South East Europe and Wars preceding the Great War: 1908-1913↑

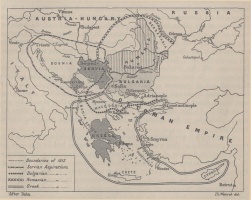

The beginning of the 20th century in South East Europe (the Balkans and Romania) was marked by a series of crises. A coup d’état in Serbia and the Ilinden Uprising in Macedonia and Thrace in 1903, the Young Turk Revolution, the Austro-Hungarian annexation of Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1908, and the subsequent Serbian and Montenegrin consternation. In addition, there were a series of Albanian uprisings against central Ottoman power in 1909, 1910, 1911 and 1912;[1] Bulgarian, Serbian, and Greek comitaji actions in Ottoman Macedonia in 1903‒1912; and, Austro-Hungarian economic sanctions against Serbia. The culmination of these crises was the Balkan Wars of 1912‒1913, which resulted in the expulsion of the Ottoman Empire from Europe and a major reshaping of the political map of this part of Europe. Greece, Serbia, Montenegro and Bulgaria enlarged their territories and, at the same time, the newly independent state of Albania emerged. However, while the historians’ interpretation of the First Balkan war is positive, the Second was best described as an “inter-allied war”, as it is commonly known in Bulgarian historiography. This war led to the creation of deep animosity between, on one side, Serbia and Greece whose main concern was blocking Bulgarian attempts to revise the Treaty of Bucharest which marked the end of Second Balkan War and on the other side Bulgaria which sought to get a rematch and finally incorporate Macedonia. After losing its Libyan and its European provinces, the Ottoman Empire under the Young Turks engaged in a series of complex military reforms under the guidance of a German military mission.[2] Romania, however, began slowly drifting away from its long-time Austro-Hungarian ally.[3] This article presents the position of each South East European nation, their war plans – if they existed – or, at the very least, their political situation when they were drawn into the Great War.

Military Planning in South East Europe: Hopes, Fears and Expectations↑

Serbia, Montenegro and Austria-Hungary↑

Serbia and Austria-Hungary had a history of tense relations prior to World War I. Immediately after the 1903 coup d’état and the change of the ruling dynasty, Serbia changed the orientation of its foreign policy, moving closer to the Russian Empire, while at the same time relying on France for financial assistance and armament procurement.[4] Montenegro, however, continued to maintain firm and close relations with Russia.

The Austro-Hungarian proclamation of its annexation of Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1908 caused serious consternation in Serbia and Montenegro. However, Serbia and Montenegro, lacking the support of Russia – which had been weakened by its defeat in the war with Japan – did not go to war. As a result of the annexation crisis, the Serbian General Staff produced a war plan in 1908, which was the foundation of the Serbian war plan in 1914.[5]

The basic assumption of the Serbian war plan was a defensive stand against Austria-Hungary until the political and strategic situation could no longer be upheld and then to react to the situation. Keeping in mind the defensive nature of the Serbian plan, no operational plan was produced that left room for additional intervention once the enemy had revealed its intentions. Although Serbia had a defensive agreement with Greece, Serbian military planners could only count on support from Montenegro. According to its analyses of Austro-Hungarian intentions, its railway network as well operational directions ‒ which led towards the Serbian interior ‒ the Serbian General Staff expected the main Austro-Hungarian force to advance from the north following the Velika Morava and Kolubara river while smaller additional forces would enter Serbia from Bosnia and Herzegovina. Serbia deployed its eleven infantry divisions, one cavalry division and forty third-line battalions accordingly. In case of new developments (which eventually came to pass), Serbian troops could advance west towards the river Drina as well as east and south east against a possible Bulgarian attack. It was foreseen that to the south west one Serbian army corps, together with some 20,000 Montenegrins, would advance towards Sarajevo, if the overall situation allowed such an action.[6] After the formal declaration of war, Serbian Chief of Staff, Field Marshal Radomir Putnik (1847-1917), created a Joint Operational Plan of the Serbian and Montenegrin Armed Forces, whose main goal was to attract and engage as many Austro-Hungarian forces as possible in order to weaken their actions against Russia.[7] The Montenegrin army was small – around 35,000 soldiers with some logistic and other non-combatant units – and it resembled a militia more than a modern army because it was organized along the clan structures of Montenegrin society. However, it was a highly motivated and battle-hardened army, and one particularly suited for mountain warfare. One Montenegrin weakness was a lack of trained staff officers. So immediately after the outbreak of war, Nikola I, King of Montenegro (1841-1921) asked for Serbian assistance in the form of staff officers who would plan and coordinate joint actions. As a result, Serbian General Božidar Janković (1849-1920) was appointed Chief of the Montenegrin Supreme Command. Initially, Montenegrin forces were divided into four detachments. There were 6,000 men near the Sanjak, 15,000 near Herzegovina, 8,000 near the Bay of Kotor and 6,000 near Albania. However, according to the Joint Operational Plan, which foresaw the engagement of two-thirds of the Montenegrin forces moving jointly with Serbian troops towards the Sanjak and further towards Bosnia, the regrouping of Montenegrin forces began immediately after the mobilization.[8]

