Before the First World War↑

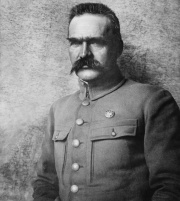

Józef Piłsudski (1867-1935) was a descendant of the Polish noble family from Lithuania. He became politically active when he was a student, involving himself with the socialist movement. Repeatedly imprisoned by Russian authorities, Piłsudski was sent to Siberia from 1887 to 1892. In 1893, he became a member of the Polish Socialist Party (PPS).

In 1901 Piłsudski ran away from Russian prison and emigrated to Austria-Hungary. During the Russo-Japanese War he tried to convince the Japanese to support Polish aspirations. To that end, he traveled to Tokyo in the summer of 1904; there, he offered to supply Japan with intelligence and proposed to create a Polish Legion from Polish soldiers taken as prisoners of war by the Russian army. In exchange he gained Japanese financial and technical support for the PPS. By October 1905 Piłsudski achieved complete control of a paramilitary unit of the PPS (Combat Organization). It became his power base in the party.

The 1905 Revolution was a disappointment for Piłsudski because he realized it would be virtually impossible to transform a revolutionary movement into a national insurrection. His resolve to win Polish independence through uprisings and his decision to boycott the elections to the First Duma led to tensions within the PPS. Finally, in 1906, the party split between Piłsudski’s “Elders” (Starzy) or “Revolutionary Faction” (Frakcja Rewolucyjna) and the “Youngsters” (Młodzi), also known as “Moderates” (Frakcja Umiarkowana) or “Left Wing” (Lewica), who believed that priority should be given to cooperation with Russian revolutionaries.

In 1907 the Association for Active Struggle (Związek Walki Czynnej) was created in Lwów (Lviv). Piłsudski transformed it into an independent paramilitary body. In December 1912 Piłsudski was appointed chief commandant of all Polish military and paramilitary organizations in Galicia. From 1910 to 1914, Piłsudski created the Riflemen’s Associations (Związki Strzeleckie) in Galicia to conduct military training. By 1914 they numbered 12,000 men.

The First World War↑

After the official outbreak of the war between Austria-Hungary and Russia on 6 August 1914, the First Cadre Company (so named to signify it would be a unit for future Polish forces) crossed the border and marched to Kielce. Piłsudski wanted to take over territories evacuated by Russians and hoped to break through to Warsaw and spark a national uprising. On 12 August 1914, Piłsudski's forces took Kielce, but the populace was more reluctant than he expected. Russians decided to defend Warsaw, preventing him from executing his plans. The Austro-Hungarian military, enraged by Piłsudski's wayward actions, demanded he join his forces with the Austro-Hungarian Landsturm (militia - a reserve force intended to provide replacements for the first line units).

On 16 August the Supreme National Committee (Naczelny Komitet Narodowy) was created and the Vienna government agreed to create Polish Legions. Piłsudski became a commander of the first regiment of the Legions. At the same time he started to develop the Polish Military Organisation (Polska Organizacja Wojskowa), an underground army designed to perform espionage and sabotage missions in the territories controlled by Russia.

On 10 September Piłsudski's forces left Kielce. Piłsudski fought against Russian forces between Nowy Korczyn (in northern Galicia) and Dęblin on the Vistula River. By the beginning of November he was surrounded by Russian forces and had to retreat to Kraków. On 15 November he was promoted to the rank of brigadier.

In December the first regiment was transformed into the First Brigade of Polish Legions. From 22 November to 5 December, his brigade fought and won its first battle against the Russians at Łowczówek. Piłsudski and the First Brigade participated in the Austro-Hungarian offensive, a battle at Konary from 16–23 May 1915. On 3 August he reached Lublin. By that time, Piłsudski realized that the population of Congress Poland was hostile toward the Central Powers. Hence, he started to distance himself from those nations. He also decided that the Polish Legions should be, in some foreseeable future, disbanded, while the underground Polish Military Organisation should develop further.

