Introduction↑

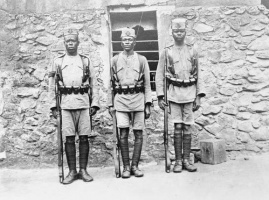

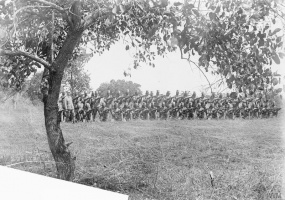

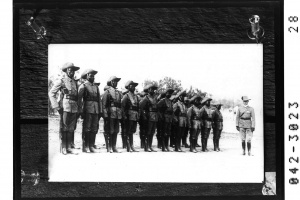

Since African involvement in the First World War was extensive, Africans had to make sense of their war experiences even if the war appeared to many as a European affair. East Africa offers a particularly fruitful area for examining the ways Africans made sense of the war, since fighting there began in August 1914 and ended only in November 1918, two weeks after the Armistice in Europe. As perhaps in no other African theatre of the war, the fighting affected the lives of Africans and the fabric of their societies. Hundreds of thousands of Africans served as soldiers and porters, and saw their lands become battlegrounds for the warring European nations. In contrast with other battlefields in Africa, mainly Africans fought on the battlefields. From the beginning, German and Belgian troops included East Africans, and the British also eventually relied on recruits from the region. The war, moreover, had major consequences for colonial rule. In many parts of Eastern Africa, the security deteriorated dramatically, and so did colonial control of local societies. The war effort strained the ability of the colonial state to intervene in local societies.

Nonetheless, European colonial rule survived without major damage, even if after the war former German colonies came under the mandate system of the League of Nations. There was no Wilsonian moment in Africa. It took another world war before African nationalists could move forward with their demands for an end of European colonial rule on the continent.[1] However, not all was that quiet on the African front. Africans expressed their discomfort with the war and colonial rule in many ways. Waves of strikes and upheavals shook Northern Rhodesia in 1914 and Nyasaland in 1918. The Gold Coast and Nigeria experienced a series of riots between 1914-1918.[2] There were also demonstrations of support by African elites for British war aims in most of the British colonies. In the end, there was no one African perspective on the war. In contrast to Europeans, though, the perspectives and memories of Africans (as well as other non-Europeans, such as Indians) about the war have been almost invisible to the historian. In the 1970s, historians such as Melvin Page, Lewis Greenstein, and Geoffrey Hodges conducted extensive research into the oral memories of the veterans who fought for the British.[3] However, other scholars have not continued or extended this work to other participants in the war. This article picks up the thread and offers new approaches to understanding the perspectives of Africans on the war, taking East Africa as a particularly fruitful example of the sorts of reactions that may have animated African responses in other areas of the continent.

The War in Eastern Africa↑

The war in Eastern Africa began some days after the hostilities started in Europe, increasing dramatically in intensity and scale from 1916. Although mobile warfare dominated, there were also periods of trench warfare. Whereas the campaigns in Southwest-Africa and Cameroon were fought in the desert or in the inaccessible part of the rain forest, in Eastern Africa much of the fighting took place in highly populated regions of the central plateau and in the north-western part of the colony. Fighting in Unyamwezi, for example, raged with particular intensity in 1916 and 1917. In the second half of 1916, Belgian troops occupied the region after heavy fighting with German forces, and in spring of 1917 the fighting returned when the Germans broke through the Belgian front-lines and tried to reach Lake Victoria. This culminated in one of the most brutal episodes of the war, when German and Belgian troops both committed numerous atrocities against the civilian population. Whole villages were abducted and plundered by passing troops. Due to the prolonged period of fighting and the disruption of daily life it caused, several regions in East Africa saw episodes of famine between 1916 and 1918.[4]