The Austro-Hungarian Supreme Command under Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf (1852-1925) developed his own plan for a war against Serbia, after decades of precise intelligence collection regarding the Serbian state, its armed forces, people and geography, during the crisis of Austro-Hungarian annexation of Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1908. Although obsessed with his idée fixe of the annihilation of Serbia as main challenge for maintaining the integrity of Habsburg Empire, Conrad von Hötzendorf had to adapt this war plan to a political reality ‒ that in the future, Austria-Hungary's main opponent would not be Serbia, but Russia.[9] Hence, under the revised war plan, Austro-Hungarian forces amounted in total to 1,421,250 soldiers in combat arms and combat support units in forty-eight infantry, two militia (Landsturm), and eleven cavalry divisions, as well as twenty Landsturm brigades and numerous replacement (Marsch) brigades, with an additional 257 Landsturm battalions and thirty-two brigades for rear area duties.[10] These forces were divided into three groups. The sole purpose of the strongest one, the A-Staffel, was fighting against the Russians. The much smaller Minimalgruppe Balkan was to be used for operations against Serbia and Montenegro. Finally, the B-Staffel was to be deployed to one front or another depending on circumstances. This was the assumption of the R version of the plan. The B version of the plan was considered less likely and foresaw action solely against Serbia (and Montenegro), where the Minimalgruppe Balkan would be used with the B-Staffel without full mobilization of Austro-Hungarian armed forces. Contrary to Serbian assumptions, the Austro-Hungarian plan foresaw a main offensive that would come across rivers Drina and Sava in the West and North West sections, and not across the Danube from the North.[11] In addition, their plan was based on an assumption that Russian mobilization would be slow. Conrad von Hötzendorf believed that he would have enough time to defeat Serbia before Russian troops became fully operational. Unlike its plan for Serbia, the Austro-Hungarian command did not plan offensive actions against Montenegro. Instead, they built lines of smaller fortresses and blockhouses in Herzegovina and the Bay of Kotor against which Montenegrin army was practically powerless because it did not possess large caliber artillery (all Montenegrin artillery, some sixty pieces, was light and transported by pack animals).[12]

Eventually, the flexibility of the Serbian and Montenegrin deployment as well as the insufficient strength of Austro-Hungarian forces (450,000 against 300,000 Serbian and Montenegrin)[13] made it possible for Serbian troops to outmaneuver the Austro-Hungarian armies and defeat them in the 1914 campaign.

