Introduction↑

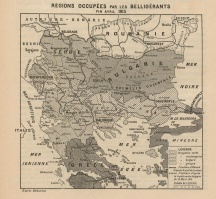

The Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes was created in 1918 when the Croatian and Slovene territories of the Austro-Hungarian Empire merged with the kingdoms of Serbia and Montenegro.[1] The new country needed to forge a state while accommodating various national identities from both victorious and vanquished parties of the Great War, as well as integrating the peoples of the new territories of Kosovo and Macedonia conquered from the Ottoman Empire and Bulgaria in the Balkan Wars of 1912 and 1913. Simultaneously, armed groups roamed the countryside; some were hostile to the new state, while others were comprised of men who remained mobilised and sought relevance in the new post-war environment. Divided by pre-war loyalties, ethnic obligations, and wartime experiences, Yugoslav war veterans of both the Balkan Wars and the Great War played integral roles in fashioning the new state in their own image, even if those roles differed greatly and often created conflict. Some of the most significant ways in which veterans attempted to contribute to the making or breaking of Yugoslavia were through paramilitary groups and illegal political organisations, as well as through legitimate means; quite often it was through some combination of parts or all of these methods. This article focuses on a number of groups, and some of the more important individuals who populated them, to provide an account of veterans’ experiences in the new Yugoslavia. It features the more important members of Yugoslav society because of their influence on contemporary and later events, as well as because of the availability of their memoirs, biographies, and other pertinent primary documents.

Politics by Other Means: Račić and Radić↑

Elected to parliament (Skupština) in 1927 as a member of the People’s Peasant Party, Puniša Račić (1886-1944) was also the leader of the veterans’ organisation the Association of Serbian Chetniks – Petar Mrkonjić. Involved in pacifying newly incorporated regions, which in practice meant targeting ethnic Albanians in the Montenegro-Albania-Kosovo border area, Račić entered parliament favouring a “Great Serbian” program instead of the Yugoslavism of the interwar regime. As head of a paramilitary organisation and a politician, Račić effectively turned the former into a military wing of the Radical Party. As John Paul Newman notes, for Račić “politics was a mere continuation of war by other means.”[2] Applying violence during elections, the Chetnik organisation helped to give Yugoslav politics a martial character and reflected the hatred for parliamentary democracy that many veterans harboured. Under Račić, the Chetnik organisation increased its violent character, marginalised non-Serbs, and undermined the new state.

Račić was at the centre of perhaps the most significant event of Yugoslavia’s interwar period: the assassination of the Croatian People’s Peasant Party member, Stjepan Radić (1871-1928), in June 1928. Popular amongst Austria-Hungary’s ethnic Croatians, Radić represented a bulwark against Serbian hegemony in Yugoslavia. Radić remained outside of the Skupština for much of his career, often boycotting elections because of his hostility to the perceived Serbianising actions of the regime. He spent much of the Great War in Austro-Hungarian prisons for his outspokenness, which would also land him in trouble with the new Yugoslav regime of the interwar period. The shocking nature of his assassination had much to do with the fact that it took place during a parliamentary session in the course of which a heated debate turned violent. Stoked by weeks of increasing tensions in parliament and in the newspapers, Račić drew a gun and shot Radić. Two members of parliament were killed while two others were wounded. Radić was mortally wounded and died several weeks later. Radić’s death shaped interwar Yugoslavia’s socio-political landscape throughout the interwar period, hastening the radicalisation of Yugoslav politics, with war and politics often going hand in hand.

State and Nation Building in the South↑

The most important Chetnik organisation operating in interwar Yugoslavia was the Committee Against Bulgarian Bandits (CABB) founded in 1922. Though the Great War had ended, some Yugoslav veterans continued their campaigns against ethnic minorities and to win over the populations of acquired territories. Ensuring the war would continue, Račić founded the CABB with the aim to counter the Bulgarian nationalising project and to direct the populations towards Serbianisation to better lay claim to the territory. These “committee men” operated mostly in Macedonia, or “Southern Serbia” as the territory was called at the time, but also conducted operations in “Old Serbia,” or the Kosovo-Metohija region. Their opponent, the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organisation (IMRO), was most responsible for swaying the Macedonian population towards Bulgaria and away from Yugoslavia. To counter these measures, the CABB attempted to “cleanse” the territory of people claiming to be ethnic Bulgarians through murder, assimilation, or forced expulsion. These practices trace back to at least the Balkan Wars of 1912-1913 and followed the same pattern as in Macedonia: a voluntary or guerrilla unit would move into a village, attempt to convert the population, and deal swiftly with any resistance. The campaign of genocide was politicised by the royal Yugoslav government at various points, which co-opted the movement for its own political expediency, seeing the actions as beneficial to the regime’s unitary Yugoslav ideology. That many members of the committee and other organisations like it were also members of the national parliament helped to ensure the organisation’s legitimacy. When the practices were seen as dysfunctional or counterproductive, the government distanced itself from the units.

