A New Belgian Government↑

In October 1918, Albert I, King of the Belgians (1875–1934) established his headquarters at Loppem Castle near Bruges. From 11 to 14 November, he received visits from various eminent figures in occupied Belgium, including the Socialist Edouard Anseele (1856–1938) and the Liberal Paul-Emile Janson (1872–1944). King Albert also met Emile Francqui (1863–1935), a businessman who led the National Aid and Food Committee. At the end of the war, Francqui became a very influential person, not only in the economic but also in the political field. These persons informed the King, in particular, of the severe difficulties facing the country: German revolutionary movements, social demands, and pillaging, among others.

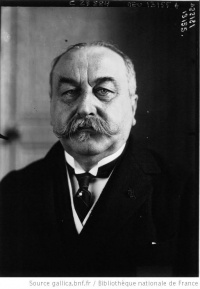

Meanwhile, the tripartite government, led by the Catholic Gérard Cooreman (1852–1926), was gathered in Bruges. Considered a "transitional government," its position was uncertain. On 13 November, Cooreman tendered the resignation of his Cabinet to the King. His colleagues were shocked; they had not been consulted. The next day, King Albert asked Léon Delacroix (1867–1929), a Catholic lawyer who had not been very politically active previously, to constitute a new, tripartite Cabinet. Delacroix had been suggested by Francqui because he was a moderate "new man" and seemed able to lead important political reforms.

Development of a new political program required discussion of several issues, such as trade union recognition and the use of Dutch in Ghent University. However, the key measure in this new political direction was the immediate granting of universal suffrage to men aged twenty-one and above. Before the war, the Catholic politician Charles de Broqueville (1860-1940) had been willing to consider changing the voting rules, as called for by the Socialists and Liberals. However, the traditionalist Catholic right-wing had opposed universal suffrage. Now, universal suffrage seemed essential to shore up the morale of a population marked by four years of occupation. Theoretically, however, this measure could only be adopted by revising the Constitution: a long procedure. By appointing Delacroix, who favored the immediate implementation of universal suffrage, Albert I prioritized urgent change over respect for the Constitution.

On 21 November, the new government was formed. Léon Delacroix was appointed prime minister. This title was used for the first time in Belgian history, indeed the prime minister's role had increasing importance on the political scene. While the Catholics held an absolute majority within Parliament, the new executive branch comprised six Catholics, three Liberals, and three Socialists. This was a turning point: the end of the long-standing Catholic domination of politics. Henceforth, Catholics would have to share power with left-leaning parties. These meetings and actions based at Loppem, then, marked the definitive inclusion of the Belgian Workers Party in the regime.

Reaction↑

The traditional Catholic right was unhappy to have been sidelined from the Loppem discussions and condemned the way in which the new government was formed. It regretted the move to universal suffrage, but also the fact that voting rights had not been extended to women, who, it felt, would be more favorable to its cause. These politicians also denounced the procedure as unconstitutional. Finally, the role of the king was questioned – was he personally in favor of the Loppem decisions or was he unduly pressured by the Socialists? For all these reasons, the rumour of coup d’Etat – and the expression “Coup de Loppem” – appeared.

King Albert finally intervened in the discussions. On 10 February 1930, he sent a letter to his prime minister, which was published the following day in the press. Albert insisted that the Loppem decisions had been made entirely freely, not under the threat of any sort of revolution. His explanation seems convincing; even before the end of the war, for example, he personally supported universal suffrage. Moreover, he was not in favor of the long Catholic hegemony and preferred a tripartite government. The Loppem discussions had merely reinforced his convictions: it was time for big change.

Vincent Delcorps, Catholic University of Louvain

Section Editor: Emmanuel Debruyne

Selected Bibliography

- Haag, Henri: Le choix du roi Albert à Loppem, in: Albert, Colloque Roi / Wyffels, Carlos (eds.): Actes du Colloque Roi Albert, Brussels 1976: Archives Générales du Royaume, pp. 169-191.

- Haag, Henri: Le témoignage du Roi Albert sur Loppem (février 1930), in: Bulletin de la Commission royale d'histoire 141, 1975, pp. 312-347.

- Velaers, Jan: Albert I. Koning in tijden van oorlog en crisis, 1909-1934 (Albert I. King in times of war and crisis, 1909-1934), Tielt 2009: Lannoo.