A Sense of Duty↑

William Orpen (1878-1931), portraitist and subject painter, was born in Blackrock, county Dublin in 1878. He showed prodigious artistic talent from childhood and entered the Dublin Metropolitan School of Art (DMSA) at the age of twelve in 1891. He progressed to the Slade School of Art, London, in 1897, and subsequently became a leading painter of the New English Art Club. Orpen maintained close connections with Ireland and taught at the DMCA where he influenced numerous younger Irish artists. He was interested in the Irish nationalist movement and Irish cultural life and supported the efforts of Hugh Lane (1875-1915) to establish a gallery of modern art in Dublin.

When Great Britain entered the First World War, in August 1914, Orpen was known as one of the most sought-after society and political portraitists of his generation. The war quickly impacted his career, however, and commissions became less frequent, were cancelled or left unpaid. The early events of the war occurred at a relative distance to Orpen, however, on 15 November 1914, Avenal St George (1894-1914), the son of his beloved patron, Evelyn St George (1870-1936), was killed in action at Zillebeke in Belgium.

Orpen suffered a further loss when Hugh Lane died with the sinking of the British liner Lusitania by a German U-boat on 7 May 1915. That year, Sean Keating (1889-1977), Orpen’s studio assistant at the time, encouraged him to consider returning to Ireland. Orpen was sympathetic to the British war effort and told Keating, “I’ll do what I can ... I won’t fight anybody or kill anybody but I’ll do something.”[1] Orpen declared his availability to enlist under the Derby Scheme in December 1915. He was commissioned into the Army Service Corps as second lieutenant and stationed at Kensington Barracks.

Official War Artist↑

A wide public interest in pictures of the war and exhibitions of paintings by artist soldiers led to the establishment of the British war artist scheme in May 1916. Muirhead Bone (1876-1953) was appointed Britain’s first official war artist. The Daily Mirror announced Orpen’s appointment as an official war artist by Sir Douglas Haig (1861-1928) on 30 January 1917.

Orpen was promoted to the rank of major and arrived in France on 8 April (Easter Sunday) 1917. He spent much of the next two years in France, far longer than any other British war artist. Orpen’s rank and personal connections ensured that he experienced a relatively comfortable lifestyle as a war artist. He was afforded a personal car and driver; he employed a batman and assistant at his own expense; and he enjoyed an unusual freedom of movement and access to senior military personnel.

Unlike other war artists who had served in the army, Orpen never experienced or witnessed combat first hand. He worked instead behind the frontline and produced a large body of paintings and drawings representing different aspects of military and civilian life as well as more subjective reflections on the effects of war. This included portraits of senior ranking officers, generals, infantry soldiers and other service people; scenes of everyday life in the towns and villages along the Western Front; allegorical images; representations of shellshock; and depictions of war-torn landscapes in the aftermath of notable battles.

An Onlooker in France↑

In his memoir, An Onlooker in France (1921), Orpen documented his life as a war artist, from his first arrival in Boulogne in 1917 to his commission to paint the Paris Peace Conference in 1919. Along with his regular letters to both his wife Grace Orpen (1878-1948) and Evelyn St George, his book is a major source in understanding his personal experience of the war.

Orpen arrived in France with a degree of excitement and enthusiasm and wrote to Grace, “what a wonderful day I have had – it really is all to [sic] wonderful beyond my highest expectations.”[2] He was frustrated quickly by army protocol and promptly informed his colonel in Rollancourt that his accommodation at Hesdin “was too far away from anything near the front” and he intended to go to Amiens immediately.

From Amiens, Orpen made his first visit to the Somme battlefields, some five months after the battle had ended. He wrote later that, “I shall never forget my first sight of the Somme … there was this endless waste of mud, holes and water … miles and miles of it, horrible and terrible, but with a noble dignity of its own.”[3] Orpen’s fascination with the Somme manifested itself in a series of views of the battlefield, made through the spring and summer of 1917. There is a notable absence of human activity in these pictures, which instead contemplate the terror of the conflict through the remnants and traces of battle that were left on the landscape, in its aftermath.

Orpen painted military portraits throughout his time in France. He was intrigued, in particular, with the fighter pilots of the air corps. During a sitting with Douglas Haig, the field marshal told him, “why waste your time painting me, go and paint the men, they’re the fellows who are saving the world and they are getting killed everyday.”[4] In June and July Orpen visited Cassel and the Ypres Salient. He visited the support and reserve trenches, and made individual studies of soldiers waiting to advance or returning from the front line. He also sketched German prisoners.

Aftermath↑

In late 1917, Orpen became seriously ill and required hospitalisation. In spring 1918, he was recalled to London to explain his painting of Yvonne Aubicq (1896-1973), a woman with whom he had developed an intimate relationship, and whose portrait he had given the controversial title of “A Spy”. A large collection (125) of Orpen's war paintings and drawings were displayed at Agnew's Gallery in London in May 1918. This included a selection of self-portraits of Orpen as a war artist, as well as a number of theatrical subject pictures. The latter, such as “The Old Woman of Douai”, reflect Orpen’s interest in pictorial allegory, as a device to express different psychological meanings and moral perspectives on the war.

Orpen donated the majority of his war art to the British government. These are now in the collection of the Imperial War Museum (IWM). Orpen was appointed knight commander of the Order of the British Empire in June 1918. He returned to France in July and continued to paint portraits, more views of the Somme, and scenes set in the aftermath of other battles, notably at Zonnebeke.

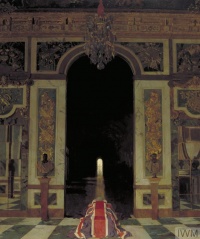

After the war, the IWM commissioned Orpen to paint proceedings at the Paris Peace Conference, which commenced in January 1919. Orpen made numerous studies towards two major group portraits: “A Peace Conference at the Quai d’Orsay” set in the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the “The Signing of Peace in the Hall of Mirrors” set at the peace conference in Versailles. Orpen worked on a third painting “To the Unknown British Soldier in France” in remembrance of the British soldiers who had lost their lives in combat. The painting was the subject of public controversy due to Orpen’s choice of imagery. The IWM declined to accept it until he removed portraits and nude military figures from the composition in 1927.

Orpen’s experience of the war affected him deeply. Although his celebrity as a war artist brought him greater fortune and fame, he never recovered from both the physical and mental trauma of the experience. His health deteriorated over the subsequent decade until his death in 1931, at the age of fifty-two.

Donal Maguire, Curator, ESB Centre for the Study of Irish Art, National Gallery of Ireland

Section Editor: Jennifer Wellington

Notes

- ↑ Keating, Sean: William Orpen. A Tribute, in: Ireland Today 2 (1937), p. 5.

- ↑ National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin, ESB Centre for the Study of Irish Art, William Orpen Archive, Orpen, William to Grace Orpen, April 1917, IE NGI/IA/ORP1/5/1/1/7/6/1.

- ↑ Orpen, William: An Onlooker in France, London 1921, p. 18.

- ↑ Ibid, p. 28.

Selected Bibliography

- Arnold, Bruce: Orpen. Mirror to an age, London 1981: Cape.

- Orpen, William, Upstone, Robert / Weight, Angela (eds.): William Orpen. An onlooker in France. A critical edition of the artist's war memoirs, London 2008: Paul Holberton Publishing.

- Upstone, Robert: William Orpen. Politics sex and death, London 2005: Philip Wilson.

- William Orpen Archive, ESB Centre for the Study of Irish Art, National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin