Introduction↑

In January 1919, the Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA) magazine, Our Own Gazette, proclaimed:

This rallying cry to YWCA members is indicative of the optimism shared by many that the post-war world would not only recover from years of conflict, but be a better place for future generations. This essay will consider some of the transformative elements of post-war society that did enhance the everyday lives of men and women throughout the 1920s. This included political reform with the extension of the parliamentary franchise to millions of men and women in 1918, and again in 1928. The expansion of social welfare provision in areas including housing, health and education improved the lives of many, together with new opportunities for leisure and time away from work. In 1922 the Irish Free State was established, granting independence and dominion status to twenty-six counties of the island of Ireland. Alongside these seismic shifts other, less positive, aspects of post-war life persisted. Racism, gender inequality and poverty continued to blight the lives of families and communities. Within a decade, rising unemployment, race riots and the under-representation of women in paid employment and public life eroded the optimism of the immediate post-war years.

Adjustment: A Land Fit for Heroes?↑

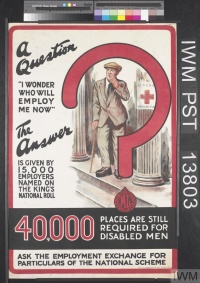

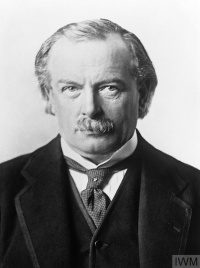

Historians have acknowledged the challenges facing Britain in the wake of the First World War. These included the difficulty of adapting from a war time economy and the ensuing economic crisis as well as Britain’s diminished global standing, in a context transformed from its pre-war certainties by changing gender dynamics, the growth of the Labour Party, increasing trades union militancy and more assertive anti-colonialist movements.[2] Returning demobilised British soldiers between 1918 and 1922 put pressure on the state to oversee a smooth transition back into civilian life.[3] In November 1918 Prime Minister David Lloyd George (1863-1945) famously declared his aim to make Britain “a fit country for heroes to live in”.[4] To this end a number of social policy reforms were introduced to militate against the impact of unemployment, poverty and ill health, and to quell any risk of social unrest. Reforms included a non-contributory Out-of-Work Donation for servicemen and civilians, at a cost of £62 million.[5] The scheme was replaced in 1921 by a new Unemployment Insurance Scheme, which in turn was superseded by the 1927 Unemployment Insurance Act.[6]

Providing homes fit for heroes was a second key priority. The wartime Tudor Walters Committee on Housing Standards introduced new minimum requirements for the design of post-war council housing. Hearing evidence from the Women’s Labour League (affiliated to the Labour Party) the committee’s report included recommendations made on behalf of working-class women. As a consequence, the 1919 Addison Housing and Town Planning Act resulted in the building of 170,000 new council houses. These adhered to a higher design standard with more space, light, parlours and running water, features insisted upon by the Women’s Labour League.[7] The 1924 Wheatley Housing Act, which allowed central government to provide subsidies to public housing, further increased house building and by 1933 over half a million new council homes had been built. For those who could afford the higher rents and mortgages, the opportunity to live in modern homes on new suburban housing estates improved their lives considerably. Those less well-off remained trapped in overcrowded inner-city slums or in sub-standard rural homes.[8]

In response to the influenza epidemic of 1918-1919, a new Ministry of Health was set up, although this did not signify a revolution in state-subsidised healthcare.[9] Yet some improvements were made during the 1920s, for example the passing of the 1918 Maternity and Child Welfare Act. Motivated by a desire to safeguard ”national efficiency”, the act encouraged but did not require local authorities to provide subsidised healthcare to mothers and their babies.[10] However, access to birth control information continued to be denied to working-class women attending publicly funded clinics, although some women were able to obtain free advice at voluntary clinics, for example those set up by Marie Stopes (1880-1958).[11] Despite these changes, healthcare provision was only available to those who could pay or limited to workers eligible for free healthcare under the pre-war 1911 National Insurance Scheme.[12]

More radical reform was forthcoming with the passing of the 1918 Education Act. This resulted in the school-leaving age being raised from twelve to fourteen years and elementary school fees were abolished. For those aged fourteen to eighteen a new opportunity to remain in part-time “continuation day” classes was introduced. Local authorities were encouraged to expand school medical inspections along with nursery schools and special needs education.[13] Overall social policy reforms introduced during the 1920s, limited as they were, did facilitate a mostly peaceful adjustment from wartime conditions.[14] These reforms reflected a greater willingness by the state to take responsibility for the welfare of citizens, a principle that would shape public policy in the following decades.

