspapers and arrest editors deemed guilty of spreading sedition. Zafar Ali Khan spent much of the war under house arrest and his newspaper, the Zamindar (Lahore), was in and out of print, per order of the state.[38] Some journalists seethed as they navigated the seemingly byzantine and arbitrary rules of a government in which they had no real say. The heavy-handed tactics of Punjab’s lieutenant-governor, Michael O’Dwyer (1864-1940), were the source of considerable resentment. In 1916, the Panjabee (Lahore) complained of “a hardening of the official attitude” of the state, “which is more surprising because the press all over the country has nobly responded to the call of duty and has eschewed much of the criticism in which it indulges in ordinary times.”[39]

In June 1916, when authorities in Madras, invoking the Press Act, placed the nationalist leader Annie Besant (1847-1933) under arrest for her activities involving the Home Rule League, the outcry from the Indian press was swift and unequivocal. “The innumerable meetings of protest held in almost all the principal mofussil stations in the Presidency of Madras and in the leading towns and cities of the country, and the unanimity with which the Indian Press – English and Vernacular – has pronounced itself on the step taken by the authorities in Madras, are strong evidences to show how the entire country views with concern the existence of the Press Act on the Statute Books,” Ganapathi Agraharam Natesan (1873-1948) observed in the June edition of The Indian Review. “It is no wonder that men of all shades of opinion and even journalists and publicists, who have had differences of opinion with Mrs. Annie Besant and who do not certainly see eye to eye with her on some important public questions and even disapprove of the tone of some of her writings and speeches, have banded themselves together to vigorously urge the repeal of the law, which is undoubtedly a standing menace to the liberty of Indian journalism.”[40] Later that month, the Indian Press Association organized an open-door meeting in Bombay to demand Besant’s release and the immediate repeal of the Press Act. Chaired by the editor of the Bombay Chronicle, Benjamin Guy Horniman (1873-1948), the meeting’s attendees unanimously approved a resolution, drafted by Gandhi, asking “that the Press in this country should enjoy the utmost liberty of expression, subject to the legal restraints of ordinary law, and of penalties inflicted only after proper trial and conviction.”[41]

The Press and Political Change↑

The future of India’s place within the empire inspired the most heated discussion and debate within the Indian press. Indian nationalists earnestly believed that India’s contributions to the imperial war effort would secure for India self-government and its own representative institutions modeled after those enjoyed by white Canadians or white Australians. In the Punjab, the Kisan offered for its readership in September 1917,

At war’s end, the Tribune (Lahore) claimed that India, “by her deeds and sacrifices made good her claim to an equality within the Empire.”[43] Excerpts like these serve as an important reminder that throughout the conflict, prevailing nationalist opinion held that India’s political future lay squarely within the larger fabric of the British Empire. G. A. Natesan editorialized in the November 1918 edition of The Indian Review,

In the winter of 1918 and 1919, all eyes turned to the peace talks in Paris, where the American President Woodrow Wilson (1856-1924) was preaching national self-determination. “The question now is to what extent is India going to benefit by the principles for which she gave her lives and treasure,” wrote Pandit M. M. Malaviya (1861-1946), an educator and wartime president of the Indian National Congress, in The Indian Review.[45] But in February, the Indian press shifted the focus from Paris to a frightening development in India.[46] That month, the government of India enacted the Rowlatt Bills, indefinitely suspending habeas corpus by extending the Defence of India Act into peacetime. Thenceforth, anyone charged with sedition would have to prove his or her innocence, rather than the state having to prove the guilt of the accused. The Indian press was unsparing in its criticism of the new laws. In Calcutta, Amrita Bazar Patrika said, in a February 1919 edition,

The Bombay Chronicle said that the Rowlatt Bills

In Amritsar, the Waqt published a cartoon depicting the secretary of state handing the “Order of Liberty” to India, when suddenly a black cobra, released from a basket by Sidney Rowlatt (1862-1945), bites India.[49]