In addition to using semi-legal organisations, the regime founded schools to teach people Serbian. In 1920, the government unified all Orthodox churches under the Serbian Orthodox Church, thereby eliminating and subverting any claim to a separate Macedonian or Bulgarian identity. Bulgarian clergy were removed or forced to convert, while any Bulgarian language books and signs were taken away. Non-Serb schools and societies were disbanded. Peasants were Serbianised at gunpoint: they adopted the “-ić” suffix for their last names instead of the “-ski” or “-ov” common to ethnic Bulgarians and Macedonians; any resisters were killed, tortured, and/or imprisoned. The people of Macedonia rejected the Yugoslav authorities in the 1921 elections, in which the Communist Party swept the region prior to being made illegal.[3]

Kosta Milovanović-Pećanac (1879-1944) was another notorious figure in Macedonia. With a reputation from the Balkan Wars, Pećanac earned medals for bravery in the Serbian campaign of 1915 and the Serbian army’s subsequent retreat to Corfu. Pećanac’s reputation gained considerably for his role in the 1917 Toplica uprising which he harnessed into legendary status in the post-war period. Bulgarian occupation practices during the Great War included arbitrary punishments against Serbian civilians, the closing of Serbian-language schools, the destruction of Serbian cultural sites, and internment. Led by Pećanac, armed Serbs rose up against the Bulgarians but were soon destroyed.[4] Hoping to enact revenge for the events of 1917 where his units were unreservedly crushed, Pećanac’s units were responsible for countless acts of violence against non-Serbian ethnic groups in the interwar period. As a leading figure in the CABB, he astutely positioned himself to gain the leadership of the Chetnik Association in 1932.[5] Other leaders of the latter group included Račić, as mentioned, and Ilija Trifunović-Birčanin (1877-1943), and its prominent members included Dobroslav Jevdjević (1895-1962). Pećanac was present in the parliament on the day of Radić’s assassination. He represents not only the martial identity of Yugoslav politics but also the impact that the assassination undoubtedly had on several prominent members.

Under Pećanac’s leadership, the Chetnik Association took in new members who were too young to have any experience of the Great War. This not only expanded the organisation’s membership, keeping it relevant, but also ensured that Yugoslav society would remain at least partially mobilised. With the injection of youth, the organisation increased its reach and maintained its violence. Often mobilising in the runup to elections, the Chetnik Association followed the trend of anti-parliamentarianism prevalent in interwar Europe. Though the organisation could not be branded as fascistic, its extreme Serbian nationalism solidified its position on the extreme right of the spectrum.

Another right-wing Serbian nationalist organisation, which also had ties with the various Chetnik organisations, was the Serbian Cultural Club and its prominent figures Slobodan Jovanović (1869-1958), Isidora Sekulić (1877-1958), Dragiša Vasić (1885-1945), and Stevan Moljević (1888-1959). Further to the right of this organisation was Zbor, founded in 1934, whose leader Dimitrije Ljotić (1891-1945) previously fought on the Italo-Yugoslav front, was a member of the Radical Party from 1920-1926, and was an intellectual follower of Charles Maurras (1868-1952). Though Zbor and other groups varied on the right side of the political spectrum, they fall into the “para-fascist” category.[6] Ljotić and Zbor were not highly relevant, since its election results, martial character, and social presence were virtually inconsequential through the interwar period.