Post-war adjustment was also evident with regards to the 1920s political landscape. One significant change was the demise of the Liberal Party in parliamentary politics, in contrast to the rising popularity of the Labour Party. Labour formed its first government in 1924, followed by a second period in office from 1929-1931. This dramatic shift in the party system continued well beyond the 1920s with conservative and labour governments dominating British politics for the remainder of the century.

Ireland: Wars and Independence↑

The immediate post-war years in Ireland were characterised not by adjustment, but by violence. The failed 1916 Easter Rising reignited demands for an independent Ireland that went beyond the model of regional government, as set out in the 1914 Home Rule Bill.[15] This led to the outbreak of the War of Independence in 1919, ended by the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty in December 1921. Under the terms of the treaty, a twenty-six county Irish Free State would be established as a self-governing dominion within the British Empire. Not only did this signify a separation from empire; it also confirmed the partition of Ireland. A six-county, unionist-majority Northern Ireland State, remaining part of the United Kingdom, was established in May 1921 with its own devolved government. The approval of the Anglo-Irish Treaty in Dáil Éireann (Irish parliament) sparked a bitter civil war lasting into 1923. Taking a pro or anti treaty stance spilt the ruling Sinn Féin party with opposing sides represented by the pro-treaty Provisional Government, led by Michael Collins (1890-1922) at war with the Irish Republican Army, who rejected the treaty in favour of a united Ireland. The war ended in 1923 followed by the election of the new pro-treaty Cumann na nGaedheal government. In the midst of hostilities, the 1922 Irish Free State Constitution was enacted, confirming the new state’s commitment to popular sovereignty and democratic values. This included the extension of universal suffrage to all citizens aged twenty-one, six years ahead of the rest of the United Kingdom.[16]

Despite a strong commitment to democratic ideals, the formative years of the Irish Free State were marred by the legacy of war, political division, and social conservatism.[17] The trauma inflicted by the Anglo-Irish War and the civil war cast a long shadow. One manifestation of this was a reluctance to fully engage with the nation’s violent past. It is only in recent years that the extent of wartime sexual violence has been acknowledged.[18] This omission is in stark contrast to the prominence given to women’s contribution to the national struggle. Indeed, it was Constance Markievicz (1868-1927), serving a prison sentence for her role in the 1916 rising, who in December 1918 became the first woman elected to the British parliament (as a member of Sinn Féin, she refused to take up her seat).[19] Five female TDs (members of parliament) were elected to the Dáil in 1923. In Northern Ireland, the Ulster Women’s Unionist Council promoted male rather than female candidates and prioritised the unionist cause over women’s rights. Nevertheless, two women were elected to the first Northern Ireland parliament.[20]

In the Irish Free State hopes that gender equality would be achieved were quickly dashed. Over the course of the 1920s the Cumann na nGaedheal government introduced a series of measures that impacted negatively on women’s lives. These included: the 1924 and 1927 Juries Acts, which limited the right of women to sit on juries, bans on divorce and birth control and a public service marriage bar.[21] Such conservatism reflected the dominance of the Roman Catholic Church over Irish political and social life in what was already a traditional rural society. This dominance of Catholic social teaching extended beyond politics to other areas of life. Hollywood films were banned, women were expected to dress and behave in a modest manner and in 1929 the Censorship of Publications Act was enacted.[22] Despite this hostile environment, women’s organisations, including veterans of the Irish women’s suffrage movement, continued to campaign for women’s rights throughout the 1920s. These groups, for example the National Council of Women and the Irish Women’s Workers’ Union, were successful in sustaining the women’s movement during these years.[23]

