Early Life↑

Margaretha Geertruida Zelle (1876-1917) was born on 7 August 1876 in the northern Dutch town of Leeuwarden. She was the daughter of Adam Zelle (1840-1910), who ran a prosperous business in caps. Her parents spoiled the beautiful little girl, who always had her way. However, when she was thirteen, her father went bankrupt. She was put into the care of her godfather but found it hard to follow her new family’s stuffy rules. She saw only one solution: to get married. Margaretha answered a notice from Rudolf MacLeod (1856-1928), a thirty-eight-year-old major in Dutch East India. They married shortly thereafter and embarked for the island of Java. Once there, Margaretha began dressing like the native women, spent recklessly and soon became a popular subject of local gossip.

Breaking from Tradition↑

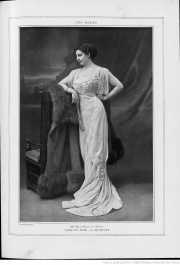

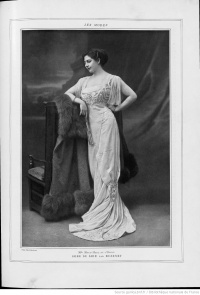

In 1900 MacLeod retired and the family returned to Amsterdam. Margaretha divorced him on grounds of adultery and maltreatment. Aged twenty-six, she was now free and traveled to Paris, albeit without money. She checked into the Grand Hotel under an enigmatic new name, Mata Hari. The first name was formed using the first and last syllable of her Christian name; the second was a Javanese term symbolizing the sun or “the day’s eye.” The East was fashionable at the time and in spite of her lack of technique, her Javanese dances fascinated everyone. Her amber-colored skin, long black hair, and beautiful, supple body were powerful assets. Emile Guimet (1836-1918), founder of the Museum of Asian Art, vouched for her, saying that all the Parisian salons wanted her, although it was unclear if it was the ritual that fascinated them or the boldness of a “strip tease” that had not yet been named. Her rates soared and her list of lovers grew longer every day. However, as the years went by, she received fewer and fewer contracts.

From Dancer to Spy↑

In January 1914 Mata Hari made the most of her charms and secured a contract in Berlin, which was cancelled in August. She then had to borrow money to survive and soon returned to Holland. The German consul general in The Hague, an intermediary of the German Intelligence Service, offered Hari a large sum of money to go on an intelligence mission in France. She accepted and became agent H21. Elsbeth Schragmüller (1887-1940), the Fräulein Doktor responsible for the French Department of the German Secret Service Office in Antwerp (Belgium), taught Hari the art of spying. But she soon mistrusted the abilities of her pupil who considered spying a game and thought that being a secret agent simply entailed a succession of fabulous visions. Confident of her ability to manipulate her German, then French military employers just as she had manipulated her lovers, Hari ignored politics, was too talkative and always urgently needed money. In September 1916, Captain Georges Ladoux (1875-1933), chief of the French Secret Service, suggested she become a double agent. She agreed and traveled to Spain via Great Britain, where she was constantly watched over. She never took even minimum precautions when sending information, which generally proved to be of little interest or out of date. Consequently, in January 1917, Captain Ladoux refused to pay her. She wrote him: “I am ready to do all what you want….I am an international woman, don’t dispute the way I am working!” He never replied.

A Tragic End↑

Hari, this foreign cosmopolitan, emancipated, venal courtesan, was arrested in February 1917. Her trial began at a time when the political and military contexts were difficult in France because of internal political scandals and the difficult military situation, including the defeat at Chemin des Dames. Sentenced to death after a fake trial, she was executed on 15 October 1917 in Vincennes. “However there was nothing to make a fuss about,” André Mornet (1870-1960), the attorney responsible for the court martial, later argued.

Mata Hari was the impresario of her own life, an imaginary life which fascinated her surroundings and in which she was imprisoned. She invented mysterious origins: sometimes born in India as a natural daughter of the Prince of Wales and an Indian princess, sometimes born in Java. Greta Garbo (1905-1990) personified her beautifully in her characteristic unsteadiness in the best film about her, which came out in 1931.

Marianne Walle, Rouen University

Section Editor: Emmanuel Debruyne