Introduction↑

At the roots of the Mexican Revolution were two fundamental contradictions produced by the process of modernization during the reign of Porfirio Díaz (1830-1915) from 1876 to 1910/11. In the economic sphere, the upper classes and foreign investors benefitted from export-led development while peasants and rural workers suffered its regressive effects. In the political sphere, the autocratic Porfirian rule ossified the political system and excluded the majority of the population from political participation. When Díaz was re-elected for the seventh time as president in a fraudulent poll, it was the opposition candidate Francisco I. Madero (1873-1913) who led an insurrection that marked the beginning of the revolution in November 1910. The elected government of Madero, which came to power following the fall of Díaz in May 1911, disagreed from the start with the political forces that aimed at far-reaching social and economic transformations in Mexico, most notably, substantial land reforms.

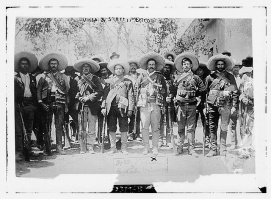

Madero was overthrown in February 1913 by a conservative coup led by General Victoriano Huerta (1850-1916). While Huerta’s government remained internationally isolated, within Mexico only the northern states Coahuila and Sonora refused to recognize Huerta. From these states a military campaign was initiated against his regime, which was joined by forces led by Francisco “Pancho” Villa (1878-1923) in Chihuahua. Villa was a former outlaw, small businessman and colonel in the insurrection of 1910. After a civil war, between March 1913 and July 1914, these so-called “constitutionalist” forces, together with Emiliano Zapata's (1879-1919) army, removed Huerta from power. Going forward, the revolutionary process developed in various entanglements with the First World War.

Civil War (1914–1917)↑

In a new civil war between the constitucionalistas under Venustiano Carranza (1859-1920) – who took over government affairs in August 1914 – and his general, Álvaro Obregón (1880-1928), and the convencionistas led by Villa and Zapata, the United States first supported Villa. When Villa suffered military defeats between April and July 1915, U.S. diplomats began to work towards a settlement between the revolutionary leaders. The strategy failed, and at the same time, the United States gave up their original plan to neutralise Carranza by military force. Secretary of State Robert Lansing (1864-1928) considered the involvement of the U.S. army in Mexico as an unwelcome strengthening of Germany’s position. On the contrary, Woodrow Wilson (1856-1924) finally recognized Carranza’s government in October 1915 and supplied the regime with weapons, in part because he considered the United States to be freer to participate in the world war after having stabilised the situation in its “backyard”.

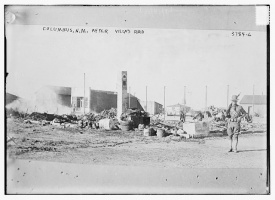

On 9 March 1916, Villa responded with an attack on the border village of Columbus, New Mexico, with 200 men intended to provoke a U.S. military intervention in Mexico. The only foreign military attack on United States’ territory in the 20th century lasted three hours; seventeen Americans died and more than 100 villistas were killed. Ultimately, however, Villa’s strategy paid off. Wilson sent an expeditionary force of more than 7,000 men under General John J. Pershing (1860-1948) into Mexico. After the campaign, Pershing was Wilson’s first choice for the appointment of Commander-in-Chief of the American Expeditionary Forces in the war in Europe. U.S. troops remained in Mexico until February 1917, without being able to capture Villa. Instead, the intervention provoked a surge of Mexican nationalism. However, the U.S. intervention was not a complete failure in that the U.S. army gained valuable military experiences – particularly with respect to the large-scale use of motor transport, the organization of medical services, and the use of aviation – which turned out to be of considerable importance for the United States’ entry into the war in Europe.

After having reduced Villa’s military power decisively, the constitutionalistas headed south in April 1916 to combat the zapatistas in the state of Morelos. In a violent campaign, 30,000 Constitutionalist soldiers defeated the Zapatista army within a few weeks. The “revolution within the revolution”, which the zapatistas had initiated in 1914 and which had entailed the most far-reaching land reform of the whole revolutionary process, then came to a halt.

Carranza’s Foreign Policy and German, British, and U.S. Policies towards Mexico (1917–1918)↑

The idea to provoke a war between Mexico and the United States played a prominent role in the plans of the German government to complicate a U.S. intervention in Europe and to hinder the export of American arms. At the beginning of 1915, the Germans promised arms and money to ex-president Huerta if he would wage a war against the United States in the case that he would return to power. The conspiracy was discovered by the United States.

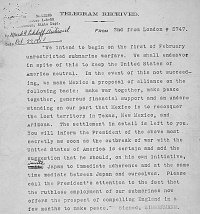

With the Pershing expedition, Carranza’s search for a countervailing force intensified. In November 1916, he proposed to the German minister of foreign affairs, Arthur Zimmermann (1864-1940), an overt cooperation between the two governments. In January 1917, Zimmermann proposed on his part an alliance with Carranza that would come into force if, and when, the United States entered the war. His offer of “substantial financial support and consent on our part for Mexico to reconquer lost territory in Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona”[1] was intercepted by British intelligence and forwarded to U.S. authorities. The so-called “Zimmermann telegram” became an effective tool in the hands of the advocates of a U.S. declaration of war, and significantly influenced Wilson’s decision to enter the conflict. For Carranza, Zimmermann’s offer was no option.