During the autumn of 1915 all brigades of the Polish Legions were moved to the northern part of Volyhnia. In April 1916 the Colonels Council was created at Piłsudski's initiative, showing his distrust of official command of the Legions.

In the summer of 1916 the Legions saw their most intense fighting. In the Battle of Kostiuchnówka (4–6 July 1916), the Legions delayed a Russian offensive. After this battle Piłsudski demanded that the Central Powers issue a guarantee of independence for Poland; when they declined on 26 July 1916, he offered a resignation accepted on 26 September. This led to a crisis in the Legions. Their breakup was only avoided because of the 5 November 1916 Proclamation of the Central Powers, which promised to create an independent Poland. On 6 December Piłsudski entered the Provisional Council of State (Tymczasowa Rada Stanu), the temporary Polish government created by the Central Powers in Warsaw, as the chief of military commission.

The Central Powers’ disregard for the Provisional Council caused Piłsudski to drift away. He took an increasingly uncompromising stance after the Russian Revolution in early 1917; he even considered going to Russia to take over command of the Polish Military Forces created there. He finally decided against such drastic action, still hoping for some kind of understanding with the Central Powers. However, the rising anti-German sentiments in Congress Poland convinced him that he needed to break with the Central Powers.

On 10 April 1917 Austria-Hungary transferred the Polish Legions to the command of Hans Hartwig von Beseler (1850–1921), naming him commander in chief of the Polnische Wehrmacht. This led to the so-called “Oath Crisis” in July 1917, when Polish soldiers from Russian territories were forced to take the oath of allegiance to the German and Austro-Hungarian emperors. Piłsudski forbade Polish soldiers to swear this oath. He also ordered the Polish Military Organisation to start a campaign against German troops. This was his final act of divorce from the Central Powers. On 21–22 July 1917 Piłsudski was arrested, and on 2 August he was imprisoned in Magdeburg. Most of the Polish units declined to take the oath and were disbanded, and the soldiers were either interned or incorporated into the Austro-Hungarian army.

Piłsudski’s imprisonment greatly enhanced his reputation among Poles. He became a symbol of determined struggle for independence.

Beginning of Independence↑

On 8 November 1918 Piłsudski was released from Magdeburg, and he returned to Warsaw two days later. On 11 November 1918 the Regent Council appointed Piłsudski commander in chief of Polish forces, and only three days later the council dissolved and transferred its full powers onto him. Various provisional governments - that of Ignacy Daszyński (1866–1936) in Lublin, or the Polish Liquidation Committee in Kraków - and military organisations accepted Piłsudski as a leader of the state.

On 18 November Jędrzej Moraczewski (1870–1944), a close confidant of Piłsudski and a member of the PPS, formed the first Polish government. On 22 November Piłsudski officially received the title of provisional chief of state (Naczelnik Państwa). His main concern was the creation of a Polish army to help safeguard Polish independence.

Piłsudski was aware that the western powers did not trust him, so he made an agreement with Roman Dmowski (1864–1939), the head of the Polish National Committee (Komitet Narodowy Polski) in Paris, who the French recognized as the official Polish representation. Piłsudski was to be provisional chief of state and commander in chief, while Dmowski and Ignacy Jan Paderewski (1860–1941) represented Poland at the Paris Peace Conference.

Realizing that German and Russian revisionism would threaten not only Poland, but also other newly emerged states in central and eastern Europe, Piłsudski proposed the idea of an “Intermarum”: a federation of Poland, the Baltic States, Belarus, and Ukraine. His plans met with opposition from most of the prospective member states. In place of an eastern European alliance, a series of border conflicts with Poland’s neighbours emerged, which shaped relations in the region for the next twenty years.