Only during the Second World War did many of these figures become at least somewhat relevant. For instance, the Yugoslav Army of the Fatherland, popularly known as the Chetniks, was led by Dragoljub “Draža” Mihailović (1893-1946), a decorated veteran of the Great War who retreated during the “Serbian Golgotha” in 1915. His interwar importance, however, was marginal and is therefore not recounted here. Regardless, his experiences in those conflicts and the radicalisation of the interwar Yugoslav climate undoubtedly contributed to his worldview and his actions during the Second World War. At least nominally aligned with Mihailović was Pećanac, along with Jevdjević and Birčanin. Moljević and Vasić would become Mihailović’s political and ideological founts while Jovanović served in the royal Yugoslav government-in-exile in the early years of the Second World War. Studying the intellectual shift of these men from the interwar period to 1941 and beyond would be an important contribution to better understanding how the interwar period radicalised these individuals to later formulate nationalistic programs. Though the Great War had ended, its shadow cast a long pall over Yugoslav society, culture, and politics. Much of the antagonism emanating from ethnic Albanians, Bulgarians, Croatians, Macedonians, and others towards ethnic Serbs, and especially towards the Serbian and Yugoslav governments, and vice versa, stems from the interwar period.

Underground Organisations↑

Ustaša↑

Ante Pavelić’s (1889-1959) Great War experience was political rather than martial. As a lawyer, he remained active in Austro-Hungarian politics and rejected the unification of ethnic Croatians with Serbs in 1918. Much of his and his party’s hostility was related to the existence of the Serbian king as head of state. As a witness to Radić’s assassination in 1928, Pavelić founded the Ustaša organisation. Taking its ideological program from Josip Frank’s (1844-1911) concept of “Croatian state right,” effectively a historical argument for the right of Croatia to maintain a state, Pavelić found powerful allies abroad, in particular Benito Mussolini (1883-1945). The relationship between Pavelić and Mussolini probably first manifested in the former’s defence of twenty Macedonian students accused of being members of the IMRO. Seeing the IMRO as an opportunity to weaken Yugoslavia’s territorial integrity, Mussolini gathered like-minded individuals such as Pavelić. Influenced by Karl Lueger’s (1844-1910) Christian Social movement and Italy’s fascism, the Ustaša took up armed militancy.[7] After the Yugoslav government banned the organisation in 1929, along with making all political parties illegal and the advent of a royal dictatorship, the Ustaša found refuge in Italy and received support from Hungary. Undoubtedly, the Ustaša’s hopes for Croatian independence meant that both Italy and Hungary had found a potentially vital revisionist ally. That the Ustaša territorial revision also included Dalmatia was a sticking point that could apparently be put off for the foreseeable future.

By the mid-1930s, support from Italy and Hungary seemed to bear fruit. With Hungary’s funds, Italy’s arms, and a territorial base on the western Adriatic coast for training, the Ustaša became more militant throughout King Aleksandar’s (1888-1934) dictatorship (1929-1934). The culmination of these forces led to the assassination of the king in 1934 while on a state visit to Marseille. Funded and trained by the Ustaša, a Macedonian revolutionary from the IMRO carried out the assassination. Rather than leading to widespread revolt against the Yugoslav state as intended, Yugoslavs of all nations took to the streets to mourn their king. Other than eliminating a powerful leader, the Ustaša failed to do anything else of material importance throughout its interwar existence. Though the Ustaša remained relatively quiet after 1934, they resurfaced in 1941 when the Italians and Germans installed Pavelić as Poglavnik (Führer) of the Independent State of Croatia. Like Mihailović, Pavelić’s importance came after the interwar period. However, studying those around Pavelić and their roles in interwar Yugoslavia (or Italy) would also be an important intervention for the period.

Communists↑

The Communist Party of Yugoslavs (CPY) came into being as a result of repatriated prisoners of war who had some experience of the Russian October Revolution of 1917. Josip Broz Tito (1892-1980) was one of these returnees. Though he was not a significant member of the CPY until the 1930s, he requires mention because of what he was able to accomplish in the 1930s and his subsequent involvement in the Second World War and the simultaneous Yugoslav Civil War (1941-1945), as well as his role as president of communist Yugoslavia from 1945 until his death in 1980. Though an extraordinary figure, Tito’s experiences can be taken as fairly typical for Yugoslav communists of the interwar period.

Tito fought for Austria-Hungary in 1914 and was initially deployed on the front against Serbia before being transferred to the Carpathian Mountains on the Russian front later that year. By February 1915, Tito was in Eastern Galicia where “he distinguished himself through bravery as the leader of a patrol and was recommended for decoration.”[8] He was taken prisoner by the Russians in May 1915 and remained in the hospital until March 1916. Escaping in autumn 1916, he made it to Petrograd, arriving in the wake of the 1917 February Revolution. After several captures and escapes, he joined the Red Guard in Omsk. When Omsk was captured by the White Guards, he was protected either by the villagers or his rich peasant boss for whom he did odd jobs. At any rate, he managed to avoid imprisonment.