In March 1917, Carranza was elected president. His willingness to maintain the country’s neutrality found its expression in February 1917 through his efforts to form a bloc of neutral nations. In the same month, a new constitution was adopted and made the Mexican nation the owner not only of the whole land within the state’s boundaries, but also the natural resources beneath the surface of the territory. With these legal foundations for an agrarian reform and a nationalization of the oil industry, British and U.S. companies saw their interests in Mexico as threatened. The relations between the British and Carranza began to deteriorate. While British business interests soon preferred the political strategy of coming to terms with the Mexican government, British military leaders and politicians continued to perceive Carranza as a revolutionary who was about to make common cause with Germany and, therefore, had to be destabilized. The U.S. policy towards Mexico developed in the opposite direction. While companies campaigned for an overthrow of Carranza’s government, the Wilson administration’s priority was to keep Mexico “quiet” and to avoid intervention because it was thought that the United States should concentrate their military forces in Europe. This notwithstanding, the U.S. government tried to exert economic pressure on Mexico in order to push the government to revoke the revolutionary constitution. This strategy was not successful.

A crucial issue in the strategic considerations of all actors involved in the international interplay with and around the Mexican Revolution was oil. While the U.S. administration feared the expropriation of U.S. owned oil companies, Carranza could never completely exclude the possibility of a U.S. occupation of oil fields on Mexican territory. Carranza’s increase of the taxes on petroleum in 1918 caused the most heated conflict between Mexico and United States after the latter’s entry into the war. Oil supplies from Mexico were also of great importance for the British fleet. The Germans also focused on the oil fields in Mexico; first when they planned sabotage operations to provoke a war between Mexico and the United States and later in their efforts for an economic expansion in Mexico.

German policy in Mexico – similar to the British – met with little success, due to analytical incompetence coupled with an overestimation of its own possibilities of influence. The United States’ policy was successful at least in some aspects, such as the avoidance of a broader military intervention in the country, the safeguarding of the interests of U.S. companies in Mexico and the control of German secret services. Carranza, in turn, was able to maintain Mexico’s neutrality as well as achieve the withdrawal of U.S. troops from Mexico. Carranza also managed to get the Germans to abstain from sabotage activities on Mexican territory against their enemies. Much more conservative in his social than in his foreign policy, he was swept away by a military rebellion in 1920, which he had triggered himself by detaining his former general - and now political opponent - Álvaro Obregón. With the election of Obregón as the new president that same year, the era of the civil wars in Mexico came to an end.

The “Slackers” and the Social Revolution↑

When the United States adopted universal, male military conscription, thousands of war resisters escaped to Mexico. While the majority of the probably 30,000[2] so-called “slackers” only sought to avoid the alternative between the army and the prison, a few dozen, who had participated in radical left-wing activities, got involved in the Mexican Revolution. They were inspired by their internationalist creed and their identification with the cause of profound social transformation.

The “slackers” found protection under Carranza’s government and provincial governors, and received financial support, opportunities to publish, and direct access to influential political leaders. Some of them played an important role in the radical currents of the Mexican Revolution. For Mexican socialism, they played an important role as bridge-builders with the U.S. radical left and international socialist debates. In 1919, the “slackers” participated in the foundation of the Partido Comunista Mexicano (PCM) and became crucial for bringing revolutionary leftists in Mexico in contact with the project of the emerging Communist International .

Stephan Scheuzger, Universität Bern

Section Editor: Frederik Schulze

Notes

- ↑ Quoted after Boghardt, Thomas: The Zimmermann Telegram. Intelligence, Diplomacy, and America’s Entry into World War I, Annapolis 2012, pp. 66–67.

- ↑ La Botz, Dan: American ‘Slackers’ in the Mexican Revolution. International Proletarian Politics in the Midst of a National Revolution, in: The Americas 62/4 (2006), p. 563.

Selected Bibliography

- Gilderhus, Mark T.: Diplomacy and revolution. U.S.-Mexican relations under Wilson and Carranza, Tucson 1977: University of Arizona Press.

- Katz, Friedrich: The secret war in Mexico. Europe, the United States, and the Mexican Revolution, Chicago 1981: University of Chicago Press.

- Katz, Friedrich: The life and times of Pancho Villa, Stanford 1998: Stanford University Press.

- Knight, Alan: The Mexican Revolution. Porfirians, liberals and peasants, volume 1, Lincoln 1990: University of Nebraska Press.

- Knight, Alan: The Mexican Revolution. Counter-revolution and reconstruction, volume 2, Lincoln 1990: University of Nebraska Press.

- La Botz, Dan: American 'slackers' in the Mexican Revolution. International proletarian politics in the midst of a national revolution, in: The Americas 62/4, 2006, pp. 563-590.

- Meyer, Lorenzo: México y los Estados Unidos en el conflicto petrolero, 1917-1942 (2 ed.), Mexico City 1972: Colegio de México.

- Silva Herzog, Jesús: Breve historia de la revolución mexicana, 2 volumes, Mexico City 1960: Fondo de Cultura Económica.

- Smith, Robert Freeman: The United States and revolutionary nationalism in Mexico, 1916-1932, Chicago 1972: University of Chicago Press.

- Tobler, Hans Werner: Die mexikanische Revolution. Gesellschaftlicher Wandel und politischer Umbruch, 1876-1940, Frankfurt a. M. 1984: Suhrkamp.

- Womack, John: Zapata and the Mexican Revolution, New York 1970: Vintage Books.