Life before World War I↑

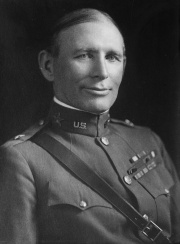

As a young man, Dennis E. Nolan (1872-1956), the son of Irish immigrants, seemed headed to Cornell University and a career as a teacher, but a chance opening diverted him to the United States Military Academy at West Point. There he was an excellent student as well as a baseball and football player. He graduated in 1896 and was commissioned as a lieutenant of the infantry.

Nolan earned two Silver Stars and served as a brigade acting assistant adjutant general in Cuba during the Spanish-American War. He was assigned to the Philippines in 1899 as a temporary major and commanded a cavalry squadron. In 1901 he returned to West Point to teach law and history. Two years later, he joined the intelligence section of the newly-formed War Department General Staff. When this assignment ended, he returned to the Philippines and served for a time under John J. Pershing (1860-1948). Service in Alaska with the 30th Infantry Regiment followed, before Nolan returned to the General Staff in 1915 and the following year earned a promotion to major. At the behest of the Army chief of staff, Hugh Scott (1853-1934), Nolan worked conscription. These efforts were crowned with success in May 1917, when Congress passed the Selective Service Act.

World War I↑

When the United States entered World War I in April 1917, Pershing was named commander of the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF). He selected Nolan to be his assistant chief of staff, G-2 or chief intelligence officer.

By American standards Nolan had significant intelligence experience and had served with several officers who pioneered the country’s development of military intelligence. However, he had no preconceived notions about how to organize the AEF’s intelligence work, and initially he was the only member of the G-2. In his consultations with the British and French, he fended off suggestions that the AEF leave this sensitive work to the Allies. Instead, after studying the Allies’ intelligence systems, Nolan decided that the AEF should primarily imitate the British system. Nevertheless, both British and French instructors taught American intelligence personnel, and many of the AEF’s field manuals and pamphlets on intelligence topics were translations of French publications.

Under Nolan, the AEF G-2 eventually numbered approximately 300 carefully selected personnel. Nolan divided the G-2 division into four sections. G-2A, which Nolan thought the most important, was responsible for intelligence analysis and most intelligence collection - notably, signals intelligence. G-2A’s remit ranged from technical military questions to estimating the French coal supply in order to determine whether a shortage of coal might force France to sue for peace in 1917. G-2B was responsible for espionage and counterespionage, but Nolan found it to be only a “minor part” of G-2’s work. G-2C did topography and mapmaking, and G-2D was in charge of censorship, press affairs, and propaganda.

Nolan also was responsible for counterintelligence and operational security. He disseminated guidance on operational security and counterintelligence to all troops. To this end, he also asked the War Department’s Military Intelligence Division in Washington to send him fifty French-speaking sergeants with investigative experience to form the Corps of Intelligence Police.

Though Nolan was never part of Pershing’s inner circle, Pershing thought highly of him and oversaw his promotions up to his post as temporary brigadier general in August 1918. Nolan was one of the few officers allowed immediate access to Pershing whenever he desired it; he also briefed Pershing every morning. During the Meuse-Argonne Offensive in September 1918, Pershing gave Nolan temporary command of the 55th Brigade. Nolan won the Distinguished Service Cross for his service in that position.

Post-war Life↑

After the Armistice of 11 November 1918, Nolan was assigned to support the American delegation at the peace conference, where he helped draft the German disarmament agreement. He returned to the United States in July 1919 and taught intelligence at the Army War College until he became the War Department’s director of military intelligence. He held this position from September 1920 to August 1921, during which time he was made a permanent brigadier general. As director, he reorganized the Military Intelligence Division and coped with a sharp decline in the Division’s manpower and budget. He managed to somewhat soften the impact of these cuts by arguing successfully for the creation of a military intelligence component within the Army Reserve, a move that eventually paved the way for the recognition of Military Intelligence as its own branch within the U.S. Army in 1962. Nolan also insisted on the retention of the Corps of Intelligence Police, a group that, renamed the Counter Intelligence Corps, would persist well into the Cold War as an important counterintelligence and espionage organization.

After leaving the intelligence world, a series of command and staff positions followed for Nolan, culminating in assignments as deputy chief of staff of the Army and a Corps Area commander. Nolan retired in 1936 as a major general.

Mark Stout, Johns Hopkins University

Section Editor: Lon Strauss

Selected Bibliography

- Cooke, James J.: Pershing and his generals. Command and staff in the AEF, Westport 1997: Praeger.

- Kovach, Karen, U.S. Army Intelligence and Security Command (ed.): The life and times of MG Dennis E. Nolan, 1872-1956. The army's first G2, Fort Belvoir, Va. 1998: U.S. Army Intelligence and Security Command, History Office.