Polish-Soviet War (1919–1921)↑

The main problem facing the revived state was the need to create stable borders. This led to a series of conflicts, of which the war with Bolshevik Russia was the most serious. Piłsudski knew that the Bolsheviks were no friends of an independent Poland, but he also realized that they were less dangerous for Poland than the so-called White Russians were. Given the situation, Piłsudski declined to participate in an intervention in Russia. Only the Bolshevik westward offensive of 1918–1919 caused Piłsudski to react. On 21 April 1920, he signed a military alliance with Ukrainian leader Symon Petliura (1879–1926). On 25 April Polish and Ukrainian forces started the Kiev Offensive against Soviet forces in Ukraine, and on 7 May 1920 they captured Kiev; still, Petliura was unable to establish an independent Ukrainian state.

This led to the largest of the military conflicts for the newly independent state. The victory in the Polish-Soviet War, and especially the battle of Warsaw (August 1920), was crucial for the creation of Piłsudski’s legacy.

Retirement, Coup d’Etat, and the Rule of Sanation↑

In December 1922, the Polish National Assembly elected Gabriel Narutowicz (1865–1922) to the presidency, and Piłsudski officially transferred his powers as chief of state to him. Two days later, on 16 December 1922, Narutowicz was assassinated. This was a major shock for Piłsudski, challenging his belief that Poland could function as a democracy. After 1922 Piłsudski resigned from all of his official positions and retired to his villa in Sulejówek, just outside Warsaw. There he took time to write a series of political and military memoirs. His supporters repeatedly asked him to return to politics, and he started to create a new power base organised around former soldiers of the Legions and members of the Polish Military Organisation.

In May 1926 Piłsudski decided to organise armed protest to force the issue of transferring emergency powers to him. On 12–14 May 1926 it turned into the May Coup, which was supported then by left-wing parties. On 31 May the Sejm elected Piłsudski president of the Republic, but he declined the office. Instead, his protégé, Ignacy Mościcki (1867–1946), took office as president. Formally, apart from two terms as prime minister (1926–1928 and 1930), Piłsudski was just a minister of military affairs, general inspector of the armed forces, and chairman of the war council between 1926 and 1935. His leadership was sometimes called a “quasi-dictatorship” or a “semi-dictatorship.”

Piłsudski’s named his authoritarian regime “Rule of Sanation” after the latin sanatio, meaning “healing”. With time he had become increasingly disillusioned with democracy, which resulted in him wanting to stabilize the political, social, and economic situation by strengthening the executive branch of government. Eventually, he even wanted to transform the parliamentary system into a presidential one. He gradually transferred real rule to his associates and concentrated his own efforts on the development of the army and strengthening Poland’s international stance. He began to look for an alliance with western powers: France, the United Kingdom, and neighbours such as Romania, Hungary, and Latvia. Piłsudski also decided to improve Poland’s relationships with Germany and the USSR. In 1932 Poland signed the Non-Aggression Pact with the USSR and two years later did the same with Germany.

Piłsudski died on 12 May 1935 from liver cancer. He was buried in the Wawel Cathedral Crypt, a place where the remains of kings and national heroes were buried. His heart was interred in his mother’s grave at the Rasos Cemetery in Vilnius.

Michał Leśniewski, University of Warsaw

Section Editor: Piotr Szlanta

Selected Bibliography

- Dziewanowski, Marian Kamil: Joseph Piłsudski. A European federalist, 1918-1922, Stanford 1969: Hoover Institution Press.

- Garlicki, Andrzej: Józef Piłsudski, 1867-1935, Warsaw 1988: Czytelnik.

- Jedrzejewicz, Waclaw: Józef Piłsudski 1867-1935, London 1986: Polska Fundacja Kulturalna.

- Pilsudska, Aleksandra / Ellis, Jennifer: Pilsudski, a biography by his wife, New York 1941: Dodd, Mead.

- Świętek, Ryszard: Lodowa ściana. Sekrety polityki Józefa Piłsudskiego 1904-1918 (An ice wall. Secrets of the policy of Józef Piłsudski 1904-1918), Kraków 1998: Platan.