Bulgaria↑

After its defeat in Second Balkan War in 1913, Bulgaria was faced with territorial losses and isolation. The war was characterized as a national catastrophe and Bulgarian authorities decided to apply a pragmatic policy in order to set up a rematch and effect a return of the lost territories to Bulgarian sovereignty.[14] In the beginning, the Bulgarian decision to remain neutral was welcomed, both by the Entente and Central Powers as well by Bulgaria’s Balkan neighbors – Romania, the Ottoman Empire and Greece. However, in a short time Bulgarian neutrality became uncomfortable for the two military alliances, which both tried to attract Bulgaria to join their side. In Sofia, the territorial compensations offered by Germany were considered the most appropriate to Bulgarian national interests.[15] Offers made by Entente to Bulgaria considered ceding Serbian and Greek territories – Macedonia and areas around towns Kavala, Drama and Serres – to Bulgaria. In return, Serbia and Greece were offered territorial compensations elsewhere. Serbia declined while Greece insisted on stronger guarantees before it would give up recently won territories.[16] The situation became clear on 6 September 1915, when Bulgaria signed a treaty of alliance with Germany, followed by the signing of military conventions with the Chiefs of Staff of Germany and Austria-Hungary, German financial aid, and general mobilization on 21 September.[17] A few days earlier on 3 September, Bulgaria and the Ottoman Empire signed the “Agreement for the Correction of the Border”, under which Ottoman territories west of the Maritza and Tundza Rivers were handed over to Bulgaria.[18] In essence, this meant that Bulgaria had secured its rear for the forthcoming campaigns against Serbia and Romania the following year. Serbian Prime Minister Nikola Pašić (1845-1926), supported by his Greek counterpart Eleutherios Venizelos (1864-1936), insisted on a preemptive strike before Bulgaria could finish mobilizing and concentrating its armies. However, the Entente – primarily Great Britain – strongly objected.[19] Bulgaria was left undisturbed to mass and deploy its forces for the campaign against Serbia. In total, Bulgarians mobilized 15,908 officers and 600,772 Non-commissioned officers and privates. Like other South East European armies, the Bulgarian army suffered from shortages of modern weapons, ammunition, uniforms, signal equipment, modern means of transportation, etc.[20]

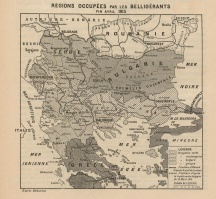

The basis of the Bulgarian plan was the B-G variant of the war plan for a simultaneous war against Serbia and Greece. It was aligned to the joint German-Austro-Hungarian-Bulgarian plan, called the Mackensen Plan, after the German general and commander of the joint forces for the campaign against Serbia, August von Mackensen (1849-1945).[21] The plan foresaw the deployment of one Bulgarian army (the 1st) in the “Mackensen” army group (with the 3rd Austro-Hungarian and the 11th German armies) under German command which would operate toward the Timok and Nišava rivers in the direction of the Morava valley. Two other armies operated under the Bulgarian command, the 2nd moving toward central Macedonia from Ćustendil to Kumanovo and the 3rd which was charged with securing the Bulgarian-Romanian border. Two independent divisions had the same task on the Bulgarian-Greek border.[22] As agreed, the Bulgarian offensive against Serbia started on 14 October, one week after the German-Austro-Hungarian attack.[23] The Serbian army, outnumbered, outgunned, and without Allied support, was forced to a general withdrawal on all fronts.

Greece↑

On the eve of World War I, the position of Greece was characterized by the personal relations and political affiliations of two leading figures in Greek political life – Prime Minister Eleutherios Venizelos and Constantine I, King of Greece (1868-1923). Closely connected with Germany – by marriage to Sophia of Prussia (1870-1932), the sister of Wilhelm II, German Emperor (1859-1941), and a high rank in German army – the King argued for neutrality. On the other hand, Venizelos argued for a Greek entry to the war on the side of the Entente, seeing in their victory an opportunity for Greek territorial expansion.[24] Above all, after victories in the Balkan wars and the Greek expansion to Macedonia, Epirus, Crete and the Aegean islands, the vision of the “Great Idea”, i.e. a Hellenic expansion to the old Byzantine geographic and cultural framework, seemed possible.[25] When at the end of 1914 and the beginning of 1915 a diplomatic “race” for new allies in the Balkans began, the Greek internal dilemma became even more complex. On top of everything, Greece and Serbia had a military agreement which soon proved to be moot, since Greece was reluctant to help Serbia militarily against Austro-Hungary.[26] Thus, Greece found itself trapped among the political affiliations of its prominent political leaders, strong Allied demands for the ceding of some territories to Bulgaria, weak Allied promises of new gains in Asia Minor, military pressure from the Central Powers, allied obligations towards Serbia, and its own revived idea of national expansion.[27]

A series of blows occurred in 1915 that eventually led to serious national split termed the National Schism, a situation that resembled civil war.[28] Greek willingness to help the Allies at Gallipoli was blocked by a Russian refusal to accept any flag but their own over Constantinople.[29] The period between Venizelos’ first resignation in March and his second in October was marked by Bulgaria joining the Central Powers, the partial mobilization of the Greek army, the start of the Allied landing in Thessaloniki and the final refusal of the King Constantine to implement the Greek-Serbian treaty.[30] The creation of the Thessaloniki front and the arrival of the Serbian army after its withdrawal across Albania in 1916 contributed new tensions between authorities in Athens ‒ who were on paper neutral ‒ and the Allies. When pro-Venizelos officers in August 1916 staged a coup d'état in Thessaloniki, the National Schism became full-fledged. In December 1916 the Allies tried unsuccessfully to force royalists in Athens to remain neutral. That led to Allied recognition of the Venizelos government in Thessaloniki and eventually a new intervention in 1917. King Constantine was forced to abdicate and Venizelos returned to power in triumph.[31] This finally untied Venizelos’ hands and he was able to execute his plans for expansion. The first act of his government was official entry of Greece into World War I on side of the Entente.[32] The Greek contribution to the breakthrough on the Thessaloniki front in September 1918 and the intervention against the Bolsheviks was the prelude to a Greek landing in Smyrna in May 1919 and a catastrophic campaign in Asia Minor.[33] It was beginning of the end of a 2,500-year long Greek presence in Asia Minor.

Romania↑

When the war started in 1914, Romania was still bound to the Central Powers by a secret defensive military pact which became void because Austro-Hungary declared war on Serbia.[34] However, due to the intensive political activity of Romanian Prime Minister Ion Brătianu (1864-1927), Romania shifted its foreign policy towards the Entente. Strong pro-French sentiments in Romania as well the fact that more than 3 million ethnic Romanians lived in Austro-Hungary, specifically Transylvania, facilitated this change.[35]

Until 1914 Romanian military planning was focused on Russia as the principal enemy. In the case of conflict between the Central Powers and Russia, the Romanian army would advance towards the Ukraine. However, Brătianu modified this, issuing an order to the military planners to prepare a plan for war against Austro-Hungary. This plan had several variants following changes that occurred from 1914 to 1916 (such as the Bulgarian alliance with Central Powers). Its main goal ‒ the conquest of Austro-Hungarian territories populated by ethnic Romanians ‒ remained the same. The final version of the plan from August 1916, Hypothesis Z, was predicated on a war on two fronts where the majority of the Romanian forces (65 percent) would be deployed against Hungary for offensive action while the smaller part (25 percent) was given a defensive role on the southern front along the Danube and in Dobruja against Bulgaria. The rest (10 percent) represented a general reserve stationed in the vicinity of Bucharest.[36] It numbered 800,000 men in total; the majority of them were reservists. Compared to its enemies, the Romanian army suffered from serious shortages in communications equipment and modern weapons, such as machine guns and rapid firing artillery. At the same time, the size of both the officer and NCO corps was inadequate and lacked military training. Romanian tactics were outdated and their military experts were unaware of recent changes in warfare.[37]

The Romanian war plan had several weak points which eventually proved crucial to its failure. It did not calculate the possibility of enemy reinforcements on the north and south fronts. Moreover, it relied too extensively on Allied actions on the western, eastern and Macedonian fronts, and did not take into account the possibility of an Ottoman contingent on its south front. Although it assumed cooperation with Russian forces, the plan did not address the details of joint operations.[38] The Romanian army was given an assignment for whose execution it lacked training, firepower, equipment, experience, leadership and capable staff officers – everything its adversaries had in abundance.

The Ottoman Empire and the Balkans↑

When hostilities started in World War I, the Ottoman Empire found itself under strong pressure from Germany to enter the war on the side of the Central Powers. From the German point of view, an Ottoman declaration of war on Russia and Great Britain, followed by demonstrations in the vicinity of Odessa and the Suez Canal, would improve the position of German and Austro-Hungarian forces which were bogged down on the Marne, in Galicia and in the Balkans. At the same time, Germany was involved in an attempt to create an alliance of Balkan states, Romania, Greece and Bulgaria, that was closely tied to the Central Powers. Both attempts, however, proved futile.[39] To apply pressure, Germany refused the continuation of military aid to the Ottomans.[40] After a series of meetings and negotiations in September and October 1915, Germany provided the Ottomans with financial assistance and they in turn agreed to enter the War on the side of Central Powers.[41]

However, the Ottoman armed forces had suffered a severe blow in the newly ended Balkan Wars and a single year was not sufficient time to reorganize its shattered armies. Entire units had been dissolved, and both training and procurement were at a standstill. Although the presence of the German military mission proved essential to a great extent for the regeneration of the Ottoman regular army, it could not compensate previous losses.[42]

Ottoman Chief of Staff Ismail Enver Pasha (1881-1922) submitted an Ottoman plan for German approval. Basically, this war plan consisted of six points and variants:

- A naval operation against the Russian fleet in the Black Sea followed by a proclamation of jihad and a declaration of war against the enemies of Germany, Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman Empire.

- Defensive operations against Russian forces in Transcaucasia.

- Demonstration against British forces in Egypt.

- In the case of a Bulgarian entry into the alliance, Ottoman forces would participate in an offensive against Serbia.

- In the case of a Romanian entry into the alliance, Ottoman forces would participate in an offensive against Russia.

- A naval operation against Odessa with strength of three to four corps.

Both the content of the proposed war plan and the request for German approval reflected Ottoman commitment to the German war, which was intended eventually to win the Porte equal participation in a post-war settlement.[43] What the actual Ottoman war aims were is perhaps best described by six demands made by the Ottoman Foreign Minister Said Halim Pasha (1864-1921) to the German diplomatic representative Hans Freiherr von Wangenheim (1859-1915). They were: 1) a German promise to help abolition of the capitulations; 2) German help in reaching settlements with Romania and Bulgaria; 3) that Germany would not conclude peace unless all occupied Ottoman territories were evacuated; 4) in case of a Greek entry into the war on side of the Entente and a subsequent Greek defeat, that Germany would help regain Aegean islands for the Ottomans; 5) German assistance in obtaining a small modification of its eastern border; 6) that Germany would ensure that the Ottoman Empire receive suitable war indemnity.[44] Both the Enver Pasha’s plan as well Sait Halim’s demands made it obvious that the Balkans were a low priority for the Ottoman war planners.

Following the previously mentioned war plan, Ottoman Empire entered the war on the side of the Central Powers on 10 November 1914 with a declaration of war on Russia and its allies, France and Great Britain. In the following days, they also declared war on Belgium, Serbia and Montenegro.[45]

Conclusion↑

From Serbia and Montenegro in 1914, to Greece in 1917, one country after the other in South East Europe entered the largest war in previous history. The questions were on whose side did they fight and did they achieve what they had hoped for? Although almost each country had its own war plans which had been created previously, the fact that they allied themselves with Great Powers who were confronting each other meant primarily that they had to commit their own war effort to a joint cause. Their territories became subject to various negotiations and re-combinations, and their armies had to coordinate their actions with allied armies. Being poor and recently out of the Balkan Wars, they had to rely on the support of their allies, which ultimately only strengthened their already existing sense of dependency.

Dmitar Tasić, Institute for Strategic Research, Belgrade

Section Editors: Richard C. Hall; Tamara Scheer; Milan Ristović

Notes

- ↑ Bartl, Peter: Albanians, from Medieval to Modern Times, Belgrade 2001, pp. 124-138.

- ↑ Further readings: Aksakal, Mustafa: The Ottoman Road to War in 1914. The Ottoman Empire and the First World War, Cambridge 2008.

- ↑ Further readings: Torrey, Glenn E.: The Romanian Battlefront in World War I, Lawrence 2012.

- ↑ History of Serbian nation VI-2, From Berlin congress until unification 1878 – 1918, Belgrade 1994, p. 25.

- ↑ Opačić, Petar: Austro-Hungarian war plan against Serbia and Serbian war plan for the defense of country against Austro-Hungarian aggression, in: Čubrilović, Vasa (ed.): Great Powers and Serbia on the eve of First World War, Conference proceedings 13-15 September 1974, Belgrade 1976, p. 513.

- ↑ Opačić, Austro-Hungarian war plan against Serbia 1976, pp. 513-514 and 516.

- ↑ Opačić, Austro-Hungarian war plan against Serbia 1976, p. 517.

- ↑ Zelenika, Milan: The First World War 1914, Belgrade 1962, pp. 148-150.

- ↑ Opačić, Austro-Hungarian war plan against Serbia 1976, p. 500. See also: Tunstall, Graydon A. Jr.: Planning for War against Russia and Serbia. Austro-Hungarian and German Military Strategies 1871 – 1914, New York 1993.

- ↑ Schindler, John R.: Disaster on the Drina: The Austro-Hungarian army in Serbia, 1914, in: War in History 9/2 (2002) pp. 159–195.

- ↑ Ortner, Mario Christian: War against Serbia 1914 and 1915 (Austrian perspective) in Vojnoistorijski glasnik 1(2010), pp. 111-132

- ↑ Zelenika, First World War 1962, p. 92.

- ↑ Ortner, War against Serbia 2010, pp. 115 and 126. Among 450,000 Austro-Hungarian troops engaged in Balkan campaign in 1914, a considerable number belonged to logistic units as well as to fort garrisons and other rear-area duties, making the overall ratio even more unfavorable for Austro-Hungarians.

- ↑ Stanchev, Stancho: Bulgarian army in First World War, Sofia 2006.

- ↑ Stančev, Stančo: Participation of Bulgaria in First World War in the Balkans, in: The First World War on the Balkans, Conference proceedings Sofia 10-11 October 2005, Sofia 2006, p. 11.

- ↑ Klog, Richard: History of modern Greece, Belgrade 2000, p. 88 and History of Serbian nation VI -2, From Berlin congress until unification 1878 – 1918, p. 93.

- ↑ Stančev, Participation of Bulgaria in First World War 2006, pp. 11-12.

- ↑ Fidan, Nurjan: Joint Turkish-Bulgarian military operations during First World War, in: Tsvetkovm, Chavdar: Bulgarian-Turkish Military-political Relations in the First Half of 20th Century, Sofia 2005, p. 56.

- ↑ Le Moal, Frédéric: La Serbie. Dy martyre à la victorie 1914 – 1918, Paris 2008, pp. 84-85.

- ↑ Vasilev, Vasil: Bulgarian army 1877–1919, Sofia 1988, p. 285.

- ↑ Vasilev, Bulgarian army 1988, p. 73.

- ↑ Vasilev, Bulgarian army 1988, p. 73-74.

- ↑ Vasilev, Bulgarian army 1988, p. 289.

- ↑ Klog, History of modern Greece 2000, p. 87.

- ↑ Klog, History of modern Greece 2000, p. 87.

- ↑ Katsikostas, Dimitrios: The outbreak of the Hellenic split in the context of the WWI, in: First World War and the Balkans – 90 years later, Collection of papers, Belgrade 2010, pp. 81-94.

- ↑ Klog, History of modern Greece 2000, pp. 88-89.

- ↑ Klog, History of modern Greece 2000, p. 87.

- ↑ Katsikostas, The outbreak of the Hellenic split 2010, p. 90.

- ↑ Katsikostas, The outbreak of the Hellenic split 2010, pp. 90-95.

- ↑ Klog, History of modern Greece 2000, pp. 92-94.

- ↑ Hellenic Army General Staff: A History of the Hellenic Army 1821-1997, Athens 1999, p. 134.