Divided Society: Gender, Class and Race↑

In Great Britain, the 1918 extension of the parliamentary franchise to all men (regardless of property) aged twenty-one (an additional 7.7 million) and to women over thirty who met the required property qualifications or were university graduates (8.5 million) was a significant and symbolic moment. It acknowledged the sacrifice made by working-class men serving in the First World War. It also answered the demand of the women’s suffrage movement, albeit only partially, for the right of women to vote in parliamentary elections.[24] In December 1919 Nancy Astor (1879-1964) became the first woman to take her seat in the House of Commons, and ten years later the number of women MPs (members of parliament) increased to fourteen following the 1929 general election.[25] Outside Westminster women continued to be active within the three main political parties, which they could now join as full members. By the late 1920s the Labour Party had 300,000 women members, the Conservative Party one million women and the Liberal Party 100,000 women within their ranks. Women remained active in local government, as they had done since the late 1800s, with 754 female local councillors elected by 1923 alongside 2,323 Poor Law Guardians.[26]

As in Ireland, the extension of the franchise to women did not bring about gender parity. Nevertheless, legislative reforms were introduced in the early 1920s, which did improve the position of women and reflected the influence women voters had on parliamentary politics and legislative reform. The 1923 Matrimonial Causes Act, the 1919 Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act and the 1925 Guardianship of Infants Act provided women with greater protection within family and employment law. Despite these reforms significant obstacles remained for women who sought to engage in paid work. A public service marriage bar required women in the civil service and teaching to resign on marriage. Women were also subject to lower pay than men and for significant numbers of working-class women domestic service remained the only employment option.[27]

The women’s movement in the 1920s expanded to include former suffrage societies, feminist pressure groups and large voluntary associations for women.[28] Groups including the National Union of Societies for Equal Citizenship, the Six Point Group, Women’s Institutes and the YWCA worked in different ways to support women and campaign for women’s rights. Included among their many demands were: equal pay, family allowances paid to mothers, adequate healthcare and the equal franchise, finally granted to women in 1928.[29] Women also made a major contribution to the interwar peace movement, both nationally and internationally, demonstrating that women as voters were informed and active citizens in post-war Britain.[30]

Inequality remained across class divides in post-war Britain. For working-class communities dependent on declining export industries, for example in Wales, Scotland and the northeast, life became more difficult as these areas had higher levels of poverty than in the rest of the UK. This situation worsened from 1921 when discontent about increased taxation resulted in the slashing of public spending in housing and education, a measure known as “Geddes axe”.[31] To make matters worse, incomes began to fall for those employed in traditional industries and the 1926 General Strike failed to protect miners from further pay cuts. Moreover, increasing levels of unemployment from 1929 onwards further extended the gap between rich and poor. Abject poverty and deprivation persisted. In the late 1920s it was estimated that 16 percent of children in east London lived in extreme poverty.[32] In contrast, the middle class expanded and became better off during the 1920s. New job opportunities in the civil service, banking and the professions enabled this growth and fuelled consumer spending, for example on home and car ownership, as well as on holidays and leisure activities.[33]

Racism remained deeply entrenched within post-war British society. Irish, Jewish, Chinese, Asian and Black communities continued to experience racial discrimination, just as they had done for centuries before.[34] A wave of antagonism against Asian and African ex-service men and seafarers erupted between April and June 1919 in a number of port cities including Liverpool, Cardiff, Glasgow and London. Here gangs of white men engaged in street attacks resulting in five deaths, numerous injuries and damage to property.[35] The violence was blamed on perceived competition for jobs and housing but also revealed deep-seated racial prejudice. In particular, white supremacist views underpinned the anger of white men enraged by interracial relationships between local women and men of colour.[36] In the wake of these racially motivated attacks the primary response of the authorities was to remove “either by internment or repatriation, the black population” thereby laying the blame for the disorder squarely at the feet of the victims of the attacks.[37] The Black community in Britain responded by speaking out in the press and setting up groups including the West African Students’ Union (1925) and the League of Coloured Peoples (1931).[38] Nevertheless, the spectre of racism would loom large in British society throughout the interwar years and beyond.