From his home in Ahmedabad, Gandhi began organizing a campaign of nonviolent civil disobedience, or satyagraha, in defiance of British law, and a nationwide hartal, or general strike. Through late February and March 1919, the Indian press reprinted his satyagraha pledge and followed his nationwide speaking tour, one that took him from Bombay to Madras; from Tanjore to Nagapatnam.[50] The hartal began in Delhi on 30 March. It spread to cities throughout northern India in the weeks that followed. Indian Army soldiers, deployed by the government of India to contain things, fired on demonstrators in Delhi, Amritsar, Lahore, Ahmedabad, Calcutta, and Bombay. On 13 April, at the Jallianwala Bagh in Amritsar, General Reginald Dyer (1864-1927) ordered a detachment of Indian soldiers to fire into a large crowd of people, massacring 379 and wounding over 1,000.[51] In the months that followed, the Indian government and military orchestrated a ruthless crackdown on dissent in the vernacular press. In the Punjab, newspapers that had been outspoken in their criticism of the Rowlatt Bills and General Dyer’s actions at the Jallianwala Bagh were ordered to submit all materials to government censors for approval before going to press. Many simply suspended publication. The government tried the editors of the Tribune and the Partap before a Martial Law Commission, sentencing the former to two years’ imprisonment and the latter to eighteen months.[52] For many of those in India who had been loyal to the empire during the war, the government of India’s brutal postwar crackdown on dissent marked their decisive turning point away from the empire. For members of the Indian press, the decision of the Indian National Congress to adopt Gandhi’s policy of non-cooperation in 1920 exposed deep rifts and differences of opinion. G. A. Natesan, as harsh a critic of the government’s postwar crackdown as any, voiced his dismay at the direction he saw Indian politics going. “We feel strongly that the [non-cooperation] movement will defeat the very object it has in view;” he wrote in The Indian Review, “and that though started with the honest intention of being worked in a non-violent spirit it is likely to lead to violence.”[53] Natesan’s warning was prescient, for indeed the decades to come, although they ultimately led to the end of British colonial rule in India, would be among the most tumultuous in modern Indian history.

Andrew Tait Jarboe, Berklee College of Music

Section Editor: Santanu Das

Notes

- ↑ Jarboe, Andrew Tait: War News in India. The Punjabi Press During World War I, London et al. 2016, p. 1.

- ↑ See Jarboe, Andrew Tait / Fogarty, Richard (eds.): Empires in World War I. Shifting Frontiers and Imperial Dynamics in a Global Conflict, London 2014; Gerwarth, Robert / Manela, Erez (eds.): Empires at War, 1911-1923, Oxford 2014.

- ↑ See Roy, Kaushik: Indian Army and the First World War, 1914-18, Oxford 2018; Morton-Jack, George: Army of Empire. The Untold Story of the Indian Army in World War I, New York 2018; Morton-Jack, George: The Indian Army on the Western Front, Cambridge 2014; Basu, Shrabani: For King and Another Country. Indian Soldiers on the Western Front, 1914-18, London 2016; Kant, Vedica: “If I Die Here, Who Will Remember Me?” India and the First World War, New Delhi 2014.

- ↑ Singh, Gajendra: The Testimonies of Indian Soldiers and the Two World Wars. Between Self and Sepoy, London 2014; Omissi, David: Indian Voices of the Great War. Soldiers’ Letters, 1914–18, London 1999.

- ↑ Barrier, N. G. / Wallace, Paul: The Punjab Press, 1880-1905, East Lansing 1970; Barrier, N. G.: Banned. Controversial Literature and Political Control in British India, 1907-1947, Columbia 1974; Joshi, Sanjay: Fractured Modernity. Making of a Middle Class in Colonial North India, New Delhi 2001.

- ↑ Das, Santanu: Sepoys, Sahubs, and Babus. India, the Great War and Two Colonial Journals, in: Hammond, M. / Towheed, S. (eds.): Publishing in the First World War, London 2007, p. 63.

- ↑ Sinha, Mrinalini: Colonial Masculinity. The "Manly Englishman" and the "Effeminate Bengali" in the Late Nineteenth Century, Manchester 1995, p. 6.

- ↑ For extracts from the Punjab Newspaper Reports, see India Office Records IOR/L/R/5/195-201.

- ↑ North West Frontier Province Newspaper Reports, India Office Records IOR/L/R/5/89-95; Bombay Newspaper Reports, IOR/L/R/5/169-175; Madras Newspaper Reports, IOR/L/R/5/119-126.

- ↑ Das, Sepoys, Sahibs and Babus 2007, p. 70.

- ↑ Das, Santanu: India, Empire, and First World War Culture. Writings, Images, and Songs, Cambridge 2018, p. 51.

- ↑ MacMunn, G. F.: India and the War, London 1915, pp. 55-62.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Jarboe, War News 2016, pp. 20-21.

- ↑ India and the War, in: The Indian Review, volume 15, p. 600.

- ↑ Das, Sepoys, Sahibs and Babus 2007, p. 75.

- ↑ Sinha, Colonial Masculinity 1995, p. 80.

- ↑ Jarboe, War News 2016, pp. 32-33.

- ↑ Das, India, Empire and First World War Culture 2018, p. 51.

- ↑ Jarboe, War News 2016, p. 30.

- ↑ Streets-Salter, Heather: Martial Races. The Military, Race and Masculinity in British Imperial Culture, 1857-1914, New York et al. 2004., p. 8.

- ↑ Jarboe, War News 2016, p. 26.

- ↑ Sundaram, Chandar: Indianization, the Office Corps, and the Indian Army. The Forgotten Debate, 1817-1917, Washington, D. C. 2019.

