The Pan-German League before the First World War↑

The Pan-German League (1891-1939) embraced a brand of nationalism that called for the uncompromising unification of all Germans into an ethnically and politically homogeneous German Empire. Several founding members of the league came from the German colonial movement of the 1880s. Close connections with the language movement (Sprachbewegung) in Germany and Austria signaled the league’s aspirations to use language as a cultural marker for ethnic belonging. The Pan-German concerns over the limitations of the German nation-state of 1871, the challenges of transnational migration and the ethnic complexity of German society were to be solved by a comprehensive social rearrangement. 20 million ethnic Germans lived outside of Germany in other nation-states.

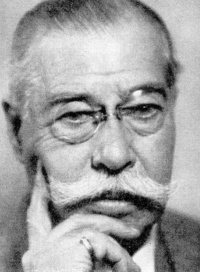

Foreign expansion of the German Empire, ethnic homogenization, and political reform were all elements of the comprehensive program of the Pan-German League, which Heinrich Claß (1868-1953) had laid out in a series of publications since he became chairman in 1908. Claß demanded the suppression of religious and ethnic minorities in imperial Germany (in particular Jews and Slavs), and the political suppression of social democracy, left-liberalism, and the Catholic Center Party as domestic “enemies of the empire”.

Pan-German War Aims of 1914↑

For the Pan-Germans, the war represented an opportunity to realize their domestic and foreign program: enforcement of the Burgfrieden, enforced cultural homogenization, and territorial expansion. The war aims that Claß put before the executive committee on 28 August 1914 were far-reaching. They included the realization of German domination in Central Europe and demands that the war should bring about the acquisition of land and the unification of ethnic Germans in Central Europe. The expulsion of people from their homelands (“land without people”), as demanded by both Claß and his deputy chairman Konstantin von Gebsattel (1854-1932), signaled a radicalized approach towards German ethnic politics.

After the meeting of the executive council in August 1914, Claß put together an extended list of war aims. Although disagreements remained within the league over the priority of Western or Eastern Europe in the program, it specified plans for a German-dominated Mitteleuropa in which the Netherlands would become a closer partner of Germany, Luxembourg would be linked to the empire, and Belgium would be occupied and divided between the Walloon and the Flemish communities. Territorial annexations in the industrialized areas in north-eastern France were to complement plans for German control of French territory up to the English Channel. France and Great Britain were to be weakened and their influence around the world was to be reduced to a minimum. Poland was to be separated from Russia to realize its “affiliation” to the German Empire. In addition, the Baltic provinces (especially Courland, Livonia, and Estonia) were to be annexed to Germany in order to allow for comprehensive German settlement plans after the war. Eastern European Jews were to be resettled outside of German-occupied territories and ethnic Germans from the Russian Empire were to be settled in German lands in the east. Zionism was to be supported by the German government in order to facilitate the settlement of European Jews in Palestine, which Germany’s war ally, the Ottoman Empire, would assist in.

War Experiences↑

Claß faced the restrictions of government censorship, which remained effective until November 1916. The prohibition of the circulation of his war aims program and two searches of his home in Mainz revealed the determinedness of the government of Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg (1856-1921) to silence Pan-German propaganda (the censorship of Claß’ war aims pamphlet was lifted in May 1917). The “Alldeutsche Blätter” were subject to preventive censorship starting in January 1915, and surveillance was placed on Claß’ outgoing mail in March 1915. The estrangement of the Pan-German League from Wilhelm II, German Emperor (1859-1941) and Bethmann Hollweg continued during the war. The appointment of a series of four different chancellors after Bethmann Hollweg left office in July 1917 only added to Pan-German perceptions of the continuing loss of order, authority, and culture. The league intensified its propaganda for a military dictatorship under the leadership of Paul von Hindenburg (1847-1934) and Erich Ludendorff (1865-1937) from the Third Supreme Command.

The Pan-German League lost several activists to war recruitment and war casualties. During the war, Claß enforced the centralization and ideological synchronization of the league’s national leadership. This process, perplexingly, tended to broaden and weaken the league’s membership composition on the local level. Although the Pan-German League increased its membership from 17,000 in 1914 to 37,000 in the summer 1918, several local chapters “decayed” during the war.