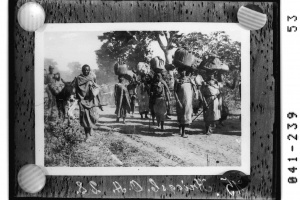

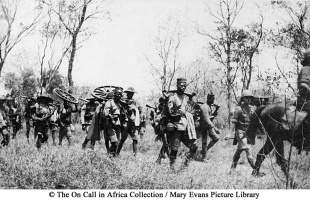

Even where there was no fighting, the war affected the lives of Africans. Hundreds of thousands of Africans literally kept the war economy running. According to an official estimate by the Colonial Office, British forces alone engaged between 500,000 and 750,000 porters during the campaign, while German sources indicate up to one million porters in the service of the British. The Belgians recruited nearly 260,000 porters. The number who served the Germans is less clear, but historian John Iliffe estimates that, in 1916, at the time of their highest troop strength, the Germans employed no more than 45,000 porters in their service.[5] Porters were essential to the war effort on all sides. The ratio of porters to officers among the German troops was between four and six to one. Belgian officers were served by up to eighteen porters. Soldiers usually had up to three porters.[6]

To be recruited or, as it happened in many cases, abducted to serve as a porter was therefore the most common experience for Africans in the war. Military labor was in many regards embedded in colonial patterns. As in the prewar years, African chiefs played a major part in recruitment. Porterage was nothing new to many young male Africans. It was indeed one of the main occupations in the colonial economy. Yet the war saw a dramatic increase in the numbers involved. The war was, therefore, for many Africans most obviously connected to a new level of colonial intervention in their daily lives. They often reacted with open or passive resistance. One of the major rebellions during the war, the Chilembwe uprising of 1915, was connected to demands by the British administration for military labor and rising prices for food.[7]

Experiences of the War↑

The colonial administrations’ efforts to recruit Africans for the war were increasingly hampered by rumors of the harsh and deadly conditions faced by carriers and soldiers. The rumors were hardly exaggerations. More than 13,000 soldiers and 100,000 to 300,000 carriers died during the war, most of them from hunger, exhaustion, and diseases.[8] Poor preparation, devastated lands, and lengthening supply routes brought on hunger as a daily companion of soldiers and carriers. Carriers also lacked suitable clothes and tents to protect them from bad weather. If they were wounded or ill, they often failed to get medical treatment in the far away and overcrowded hospitals.[9] Carriers had to bear loads of up to 50 or 60 pounds, moving on roads and paths that turned into mud with rain or became dusty and unbearably hot in dry weather. Many tried to desert. The desertion rate among Belgian carriers was as high as 20 percent, and not much lower among British carriers.[10]

Although only few askari or carriers died in combat, modern technologies of killing affected their psyches. When the British used armored cars and war planes for the first time in 1916, German askari fled in panic. Artillery fire left soldiers cruelly mutilated and its impact on the psyche of Africans was comparable to shell-shock trauma experienced by soldiers on the Western Front. The thunder of German guns, the carrier Amini bin Saidi remembered, made him deaf for weeks, and he suffered from insomnia because of his constant fear of death. The carrier Marius Karatu deserted after he saw the bodies of his comrades killed and mutilated by shelling.[11] Another veteran of the war remembered the high casualties inflicted by the guns and compared the war with the armed conflicts before the arrival of Europeans: never before had so many people died in a war.[12] A song performed after the war by dancers at Lake Tanganyika recalled the horror of these days:

Bring cannons for a terrible war. Let’s return to the coast, we brave soldiers,

We have beaten the Mitamba savages.[13]Traumatic experiences prevented veterans from speaking about the events even decades after the war had finished. For most of them the war and its horrors made little sense. It was a war of Europeans for reasons to be found in Europe.[14]

For most of the population in the war zones, raids for porters, and increasingly for food and war booty, too, became a common occurrence as the war dragged on. Troops were poorly disciplined, and the price was paid by Africans. In many cases, raids were accompanied by atrocities like the rape, murder and mutilation of women, and execution of Africans who resisted the troops pillaging their villages and abducting their people.[15]

In a chaotic situation punctuated by the atrocities of highly mobile, marauding troops, deserters, and the forces of local strongmen, escape was often the only choice left to civilians. In some regions, they only returned years after the war. Some Africans, nevertheless, responded with open resistance, notably when small parties of soldiers came to plunder. Belgian patrols at Lake Tanganyika were attacked by villagers, either murdered or disarmed, and sent back to their officers. Some chiefs tried to negotiate with Belgian officers. King Musinga (1883-1944) of Rwanda wrote several letters to the Belgian Commander in Chief Charles Tombeur (1867-1947) to protest the behavior of Belgian troops. A chief near Lake Victoria told Tombeur that Europeans could fight in Europe rather than in Africa if they had problems with each another. Clearly, one way Africans made sense of the war was by seeing it as an essentially alien affair, a matter for Europeans and unfairly visited upon Africans.