- ↑ The Tribune, 25 July 1915; India Office Records IOR/L/R/5/196.

- ↑ Jarboe, War News 2018, p. 83.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 65.

- ↑ Government of India: India’s Contribution to the Great War, Calcutta 1923, p. 277.

- ↑ Jarboe, War News 2018, p. 147.

- ↑ Ibid, p. 146.

- ↑ See parliamentary speeches, Mr David Lloyd George, issued by Hansard, online: https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/people/mr-david-lloyd-george/1918 (retrieved: 23 April 2021).

- ↑ Jarboe, War News 2018, p. 198.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 27.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 9.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 9.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 84-85.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 209.

- ↑ Not unlike the letters Indian soldiers sent home from the frontlines. See Singh, Between Self and Sepoy 2014, p. 185.

- ↑ O’Dwyer, Michael: India as I Knew it, 1885-1925, London 1926, p. 175.

- ↑ Jarboe, War News 2018, p. 10.

- ↑ The Press Act, in: The Indian Review, volume 17, p. 391.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 392.

- ↑ Jarboe, War News 2018, p. 136.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ The End of the War, in: The Indian Review, volume 19, p. 745.

- ↑ India and Self-Determination, in: The Indian Review, volume 20, p. 41.

- ↑ Manela, Erez: The Wilsonian Moment. Self-Determination and the International Origins of Anticolonial Nationalism, Oxford 2009, p. 168.

- ↑ Hunter Commission, India Office Records IOR L/MIL/17/12/42, p. 59.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ See for example, The Amrita Bazar Patrika 13 March 1919, in: Gandhi, Mahatma: The Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi, volume 17, Ahmedabad 1965, p. 324.

- ↑ See Wagner, Kim A.: Amritsar 1919. An Empire of Fear and the Making of a Massacre, New Haven et al. 2019.

- ↑ Hunter Commission, India Office Records IOR L/MIL/17/12/42, p. 86.

- ↑ A Perilous Policy, in: The Indian Review, volume 21, p. 552.

Selected Bibliography

- Barrier, N. Gerald: Banned. Controversial literature and political control in British India, 1907-1947, Columbia 1974: University of Missouri Press.

- Barrier, N. Gerald / Wallace, Paul: The Punjab press, 1880-1905, East Lansing 1970: Michigan State University Press.

- Report of the Committee Appointed by the Government of India to Investigate the Disturbances in the Punjab, London 1920: H.M. Stationary Office, 1920.

- Das, Santanu: Sepoys, Sahubs, and Babus. India, the Great War and two colonial Journals, in: Hammond, Mary / Shafquat, Towheed (eds.): Publishing in the First World War, London 2007: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 61-77.

- Das, Santanu: India, empire, and First World War culture. Writings, images, and songs, Cambridge 2018: Cambridge University Press.

- Gerwarth, Robert / Manela, Erez (eds.): Empires at war, 1911-1923, Oxford 2014: Oxford University Press.

- Government of India: India's contribution to the Great War, Calcutta 1923: Superintendent Government Printing.

- Jarboe, Andrew Tait (ed.): War news in India. The Punjabi press during World War I, London 2016: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Jarboe, Andrew Tait / Fogarty, Richard (eds.): Empires in World War I. Shifting frontiers and imperial dynamics in a global conflict, London; New York 2014: I. B. Tauris.

- Joshi, Sanjay: Fractured modernity. Making of a middle class in colonial north India, New Delhi 2001: Oxford University Press.

- MacMunn, George Fletcher: The armies of India, Bristol 1911: A&C Books.

- Manela, Erez: The Wilsonian moment. Self-determination and the international origins of anticolonial nationalism, Oxford; New York 2007: Oxford University Press.

- Morton-Jack, George: Army of empire. The untold story of the Indian army in World War I, New York 2018: Basic Books.

- O'Dwyer, Michael: India as I knew it, 1885-1925, London 1925: Constable & Co..

- Roy, Kaushik: Indian Army and the First World War. 1914-18, Oxford 2018: Oxford University Press.

- Singh, Gajendra: The testimonies of Indian soldiers and the two world wars. Between self and Sepoy, London 2014: Bloomsbury.

- Sinha, Mrinalini: Colonial masculinity. The 'manly Englishman' and the 'effeminate Bengali' in the late nineteenth century, Manchester 2017: Manchester University Press.

- Streets-Salter, Heather: Martial races. The military, race and masculinity in British imperial culture, 1857-1914, Manchester 2004: Manchester University Press.

- Sundaram, Chandar: Indianization, the Office Corps, and the Indian Army. The forgotten debate, 1817-1917, Washington, D.C. 2019: Lexington Books.

- Wagner, Kim: Amritsar 1919. An empire of fear and the making of a massacre., London 2019: Yale University Press.