Leisure: The “Jazz Age” and the “Roaring Twenties”↑

The violence meted out to men of colour in 1919 was in stark contrast to the popularity of African-American musicians and performers who visited Britain during the 1920s. The decade is often referred to as the “jazz age” or the “roaring twenties”. These monikers stem from the clubs, theatres and music venues popular among the upper class and “fast set”, made up of royalty, film stars and sports celebrities.[39] The period is also synonymous with ”flappers”, young single women characterized by bobbed hair, shorter skirts, cigarette smoking and general joie de vivre. The Original Dixieland Jazz Band (made up of white Americans) brought New Orleans style jazz to the UK while the Southern Syncopated Orchestra (representing African American, West Indian and Black British musicians) and the jazz great Louis Armstrong (1901-1971), were frequent performers at nightclubs and society parties.[40] In 1926 the African-American performer Florence Mills (1896-1927) and her troupe, “The Blackbirds”, played at the London Pavilion, becoming an instant hit.[41] Despite the modernity of these new forms of entertainment, an underlying puritanism remained entrenched within post-war society. One example of this was the 1928 scandal and obscenity trial surrounding the publication of Radclyffe Hall’s (1880-1943) The Well of Loneliness, which depicted a lesbian love affair.[42]

Away from the clubs and theatres in metropolitan areas, men and women engaged in a wide range of leisure pastimes throughout the 1920s. These included spectator sports such as football, cricket and greyhound racing. Horse racing grew in popularity, aided by the opportunities for on and off course betting. Cinema going became ever more popular, particularly among women, captivated by Hollywood movies offering a taste of a more glamorous life, at an affordable price.[43] Cycling, rambling and folk dancing were popular pursuits during these years, especially for those living in rural areas.[44] One major development from 1922 was the advent of BBC Radio, with its mix of news, music and drama, all to be enjoyed from the comfort of home.[45]

Conclusion↑

Hope characterised the immediate post-war years in Great Britain. Hope manifested itself in the prospect of a more equitable, democratic and peaceful world, a ”land fit for heroes”. The 1920s did deliver on this sense of optimism, at least in the short term. The expansion of social welfare and the provision of healthcare and education signified a state that recognised its growing responsibility for the welfare of its citizens. No doubt this realisation was motivated by the need to suppress social unrest and to satisfy the demands of a significantly enlarged electorate. For members of the middle-class and upper working-class, increased standards of living, more leisure time and new suburban homes meant there was much to be optimistic about.

In Ireland, the “terrible beauty”[46] born at Easter 1916, resulting in the creation of the Irish Free State, signalled a direct challenge to centuries of colonial rule and the authority of the British Empire. This gave hope to other nations seeking to break away and would lead to new challenges to empire in the years to come. However, the violent birth of the Irish nation, the consequences of partition and the dominance of the Roman Catholic Church tempered the hopes of some who had long dreamed of independence from Britain.

The social, economic and political changes in Great Britain and Ireland after the Great War were dramatic. Nonetheless, poverty, racism and gender inequality continued to limit life chances for a significant number of citizens. By the end of the 1920s these fault lines were becoming more apparent. Social divisions intensified during the 1930s, stimulated by a global economic crisis and record unemployment, and all changed once again with the outbreak of a second world war.

Caitríona Beaumont, London South Bank University

Section Editor: Adrian Gregory

Notes

- ↑ Our Own Gazette, January 1919, p. 5.

- ↑ Bland, Lucy: White Women and Men of Colour. Miscegenation Fears in Britain After the Great War, in: Gender & History 17 (2005), p. 30.

- ↑ Barry, Gearóid: Demobilization, in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War, ed. by Ute Daniel, Peter Gatrell, Oliver Janz, Heather Jones, Jennifer Keene, Alan Kramer, and Bill Nasson, issued by Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin 2018-12-04. DOI: 10.15463/ie1418.11323.

- ↑ Speech in Wolverhampton, 24 November 1918. Cited in Thane, Pat: Divided Kingdom. A History of Britain, 1900 To The Present, Cambridge 2018, p. 68.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 74.

- ↑ Thane, Divided Kingdom 2018, pp. 70-115.

- ↑ Caroline Rowan: Women in the Labour Party, 1906-20, in: Feminist Review 12 (1982), pp. 74-91.

- ↑ Burnett, John: A Social History of Housing 1815-1985, London 1986.

- ↑ Thane, Divided Kingdom 2018, p. 69.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Marie Stopes opened her first birth control clinic in London in 1921. From 1930 local authority clinics were permitted to provide limited birth control advice to married women. See Fisher, Kate: Birth Control, Sex and Marriage in Britain, 1918-1960, Oxford 2006 and Beaumont, Caitríona: Housewives and Citizens. Domesticity and The Women’s Movement in England, 1928-64, Manchester 2015, pp. 80-87.