Perspectives and Memories of the War↑

In local histories, the war was sometimes compared to the events connected to the inter-regional caravan trade of the 19th century, when the struggle over caravan routes and the hunt for slaves caused civil war, destruction, and the displacement of many Africans. African soldiers serving the Belgians, who often came from the western shores of Lake Tanganyika, were accused of being cannibals, an accusation that had its origins in the 19th century. A song from Usukuma describes the horrors connected to the arrival of Belgian troops in the region:

The Germans and the English. The God of the Europeans alone knows, What business of cattle is theirs. But our God will bring back our men. Dig, O bin Makoma, trenches in Tabora. Others will arrive, the Belgians,

Who eat men.[16]Many Africans soldiers serving the Belgians were Manyema from the western shores of Lake Tanganyika. They had played a major role in the slave raids of the 19th century. Since these days accusations of cannibalism served as a marker for atrocities committed by warriors serving slave traders and, later, soldiers serving the Europeans. The Belgians and the British often regarded themselves as liberators of Africans from the yoke of German colonial rule. This was a view hardly shared by many Africans. Instead, they became attracted to prophecies of the end of colonial rule. A common theme of these prophecies was of the war as a cleansing storm, in which aberrations from “traditional” norms and behavior caused by the contact with Europeans and experience of colonial rule would be revoked. At Lake Victoria, the first days of the war saw the emergence of a new cult, whose preachers prophesied the end of British rule:

Preachers of the Watchtower Church, who had played an important part in the Chilembwe uprising of 1915, saw in the war an omen of the end of colonial rule and the coming of Armageddon. Those who were not baptized would face death, and the whites would either become slaves or be expelled from the land. When German troops crossed the region between Lake Nyassa and Lake Tanganyika many followers of the Church saw this as a fulfillment of these prophecies. Other religious movements also used millenarian prophecies to mobilize their followers. The Ndochbiri rebellion in the Kigezi District of Uganda was driven by interpretations of the war as a sign of the coming end of the world.[18] Many of these religious movements were highly syncretistic and resonated well after the war. In 1922, a British administrator learned that prophecies of the coming end of the world spread among the Muslim population of Liwali. A certain Shaykh Ahmad, supposedly a guardian at the tomb of Mohammad in Medina, was told by the prophet that the end of the world was coming soon, preceded by the decline of the power of Europeans. Heaven would turn into hell and the demon of a new Christ would arise.[19]

In some regards, Islam was a main beneficiary of the war. The number of Muslims in East Africa grew in substantial numbers, from 3 percent of the population in prewar years to 25 percent after the war.[20] Sufism, with a strong tradition of millenarian beliefs, gained many followers. A major reason for this was the decline of European missions during the war. Many mission stations were deserted either because the missionaries were deported as enemy nationals, or because they left with troops from their home countries. Moreover, the Germans had declared the war a jihad against the British and Belgians and persecuted and humiliated British and French missionaries and African converts.[21] For many Africans, Christianity lost much of its appeal as the embodiment of progress and power, replaced by the askari, who were mostly Muslim. The war was in many regards a continuation of the opening of horizons that John Iliffe has described: a closer connectedness of East Africans with the wider world that began with the inter-regional caravan trade.[22]

Perhaps one of the most popular means to reflect on the war were the Beni dance societies. They had their origins in the coastal culture of the 19th century. Then, the rich patricians of Lamu and Mombasa sponsored elaborate feasts in which rival dance groups competed. Shortly before the war, Beni dance had spread to German East Africa, but its most rapid dissemination occurred after 1914. Beni dances became a popular pastime for soldiers and carriers serving German and British troops. Returning home, the soldiers and carriers introduced the dances into their societies.[23] A detailed description of Beni dances at Lake Tanganyika by an African missionary teacher reveals how the war was experienced by the people in the region. The dances mimicked violence of the marauding soldiers, and the brutal treatment of porters with the kiboko, the lash. The dancers portrayed the idiosyncratic rules of European war, such as the taking of prisoners. Songs recalled the rape of women by British askari:

She cried on marrying in Zanzibar. Listen men of Mkanda I first conceived because of a soldier of the 7th K.A.R.

That soldier came and deflowered me in Zanzibar.[24]When the dance competitions were over, the victorious party gained the right to have sex with the women of the losing team.

For the British colonial officials, who, beginning in 1917, tried to establish a colonial administration in the former German territories, the Beni dances and the millenarian movements were an expression of a crisis of colonial rule. Africans no longer sought answers for the problems of their societies from Europeans. Though they were not political or anti-British movements, one officer argued, Beni dances and Sufi orders weakened ethnic identities and made contacts between different groups easier. This posed a grave danger to colonial rule, because it provided a basis for religious and political movements like “Pan-Islamism” and “Äthiopianismus”.[25] The war, indeed, weakened ethnic identities. Many Africans had become refugees or had been forced to serve as soldiers or carriers. Urban centres like Daressalam became melting pots, mixing peoples from around East Africa and even West and South Africa. One of the major goals of British policy was to reverse these developments. In November 1918, the British forced more than 4,000 former askari and carriers to leave Daressalam for their home villages. The deported responded with protests, in which Beni dance societies played an important role.[26]

Conclusion↑

The First World War had serious and widespread effects on Africa, forcing Africans to try to make sense of their experiences, their involvement in a global war of empires, and their future in the colonial world. Millions died during the war and the influenza pandemic that followed it; millions more had been mobilized to work and fight, and economies were disrupted across the continent. Social unrest in some areas heralded the stirrings of African nationalism.[27] The First World War, in fact, resulted in the first major crisis of Europe’s overseas empires. Inspired by Woodrow Wilson’s (1856-1924) criticism of colonialism, Asian and Arab nationalists intensified their struggle for independence and, in the case of Egypt, eventually achieved it.[28] The League of Nations mandatory rule over former German colonies provided anti-colonial activists and national politicians from the colonial world a global arena to voice their critique of colonialism for the first time. There was also a widespread perception among colonial officials, particularly the British, of the war as a moment of crisis.[29]

Nonetheless, the war itself was, in fact, a climax of colonial rule. The war economy led to an increased bureaucratization of the colonial state, more investments in infrastructure, and greater access to the African workforce. Even African production was on the rise in many areas. Despite the heavy price Africans had to pay for the European war, the political situation remained generally calm. The few uprisings were suppressed within a short time.[30] While German East Africa became a mandate territory called Tanganyika, little changed as the British and Belgians replaced the Germans as colonial rulers. It was merely a change of clothes, as one historian put it. Most East Africans responded to the change of colonial rulers with disinterest.[31]

Yet the war did change many Africans’ perspective on colonial rule. Europe as a model for the future of African societies was challenged, at least for some years after the war, by a spread of local prophetic beliefs, Islam, and African churches. In British East Africa, the first associations to advocate African interests were founded in the mid-1920s; Tanganyika followed in the 1930s. These were the first tentative steps in the history of African nationalism in the region, as Africans themselves made sense of the war as an opportunity to imagine a different political future.

Though this article has focused on East Africa, a comparison with West Africa shows the different regional paths political movements took in the aftermath of the war. A major difference between West and East Africa was the entanglement of the former within the wider world of the Black Atlantic, which stimulated the emergence of stronger nationalist movements. In 1914, for example, the Jamaican Marcus Garvey (1887-1940) founded the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA). After his immigration to the United States, the UNIA became a powerful movement aimed at the improvement and representation of Afro-Americans and Africans and linking with, and in some ways transforming, the powerful transatlantic Pan-African movement. By the early 1920s, the UNIA was a powerful anticolonial voice irritating French and British colonial officials, who feared its effects on nationalist aspirations in West Africa.[32]

Making sense of the First World War for Africans involved the opening of horizons and greater entanglement with political movements around the globe during and after the war. These responses were just as much a part of the process of interpreting the war’s meaning and consequences as millenarian religious movements and dance societies. Whether in East Africa or elsewhere on the continent, Africans confronted new realities that they had to integrate into their understandings and actions, since the war was as inescapable reality for them as it was for Europeans.

Michael Pesek, Universität Hamburg

Section Editors: Melvin E. Page; Richard Fogarty

Notes

- ↑ Dumbuya, Peter A.: Tanganyika under International Mandate, 1919-1946. Lanham 1996; Digre, Brian Kenneth: Imperialism's New Clothes. The Repartition of Tropical Africa, 1914-1919, New York 1990.

- ↑ Yoshikuni, Tsuneo: Strike action and self-help associations: Zimbabwean worker protest and culture after World War I, in: Journal of Southern African Studies 15/3 (1989); Killingray, David: Repercussions of World War I in the Gold Coast. In: The Journal of African History 19/1 (1978); Osuntokun, Akinjide: Disaffection and Revolts in Nigeria during the First World War, 1914-1918. In: Canadian Journal of African Studies 5/2 (1971).

- ↑ Greenstein, Lewis J.: Africans in a European War. the First World War in East Africa with special reference to the Nandi of Kenya, Ann Arbor 1977; Hodges, Geoffrey: The Carrier Corps. Military Labor in the East African Campaign 1914-1918, London 1986; Page, Melvin E.: The war of Thangata. Nyassaland and the East African Campaign, 1914-1918, in: Journal of African History 19/1 (1978).

- ↑ Pesek, Michael: Das Ende eines Kolonialreiches. Ostafrika im Ersten Weltkrieg, Frankfurt 2010.

- ↑ Schnee, Heinrich: Deutsch-Ostafrika im Weltkriege - wie wir lebten und kämpften. Leipzig 1919, p. 126; Iliffe, John: A Modern History of Tanganyika. Cambridge 1979, p. 249.

- ↑ Archives of the Force Publique at the Foreign Ministry of Belgium, henceforth FP 2659/1155 Compte rendu des opérations établi par le Capitaine Commandante Jacques, n.d.

- ↑ Rotberg, Robert I.: Chilembwe’s Revolt Reconsidered, in: Rotberg, Robert I. and Mazuri, Ali A. (eds.): Protest and Power in Black Africa. New York 1971; Yorke, Edmund: The Spectre of a Second Chilembwe. Government, Missions, and Social Control in Wartime Northern Rhodesia, 1914–18, in: The Journal of African History 31/3 (1990); Higginson, J.: Liberating the Captives. Independent Watchtower as an Avatar of Colonial Revolt in Southern Africa and Katanga, 1908-1941, in: Journal of Social History 26 (1992); Page, Melvin E.: The war of Thangata 1978 and The Chiwaya War. Malawians and the First World War, Boulder, CO 2000.

- ↑ Iliffe, Modern History, p. 246.

- ↑ Rodhain: Rapport sur le functionnement général du services médical des troupes de l’est pendant la campagne 1917, 24.11.1918, FP 2261 /1170; Rapport sur le Fonctionnement général du service médical des troupes de l’est pendant la campagne 1914-1916, FP 2661/1172; Rapport sur le fonctionnement du service médicale. n.d., FP 2661/1170; Paice, Edward: World War I. The African Front, New York 2008, p. 393.

- ↑ Le Gouverneur Général à Monsieur le Ministre des Colonies, 1916, FP 814; Instructions a observer en ce qui concerne le transport des porteurs militaires lèves suivant ordonnance du 4 juillet 1917, FP 2666/1231; Hodges, Carrier Corps 1986, pp. 101.

- ↑ Amini bin Saidi, The Story of Amini bin Saidi of the Yao Tribe of Nyasaland, in: Margery Freda Perham (eds.): Ten Africans, London 1963, p. 145; Hodges, The Carrier Corps 1986, p. 53.

- ↑ Hodges, Carrier Corps 1986, p. 63.

- ↑ The Beni Society of Tanganyika Territory, in: Primitive Man 11/1/2 (1938): p. 79.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 70, 170-81; Greenstein, Lewis J.: The Nandi experience in the First World War. In: Page, Melvin E. (ed.): Africa and the First World War. New York 1987, p. 82.

- ↑ For war crimes during the campaign see, Pesek, Das Ende eines Kolonialreiches 2010, pp. 242.

- ↑ Koritschoner, Hans: Some East African Native Songs, in: Tanganyika Notes and Records 4 (1937): p. 61.

- ↑ Wipper, Audrey: The Gusii Rebels, in: Rotberg and Mazuri, Protest and Power in Black Africa 1970, p. 390.

