The Victim↑

Robert Paul Prager was born on 28 February 1888 in Dresden, Germany. He emigrated from Germany to Baltimore, Maryland, United States of America in April 1905. Prager’s peripatetic American lifestyle, in which he often worked as a baker, took him west to Lake County in the northwest corner of Indiana, to various municipalities in Nebraska, and, by 1916 to St. Louis, Missouri. A year later when the United States entered World War I, Prager’s attempt at naval enlistment proved unsuccessful, probably as a result of physical disqualification. Prager also submitted paperwork seeking to become a naturalized U.S. citizen, a process that was underway at the time of his death. Later in 1917, Prager relocated to Collinsville, approximately twelve miles east of St. Louis in Madison County, Illinois. He subsequently worked as a nighttime laborer at a local coal mine, where he sought to join a local mining union in hopes of securing a miner’s higher pay. For unknown reasons, Prager ran afoul of union bureaucrats controlling labor accessions in the mines who in early 1918 accused him, without evidence, of espionage and sabotage activities as a German agent. Because of his alleged "disloyalty" to the United States and lack of mining experience, they denied him union membership, meaning that he would not be employed as a miner there nor accrue the associated pay raise.

The Context↑

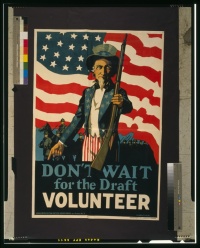

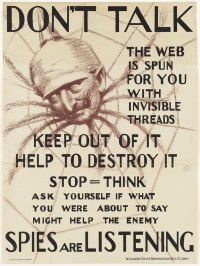

Bituminous coal deposits underlying Madison County made it a hub of mining and smelting activity, with coal from local mines fueling nearby large-scale smelting activities that recovered zinc, lead, and other metals, resources that were much in demand upon U.S. entry into World War I. Rich Illinois coal seams also powered the engines of locomotives and vessels that transported military personnel and their weapons, foodstuffs, and countless other commodities across the continent and ultimately to Europe in support of the victory over Germany. A torrid, war-energized economy drove surging inflation, difficult working and living conditions such as scarce, often inadequate housing, and myriad other challenges that roiled workplaces in Madison County and elsewhere across the country. In early July 1917, just a few months after the U.S. entered the war, dozens or perhaps even hundreds --the exact death toll may never be known-- perished when labor conflict engulfed East St. Louis, in the county immediately south of Madison County. This unrest occurred in tandem with racial strife accompanying the so-called "Great Migration" of African-Americans relocating north to contribute to the wartime mobilization effort. Upheaval arrived in Madison County itself later that year with labor union campaigns to organize local industry, some of which had never before had a unionized workforce and opposed any change to that heritage. Suspicions ran high that immigrants, whether African-Americans newly-arrived from the American South or those coming from outside the country, possessed dubious loyalty to the organized labor movement and, more generally, to the U.S. cause in its hostilities against Germany. A newcomer to the workplace might attempt to destroy local mines through sabotage, or might attempt to destroy unions by crossing striking workers’ picket lines. An outsider like Prager, lacking as he was in any bona fides that validated his loyalty to either cause, was therefore hardly welcome amidst the near paranoia that predominated in early 1918.

The Murder↑

Prager’s conflict with union officials in his attempt to gain union membership and employment as a miner resulted in a mob, many of whom were intoxicated, abducting him from his residence. These captors then forced Prager to march along Collinsville’s streets while, over the course of several hours, they repeatedly assaulted him with punches and kicks, forced him to walk barefoot over tacks, and subjected him to other forms of torture. Collinsville police officers were on the scene but failed to intervene. At Bluff Hill just west of Collinsville, in the early morning darkness of 5 April 1918, several of those in the mob placed a noose on a hackberry tree and proceeded to kill Prager by hanging. His last request, after he had written a letter to his family informing them of his imminent death, was burial wrapped in an American flag. His body hung from the hackberry tree on Bluff Hill until city officials recovered it later that day. Searches of Prager’s residence after his murder yielded no evidence that Prager had known of, planned, or participated in espionage, sabotage, or other subversive activity of any kind.

The Trial↑

On 12 April 1918, two days after Prager was laid to rest at a St. Louis cemetery, twelve men were indicted for his murder. Only eleven of the twelve indicted individuals could be located for arraignment, which took place on 2 May 1918 and resulted in all eleven, who ranged in age from seventeen to forty-four, pleading not guilty. Four Collinsville police officers who had been on duty at the time of Prager’s murder were also indicted on different charges relating to a failure to discharge their official duties. All eleven defendants were tried together at the courtroom of Third Judicial Circuit Judge Louis Bernreuter (1863-1944) in Madison County seat Edwardsville, with the trial opening on 13 May 1918. The prosecution subsequently called twenty-six witnesses in an attempt to link the defendants with Prager’s homicide. On 1 June 1918, the jury acquitted all eleven men. Charges were later dropped against the four Collinsville police officers, and no one else was ever indicted, let alone tried, in relation to Prager’s death.

The Legacy↑

Robert Prager’s death resulting from mob violence both reflected, and resulted from, trends in the United States during the early twentieth century. Labor relations had deteriorated into an abominable state, with unions struggling against determined corporate resistance to gain recognition for their organizations in mining, smelting, and many other economic sectors. American participation in World War I helped foment misguided fixation on "loyalty" that occasionally mutated into extremism. In Prager’s case, officials in President Woodrow Wilson’s (1856-1924) cabinet offered little constructive opposition to the extremism that resulted in his death. In yet another example of obsession with ‘loyalty’, cabinet officials blamed the U.S. Congress for what they perceived to be inadequacies in federal sedition laws, rather than holding responsible those who actually killed Prager. The German government took advantage of this apparent official indifference to justice in highlighting, via complaint through Swiss intermediaries shortly after the Prager defendants’ acquittal, a glaring contrast between the ‘interests of humanity’ ostensibly motivating U.S. war efforts, and Prager’s inhuman mistreatment. Terrorism masquerading as patriotism arose from these dangerous developments, targeting Prager with its lethal hatred, whose ethnicity and socioeconomic status left him vulnerable. Bystanders, and even police officials, lacked the wherewithal to defend American institutions such as due process and presumption of innocence by stopping mobs from their deadly work. The manifest injustice that Prager suffered prefigured by one year a paroxysm of unrest that burned through American cities during 1919’s horrific Red Summer. Both episodes, Prager’s lawless death and similar depredations on a larger scale during the Red Summer a year later, betrayed Woodrow Wilson’s stated ideals for taking the United States into World War I, marking a very difficult era in the country’s history.

Derek Varble, Independent Scholar

Section Editor: Mark E. Grotelueschen

Selected Bibliography

- Kennedy, David M.: Over here. The First World War and American society, New York 1980: Oxford University Press.

- Secret inquiry held in Prager lynching, in: The New York Times, 9 April 1918, p. 5

- Stehman, Peter: Patriotic murder. A World War I hate crime for Uncle Sam, Lincoln 2018: University of Nebraska Press.

- The Prager case, in: The New York Times, 3 June 1918, p. 10

- Weinberg, Carl R.: Labor, loyalty, and rebellion. Southwestern Illinois coal miners and World War I, Carbondale 2005: Southern Illinois University Press.