- ↑ Thane, Pat: The Foundations of the Welfare State, London 2013, pp. 119-210.

- ↑ Thane, Divided Kingdom 2018, p. 70.

- ↑ In 1919 riots did break out in a number of towns and cities across the UK including Glasgow and Luton. See Todd, Selina: The People. The Rise and Fall of the Working Class, London 2014, pp. 30-45.

- ↑ Jackson, Alvin: Home Rule. An Irish History 1800-2000, Oxford 2003.

- ↑ Beaumont, Caitríona: Women, Citizenship and Catholicism in the Irish Free State, 1922-1948, in: Women’s History Review 6/4 (1997) pp. 563-585.

- ↑ Ferriter, Diarmaid: The Transformation of Ireland 1900-2000, Dublin 2004. See also Grayson, Richard S.: Ireland, in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War, ed. by Ute Daniel, Peter Gatrell, Oliver Janz, Heather Jones, Jennifer Keene, Alan Kramer, and Bill Nasson, issued by Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin 2014-10-08. DOI: 10.15463/ie1418.10473.

- ↑ See Ryan, Louise: Drunken Tans. Representation of Sex and Violence in the Anglo Irish War (1919-1921), in: Feminist Review 66 (2000), pp. 73-94, Connolly, Linda: Sexual Violence in the Irish Civil War. A Forgotten Crime?, in: Women’s History Review 30/1 (2021), pp. 126-143. See also Connolly, Linda (ed.): Women and the Irish Revolution. Feminism, Activism, Violence, Dublin 2020.

- ↑ Pašeta, Senia: Peace and Protest in Ireland. Women’s Activism in Ireland, 1918-1937, in: Diplomacy & Statecraft 31/4 (2020), pp. 672-696. See also Ward, Margaret: Unmanageable Revolutionaries. Women and Irish Nationalism, London 1989.

- ↑ Beaumont, Caitríona: After the Vote. Women, Citizenship and the Campaign for Gender Equality in the Irish Free State (1922-1943), in: Ryan, Louise / Ward, Margaret (eds.): Irish Women and The Vote. Becoming Citizens, Dublin 2018, pp. 231-250. See also Urquhart, Diana / Taillon, Ruth: Women and the State in Northern Ireland, 1920-60, in: O’Dowd, Mary (ed.): Field Day Anthology. Irish Women’s Writing and Traditions, Cork 2002, pp. 353-372.

- ↑ Beaumont, Women, Citizenship and Catholicism 1997, pp. 563-568.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Beaumont, Caitríona / Clancy, Mary / Ryan, Louise: Networks as “Laboratories of Experience”. Exploring the Life Cycle of the Suffrage Movement and its Aftermath in Ireland 1870-1937, in: Women’s History Review 29/6 (2020), pp. 1054-1074.

- ↑ Purvis, June / Hannam, June (eds.): The British Women’s Suffrage Campaign. National and International Perspectives, London 2020.

- ↑ In 1929 601 male MPs were elected. See Reeves, Rachel: Women of Westminster. The MPs Who Changed Politics, London 2019 and Cowman, Krista: Women in British Politics, c. 1689-1979, London 2010.

- ↑ Thane, Pat: What Difference did the Vote Make? Women in Public and Private Life in Britain since 1918?, in: Historical Research 76/192 (2003), pp. 268-285 and Thane, Divided Kingdom 2018, p. 80.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 81-83.

- ↑ Law, Cheryl: Suffrage and Power. The Women’s Movement, 1918-1928, London 1997.

- ↑ Beaumont, Housewives and Citizens 2015.

- ↑ See Beaumont, Caitríona: Women’s Organisations, Active Citizenship, and the Peace Movement. New Perspectives on Female Activism in Britain, 1918-1939, in: Diplomacy & Statecraft 30/4 (2020), pp. 697-721.

- ↑ Thane, Divided Kingdom 2018, p. 76.

- ↑ Gazeley, Ian: Poverty in Britain, 1900-1965, London 2003, p. 82.

- ↑ Thane, Divided Kingdom 2018, pp. 104-108. See also McKibbin, Ross: Classes and Cultures. England 1918-51, Oxford 1998.