- ↑ Gray, Richard: Christianity. In: Roberts, Andrew (ed.): The Colonial Factor in Africa. Cambridge 1990, p. 173; Fields, Karen: Revival and Rebellion in Colonial Central Africa. Princeton 1985, p. 324; His Majesty's Stationery Office (HMSO) (ed.): Report on Tanganyika Territory for the Year 1921. London 1922, p. 22; NA WO 106/259 District Commissioner’s office, Kabale, to The Provincial Commissioner, Western Province, Kigezi District, 26.6.1919

- ↑ Bagshave, F. J. E.: Personal Diaries, Bagshave, F. J. E. Papers. Oxford n.d., p. 21.2.1922.

- ↑ Nimtz, August H.: Islam and politics in East Africa. The Sufi order in Tanzania, Minneapolis 1980, p. 77.

- ↑ For a detailed description see: Pesek, Michael: Sulayman b. Nasir al-Lamki and German colonial policies towards Muslim communities in German East Africa, in: Bierschenk, Thomas and Stauth, Georg (eds.): Islam in Africa. Münster 2002; Pesek, Das Ende eines Kolonialreiches 2010.

- ↑ See, Ranger, Terence O.: Dance and Society in Eastern Africa, 1890-1970: The Beni -Ngoma, London 1975; Pouwels, Randall Lee: Horn and Crescent. Cultural Change and Traditional Islam on the East African Coast, 800-1900, Cambridge 1987.

- ↑ For a history of the Beni see, Ranger, Dance and society in Eastern Africa 1975.

- ↑ The Beni Society of Tanganyika Territory, p. 79.

- ↑ Muggeridge Report, Nairobi, 29.7.1919, NA WO 106/259.

- ↑ Ranger, Dance and society in Eastern Africa 1975, p. 91; Burton, Andrew: African underclass. urbanisation, crime & colonial order in Dar es Salaam, London 2005, p. 63.

- ↑ Henderson, Ian: The Origins of Nationalism in East and Central Africa. The Zambian Case, in: The Journal of African History 11/3 (2009), pp. 591-603; Page, Melvin E.: The Great War and Chewa Society in Malawi. In: Journal of Southern African Studies 6 (1980), pp. 171-82.

- ↑ Manela, Erez: The Wilsonian Moment. Self-Determination and the International Origins of Anticolonial Nationalism, Oxford 2007.

- ↑ NA WO 106/259 Memorandum Africa for the Africans and Pan-Islam. Recent Developments in Central and Eastern Africa by Captain J.E. Philipps; NA WO 106/259 British Policy in Africa Notes on a conversation which took place on June 29th, 1917.

- ↑ See, Dumbuya, Peter A.: Tanganyika under International Mandate, 1919-1946. Lanham 1996. Digre, Imperialism's New Clothes 1990. Iliffe, A Modern History of Tanganyika 1979.

- ↑ See, Pesek, Das Ende eines Kolonialreiches 2010.

- ↑ Cronon, Edmund David: Black Moses. The Story of Marcus Garvey and the Universal Negro Improvement Association, Madison 2007.

Selected Bibliography

- Anonymous: The Beni Society of Tanganyika Territory, in: Primitive Man 11/3/4, 1938, pp. 74-81, doi:10.2307/3316216.

- Fields, Karen E.: Revival and rebellion in colonial central Africa, Princeton 1985: Princeton University Press.

- Greenstein, Lewis J.: Africans in a European war. The First World War in East Africa with special reference to the Nandi of Kenya, Ann Arbor 1975: University Microfilms International.

- Hodges, Geoffrey: The Carrier Corps. Military labor in the East African campaign, 1914-1918, New York 1986: Greenwood Press.

- Iliffe, John: A modern history of Tanganyika, Cambridge 1979: Cambridge University Press.

- Mazrui, Ali A. / Rotberg, Robert I. (eds.): Protest and power in black Africa, New York 1970: Oxford University Press.

- Nimtz, August H.: Islam and politics in East Africa. The Sufi order in Tanzania, Minneapolis 1980: University of Minnesota Press.

- Pesek, Michael: Das Ende eines Kolonialreiches. Ostafrika im Ersten Weltkrieg, Frankfurt a. M. 2010: Campus.

- Ranger, Terence: Dance and society in Eastern Africa, 1890-1970. The Beni Ngoma, Berkeley 1975: University of California Press.