Ideological and Political Radicalization 1917/1918↑

In 1917-1918, the Pan German League became increasingly anti-Semitic. The radicalisation of its anti-Semitism was intended to transcend the conflicts on the home front to blame “un-German” enemies for the deepening of domestic fragmentation and to mobilize broad support for a “Siegfrieden” (victorious war). Its increasingly aggressive anti-Semitism was a result of several changes in imperial German wartime politics. These included the establishment of the Independent Social Democratic Party in April 1917, the reform announcement by the emperor (“Easter Decree”), the Peace Resolution of the majority parties in the Reichstag from July 1917 (the SPD, the Center Party, and the left-liberal Freisinn), and the failure of the right-wing Sammlungsbewegung (collective movement) of the German Fatherland Party, which was founded in September 1917. The Pan-German League invested heavily in the acquisition of new papers such as “Deutschlands Erneuerung” and the “Deutsche Zeitung”, which both became leading voices for Pan-German propaganda. As the Burgfrieden increasingly eroded and the German Fatherland Party failed to mobilize mass support for a victorious peace, the league’s most powerful ideological asset, the mobilization of anti-Semitism, now became an essential element in explaining Germany’s political fragmentation. Jews were blamed for undermining the unity of wartime German society. Finally, in 1917, Claß spoke of two conflicting ideologies competing with each other: “Pan-Germanism” and “Pan-Judaism”. Fear of losing several moderate members of the league by introducing anti-Semitism as official politics resulted in the postponement of the executive committee’s decision to implement a “Jewish Committee”, which became effective in September 1918. Early versions of the anti-Semitic “stab-in-the-back legend” were distributed by Claß shortly after the war.

The Legacy of Pan-German Activism after the First World War↑

Pan-German demands for territorial expansion on the European continent and in the colonial peripheries remained core elements in the programs of the “old” radical right from imperial Germany and “new” movements such as the National Socialist German Workers’ Party, which included similar demands in its twenty-five-point program of 1920. After the breakdown of the multi-ethnic Habsburg Empire in 1918, the Pan-Germans were at the forefront of the “Anschluss” movement both in Germany and Austria, where the Pan-German League founded its Austrian branch organization (1919-1935). The Pan-German League facilitated the success of the most important anti-Semitic association after the war, the German Völkisch Protection League (1919-1922/23). Ethnic homogenization of German society, racism, and Social Darwinism remained features of the völkisch movement and the radical right after 1918, and were further radicalized by the Pan-German League.

After Pan-German attempts to overthrow the Weimar Republic by a putsch between 1919 and 1923 failed, the league increasingly focussed their activism on the German National People’s Party (1919-1933), to help the founding member of the Pan-German League, Alfred Hugenberg (1864-1951), become chairman of the party. This was successful on 20 October 1928, and a broad coalition of the “national opposition” was formed to overthrow the republic by legal means. These efforts and the illusion of using and taming Adolf Hitler (1889-1945) encouraged Hugenberg to form a coalition with Hitler on 30 January 1933.

Björn Hofmeister, Freie Universität Berlin

Section Editor: Mark Jones

Selected Bibliography

- Barth, Boris: Dolchstoßlegenden und politische Desintegration. Das Trauma der deutschen Niederlage im Ersten Weltkrieg 1914-1933, Düsseldorf 2003: Droste.

- Chickering, Roger: We men who feel most German. A cultural study of the Pan-German League, 1886-1914, Boston 1984: Allen & Unwin.

- Fischer, Fritz: Griff nach der Weltmacht. Die Kriegszielpolitik des kaiserlichen Deutschland, 1914-1918 (2 ed.), Düsseldorf 1967: Droste.

- Geiss, Imanuel: Der polnische Grenzstreifen, 1914-1918. Ein Beitrag zur deutschen Kriegszielpolitik im Ersten Weltkrieg, Lübeck 1960: Matthiesen.

- Hofmeister, Björn: Between monarchy and dictatorship. Radical nationalism and social mobilization of the Pan-German League, 1914-1939, Washington, D.C. 2012: Georgetown University.

- Leicht, Johannes: Heinrich Claß 1868-1953. Die politische Biographie eines Alldeutschen, Paderborn 2012: Schöningh.

- Lohalm, Uwe: Völkischer Radikalismus. Die Geschichte des Deutschvölkischen Schutz- und Trutz-Bundes, 1919-1923, Hamburg 1970: Leibniz.