- ↑ See Tabili, Laura: Global Migrants, Local Culture. Natives and Newcomers in Provincial England, 1841-1939, London 2011, Fryer, Peter: Staying Power. The History of Black People in Britain, London 1984 and Jenkinson, Jacqueline: Black 1919. Riots, Racism and Resistance in Imperial Britain, Liverpool 2019.

- ↑ Bland, White Women and Men of Colour 2005, p. 34. See also Christian, Mark: An African-Centered Approach to the Black British Experience With Special Reference to Liverpool, Journal of Black Studies 26/3 (1998), pp. 291-308, Rowe, Michael: Sex, “Race” and Riot in Liverpool, 1919, in: Immigrants & Minorities 19/2 (2000), pp. 53-70.

- ↑ Bland, White Women and Men of Colour 2005, pp. 29-61.

- ↑ Rowe, Sex, “Race” and Riot 2000, p. 65.

- ↑ Fryer, Staying Power 1984, pp. 327-334. See also Donlon, Anne: “A Black Man Replies”. Claude McKay’s Challenge to the British Left, in: Lateral. Journal of the Cultural Studies Association 5/1 (2016), n.p.

- ↑ Thane, Divided Kingdom 2018, pp. 105-106.

- ↑ See Tackley, Catherine: The Evolution of Jazz in Britain, 1880-1935, London 2017 and Jackson, Kevin: Constellation of Genius. 1922, Modernism and all that Jazz, London 2013.

- ↑ Bressey, Caroline / Romain, Gemma: Staging Race. Florence Mills, Celebrity, Identity and Performance in 1920s Britain, in: Women’s History Review 28/3 (2019), pp. 380-395.

- ↑ Hall, Lesley: Sex, Gender and Social Change in Britain Since 1880, London 2013, pp. 85-101.

- ↑ Langhamer, Claire: Women’s Leisure in England, 1920-60, Manchester 2000.

- ↑ Snape, Robert: Leisure, Voluntary Action and Social Change in Britain, 1880-1939, London 2018, p. 64 and 102.

- ↑ Thane, Divided Kingdom 2018, pp. 110-111.

- ↑ Yeats, W.B. 'Easter, 1916', The Collected Poems of W.B. Yeats, London, 1994, p. 152.

Selected Bibliography

- Beaumont, Caitríona: Housewives and citizens. Domesticity and the women's movement in England, 1928-64, Manchester 2016: Manchester University Press.

- Ferriter, Diarmaid: The transformation of Ireland 1900-2000, Dublin 2010: Profile Books.

- Fisher, Kate: Birth control, sex and marriage in Britain 1918-1960, Oxford 2011: Oxford University Press.

- Fryer, Peter: Staying power. The history of black people in Britain, London 1984: Pluto Press.

- Gazeley, Ian: Poverty in Britain, 1900-1965, London 2017: Red Globe Press.

- Gottlieb, Julie V. / Toye, Richard: The aftermath of suffrage. Women, gender, and politics in Britain, 1918-1945, Basingstoke 2013: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Langhamer, Claire: Women's leisure in England, 1920-60, Manchester; New York 2000: Manchester University Press.

- Law, Cheryl: Suffrage and power. The women's movement, 1918-1928, London 1997: I.B. Tauris.

- McKibbin, Ross: Classes and cultures. England, 1918-1951, Oxford 2011: Oxford University Press.

- Purvis, June / Hannam, June (eds.): The British women's suffrage campaign. National and international perspectives, London 2020: Routledge.

- Ryan, Louise / Ward, Margaret (eds.): Irish women and the vote. Becoming citizens, Dublin 2018: Irish Academic Press.

- Sugg Ryan, Deborah: Ideal homes. Uncovering the history and design of the interwar house, Manchester 2020: Manchester University Press.

- Tabili, Laura: Global migrants, local culture. Natives and newcomers in provincial England, 1841-1939, Basingstoke 2011: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Tackley, Catherine: The evolution of jazz in Britain, 1880–1935, London 2017: Routledge.

- Thane, Pat: The foundations of the welfare state, London 2013: Routledge.

- Thane, Pat: Divided kingdom. A history of Britain, 1900 to the present, Cambridge 2018: Cambridge University Press.

- Todd, Selina: The people. The rise and fall of the working class, London 2014: John Murray.