- ↑ Klog, History of modern Greece 2000, p. 94.

- ↑ Dumitru, Laurenţiu Cristian: July – August 1914. Romania Denies to Attack Serbia, in: First World War and the Balkans – 90 years later, Collection of papers, Belgrade 2010, pp. 9-18.

- ↑ Torrey, The Romanian Battlefront 2012, p. 3.

- ↑ Torrey, The Romanian Battlefront 2012, pp. 21-23.

- ↑ Torrey, The Romanian Battlefront 2012, pp. 14-21.

- ↑ Torrey, The Romanian Battlefront 2012, p. 24.

- ↑ Aksakal, The Ottoman Road to War 2008, pp. 141-144.

- ↑ Aksakal, The Ottoman Road to War 2008, p. 147.

- ↑ Aksakal, The Ottoman Road to War 2008, p. 171.

- ↑ Erickson, Edward J: Ordered to die. A History of the Ottoman Army in the First World War, Westport 2001, pp. 10-11.

- ↑ Aksakal, The Ottoman Road to War 2008, p. 173.

- ↑ Erickson, Ordered to die 2001, p. 27.

- ↑ Aksakal, The Ottoman Road to War 2008, p. 183.

Selected Bibliography

- Aksakal, Mustafa: The Ottoman road to war in 1914. The Ottoman Empire and the First World War, Cambridge 2008: Cambridge University Press.

- Bartl, Peter: Albanien. Vom Mittelalter bis zur Gegenwart, Regensburg 1995: Pustet.

- Clogg, Richard / Ristović, Milan: Istorija Grčke novog doba (History of modern Greece), Belgrade 2000: Clio.

- Čubrilović, Vasa (ed.): Velike sile i Srbija pred prvi svetski rat. Zbornik radova prikazanih na međunarodnom naučnom skupu Srpske akademije nauka i umetnosti, održanom od 13-15, septembra 1974. Godine u Beogradu (Great forces and Serbia on the eve of the First World War. Conference proceedings 13-15 September 1974), Belgrade 1976: Srpska akademija nauka i umetnosti.

- Erickson, Edward J.: Ordered to die. A history of the Ottoman army in the First World War, Westport; London 2001: Greenwood Press.

- Gavrilović, S.: History of the Serbian nation. From the Berlin congress until unification 1878-1918, Belgrade 1994.

- Hellenic Army General Staff (ed.): A history of the Hellenic Army 1821-1997, Athens 1999: Hellenic Army General Staff Army History Directorate.

- Institut za strategijska istraživanja: Prvi svetski rat i Balkan – 90 godina kasnije, Tematski zbornik radova (First World War and the Balkans – 90 years after. Collections of papers), Belgrade 2010: Institut za strategijska istraživanja.

- Mario, Ortner Kristijan: Rat protiv Srbije 1914. i 1915. Pogled iz Austrije (The war against Serbia 1914-1915. The Austrian perspective), in: Vojno-istorijski glasnik/1 , 2010, pp. 111-132.

- Moal, Frédéric Le: La Serbie. Du martyre à la victoire, 1914-1918, Saint-Cloud 2008: 14-18 éd..

- Schindler, John: Disaster on the Drina. The Austro-Hungarian army in Serbia, 1914, in: War in History 9/2, 2002, pp. 159-195.

- Stanchev, Stancho: Bŭlgarskata armii︠a︡ v Pŭrvata svetovna voĭna (Bulgarian army in First World War), volume 1, Sofia 2005: Военно изд-во.

- Torrey, Glenn E.: The Romanian battlefront in World War I, Lawrence 2011: University Press of Kansas.

- Tsvetkovm, Chavdar (ed.): Bulgarian-Turkish Military-political Relations in the First Half of 20th Century (collection of papers), Sofia 2005.

- Vasilev, Vasil A.: Bulgarskata Armija 1877-1919 (Bulgarian Army 1877-1919), Sofia 1988.

- Zelenika, Milan: Prvi svetski rat 1914 (First World War 1914), Belgrade 1962.