Leaving Omsk in 1919 for Petrograd, Tito heard about the collapse of the Habsburg Empire and the subsequent creation of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes and the rumours of a revolution occurring in that country (which were false). Deciding he needed to partake in the revolutions, Tito was appointed by the Soviets to be the head of the Austro-Hungarian prisoners of war to be repatriated to the new Yugoslav lands. He returned to his native village in 1920 to a country transformed.

In 1920, the Communist Party of Yugoslavia could boast a party membership of 65,000. After assassinating Yugoslavia’s interior minister in 1921, the party was declared illegal by King Aleksandar and virtually disappeared until the 1930s. Initially “following the Moscow anti-Versailles line,” under Tito’s leadership from 1937, the communists were pro-Yugoslav with a Marxist tint.[9] First becoming the secretary of the City Committee of Zagreb in 1928, Tito’s leadership led to some expansion of the party, though it still lacked broad support. With Radić’s assassination in 1929, the party decided that the time was right for a revolution but failed due to a lack of support.

During King Aleksandar’s dictatorial regime, countless communists suspected of clandestine activity were imprisoned, beaten, tortured, and killed. For those fortunate enough to remain alive, the prisons in which they were confined became a “party school” as Marxist literature was smuggled into the jails, radicalising the inmates.[10] Several figures who were imprisoned at this time would play key roles in Yugoslavia during the Second World War and after. These include Tito, Moša Pijade (1890-1957), Aleksandar Ranković (1909-1983), Milovan Djilas (1911-1995), and Edvard Kardelj (1910-1979). All of them seriously studied ideology, politics, economics, and military tactics in preparation for a future revolution. Yet, even in 1934, the communists could not garner enough support in the wake of King Aleksandar’s assassination to hasten a revolution. It was only when Tito assumed leadership of the CPY in 1937 that it finally began to grow. In April 1937, the first congress of the Communist Party of Slovenia took place, followed in August by the founding of the Communist Party of Croatia.

As leader of the CPY, Tito not only oversaw its expansion but also ensured that its members gained valuable experience. In an attempt to keep the Yugoslavs from falling under Soviet control, Tito had many Yugoslavs in the Soviet Union go to Spain to fight for the Republicans in the Spanish Civil War. After party indoctrination in the prisons, the fields of Spain provided the martial experience necessary to wage a guerrilla war. With the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941, the Communist Party of Yugoslavia took up arms against the Nazi invaders. The veterans of the Spanish Civil War “were the ones who took the lead in the Partisan struggle.”[11] Anyone aware of the post-1945 order knows of Tito and the partisans’ importance. This will not be recounted here, except to stress the importance of George L. Mosse’s (1918-1999) concept of wartime “brutalisation.” [12] Indeed, the Great War’s reach extended beyond the years of 1918 and into the decades following even the Second World War.

Conclusion↑

Born of war, it was conflict that the Yugoslav state tried hard to avoid. Its actions in the south of the country – Montenegro, the Sandžak, Macedonia, and Kosovo-Metohija – seem to contradict this assertion. However, it must be remembered that Yugoslavia fits within the trend of other Eastern European countries which emerged in the post-Paris peace conferences environment. Nation building and population engineering were not and could not be separated from each other. The fact that the state was founded on the concept of a “trinomial people,” that is to say a land of and for the Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, meant that anyone who claimed to be something other than any of these groups found themselves outside the bounds of the country’s program. In this light, the disunity of practice and rhetoric of the Yugoslav state and its agents seems less confounding. What the state failed to understand, however, is that such a nationalising program could only radicalise society. Rather than making Yugoslavs, the state made mortal enemies.

Stevan Bozanich, Simon Fraser University

Section Editors: Gunda Barth-Scalmani; Richard Lein

Notes

- ↑ The country was informally and popularly known as Yugoslavia, which it was officially named in 1929 with the advent of King Aleksandar’s dictatorship. This article will follow popular and scholarly convention and use the name Yugoslavia hereafter.

- ↑ Newman, John Paul: Yugoslavia in the Shadow of War. Veterans and the Limits of State Building, 1903-1945, Cambridge 2015, p. 107.

- ↑ Poulton, Hugh: Macedonians and Albanians as Yugoslavs, in: Djokić, Dejan (ed.): Yugoslavism. Histories of a Failed Idea, 1918-1992, London 2003, pp. 115-135, pp. 117-119.

- ↑ For primary documents on the Toplica uprising from the Serbian perspective see Mladenović, Božica (ed.): Toplički Ustanak 1917 [Toplica Uprising 1917]. Zbirka Dokumenata [Documents Collection]. Beograd 2007." Documents Collection

- ↑ Tomasevich, Jozo: The Chetniks: War and Revolution in Yugoslavia, 1941-1945, Stanford 1975, p. 126.

- ↑ Newman, John Paul: War Veterans, Fascism, and Para-Fascist Departures in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, 1918-1941, in: Fascism. Journal of Comparative Fascist Studies 6 (2017), pp. 42-74, p. 43.

- ↑ Cipek, Tihomir: The Croats and Yugoslavism, in: Djokić, Yugoslavism 2003, pp. 71-83, pp. 76-77.

- ↑ Pirjevec, Jože: Tito and His Comrades, Madison 2018, p. 10.

- ↑ Cipek, Croats 2003, p. 77.

- ↑ Pirjevec, Tito 2018, p. 16.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 23.

- ↑ George L. Mosse: Fallen Soldiers. Reshaping the Memory of the World Wars, New York, 1990.

Selected Bibliography

- Adriano, Pino / Cingolani, Giorgio (eds.): Nationalism and terror. Ante Pavelić and Ustashe terrorism from fascism to the Cold War, Budapest et al. 2018: Central European University Press.

- Alcalde Fernández, Ángel: War veterans and fascism in interwar Europe, Cambridge 2017: Cambridge University Press.

- Biondich, Mark: Stjepan Radic, the Croat Peasant Party, and the politics of mass mobilization, 1904-1928, Toronto 2000: University of Toronto Press.

- Djokić, Dejan: Elusive compromise. A history of interwar Yugoslavia, New York 2007: Columbia University Press.

- Djordjević, Dimitrije / Fischer-Galați, Stephen: The Balkan revolutionary tradition, New York 1981: Columbia University Press.

- Drapac, Vesna: Constructing Yugoslavia. A transnational history, Houndmills et al. 2010: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Gerwarth, Robert / Horne, John (eds.): War in peace. Paramilitary violence in Europe after the Great War, Oxford 2012: Oxford University Press.

- Janjetović, Zoran: Dimitrije Ljotić and World War II, in: Istorija 20. veka 36/1, 2018, pp. 93-118.

- Jelavich, Charles / Jelavich, Barbara: The establishment of the Balkan national states, 1804-1920, Seattle 1977: University of Washington Press.

- Lampe, John R. / Mazower, Mark (eds.): Ideologies and national identities. The case of twentieth-century Southeastern Europe, Budapest; New York 2004: Central European University Press.

- Martic, Milos: Dimitrije Ljotic and the Yugoslav National Movement Zbor, 1935-1945, in: East European Quarterly 14/2, 1980, pp. 219-237.

- Newman, John Paul: Yugoslavia in the shadow of war. Veterans and the limits of state building, 1903-1945, Cambridge 2015: Cambridge University Press.

- Newman, John Paul: War veterans, fascism, and para-fascist departures in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, 1918-1941, in: Fascism 6/1, 2017, pp. 42-74.

- Nielsen, Christian Axboe: Making Yugoslavs. Identity in King Aleksandar's Yugoslavia, Toronto et al. 2014: University of Toronto Press.

- Pavlovic, Srdja: Balkan Anschluss. The annexation of Montenegro and the creation of the common South Slavic state, West Lafayette 2008: Purdue University Press.

- Ramet, Sabrina Petra: The three Yugoslavias. State-building and legitimation, 1918-2005, Bloomington 2006: Indiana University Press.

- Sugar, Peter F. (ed.): Native fascism in the successor states, 1918-1945, Santa Barbara 1971: ABC-Clio.

- Svircevic, Miroslav: The new territories of Serbia after the Balkan Wars of 1912-1913. The establishment of the first local authorities, in: Balcanica 44, 2013, pp. 285-306.

- Tomasevich, Jozo: War and revolution in Yugoslavia, 1941-1945. The Chetniks, volume 1, Stanford 1975: Stanford University Press.

- Yeomans, Rory: Visions of annihilation. The Ustasha regime and the cultural politics of fascism, 1941-1945, Pittsburgh 2013: University of Pittsburgh Press.